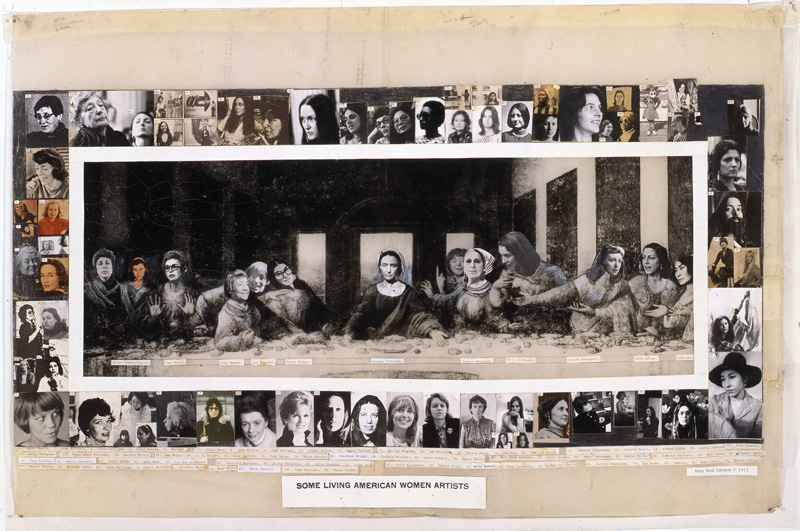

Mary Beth Edelson’s best known and most widely distributed work may be Some Living American Women Artists/Last Supper (1972) in which she replaced and framed Christ and his disciples in Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper with photographs of more than 80 women artists. Edelson meant for her “Dada gesture” to operate on a number of levels, making room for women in a male dominated art world while also taking on a male dominated religion.1SLAWA, as Edelson refers to this work, can also be interpreted as a symbolic performance by an imagined community of living women artists, many who did not (yet) know each other personally. Linda Aleci writes that Edelson “honors the ecumenical ideals of communion and community.”2 To these two ideals I would add connectivity or in more contemporary terms, an attempt at equal access. In this way, SLAWA can be read as a kind of analog or proto-social media network that involved envisioning a more feminist future.3

Today the original SLAWA collage resides in the permeant collection of the Museum of Modern Art alongside Edelson’s, Death of the Patriarchy/A.I.R. Anatomy Lesson in which she recasts Rembrandt’s group portrait with 26 of the earliest members of A.I.R. Gallery. Edelson serves as chief doctor with the privilege of taking the first stab. Although MoMA first exhibited SLAWA in 1988 in Committed to Print, the story of the dissemination of print editions of the work speaks more to Edelson’s involvement in building feminist community and social connectivity. As early as 1972, Edelson printed SLAWA in an edition, making it readily available for wide distribution as she understood the work’s great potential for instigating future connections and opportunities. In the pre-internet world SLAWA served as a map or archive for women artists looking for each other. Curators also came to know the names and faces in the print as it hung in homes, studios, and offices across the United States and abroad. In the 1970s SLAWA, in combination with Lucy Lippard’s Women Artist Slide Registry of more than 600 images, was evidence of women artists’ greatness, or at least their existence. These two “archives,” considered together, made it possible not only to discover the work of women artists but also to offer a manner by which to locate them. Many of the women who founded A.I.R.— the first all-women’s gallery in the United States, which opened the same year SLAWA was created—found each other’s work through the Women Artist’s Registry and most are also pictured in the print.4

Mary Beth Edelson went on to repurpose images from SLAWA as the raw material for a series of wall installations that are discussed in depth by art historian Kathleen Wentrack in multiple essays, including Mary Beth Edelson: Humor is the Best Game in Town:

Many of the wall collages record women active in feminist art groups, but they also function as historical documents that describe the organizational and the working processes of a community in the process of implementing a revolution. The web-like shapes in the wall collages break from the confines of framing to visualize the collective and collaborative structures of these groups who are not represented in rows but are connected to each woman through the next.5

These “living documents,” or archives-as-art involve connections, both real and imagined, layered with winding snakes, birds (and women) in flight, Medieval Sheela-na-gigs, and other iconography Edelson associated with weaving a new feminist canon of (art) history.6

Not surprisingly, Mary Beth Edelson’s life has involved organizing and connecting communities from early on.She was born in 1933 in East Chicago Indiana. From age 13, Edelson participated in the Civil Rights Movement, working to integrate the local Methodist youth group. After graduating from DePauw University in 1955 with a degree in Fine Art, Edelson briefly performed with a traveling modern dance troupe. Between 1958 and 1959 Edelson resided in New York City and completed a MA at New York University. After a brief period teaching at Montclair State College that ended due to the lack of further opportunities for female professors, Edelson relocated to Indianapolis where she continued to be active in meetings, demonstrations, and other civil rights initiatives, learning strategies for group process she would later utilize in collaborative feminist workshop-based performances. Edelson’s experience as the co-founder of the Talbot Gallery in Indianapolis would also inform her later work as a member of the Heresies Collective and of A.I.R. Gallery. Edelson’s early experiences with an art world in which almost 98% of all galleries nation-wide did not exhibit any women artists also fueled her interest in addressing the status of women and connecting women artists to each other and to the broader art world.

Between 1968 and 1973, Edelson lived in Washington D.C., where she co-organized the first National Conference for Women in the Visual Arts at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, bringing together women artists from across the country, many who had never met previously.7 In 1972 Edelson embarked on her first major collaborative works. For 22 Others Edelson invited 22 friends and colleagues to suggest a theme for a new piece. A prompt from fellow artist, Ed McGowin resulted in Some Living American Women Artists: “organized religion as a point of departure, [and] expose whatever negative aspects of organized religion might occur to you-making the political, social and philosophic implications clear.”8

According to her own account, Edelson didn’t know the majority of the women she included in SLAWA in 1972:

My selection for the central panel was fairly arbitrary. That is, they were not political choices based on personal associations, but were instead focused on diversity of race and artistic mediums. The border included every photograph of a woman artist that I could find, with most of the 82 photographs coming directly from the artists themselves.9

Edelson’s own writing about SLAWA, as well as that of other contributors to the collage are included in her 2002, self-published book, The Art of Mary Beth Edelson. The book also “reads” like a network of connections or an edited archive of Edelson’s career interwoven with those of many other women artists. Like connections one follows through Instagram today, Ana Mendieta, Carolee Schneemann, and Nancy Spero feature especially prominently in Edelson’s book due to their personal relationships, collaborations, and mutual interests. In one section, Edelson shares images of letters from women she wrote to requesting portraits for SLAWA. Edelson recounts mailing complimentary copies of the print to each artist in return.10 Still, one wonders how Edelson decided who to contact exactly. There must have been some “who knows who” involved in creating a list of names and naturally, if unintentionally, leaving out others. Although it is a work of a different physical scale, the research that went into uncovering the names of the 1,038 women throughout history who are represented or named in Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party took numerous researchers and collaborators a number of years to compile. But unlike Chicago’s largely historical project, the living women in SLAWA were able to appreciate their inclusion, which we know many did from the letters Edelson received. June Wayne, artist and founder of the Tamarind Lithography Workshop hung the print in her Los Angeles studio and sent Edelson Georgia O’Keeffe’s address in New Mexico so that O’Keeffe might also obtain a copy.11 One can only imagine how many individuals viewed SLAWA in these and other locations, as well as in the numerous publications that Edelson allowed to reproduce the image over the years.

Today some argue that the Internet and social media have a leveling effect, at least for those who can afford easy and consistent access. Yet there is still knowledge that feels out of reach, saved only for some, and there are those who feel that no one is looking for their faces or their stories. 90% of project contributors on Wikepedia in 2018 were men, for example, thus the recent push for equalization through events such as Art + Feminism Wikepedia edit-a-thons.12 To dig deeper into the women pictured in SLAWA or discover others who are unnamed is a challenge even for someone like myself with an academic association and with the privilege of working with some of these women, or at the least with their work. The algorithms for social media platforms skew what we see while at the same time to view materials housed in most academic archives involves time, cost, or even credentials that are often prohibitive. The younger version of myself who waited for a zine to arrive via snail mail in the hopes that it would contain the names and faces of women musicians and makers I didn’t know of yet, now wants every person who can search the word “zine” to be able to access materials like the Riot Grrrl Archive at Fales Library and Special Collection at New York University. I want them to be able to look up not only the finding aid with a list of names (thank you to our librarians for this!) but also the rich, visual materials. Unfortunately, a small portion of archives of this kind are digitized for reasons including the immense cost and labor involved in such a project. And then where do we store everything?

In 1972 Edelson gave us some names and faces to start with, making a visual archive that pointed us in the direction of more than eighty women she thought we should know. Certainly, there are other women artists, especially additional women of color that could and should have been added. Today what we choose to make and share in digital format may define who we are and how inclusive the web (real, imagined, or digital) that makes up our feminisms will be in the future. Surely Edelson understood the power of making visible that which had previously been unvisualized and unnamed in the mainstream as far back as her involvement with the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. In 2016 what America really stands for, and stands upon, has been and should be questioned again. Maybe more specifically for this column and this paper it still seems worth asking some questions about who gets to keep LIVING (here?), who gets to be AMERICAN, who gets to be considered WOMEN and which people are supported and recognized as ARTISTS? Certainly, images coming out of Standing Rock that were watched or broadcast via social media as well as those images at airports and borders also speak to some of these questions.

In 2020, a SLAWA print will be exhibited at the Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton college in an exhibit that examines the ways artists map and diagram themselves and their communities. In part an homage to Edelson’s contribution, the exhibit—organized by Matthew Deleget and Rossana Martinez of Minus Space—is succinctly titled, Sum Artists. Among the artists are Ryan Elizabeth Feddersen whose “Indian Boarding Schools” series map the results of government policy under which “native children were rounded up and forcibly held by religious, military, and industrial organizations in boarding schools that systematically eradicated native culture, language, and religion.”13 Among other things, Feddersen’s work questions, as we must today, what is, was and shall be America? The Guerrilla Girls, our perennial conscious and the avid counters of the art world, will also be part of SumArtists (“How many women artists and artists of color are included in the pages of each issue of this and other art publications,” they might ask?) This essay is part of the section of this publication that is a special project of the Feminist Institute, an organization whose moniker reads: “equalization through digitization.” The Feminist Institute follows in Edelson’s future minded footsteps, with their interest in equity and access. I am hopeful that this organization can offer something that adds to and builds on Edelson’s capitalized call to make visible Some Living American Women Artists, while at the same time considering how that project should also look different today than it did in 1972.

Mary Beth Edelson’s personal archive is owned by the Fales Library and Special Collections at New York University. Through a partnership between Fales, Google Arts and Culture and the Feminist Institute much, if not all of Edelson’s archive will be available online to the public in the near future.

- Linda S. Alci, “In a Pig’s Eye: The Offence of Some Living American Women Artists,” in The Art of Mary Beth Edelson, 2002, New York,p. 32.

- Ibid.

- Dena Muller and I are both former directors of A.I.R. Gallery where Edelson exhibited in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Some of the interpreting of SLAWA comes out of our ongoing conversations.

- These networks of connections are traced most thoroughly by Meredith Brown in her essay, “The Enemies of Women’s Liberation in the Arts Will be Crushed”: A.I.R. Gallery’s Role in the American Feminist Art Movement,” https://www.aaa.si.edu/publications/essay-prize/2012-essay-prize-meredith-brown

- Kathleen Wentrack, “Mary Beth Edelson: Humor is the Best Game in Town,”http://outpostnycdcg.com/projects/mary-beth-edelson-essay/ Accessed 19 January 2019.

- Wentrack.

- Edelson, “The Art of Mary Beth Edelson,” 12.

- Ibid, 32.

- Ibid, 32e.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 33.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender_bias_on_Wikipedia Accessed 28 January 2019.

- Ryan Elizabeth Feddersen, “Kill the Indian Save the Man – Borderlands,” http://ryanfeddersen.com/kill-indian-save-man-borderlands/#more-1170 Accessed 28 January 2019.