When it comes to Old Master works, many of us think immediately of art made by men—most often Caravaggio, Rembrandt or Vermeer. But there were women artists working in the Early Renaissance all the way through to the Romantic era. It’s just that their work was often overlooked or outright ignored.

That’s changing, thanks in part to the New York-based curator Dr. Virginia Brilliant—who, it must be said, has the best name ever. “Whenever someone calls me ‘Dr. Brilliant,’ I feel like a Bond villain who should be stroking a bald cat on a desert island,” she is known to quip.

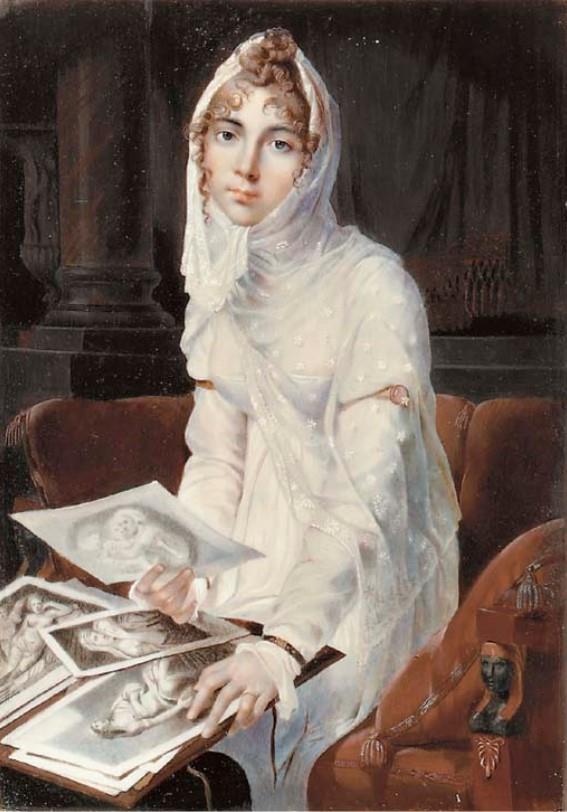

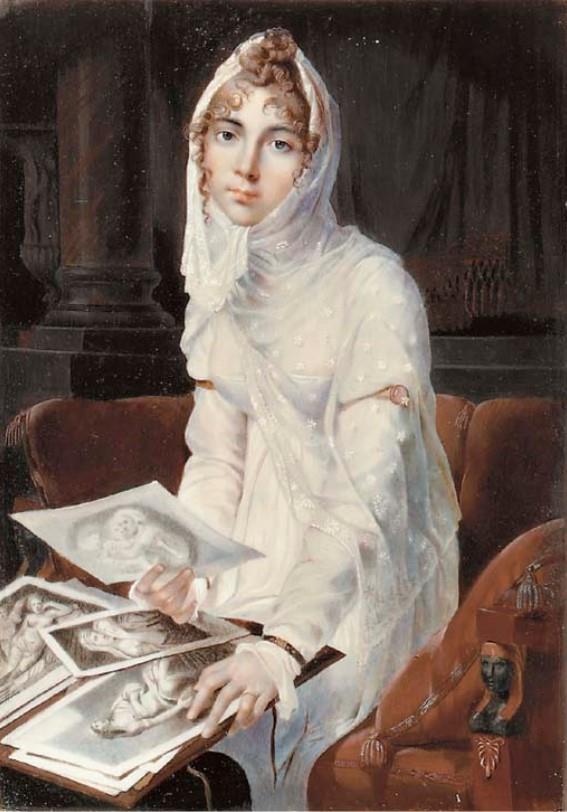

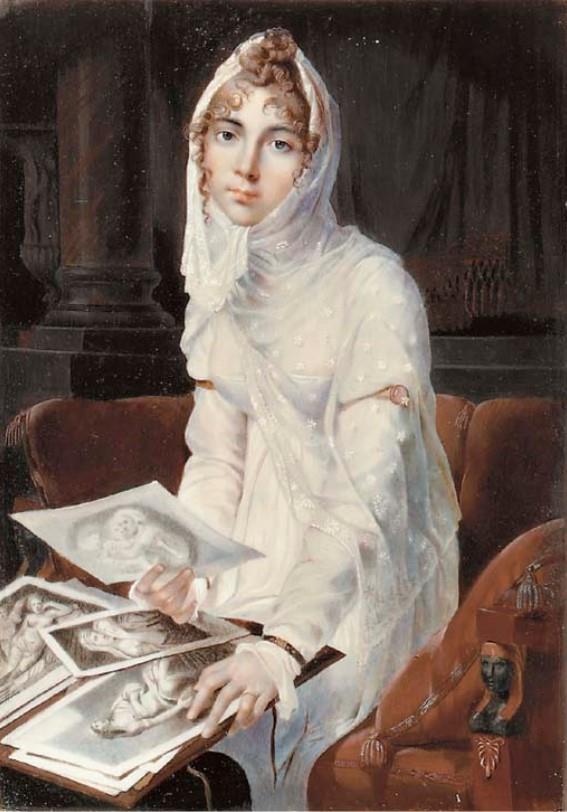

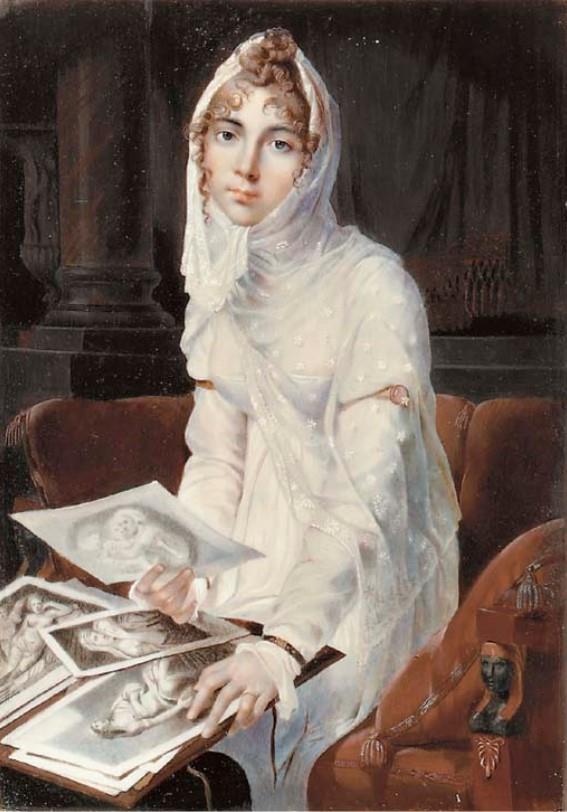

Most recently, she has put together an exhibition featuring artworks by a group of women who might reasonably be called the Old Master Women. “Ahead of Her Time: Pioneering Women from the Renaissance to the Twentieth Century” is on view at Robilant + Voena in New York City through February 10.

The exhibition features thirty stunning artworks by women artists from across Europe, the U.K., and the U.S., bringing to light a number of treasures usually hidden away in private collections. “This isn’t art you’ve typically seen in an art museum,” said Dr. Brilliant.

Expect to see artwork from the Renaissance and Baroque periods, especially from 18th- and 19th-century France. There are also artworks from Italy, including 16th-century paintings by Lavinia Fontana (trained by her father, Fede Galizia, who famously painted still life fruit bowls) and Orsola Maddalena Caccia, who was a nun. One rarely seen artist on view is Artemisia Gentileschi, whose paintings are a recent discovery.

Brilliant spoke to Observer about the challenges these women were up against, the long history of sexism in art and why Robilant + Voena painted the gallery walls pink for this show.

How do you define an “Old Master” artist and how many women artists would be on that list?

I was a museum curator for fifteen years, and the Old Master women artists were never a focus of attention. But I heard the same thing from several museum curators—that they want to add women artists to their collections. We need to address this balance. There’s an essay written by Linda Nochlin called “Why were there no great women artists?” from 1971. That started it.

What did it say that resonated with you the most?

Nochlin said that with the 1960s came feminism and more women academics, who were interested in these questions. They realized there were great women artists, but they weren’t properly studied because there weren’t women academics who wanted to take these topics on. There’s been a boom in sorting out these women, their careers and their lives, and we’re still learning more about them. Museums are learning this has to be a priority.

What is the earliest piece in the show?

Our earliest piece is a 1598 painting by Italian artist Lavinia Fontana, who is recognized as the first woman to achieve professional success as an artist. She had a husband and twelve children, on top of her career. Robilant + Voena specializes in Italian Renaissance and baroque artworks. Since the exhibition is in New York, I wanted to include some American artists, too, and since we’re a British company—though my bosses are Italian—I couldn’t resist including some British women artists in the show.

Let’s talk about these women. What did they have to overcome in their lives?

Let’s look at women writers. What did they need? A room of one’s own, so to speak, and paper and a pen. But in the visual arts, you needed professional training. These women were mentored by their fathers, who luckily trained them and helped them travel. Women were expected to marry early on. Work-life balance wasn’t easy for women, just like it isn’t easy now. Many women artists who stayed unmarried until later (or not at all) were more prolific.

How were women discriminated against in the art world back then?

Even in the late 18th Century, women weren’t allowed to train at the same art academies as men. Women weren’t allowed to draw nude figures. Biblical art was considered the most important of all the genres. Women were limited to painting portraits and still life artworks, like fruit bowls. Some women artists were clever, teaching themselves how to draw the human form by studying sculpture. They found their own ways around the restrictions. In France after the French Revolution, some women artists even trained young women artists to show that women support women.

Let’s talk about Rosalba Carriera—what made her story so remarkable?

She was a super interesting case, revolutionizing painting. She was collected by major courts throughout Europe, and she trained and worked in Venice. She hit the right thing at the right moment. Men traveling through Venice wanted their portraits painted, but they couldn’t necessarily afford the time or the funds to sit for a big portrait in Rome. So, she was hired to paint them for a smaller fee.

What about British artist Mary Beale?

She started as an amateur painter; she was encouraged to pursue painting. Her business supported her entire family, and her husband became her studio assistant. He kept detailed records of all of her work, which was hugely helpful.

What do you think about the female gaze in painting from this time?

Women had to use themselves as subjects for their work. When women painted women, they painted them with a strength and an honesty we didn’t see in paintings by men. A man might have painted a woman with an idealized eye, if that makes sense. Fede Galizia did this well, and she has one of the most stunning pictures in the exhibition—it’s a real new discovery. This is a subject she painted several times over twenty-five years. Since her father was a miniaturist, there’s an acute attention to detail. She traveled to Turin with him, and her art style evolved through the influence of the changing world around her. It’s stunning to see her growth as an artist. It revolutionized her style.

Why did you paint the walls of this exhibition pink?

I was worried it would look like my bedroom walls looked when I was six years old. My bosses were in town from London, and they have an Italian decorator friend who suggested we choose this particular hue of pink called Cinder Rose. Frankly, I was worried it would be too girly, but it’s perfect.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content