- Forger tried to sell pieces in a gallery, but the gallery’s owner raised questions about the jewelry.

- Undercover agents purchased two pieces of jewelry from Charles Haack and began an investigation into what he said was authentic.

- Robert Haack initially pled guilty, then withdrew the plea. In the trial that followed, a jury convicted him.

A California man was found guilty of counterfeiting and selling jewelry by one of the 20th century’s best-known and beloved Native artists, a case that took 15 years to reach an outcome that is being applauded by other artists and collectors.

Robert Haack was found guilty of wire fraud, mail fraud and violating the Indian Arts and Crafts Act for selling faked jewelry on eBay by Hopi artist Charles Loloma in New Mexico. The verdict followed a four-day trial in late January.

Haack created and sold nearly $400,000 in fake Loloma jewelry before being charged, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of New Mexico, which outlined the case in a press release. Federal officials found raw jewelry materials, unfinished Loloma-style jewelry, engraving tools hidden in a boot, and metal shards where Haack practiced Loloma’s distinctive signature and design sketches in his home.

Liz Wallace, a Nisenan Maidu/Washoe/Diné artist whose own early work was influenced by Loloma, said the case is further evidence that people must shop very carefully for Native art. Even some “old hippies” make very good copies of Navajo jewelry, she said. All these counterfeiters cuts into Native artists’ livelihoods.

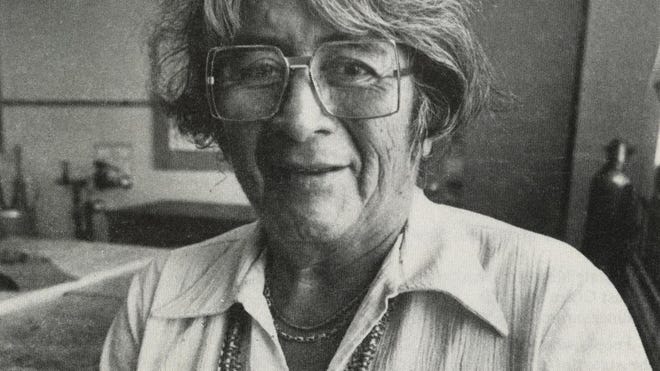

Charles Loloma — once rejected, now revered by collectors and crooks

Loloma is one of the most well-known Native jewelry artists of the 20th century. His work is distinguished by rich stones intricately cut, some inlaid in geometric or other patterns, some stacked on edge. Loloma used stones rarely seen in Indigenous jewelry like lapis, exotic woods or ivory.

Today, his work is featured in many galleries and museums across the Southwest. His authentic pieces can cost tens of thousands of dollars and are cherished by people who eagerly collect his necklaces, rings, belt buckles or earrings.

As The Arizona Republic reported in its 2024 series on Native art, Loloma’s work, although rooted in ancestral Hopi culture, was still cutting-edge in the mid-20th century and was initially rejected by Indian art markets as not being “Indian enough.”

Scottsdale Indian art dealer Bill Faust and his family have maintained a close relationship with the Loloma family, including Loloma’s niece and student, Hopi jeweler Verma Nequatewa “Sonwai.” Faust said he made the original complaint nearly 15 years ago after a man came to his gallery with what he claimed was genuine Loloma jewelry.

“It didn’t look right,” Faust said, “so I sent it to Verma, who also said it didn’t look right.”

Faust knew Loloma’s jewelry well, having watched Loloma making his art in metal and stone in his studio in Hotevilla as well as handling it in his gallery over the years.

When questioned, Faust said the man became testy and claimed it came from a disabled woman in Tucson who needed money.

“All these red flags popped out all over,” he said.

An investigation takes a winding road

The fakery fooled another dealer, who purchased the jewelry and resold it.

That’s when Faust went to the Indian Arts and Crafts Board, the federal agency that oversees the eponymous law that seeks to protect Native artists from being ripped off by counterfeiters.

In 2013 and 2014, undercover agents purchased two pieces of jewelry from Haack online. The pieces were confirmed to be fake.

A law enforcement officer from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the board’s law enforcement partner, led the formal investigation. Faust said that as part of the case, FWS officials followed Haack to the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show, where he bought materials to make jewelry using the same stones Loloma would have used: lapis lazuli, sugilite, pearls, diamonds and exotic woods.

People who had been taken in by Haack started stepping forward to help. Faust said one woman who had bought some counterfeit pieces from Haack allowed the jewelry to be taken apart so the stampings could be verified as fake. Another one loaned her pieces for examination, he said. But one woman who purchased items that proved to be worth only 10% of what she paid declined to be identified, Faust said.

In the middle of making the government’s case, the investigator unexpectedly died, which Faust said delayed the case by at least three years.

It wasn’t until 2021 that Haack finally agreed to plead guilty to wire fraud and violating the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, which states that only Native Americans can market art as being Indian-made. And another two years would pass before U.S. District Court Judge Martha Vázquez rejected the plea agreement. Haack decided to try his luck in court and pled not guilty.

Faust himself was brought in to appraise the pieces and Nequatewa testified in court.

It took jurors just four hours to determine Haack’s guilt.

Faust said Haack’s actions were like cheating his own family.

“There are enough of us dealers who care enough about this industry that we will come after you,” he said.

Art world:What’s real and what’s fake? In the Native art world, the question is hard to answer

Fake Native art is a ‘slap in the face’

Wallace, who’s also an advocate in the fight against counterfeit Native art and a jeweler, lauded the hard work of the prosecutors and agents who continue to pursue the tough work of investigating and prosecuting counterfeiters.

“They really do care about protecting Native American artists,” said Wallace. “They want to do something good for Native people.” She has worked with prosecutors to help get these cultural and financial thieves off the street and fake Native art off store shelves.

Despite just a day’s notice, Wallace made it to the trial. She said Loloma’s niece Nequatewa spoke eloquently about her uncle’s legacy, including his spirituality and artistry.

“I hope there’s jail time for him,” Wallace said.

“It’s really a slap in the face that someone so iconic who took Native art in a new direction gets counterfeited,” she said.

In addition to the cultural and artistic theft, fake art and the criminals who make it are consuming authentic materials like turquoise, red abalone, jet, spiny oyster and other such materials, which creates shortages for the Indigenous artists who depend on it.

And unlike counterfeited brands like Louis Vuitton, which seem to gain publicity and more business when they’re copied, fake pieces hurt Native artists who depend on the income from their creations to feed their families and pay their bills, she said.

But, Wallace said, she sees progress being made. “Previously, offenders got away with just a fine,” she said. Recently at least two other major forgery cases resulted in convictions. A group selling products made in the Philippines as Alaska Native art was sentenced to jail time and home confinement. Two men in Gallup, New Mexico, pled guilty to selling imported pieces as genuine Native art.

Even more importantly, though, Wallace said reproducing Indigenous art removes it from its cultural context.

Ironically, Faust said, Haack’s work was well made.

“He could have sold that stuff all on his own and done well,” he said. “He didn’t have to imitate Loloma.”

Debra Krol reports on Indigenous communities at the confluence of climate, culture and commerce in Arizona and the Intermountain West. Reach Krol at debra.krol@azcentral.com. Follow her on X @debkrol.

Coverage of Indigenous issues at the intersection of climate, culture and commerce is supported by the Catena Foundation.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content