Alphonse Mucha was one of the central figures in the Art Nouveau movement. While our world of AI-generated images and hyper-efficient processes may feel far removed from Mucha’s life in Paris at the turn of the century, there is plenty that today’s creative can learn from the artist.

Jackie Dunn, senior curator at The Art Gallery of NSW, spoke with B&T about the spectacular “Alphonse Mucha: Spirit of Art Nouveau” exhibition on show until 22 September. A major theme in the exhibition is Mucha’s advertising prowess — and there are plenty of gold nuggets that marketers can pick up on today.

Mucha is famous for having created the first celebrity endorsement, featuring actress Sarah Bernhardt and the first global campaign.

While print ads had been around for 20 years before Mucha was active, “nothing really existed in the way that Mucha’s poster work was done. Nothing predated that,” said Dunn.

“For that reason alone, you’re talking about an origin point of advertising and consumer culture as it was exploding in Paris at the time”.

Paris at the turn of the century was experiencing an explosion of consumer culture, led by the availability of mass-produced products, artworks, and other goods.

All these products had to reach consumer bases and get sold somehow, and Mucha was a key figure in this. “He helped to build the language of early consumer culture,” said Dunn.

Celebrity Endorsements & Global Campaigns

Mucha was one of the first artists to work in both celebrity and corporate branding. His poster for Lu cookies featuring actress Sarah Bernhardt was the first celebrity endorsement in an ad.

Bernhardt and Mucha’s relationship was marked by collaboration, and the popularity of the posters built a brand for Bernhardt as well as the artist.

“His posters of Bernhardt became so popular that it didn’t matter what theatrical production they were advertising, people were interested in her. She is at the centre of the poster, and it’s really her that you’re coming to see,” said Dunn.

“It’s hard now to conceive of the power Bernhardt had. Today we have lots of extraordinary celebrities, but when you’ve only got one or two, they kind of dominate the cultural climate. So Bernhardt was immediately swamped with work. What I love is that he takes as much care with every commissioned ad as he did with his early work,” added Dunn.

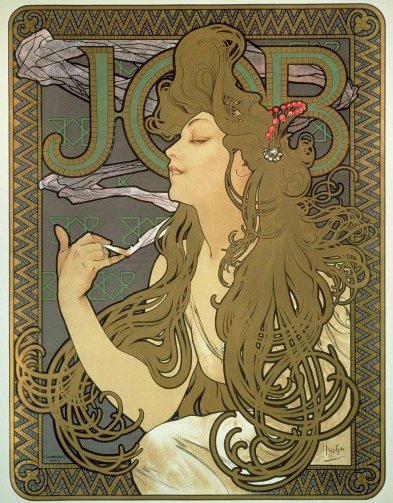

He also created advertisements for Moet and Chandon and JOB, a cigarette company.

Mucha painted “Russia Must Recover,” the earliest example of a global campaign.

“This is one of the most successful global campaigns, even today, let alone at the time, that has ever been undertaken. It aimed to raise funds for the dreadful famine in Russia. It was an international, global campaign much like Band-Aid campaigns. America was very behind it, trying to raise funds,” said Dunn.

“In a poster like this, Mucha is using his advertising and communication techniques and has really honed them into this image, which is quite moving”.

Art should serve a purpose, even advertising

“Mucha didn’t really believe in art for art’s sake, he believed that art should serve a purpose, whether that purpose is selling cigarette papers or the liberation of your country,” said Dunn. “You might feel more passionately about the liberation of your country, but they both serve a purpose and that was important to him”.

At the same time, the products in Mucha’s posters aren’t forced onto the viewer. His posters are playful and subtle, with elements completely unrelated to the product. The style and atmosphere trumped product information and text, allowing the image to speak for itself.

His images created an identifiable aura that came to be associated with Mucha rather than an isolated product. Thus, consumers were buying into a lifestyle rather than a product. This style became known as the ‘Mucha Style’.

“He became so famous that he was kind of allowed to do anything. There was no advertising agency saying you can’t do that or this. He had all this freedom. He brought a Slav decorative element in, stars and Byzantine tiles”.

This subtle form of advertising “predated so much of advertising that came later on that is suggestive and subtle”.

Shifting the Dial

On how advertising has changed since Mucha’s time, Dunn felt that social awareness was the driving element.

“I think advertising today is more cautious about what its social impact is. There’s a lot of backlash if there’s an advertisement that’s created that is not considering the impact of its content”.

“I’m so glad that media studies today teach us about how to be vigilant when an industry is so utterly all-consuming.

“There’s been a big shift in the last 40 years or so about slick advertising that didn’t give a hoot about its impact on the world to something much better, more aware”.

Is Marketing An Art?

Much like the conversations we see in today’s climate regarding what constitutes a work of art, there was heated debate about whether marketing should be considered art even in Mucha’s time.

“Mucha struggled with judgment from other artists around him, who said he was nothing more than a decorative artist”.

“So many artists of the Art Nouveau generation were determined to have art in everything, in everyday life. Yet other artists in the academy would have thought Mucha was just a decorative artist. There’s still that battle between art and advertising and it doesn’t start breaking down in the West until the 80s and 90s”.

But Mucha didn’t want to be pigeonholed — “he didn’t want to be just a decorative artist,” said Dunn.

“I think modern adverts can exist on gallery walls. I don’t know if it’s for us to judge, I guess it’s more about what are the ones that break-through. Some artists bring an artist’s vision to an ad. It’s not so much whether it’s good enough to be in an art gallery, it’s more a question of, whether it’s created by somebody who thinks like an artist, who approaches the topic and the content like an artist, in which case they do tend to stand out and leave a legacy”.

“Creativity is what binds them together,” she added.

Perhaps the next time you’re working on a campaign put aside the mouse and keyboard and consider the palette and the brush. Maybe one day you’ll also end up in a museum.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content