Credit: Pexels

Ratcheting up efforts in California to protect children from the negative effects of social media, Gov. Gavin Newsom has signed landmark legislation to combat the powerful “addictive” strategies tech companies use to keep children online, often for hours on end.

The legislation is the second of its kind in the nation, and is similar to a New York law signed by Gov. Kathy Hochul earlier this year.

The bill will prohibit online platforms, which are not named in the legislation, from knowingly providing minors with what are called in the industry “addictive feeds” without parental consent.

The bill also prohibits social media platforms from sending notifications to minors during school hours and late at night.

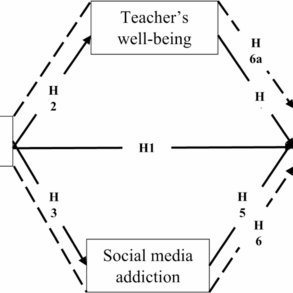

“Every parent knows the harm social media addiction can inflict on their children — isolation from human contact, stress and anxiety, and endless hours wasted late into the night,” Newsom said in a statement issued over the weekend. “With this bill, California is helping protect children and teenagers from purposely designed features that feed these destructive habits.”

Still on Newsom’s desk for his signature is a bill that would require school districts to limit student access to cellphones during school hours. Because Newsom called for school districts to do just that earlier this year, there is a strong possibility that he will sign that legislation as well.

Authored by Sen. Nancy Skinner, D-Berkeley, the legislation Newsom signed marks a growing effort to rein in the impact of all-encompassing technology that has revolutionized ways of communicating and brought significant benefits — but whose harmful effects on children are only now becoming clearer.

It is almost certainly the case that few parents, and even fewer children, are aware of the complex, and hugely effective, systems tech companies employ to keep users on their platforms, often for hours on end.

Addictive feeds are generated by automated systems known as algorithms and are intended to keep users engaged by suggesting content based on groups, friends, topics or headlines they may have clicked on in the past.

Instead, the law would make “chronological feeds” the default setting on social media platforms accessed by children. These feeds are generated only by posts from people they follow, in the order they were uploaded.

“Social media companies will no longer have the right to addict our kids to their platforms, sending them harmful and sensational content that our kids don’t want and haven’t searched for,” Skinner said.

The legislation follows Newsom’s signing of the California Age-Appropriate Design Code Act two years ago. Authored by Assemblymember Buffy Wicks, D-Oakland, it requires online platforms to consider the best interest of child users and to establish default privacy and safety settings in order to safeguard children’s mental and physical health and well-being.

The law expands on previous legislation approved by Congress in 1998, the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) and California’s Parent Accountability and Child Protection Act (AB 2511), approved by the Legislature in 2018.

The 2022 bill requires businesses with an online presence to complete a Data Protection Impact Assessment before offering new online services, products, or features likely to be accessed by children.

It also prohibits companies that provide online services from using a child’s personal information, collecting, selling or retaining a child’s physical location, profiling a child by default, and leading or encouraging children to provide personal information.

But its passage underscored the headwinds that efforts to regulate social media can run into. Immediately on passage of the 2022 law, NetChoice, a national trade association of online businesses, including giants like Amazon, Google, Meta and TikTok, filed a lawsuit to prevent its implementation. It argued that the law violated the First Amendment by restricting free speech and that companies would be limited in their editorial decisions over what content they could put out on their sites. A district court issued a preliminary injunction against the entire law. The state appealed its decision to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals which upheld parts of the lower court’s ruling, but allowed other parts of the law to go into effect.

It is not known whether tech companies will similarly challenge Skinner’s legislation.