Little by little, the art market is undergoing a constitutional shift. Economic and political headwinds, as well as changing generational tastes, are challenging even the pinnacle of the trade, leading mega-galleries and global auction houses to rethink their businesses.

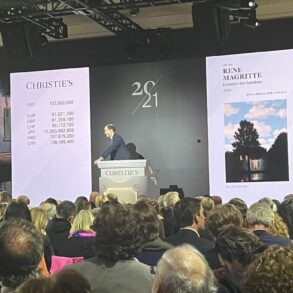

The latest data clarifies the urgency. Last year, dealers with turnover of more than $10m saw their average sales decline by 7% (compared with a 19% increase in 2022), according to the latest Art Basel & UBS Art Market Report. Sotheby’s reported in August that its core earnings were down 88% in the first half of 2024. Over the same period, aggregate global auction sales at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips dropped 27%, per July findings from the analysts at ArtTactic.

Anecdotally, however, the picture is more complex, with the many loosely related sub-markets that make up “the art market” reacting differently as operational costs spike and sales fluctuate.

Cutting back to size up

Some of the biggest commercial galleries and auction houses are restructuring their operations and workforces to protect their bottom lines while simultaneously expanding in other ways.

Sotheby’s, which is owned by the highly leveraged billionaire Patrick Drahi, was still consulting over making around 50 redundancies in London amid reports in the Wall Street Journal that it has stalled payments to its art shippers and conservators by as much as six months. All this as the auction house spent tens of millions renovating new luxury and retail spaces in Paris and Hong Kong (where sales have been postponed from September to November).

Other high-profile departures from top galleries—including Gagosian severing ties with chief operating officer Andrew Fabricant and Laura Paulson, a director of its in-house advisory service—appear to be less about cost-cutting than about subtle strategic shifts.

White Cube has undergone “a number of changes internally” over the past year, says Sam Johnson, who was appointed chief executive in November 2023 at “a critical time of growth” for the London-headquartered gallery. Johnson, a former investment banker, was previously a managing partner at the art advisory Beaumont Nathan, which specialises in blue-chip secondary market works.

“The business has almost doubled in size in five years, with new galleries in New York, Seoul and Paris, as well as more online and secondary market activity,” Johnson says. Since 2018, the dealership has taken on eight artists’ estates to meet the growing demand for tried-and-tested work.

But White Cube has made cuts elsewhere. Among the biggest changes this summer was replacing all 38 invigilators in London—most of them artists and students—with security guards. Johnson points out that 13 former invigilators are continuing casual work with the gallery and five have been given fixed-term or permanent contracts in different roles.

All of the auction houses are pushing back on covering extra expenses

Multiple ex-invigilators say they were told by White Cube staff that their termination “follows a general trend across similar galleries that are moving away from visitor engagement to visitor management”. The layoffs, the former employees say, will make White Cube less welcoming to the public and more a place where “art is increasingly made, sold, seen and bought by only a privileged few”.

Johnson says this “policy decision” was “not about expense, nor about visitor figures or a lack of engagement”. He adds: “After assessing the business needs in London, we decided it was important to work with specially trained contractors who are better placed to both protect the art and, on very rare occasions, our staff.” Despite personnel cuts during the pandemic, Johnson says that over the past five years “the workforce on permanent and fixed-term contracts has grown by over 60%”.

Reduced opening hours

After reassessing its own visitor engagement efforts, Hauser & Wirth recently cut the public opening hours at its Bruton, Somerset gallery from six hours a day, six days a week to five hours a day, four days a week. Tuesdays and Wednesdays have become dedicated to “school, university and group visits” as part of an expansion “of our commitment to our learning activities”, a gallery spokesperson says.

Though students take priority, groups can also include museum patrons, curators and collectors. “It’s about the flow of people in the gallery and the experience of, say, a group of 20 people and individual visitors—having dedicated days helps,” the spokesperson says. The gallery declined to say if the schedule change has affected any jobs.

Over the past few years, Hauser & Wirth has invested in its publishing, scholarship and education programmes, launching its Education Lab initiative in 2021 with a project in downtown Los Angeles spearheaded by the artist Mark Bradford. Other labs are based in Somerset and the gallery’s €4m centre on Menorca’s Illa del Rei. The latter, which opened in 2021 and hosts artist residencies, is another evolution by Hauser & Wirth in an increasingly competitive market—and, crucially, one that keeps its biggest-earning artists happy.

Other galleries are re-evaluating their digital offerings, having invested in online viewing rooms and other such platforms during the pandemic. According to the online publication Observer, David Zwirner recently restructured its digital team, leading to a 3% cut of the gallery’s full workforce. A spokesperson declined to comment on specific figures, saying: “The reorganisation of the gallery’s digital team was due to the completion and implementation of a custom-built database, and the successful replatforming of the gallery’s website.”

Pace Gallery, too, has selectively scaled back, including via two recent departures from Pace Verso, its web3 arm. The Art Newspaper understands these were a response to artists’ waning interest in blockchain projects. Three senior directors also left the gallery over the summer.

Yet Pace has followed these noteworthy cuts with major hires, some to round out its recent investments in Asia. Evelyn Lin, a veteran of Christie’s and Sotheby’s, took up her role as Pace’s president of Greater China on 1 October to oversee regional sales, business development and artist-engagement efforts. The gallery has taken on nine new staff in Japan, led by Kyoko Hattori, who left her role at Phillips to run Pace’s new Tokyo space. The gallery also added two curatorial and artist-management positions, including a curatorial directorship in New York for the art historian Xin Wang, reflecting a gallery-wide reprioritisation away from brand partnerships towards scholarly exhibitions.

Do the houses always win?

Auction houses are facing a steeper challenge, even as Christie’s—unlike Sotheby’s—has so far managed to avoid redundancy consultations.

Nonetheless, significant drops in auction sales across the board present a problem for every house. The Italian art lawyer Massimo Sterpi says the drastic fee structure makeover at Sotheby’s, implemented last May, “is clear evidence of a crisis”. The new scheme reduces buyers’ premiums across price tiers in favour of shifting more costs onto sellers—a move the New York-based art adviser Nilani Trent thinks could backfire.

“All of the auction houses are pushing back on covering extra expenses—even on private sales—such as shipping, which is a standard cost covered by a gallery when a work is consigned,” she says. “This offers an opportunity for galleries to regain control of their artists’ secondary markets, which have been aggressively controlled by auction houses and speculators for the past decade.”

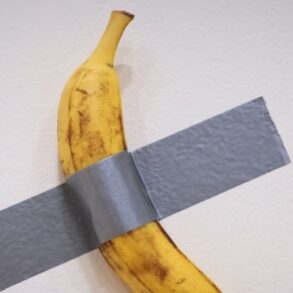

Amid this policy shift, the luxury market has become a growing focus not only for Sotheby’s but also for high-end galleries, which have been offering more artist-licenced merchandise and other retail goods every year (see p. 49). But the top sellers are not alone in pursuing this adjacent revenue stream.

This month Chabi Nouri arrives as Bonhams’s new chief executive; she comes from a luxury retail background, most recently as the chief executive of the jeweller Piaget. According to chairman Hans-Kristian Hoejsgaard, Bonhams has “designated luxury as a clear growth opportunity”, though 20th- and 21st-century art, Chinese works of art, jewellery and cars remain the business’s pillars.

The firm is undergoing another “significant shift” operationally, as online sales rose from contributing 35% of its overall auction revenue to 60% in the first half of 2024, resulting in a “few redundancies”, Hoejsgaard says. Yet Bonhams also announced in September that it will upgrade its New York headquarters by moving to Steinway Hall, a landmarked building with 30% more square footage than its current home. (The price of the space was undisclosed.)

With one eye on profit margins, trimming fat is a common strategy for businesses in a challenging climate. But in a distinctly depressed art market, creative strategy and adaptability have become key even for the most blue-chip of enterprises. And the resulting modifications—whether small or large, public-facing or behind the scenes—have the potential to reshape the entire art trade.