Nothing grows in the shadow of a tall tree.

(Constantin Brancusi)

Looking forlorn and somewhat cross from an early photograph, Camille Claudel makes me feel as if I’ve done something to displease her; or else she is just very young. I explain the pout as a sign of the latter. It is a year of anniversaries, and the Rodin Museum in Paris, which I enjoy revisiting, celebrates the 160th birthday of one of the few women sculptors.

Known widely as Rodin’s muse and mistress, also as Paul Claudel’s sister, Camille Claudel is a major figure in the competitive world of 19th-century European sculpture. A young woman from a nice bourgeois family was not expected to practice art beyond the level of a hobby, even less to choose sculpture, which was viewed as a masculine pursuit. But the artist held her own, working with difficult materials, choosing challenging subjects, creating bold compositions.

On her journey from pupil of Alfred Boucher then of Rodin, from Rodin’s model to his lover and emulator, to an independent female artist, Claudel had to struggle with the prejudices of a patriarchal society as well as her own emotions: Rodin, her master and idol, was 24 years her senior and in a long-term relationship.

The dance and the allegory

Claudel’s sculptures are realised from the inside out: the heart of the work existed before it took its form: a crouching woman, a group of chatting girls, a couple of dancers. In her work, volumes are more important than features, emotion scores higher than mimesis.

The first version of what was to become her most famous sculpture, La Valse, created during a happy period of her life with Rodin, was also the most erotic. Man and woman are held in a moving embrace; they appear to rise from the vegetation at the base of the sculpture, which climbs up and covers the woman’s leg in a languorous, sensual ascent. The sculpture leans at a precarious angle, the couple suspended in the moment before falling or flying. But the man’s strong, elongated arm and large hand is holding the woman’s waist firmly; they continue to float elegantly in a ludic, undulating rhythm.

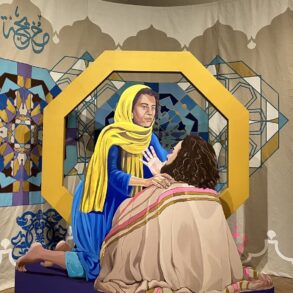

The ascendant diagonal composition is also present in the 1888 L’age mur (The Age of Maturity). Propelled by the invisible force of time, three figures are advancing towards the inevitable destination. The man at the centre is held by an older woman who is pulling him forward, while a kneeling young woman appears to have just released his hand, reluctantly abandoning her efforts to retain him. The passion, the abandonment, the agony are palpable. According to the title, it is an allegory of life: man has to leave youth behind, and eventually, inevitably, old age wins the contest.

The work has also been interpreted as representing the love triangle that marked that period in the life of Claudel. Her brother believed the young woman in the sculpture is “my sister Camille, imploring, humiliated on her knees.” If this is not a valid interpretation, and the work is not autobiographical (Rodin staying with his older mistress Rose Beuret and abandoning Claudel), some have wondered why Rodin was so infuriated by this sculpture as to withdraw his support for his former pupil.

The sisterhood

The naked young woman, carrying a sheaf of wheat on her back shows the influence of Rodin in Claudel’s work. The dramatic posture, the solid legs, the interlocking knees, are reminiscent of her master and colleague (at the time they were working together on the Gate of Hell). But the gentle and alert profile, the arm folded over one breast, a gesture used also in The Abandon, The Injured Niobide and The Waltzer, are as much Claudel’s signature as her name engraved in the 1886 terracotta. August Rodin’s Galatea, a sculpture dated three years later, is uncannily similar.

As in many of her works, the Flute Player’s body is dedicated to its action: knees together, feet clasping the rock on which she sits, the gentle curves emphasise the tension of the legs and the arching of the back. The head turns gently towards her shoulder, the arms form a loving circle around the instrument, the player’s mouth nearly, but not quite, touching the flute, as if ready to give it a kiss, or a breath. Light fabric, in the style of Art Nouveau, and the music give the siren wings.

With Les causeuses (The Chatterers) Claudel ventures into more complex compositions, at a time when she was also experimenting with different materials. Inspired by a group of women chatting on a train, the small sculpture features four women in a circle, sharing a secret. We see the curved backs of three women, their heads tilted together, leaning forward towards the speaker, better to hear her. Facing us, she must be whispering, a hand reaching to her lips emphasising the secret nature of her words. The group are huddled in a corner, formed by right angled walls, or a niche like a grotto on a stage. The women are naked, the artist highlighting the roundness of their bodies, indicating the idea of ‘everywoman’.

The theme of women’s camaraderie, the platonic intimacy of female friends is reprised in The Wave, a small onyx marble and bronze sculpture. The three women hold hands and bend their knees playfully in anticipation of the big wave (possibly inspired by Hokusai). Claudel’s choice of material for this work was seen by some as her decision to produce decorative pieces, as befitted a young bourgeois lady. It is doubtful that it was the artist’s intention. As in The Age of Maturity, Claudel reflects on the human condition, on mortality, on destiny. Fortunately, but mysteriously, The Wave is one of the few pieces Camille Claudel did not destroy when she left her studio for ever.

Of art and passion

Claudel’s love story, of two artists working together and inspiring each other, in which the man dominates, is not unique, but it is uniquely tragic. By all accounts, her talent was exploited in Rodin’s studio, while she worked for his large commissions on which only his signature appears. They made portraits of each other: Rodin sculpted about 12 portraits of Claudel. There is only one bust of Rodin by Claudel: it shows a ‘man of the people’, with a prominent nose, a rich moustache, solid facial architecture. His beard runs as a river, covering the lower part of his face, an expression of masculinity. Claudel may have been a more subtle, a more perceptive reader of the character behind the physical features. Of the two, Claudel may have been the greater sculptor.

Constantin Brancusi ran away from Rodin’s studio after just one month. Claudel, still a teenager, fell in love with Rodin—the artist, the teacher—and stayed. And Rodin always supported her, until The Age of Maturity. Was this, as some believe, because he regarded the work as an indiscretion, a representation of the love triangle that tormented her? Or was he infuriated by that proof that his talented student could surpass the master?