When we think about spreading knowledge of Central Asian art in Europe, we might think of exhibitions, of festivals, of panels and talks, not necessarily of an art fair. However, in the contemporary art world, it is today the market, more than art critics, which dictates the emergence of certain art scenes as a whole.

For the historically underrepresented Central Asian art market, smaller fairs represent today an important alley, more than the big fairs such as Art Basel – which just had its second Paris iteration this October. Smaller “boutique fairs,” as they are called, often present curated programming which allow a wide public – not just collectors and buyers – to enjoy the art as it was an exhibition. A selling one, of course.

In Paris, the most relevant fair which has historically presented Central Asian artists to the European public is called Asia Now, and it took place in Paris from October 17 to 20. Entirely dedicated to Asian art, the fair has historically tried to fill the gap for Central Asian art in the European market in the past ten years of its existence.

The fair has selected more than 70 leading and emerging contemporary art galleries from all over the world, presenting more than 220 artists coming from 26 territories from all over Asia and its diaspora, stretching from Central Asia to the Asia-Pacific, including West, South, South-East, and East Asia.

Their commitment to expanding knowledge of Central Asian art in Europe culminated last year in a show which was indeed focused on Central Asia, and curated by the artist group Slav and Tatars.

While seminal Central Asian galleries such as the Aspan Gallery from Almaty and Pygmalion Gallery from Astana didn’t return to Asia Now this year, the fair still presented a number of Central Asian artists and practices, interspersed between the main show, and the booths.

Central Asian Artists in the Radicant’s Main Show

The main exhibition of Asia Now was curated by Radicants, a collective founded by art critic Nicolas Bourriaud, and it was centered on sacred ceremonies seen as a powerful tool for re-examining societal structures and reconnecting with ancestral roots.

Called “Ceremony,” the main show was co-curated by Nicolas Bourriaud and Alexander Burenkov, a curator of Russian origins who has been working for a long time with Central Asian narratives, which are also featured prominently in the show.

Image: TCA, Naima Morelli

The idea of ceremony ties to the tenth anniversary of the art fair, but at the same time the curators opted to explore the nuances of ritual as both a “celebration of ancestral wisdom” and a “critical tool for interrogating and redefining established traditions and power dynamics.”

As Burenkov noted, the decision to use the theme of ceremony emerged after conversations with Asia Now director Alexandra Fain. “The choice fell on ‘ceremony’ in all its variability and polysemy [was used] to explore the non-obvious meanings of ritual through the eyes of contemporary artists as well as philosophy, science, and poetry which inspire them,” Burenkov stated.

In selecting the 18 artists for the exhibition, Bourriaud and Burenkov brought together both well-known and emerging figures. Their aim was to “put together established and well-known artists with artists completely unknown to the French art scene.” This fusion underscored the show’s mission to amplify often overlooked voices from Asia and Central Asia and to offer new perspectives to a European audience. Through these artists, the curators sought to dispel a simplistic, almost consumeristic notions of celebration, presenting instead an exploration of how rituals shape and transform cultural identity.

Ariuna Bulutova’s Shamanic Rituals

One of the show’s most impactful Central Asian voices is Ariuna Bulutova, a Buryat artist who draws from indigenous practices to explore human relationships with the natural world.

“Bulutova’s work is deeply rooted in ‘Lusuud,’ a Buryat shamanic ritual, which she integrates into a video installation guided by her parents, who are practicing shamans,” explained the curator. Bulutova’s art interweaves ancestral knowledge with climate awareness, creating a platform where traditional Indigenous wisdom connects with modern ecological issues. Her work serves as an urgent call for renewed respect for the environment, a quest to heal our relationship with the world beyond the human.

Presenting the show at La Monnaie was challenging, yet inspired the selection of participatory works. “Since the building is a historical monument, nothing can be attached to the walls,” Burenkov noted, explaining the need to create a unique setup that prioritized performative pieces.

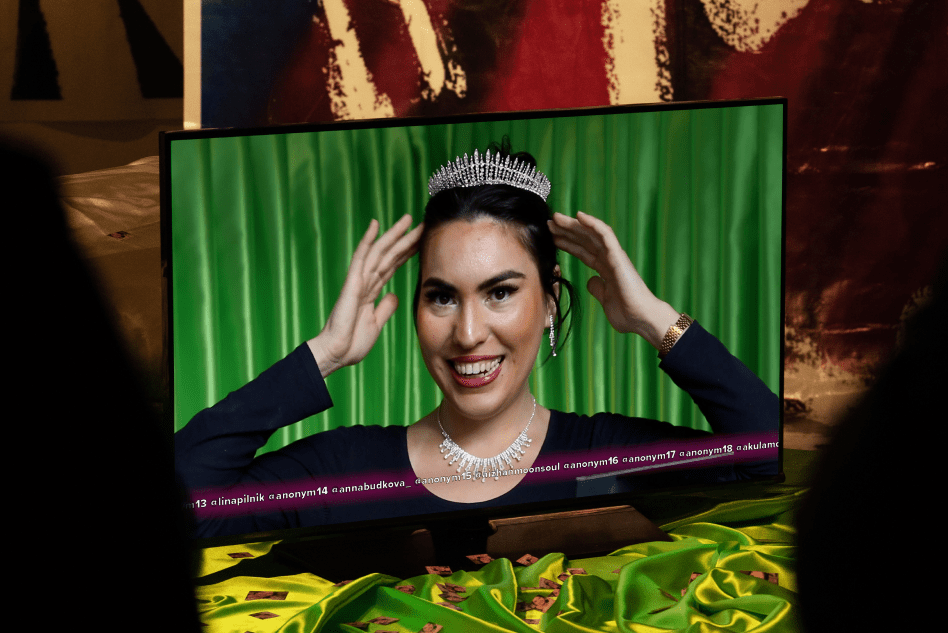

Another Central Asian artist in the show, who presented a striking video piece called “Don’t Miss the POV”, was Uzbek artist Faina Yonusova. Living between Uzbekistan and Germany, Yonusova navigates the complexities of her cultural background, seeking to create artistic representations that resonate with depth and authenticity, while embracing the fluidity of contemporary existence.

Artwork by Faina Yunusova; image: TCA, Naimi Morelli

In her artistic practice, Yunusova focuses on self-reflection and societal inquiry, exploring themes of memory and communal expectations in the digital age. She is also engaged in postcolonial studies within Central Asia, with a focus on the hybridity and fluidity of cultural identity and self-exoticization. Her expansive portfolio spans monumental painting, photography, video, digital art, artificial intelligence, performance, and installations.

While curating a ritual-focused show within a commercial fair context might be challenging, Burenkov saw it as an opportunity to disrupt market-driven expectations. Performances like Darius Dolatyari-Dolatdoust’s “Flags Parade” invited visitors to engage with questions of identity and belonging, questioning “whether we are local or migrant, European or Asian.” The artist’s work, which involved costumes symbolizing a blend of Iranian, French, Polish, and German heritage, “queers the traditional model of the art fair” and promotes unexpected, transformative encounters.

Reflecting on the role of art fairs as rituals, Burenkov likened curating to “cooking out the show”— a process with its own rhythm and traditions that requires both careful planning and improvisation.

Gulnur Mukazhanova’s Explorations of Kazakh Craft

Walking between the different booths of the fair, one of the most fascinating installations that jumps out was the work of Gulnur Mukazhanova in the booth of Michael Janssen.

One of the most interesting names on the scene, Mukazhanova’s canvases – made of felt, a material carrying a strong significance – engage deeply with Kazakh cultural heritage and the complexities of post-Soviet identity.

Artwork by Gulnur Mukazhanova; image: TCA, Naima Morelli

While presented in a commercial context, these works are highly touching and aesthetic encounters, and present a depth which situate them not just as objects for sale, but also meaningful explorations of themes such as nationalism, gender, and inherited trauma.

The artist is employing the traditional Kazakh medium of felt in new and powerful ways. While felt historically holds a central role in Kazakh craft as a material for everyday life, Mukazhanova transforms it into symbolic canvasses through which she addresses hidden wounds and the unconscious impacts of cultural expectations.

This series, shaped by Mukazhanova’s reflections on the societal pressures faced by women in Central Asia, examine how gender expectations are perpetuated and internalized over generations. She describes her use of felt as an abstract, textured language for unpacking complex histories and norms that shape identity.

Nika Project Space Gallery Dedication to Central Asian Voices

Besides the main show and singular powerful pieces such as Mukazhanova’s, attention to Central Asian narratives was shared by a number of galleries in the stands. Among these, one of the most interesting was certainly the Dubai and Paris-based Nika Project Space.

While the Nika booth at Asia Now was entirely dedicated to Palestinian artist Mirna Bamieh, the gallerist Veronika Berezina has a deep commitment to showcasing the work of artists with roots in Central Asia.

Nika Project Space; image: TCA, Naima Morelli

“Many of the artists we work with have roots in Central Asia, whether they were born there or are part of the region’s vast diaspora,” says Berezina. One such artist is Alexander Ugay, a Kazakh-Korean photographer and videographer whose work explores the experiences of Central Asian immigrants.

Ugay is the creator of “cinema-objects” within the experimental collective Bronepoezd, which means “armed train” in Kazakh, of which he is one of the founders alongside Roman Maskalev. One of the most active figures in the Kazakh art scene, Ugay was educated at St. Petersburg University and Bishkek University in Kyrgyzstan.

Ugay’s video piece, “100,000 Times,” was featured in a group show at Nika Gallery last year. The work represents a group of Korean migrant workers from post-Soviet countries, with the single, displaced laborer, subject to the brutality of industry, seen as representing and reimagining the dissolution of an exploited community. In another piece, “Elsewhere in Unknown Return”, Ugay uses AI to re-visualize this community in archival form, centered around the 1937 Korean deportation, where multiple architectures of a mass exodus are created and algorithmic inputs adapted to produce accurate results.

As Berezina describes it, “Alexander’s work is deeply rooted in the lived experiences of Central Asians. He himself is part of the third generation of Koreans who were displaced to Kazakhstan during the Stalin era, and that sense of cultural dislocation and the search for identity is palpable in his art.”

Berezina’s own background as a Russian-born art patron has shaped Nika Gallery’s curatorial vision; “I was always drawn to art, even during my studies in international law,” she says. “When I decided to create my own gallery, it was important to me to focus on artists and practices that are often underrepresented on the global stage.”

By fostering these kinds of deep collaborative relationships with artists, Nika Gallery has established itself as a hub for cultural exchange and cross-pollination. Besides their presence at Asia Now, the gallery’s recent expansion to Paris further solidifies its role as a bridge between the art scenes of the Middle East, Central Asia, and Europe, offering audiences a chance to engage with Central Asian creativity.

As galleries, artists and curators continues to grow their practices and lines of research, it’s heartening to see an increasing number of new nuanced narratives from the Central Asian region coming to the forefront of the European art scene, and somehow becoming more and more relevant in times of “third cultures,” migrations, diasporas, and digital nomadism.

“Our goal is not just to showcase the work of these artists, but to create a space for dialogue and understanding,” Berezina says. “Central Asia is a region that is often misunderstood or overlooked, and we believe that art has the power to change that narrative, to bring people together, and to celebrate the diversity of human experience.”

This idea is also shared by Asia Now’s founder Alexandra Fain who, with this latest edition of the fair, proved that the Parisian event has remained steadfast in their commitment to amplifying Central Asian voices.