Abstract

This study aims to analyze the fake posts circulated on Turkish social media during the Russia–Ukraine war. With advancing technology, social media platforms have a profound impact on the way we perceive and interpret events and make us question the accuracy of information generated about international events such as wars. While the Russia–Ukraine war constitutes an important turning point in international relations, the reflection of these events on social media is also seen in fake posts. In this context, the main purpose of this study is to identify the common themes of fake social media posts and to reveal the general context of these posts on social media. In addition, the study aims to analyze the fake content circulating on Turkish social media and to reveal the emerging polarized discourses through the identified themes. The research revolves around five main themes that feed polarization: war reporting, ideological misrepresentation, humor, hate speech, and conspiracy theories. The findings show that fake content is particularly concentrated around ideological polarization and antagonisms. It was also found that misinformation and decontextualized humor blurred the true context of the war and that fake content combined with hate speech and conspiracy theories distorted the context of the war.

Introduction

In recent years, the prominence of fake news and contents has grown significantly, capturing widespread attention in the global information landscape. Despite its long-standing presence in the public sphere, the dissemination of misinformation and propaganda has only recently garnered significant recognition. This heightened attention towards fake news and contents has been driven by major events such as the 2016 United States Presidential Election, the global Coronavirus pandemic, the development of COVID vaccines, and Russia’s military actions in Ukraine. Consequently, fake news has become a highly visible phenomenon in both traditional and social media, profoundly impacting society and the consumption of news (Farkas and Schou, 2018).

As the global recognition of the problem of fake news continues to grow, an increasing number of studies have been conducted to examine various aspects of the issue. These studies encompass the extent of fake news consumption, the reasons behind online dissemination of fake news and the potential use of social media curation to counter its spread (Marwick, 2018). Since 2016, major world events and the easy access to diverse forms of media, coupled with the boundless possibilities for creating and sharing news and posts on social platforms, have provided an ideal environment for the proliferation and distribution of fake social media posts.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has not only caused the spread of negative effects such as panic, fear and violence, but also triggered broader social problems such as polarization and ideological divergence. Especially on social media platforms, there has been a significant increase in polarization and ideologically polarized representations of the Russia–Ukraine war. This contributes to the dissemination of fake news and posts, as well as distorted or manipulated information in support of a particular political view or ideology. Therefore, addressing and examining fake posts on social media in the context of war can provide insights into polarization and ideological divergence on social media. This study uses multimodal discourse analysis to examine fake posts spread on Turkish social media in the context of the Russia–Ukraine war. 204 samples were obtained from four fact-checking platforms, Teyit.Org, Doğruluk Payı, Doğrula, and Malumatfuruş based in Turkey. The selection criteria for these sites were their active analysis of the war in Turkish, continuous interest, and timeliness. The aim of this study is to uncover the themes of fake posts circulating on Turkish social media regarding the Russia–Ukraine war.

In this context, this study is addressing the following question:

In the context of the Russia and Ukraine war, which discursive themes are shaped around the fake social media posts circulated on Turkish social media?

Fake social media posts and fake news

In today’s digital age, the unregulated nature of social media platforms has facilitated the widespread dissemination of false information, commonly known as fake news. The rise of fake news has been particularly evident following the 2016 US Presidential election, where the lack of verification systems and editorial filters on social media platforms allowed misinformation to flourish (Allcott et al., 2019).

The definition of “fake news” has been a subject of intense debate and evolution over time. Some scholars, exemplified by Walters (2018) focus their attention on the content of communication, assessing its veracity. Conversely, other researchers, such as Badawy et al. (2018), direct their focus towards the sender’s intent to sow discord and distrust in the political system. However, an increasing number of academics have moved away from offering normative definitions of fake news, preferring to conceptualize it as a “floating signifier.” This characterization portrays it as a term caught amidst different prevailing narratives, each seeking to shape perceptions of societal norms and structures (Farkas and Schou, 2018, p. 298). Despite the fluidity in its meaning, the use of “fake news” as a rhetorical tool, particularly in the context of power struggles involving elites, remains a consistent theme in scholarly discourse (Brummette et al., 2018; Farhall et al., 2019; Van Duyn and Collier, 2019).

Fake news refers to intentionally deceptive or completely fabricated information that is designed to mislead its audience (Tandoc et al., 2018). It can be created with malicious intent to cause harm and disruption, or for personal gain and political motives (Khaldarova, Pantti (2020); Gallagher and Magid, 2017). Crises, such as pandemics, wars, and revolutions, often become breeding grounds for fake news, as it capitalizes on people’s fear and anxiety, often exaggerating events beyond reality. The COVID-19 pandemic, for example, has seen the rapid spread of conspiracy theories and fake news, leading to widespread fear and suspicion among the public (Brown, 2021).

The ease of access to a vast array of information through social media platforms has made it possible for individuals to encounter contradictory and misleading information that contradicts official statements (Newman et al., 2020). This exposure to misinformation has been likened to a virus, as users unknowingly spread false information to others. Efforts to combat fake news are often compared to antivirus software, aiming to identify and quarantine harmful false information before it can harm its intended targets (Chen, 2017; Derman, 2021).

The issue of the impact of social media platforms on the prevalence of fake news during conflicts like the Russia–Ukraine war has raised concerns. The role of social media in shaping dominant and popular opinions has been a heavily debated topic in Turkey, particularly since February 2022 when the invasion in Ukraine escalated.

The internet and social media platforms have become primary channels for the dissemination of information, allowing for the manipulation and spread of disinformation by both state and non-state actors. This blurs the line between truth and falsehood, challenging the role of traditional media as the sole source of information. In environments where disinformation thrives on social media platforms, perceptions of reality become fragile, and artificial agenda-driven narratives become prominent. Social media constructs a public space that manifests as the mass consumption of simulated realities, highlighting social, cultural, and ideological illusions. Social media platforms have a dual nature when it comes to news consumption. On one hand, they offer low-cost, accessible, and rapid information dissemination, leading to increased news search and consumption. On the other hand, they facilitate the spread of fake news, referring to intentionally false or low-quality information (Shu et al., 2017; Waisbord, 2018; Wardle, Derakshan, 2018).

Due to the dynamic nature of social media, compared to news in traditional media, issues such as fake contents and posts, baseless rumors, misinformation, and disinformation spread much more rapidly on these platforms (Chaudhari and Pawar, 2021: p. 59). During peak periods of international crises, people tend to share more content related to the subject through their social media accounts (Haq et al., 2020: p. 216). Conversations taking place on social media often escalate into a duel among citizens of crisis-affected countries. The prevalence of disinformation is frequently encountered in such networks, given the broad societal participation (Sacco and Bossio, 2015: p. 68). Social media platforms serve as crucial intermediaries in delivering information to the general public regarding specific matters.

The term “fake” inherently implies an intent to deceive and mislead. It is closely linked to the concept of counterfeiting and mimicking something real (Fallis and Mathiesen, 2019). This is done with the purpose of manipulating and duping readers into believing that the fake news is real (Lazer et al., 2018). In this context, the term “fake posts” has been used as an umbrella term based on the idea that, after circulating, the effects of fake contents on social media can resemble a news article or a misinformation/disinformation-driven news post. It is worth emphasizing that our focus is on contemporary contents, specifically in the online realm, where false information is widely disseminated throughout the digital landscape, particularly on social media platforms. In this study, the term “fake post” is used to cover profiles that are news pages that publish fake news, as well as examples of users who share fake posts, shape them with their own personal views and opinions, and re-circulate them. The most important reason for this is that fake social media posts can circulate on social media platforms like “news”, drawing from individual opinions and perspectives. Fake news can manifest as a post (on X platform, for instance), mirroring the presentation style of real news on these social media platforms, including headlines, images, and source attributions.

Fake social media posts and polarization

The emergence of internet broadcasting as a competitor to traditional media and the broad acceptance of social media have significantly influenced the trend of polarization (Lelkes et al., 2017). Conversely, divisive content, including fake news, spreads rapidly across social media platforms (Yu et al., 2021). Controversial posts are often sensationalized, attracting significant interaction and spreading quickly. This dynamic also reflects the social and political polarization seen on social networks (Gürocak, 2023).

Polarization emerges in a society when the multitude of ways people understand and interpret life, along with their interests and identities, begin to coalesce into opposing dimensions, dividing into two contrasting camps. This signifies a sociopolitical situation where individuals’ group identities become decisive and guiding in any political debate, aligning multiple identities and interests not around specific points of intersection, but rather around a particular division (García-Guadilla, Mallen (2019), p. 63–64; McCoy and Rahman, 2016, p.13). Therefore, one of the most distinct characteristics of polarization is the concentration and reinforcement of societal and intra-country differences into two primary groups. It is precisely at this juncture that a sharp distinction between “us” and “them-the other” emerges within/among these groups. As pointed out by Al-Rawi and Prithipaul (2023), the connection between misinformation and polarization can be approached from these two perspectives. First, Yang et al. (2016) elucidate how exposure to social media content can heighten individuals’ perception of polarization, especially when confronted with “an extreme exemplar from the other side of the political spectrum” (p. 36). Also, Au et al. (2021) propose a three-stage model explaining how misinformation leads to polarization. The model suggests three stages through which misinformation drives polarization. Initially, misinformation is produced for political or financial motives. Subsequently, it spreads quickly on social media, fueled by a collective urgency and cognitive biases that promote rapid sharing. Ultimately, this leads to polarization, caused by either the overgeneralization of abundant information or personal attacks from political leaders or internet users.

In Turkey, social media, Twitter, has emerged as a battleground for managing polarization. Given the hybrid media landscape, social media platforms offer opportunities for small independent media outlets to amplify their voices, especially when mainstream media faces political pressures. However, this potential for amplification also opens avenues for incumbents to exert pressure on alternative media platforms. To sway online public discourse, for instance, employees of the ruling party have been reported to create fake accounts and orchestrate cyber-attacks against the opposition on Twitter (Bulut and Yörük, 2017; Kocak, Kıbrıs, 2023).

Turkey is now widely acknowledged as one of the most polarized nations globally, as evidenced by various polarization metrics (Aydın Düzgit, 2023). Therefore, in order to understand the social media context in Turkey and to reveal the impact of fake social media posts, it is imperative to underline the extent of polarization in the country. Studies have demonstrated that fake content can readily circulate within these polarized structures and communities on social media platforms. In line with this, Erdoğan and Semerci (2022) suggest that Turkey has long grappled with various forms of polarization, which persist to this day, significantly shaping contemporary politics and social dynamics. Also they argue that polarization along axes such as right–left, center–periphery, secular–religious, and Turkish–Kurdish has deeply influenced Turkey’s sociopolitical landscape across different historical epochs.

The Turkish media landscape is characterized by a strong alignment between media outlets and political parties, leading to significant polarization (Çarkoğlu et al., 2014). News organizations in Turkey often adopt framing strategies that mirror the agendas of their associated political entities (Panayırcı et al., 2016). Individuals frequently gravitate toward media sources that echo their own political leanings. Moreover, polarization heavily influences the nature of public discourse on social media platforms. For instance, only a quarter of users express willingness to engage in discussions about contentious topics on social media (Erdoğan and Uyan‐Semerci, 2018).

According to a report published by the Social Democracy Foundation (SODEV) in 2023, 52.9% of the participants surveyed foresee an increase in the existing polarization in Turkey in the coming years. Conversely, the proportion of those believing in a decrease in polarization remains limited, standing at only 14.5% (SODEV, 2023). According to the 2023 Reuters Institute Digital News Report, online news consumption in Turkey stands at 75%, a seemingly high figure; however, this indicates an 8% decline compared to the previous year. The report notes that globally in 2017, 63% of people showed “high” or “intense” interest in news, a figure that dropped to 48% in 2023. Researchers in the report emphasize that the decline is more pronounced in countries where there is high levels of polarization. However, more than half of the participants (56%) express concern about distinguishing between real and fake news online when it comes to news topics, a two-point increase from the previous year. The concern is higher among those who use social media platforms as a news source (64%) compared to those who do not use them (50%). Countries with high levels of concern about misinformation are highlighted as places where social media usage rates are also high (Newman et al., 2023).

The Russia–Ukraine war not only remains confined within geographical borders but also significantly impacts the digital realm, sparking extensive debates via social media. The war creates an environment where fake posts spread rapidly across social media platforms, potentially deepening polarization.

While social media may not be the primary driving force behind polarization, it does provide a conducive environment for exacerbating such tendencies. Social media facilitates polarization among individuals, while Kitchens et al. (2020) emphasize how social media algorithms increase interaction with like-minded individuals, limiting exposure to different perspectives and encourage the adoption of more extreme ideological positions. Thus, in situations like the Russia–Ukraine war, these tendencies become even more pronounced.

Context: Russia–Ukraine war and Turkish social media

The 2022 Russia–Ukraine war began on February 24, 2022 with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This attack marked the culmination of long-standing tensions between the two countries. The war that started with Russia’s military intervention in Ukraine has turned into an international crisis. Russia’s invasion was the beginning of a very difficult process for the Ukrainian state in humanitarian terms. Moreover, international trade and economy are affected by this war. On the other hand, this war has brought an international agenda and attracted the attention of the world powers to this geography. Many countries condemned Russia’s aggressive behavior and expressed their support for Ukraine. Throughout this process, the international community and the media, including social media platforms, have closely followed the development of the war.

In contexts of crisis and conflict, raw and processed information plays a significant role in mobilizing masses, fostering collective struggle motivation, and operating mechanisms of public diplomacy. The examination of disseminated false posts on social media platforms can provide insights, especially during times of crisis and conflict, into the circulation of information. The anonymity of those responsible for disseminating false information can be preserved after it goes viral. However, as demonstrated in this study, the analysis of fake posts emerging from Turkish social media spheres regarding the Russia–Ukraine war reveals that during crises or wartime situations, a distinctive social media discourse is formed when these posts are reproduced, distorted (in conjunction with disinformation), and shared intentionally or unintentionally, alongside personal beliefs and opinions.

Some recent studies on the Russia–Ukraine war, which has global implications, similarly focus on the interpretation of social media posts in the context of the Russia–Ukraine war. Shevchenko (2022) examines the political discourse on American social media, addressing the use and configurations of semiotic resources. Canals (2022) explored the meanings and functions of false images in the war, arguing that falsification arises from various factors. Primig et al. (2023) investigated how TikTok spreads information about the war and its impact on representation. Poepsel et al. (2024) analyzed the propaganda role of humor shared on Twitter by the @Ukraine account, suggesting that humor can strengthen national unity and increase support from the “west”. They examined over 100 memes from 2016 to 2023, suggesting that humor can strengthen national unity and increase support from the “west”.

In addition to the importance of studies addressing the effects of war on social media, understanding the themes of fake social media posts during war, as this study explores, can provide insights into the discourses through which fake posts on social media are polarized and how fake posts are shaped in the context of war. Furthermore, Turkey’s role in the region and its diplomatic relations with both Russia and Ukraine make it a significant agenda item for Turkish social media. As a result of the crisis between Russia and Ukraine, fluctuations have emerged between Russia and Europe in the fields of politics, security and energy. In light of these tensions, Turkey, from the beginning of the process, has produced the policy that it is an ideal candidate to assume the role of mediator for both Ukraine and Russia as a result of the balance policy it wants to establish between the two countries (Lesage et al., 2022; Butler, 2024). Turkey’s attitude of pursuing a policy that would not damage its relations with both countries was also shaped around the dominant political discourse in which Turkey tried to position itself politically. In addition to the political, economic and cultural manifestations of the war, the twofold, mediating policy of the Turkish government contributed to a social media pattern shaped by fake social media posts based on easily divisive discourses, as this study attempts to examine. In these contents, it is seen that one side of the fake social media contents about the war is about legitimizing and protecting Russia’s position in the war. On the other hand, in the fake news about the Ukrainian side, the economic, social and humanitarian collapse and destruction of the country due to the war is revealed and Russia is shown as the main cause of this situation (Babacan and Tam, 2022).

This is also related to how misinformation/disinformation is shaped by domestic and foreign issues in the context of evolving political events. In this regard, numerous studies conducted in Turkey explored the Russia–Ukraine War. Some of these studies have approached the war from the perspective of international relations (Öztürk, 2023). Among these inquiries are studies that assess the war’s impact based on user comments on social media platforms, such as Çiçekdağı (2022) examination of how the war affects tourism in Turkey through online commentary. Fidan, Lokmanoglu (2023) explores the concept of digital embargo in the context of the Russia–Ukraine war, emphasizing the impact of social media company restrictions on Russia. They underscore the significance of this concept, advocating for its better acknowledgment in future similar scenarios. Concurrently, Geyik and Yavuz (2023) scrutinize digital diplomacy’s role during the Russia–Ukraine War, highlighting Twitter’s important role in garnering international support. By analyzing the communication strategies of the Russian and Ukrainian Embassies in Ankara, the study reveals Ukraine’s superior performance in this regard. Babacan and Tam (2022) focus on the proliferation of fake news during the initial stages of the Russia–Ukraine war, emphasizing the role of social media platforms in facilitating information warfare. Their analysis of 125 fake content via Turkish Fact-Checking platforms unveils the prevalence and dissemination patterns of such content across various media tools. In another study, Gürocak (2023) analyzes the polarization caused by the Russia–Ukraine war on social media through Ekşisözlük, a prominent social media platform in Turkey. Furthermore, there are studies that have examined propaganda activities during the war, exploring the official news agencies of the involved nations (Köksoy and Kavoğlu, 2023) or the communications of Turkish embassies (Durmuş, 2023). In addition, certain studies have focused on analyzing the ideological underpinnings of language usage in online journalism (Kılıçaslan, 2022) or have explored disinformation and fake news related to the war (Babacan and Tam, 2022; Akyüz and Özkan, 2022; Sığırcı, 2023).

In addition to numerous studies focusing on the dissemination of fake content and misinformation on social media in the context of the Russia–Ukraine war, this study can provide a more specific qualitative context by focusing on and examining fake posts related to the war specifically within the context of Turkish social media, under themes. This context can offer insights into which types of fake social media posts in Turkey have been exposed to since the outbreak of the war. In addition, analyzing fake posts in the context of the Russia–Ukraine war can outline a landscape for identifying concerning areas, revealing the polarized discourses upon which these fake posts are built, and informing the development of strategies to prevent the spread of false information.

Materials and methods

In this study, we aim to first identify the main themes of fake posts about the war in Ukraine that have spread on social media in Turkey and then analyze them through multimodal discourse analysis. As a result of this analysis, we aim to provide data on the forms of fake social media posts which are one of the reflections of the Russian-Ukraine war on Turkish social media. In this context, the data collection process of the study is based on the verifications conducted by Teyit, Doğruluk Payı, Doğrula and Malumatfuruş platforms operating in Turkey, on fake social media posts circulating on Turkish social media related to the Russia–Ukraine war. These platforms have been monitoring and verifying war-related misinformation/disinformation on social media since the early days of the war. Three of them, Teyit.Org, Doğrula and Doğruluk Payı, are members of the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN). All platforms declare that they follow IFCN’s methodological principles. The study encompasses data from February 23, 2022, to June 10, 2023. In this context, a total of 243 samples were initially identified for analysis. However, 204 of these were cross-validated by both platforms and verified to be false, constituting the final sample of the study. Searches were conducted on these platforms using relevant Turkish keywords such as “Rusya-Ukrayna Savaşı “, “Ukrayna”, “Rusya” and “Rusya-Ukrayna çatışması”.

Fact-checking platforms play an important role in identifying and verifying fake content. Especially those belonging to international fact-checking networks, these platforms aim to analyze information from various sources to reach reliable and accurate data. In our study, we examined fake posts circulating on Turkish social media related to the Russia–Ukraine war and obtained these fake contents from fact-checking platforms. The methodologies and memberships in international networks of fact-checking platforms enhance the reliability and accuracy of the data they provide. Additionally, since there is a risk of subjective bias in the process of identifying fake content, the objective methods and expert analyses provided by fact-checking platforms have increased the credibility of our research.

In this study, we utilize a Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis (MCDA), which draws on Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). This approach assumes that linguistic and visual choices reveal the broader discourses expressed in texts (Kress, Van Leeuwen (2020)) like CDA, MCDA aims to reveal what kinds of social power relations, inequalities, both explicit and implicit, are maintained, produced or legitimized in texts (van Dijk, 2015). Furthermore, digital media and social media are multimodal, taking advantage of new technological possibilities, and with this, MCDA is important in revealing how the modes play different roles at the same time or what the use of these modes together means discursively and how they work together to express discourses. In this respect, in our study, we examine the multiple modes of text and images together when analyzing fake social media posts. We also examine other elements accompanying the post from a critical discourse perspective.

In our study, we believe that an analysis approaching from the multimodality perspective of Kress, Van Leeuwen (2020), supported by critical discourse analysis, could be impactful. However, we also contend that an analysis based on visuals can be applied in the analysis of video and text-based fake shares. As Machin and Mayr (2023), also state, meaning is produced not only through language but also through other semiotic modes. Kress, Van Leeuwen (2020) defined multimodality as a characteristic of texts that employ multiple semiotic codes, including words and images. With the significant proliferation of social media platforms as news and information sources, we consider multimodal discourse analysis important as it enables researchers to examine text, visuals, and hypertext independently and together. Building upon this, multimodal discourse analysis places a central emphasis on the representational metafunction. By employing this metafunction, the analysis of fake social media posts becomes feasible as we investigate how language serves the function of representation. In this stage, the focus is on examining the meaning conveyed in the text. Symbols, visuals, and other semiotic elements in the text are analyzed in terms of how they are organized and used. The main focus here is to understand how the text represents the world and conveys messages to the reader. In the scope of this research, we embraced the ‘representational metafunction’ to deconstruct fake content circulating on social media. Our approach involved a thorough exploration of the structural and semantic aspects of fake posts, all viewed through the lens of language’s representational function. Furthermore, we utilized this framework to examine the contextual dimensions of fake content, unraveling its underlying themes. On the other hand, compositional and interactive functions contribute to the examination of the performative functions of the content, helping to understand its role and impact by interpreting the intended messages conveyed through visual elements and textual components (Paltridge, 2021; O’Halloran, 2021). The interactive metafunction denotes the dynamic relationship between the producer of the message and the recipients. While evaluating these posts, we considered the interactive function as they reflect the interaction and relationships between the sender and the recipients. The interaction between the sender and the recipients can be discerned through the language, tone, and content choices in the posts. In addition, the purpose of creating emotional impact on the viewers through visual elements and texts in the posts was also regarded as part of the interactive function. In addition, while examining text and other modes, we utilized the compositional function. At this stage, the structural features and arrangement within the text are examined. How visual and verbal elements in the text are arranged influences its flow and organization. This stage is used to understand how the text is organized and what structural features it carries.

The coding process was conducted to identify themes within fake social media posts. Initially, researchers examined the fake posts and conducted a preliminary review to identify common features and recurring themes among them. After identifying the main content and themes, we delved deeper into the forms and functions of various themes. (War reporting n = 71, ideological misrepresentation n = 55, humor n = 31, hate speech n = 23, conspiracy theories n = 24). Subsequently, a meaningful coding scheme was developed based on these identified themes. The coding scheme included categories used to identify different types of content present in fake posts. Initially, coders examined the visual elements present in the fake social media content. These visual elements included images, videos, and graphics. Coders assessed the messages conveyed by these visual elements and the use of visual symbols. Subsequently, our focus shifted towards uncovering the underlying meaning of these contents by re-evaluating the main content across all modalities, encompassing visual, textual, and, if applicable, other elements.

This was followed by the coders examined the textual elements within the content. These textual elements encompassed the language used, the structure of the text, and the meanings conveyed by the words employed. Coders evaluated how the textual elements supported the discourse in the content and conveyed specific themes. Coders integrated the visual and textual elements to ensure the coherence of the content. They analyzed the relationships between visual and textual elements and how they complemented each other. For instance, coders assessed how the textual components alongside visual elements were used to convey the intended message.

Coders analyzed the identified themes and discourse by considering both visual and textual elements. They determined the themes addressed in the content and the discourse conveyed. To analyze the forms, we elucidated how different modes in fake posts—visual elements (Kress, 2012)—converged to construct the discourse. Given that the intended meaning of an image is often reinforced with verbal explanation, we also paid particular attention to the text accompanying the visual content. Coders limited the modalities of these contents based on Facebook, Twitter, and TikTok, categorizing them into video, text, image, and hashtag. The modalities in each sample were individually noted, and then their coherence, when combined, was examined. For instance, in a Facebook post, the image and text were noted separately, but their combined meaning and theme were considered during analysis. At the third level of analysis, by amalgamating the analyses of content and form, we presented the images in both their immediate and broader discursive contexts. This process allowed for a comprehensive understanding of the content, as examining both visual and textual elements provided deeper insights into the conveyed themes and discourse.

The coding process was an iterative one aimed at establishing consensus among researchers. Researchers independently coded the same dataset using the established coding scheme. In order to analyze social media posts, two coders followed the methodological steps of emergent coding in content analysis (Franzosi, 2017; Krippendorff, 2018; Neuendorf, 2018). To establish a reliable codebook, two coders examined the sample data, and the coding was measured using Krippendorff’s Alpha. Freelon’s online tool was utilized to measure inter-coder reliability, with the results k ≈ 0. 76 indicating a efficient level of acceptability. Afterward, the coding results were compared, and any discrepancies were discussed. Upon resolving disagreements, the coding process was repeated and refined until a consensus was reached on the results. The coding process employed a qualitative approach to identify and analyze themes. The coders, considering the unique nature of the cases under study and the unsuitability of borrowing a codebook from previous research for this study’s objectives, opted not to employ deductive coding. Independently, the coders examined a sample of social media data and subsequently engaged in several discussions to identify the categories that should be employed inductively. After several deliberations, the coders reached consensus on identifying the main themes. The resulting analyses provided us with data by examining the themes in which fake post is shaped on Turkish social media in the context of the Russia–Ukraine war, and it revealed clues for us to interpret them within the discursive context.

Findings and analysis

Theme 1: war reporting

(Re)porting the war

Fake posts within this theme consistently exhibit a bias toward war-related events on social media, transforming the platform into a space where users actively generate news-like content. Users or groups without direct news affiliations leverage news-like discourse, employing tactics like “clickbait” and manipulated images to swiftly disseminate content through likes and shares.

The analyzed fake posts commonly employ image manipulation, strategically placing photos and videos out of context to construct misleading narratives about war-related events. Accompanied by written text, this tactic establishes synthetic and linguistic contexts aligned with the desired narrative. As noted by Barthes (2003), images are polysemic, and text functions as an “ironing” tool, eliminating ambiguity and directing viewer interpretation. In essence, these fabricated posts aim not only to report events but also to create a semblance of reality, utilizing the visual impact of manipulated images and the persuasive power of accompanying textual elements. The amalgamation of visual and linguistic elements enhances post virality and has the potential to attract a sizable social media audience with engaging content.

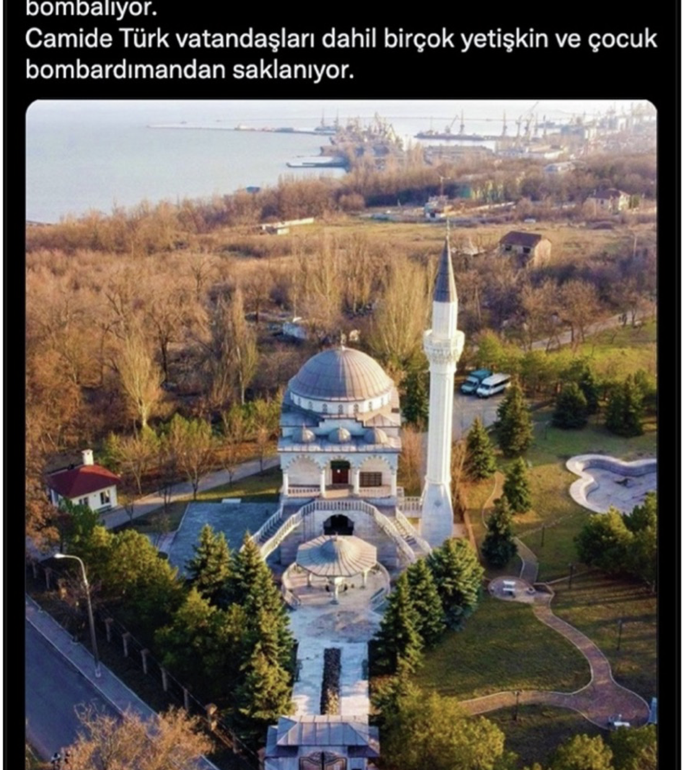

In Fig. 1, the fake post features an image of a mosque taken from a high angle, accompanied with the hashtag #Mariaupol and the Ukrainian flag emoji. Upon textual analysis of the post, it can be seen as an example of a text reconstructed using fragmented contexts previously discussed. The post includes the statement, “Right now, the Russian (indicated as an emoji) army is bombing the “Magnificent Mosque” built in memory of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and Hürrem Sultan. Many adults and children, including Turkish citizens, are taking refuge in the mosque from the bombardment”.

Russia Allegedly Bombed a Mosque in Mariupol, Ukraine From Malumatfuruş.Org Accessed on https://www.malumatfurus.org/rusya-ukraynada-cami-vurdu/.

Another rhetorical context in this example is the linguistic elements based on a historical narrative. The mosque that is claimed to be bombed is said to have been built in memory of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and Hürrem Sultan. Again, this rhetorical structure takes shape through a provocative statement that indirectly calls on the Turks to act. In another form of communication between visual and linguistic modes, they appear to complement each other. When we look at the structure of the language, the phrase “right now” creates a narrative that is shaped from the perspective of a witness. This phrase can be considered as an expression used to reinforce the context of the statement. As noted above, while the visual and textual elements in the post seem to complement each other semantically and semiotically, the news does not contain any information about the situation it claims.

In this context, the analyzed fake posts are primarily based on speculations and claims from the early stages of the war. Social media content warning that the war could “break out at any moment” and affect Turkey often utilizes historical and cultural contexts. For example, a different example features an image of the Russian Orthodox Church in Istanbul, emphasizing the narrative of “historical proximity” to defend Turkey’s support for Russia. In addition, in another example, images from the Chechen War and phrases such as “Russian killers are targeting civilian Chechen families” reinforce the narrative that Turkey should side with Ukraine “against Russian killers”. These examples can show how the historical background is intertwined with war-related narratives in fake posts and can reveal the functions of establishing duality through these historical narratives.

War is started, “Ukraine is alone”

The content we have gathered under the theme of “war reporting”, which began to spread on social media with claims that “the war has started”, is more focused on constructing or, in other words, reproducing the narrative of the war on social media, rather than informing about the actual commencement of the war. During our research, the dominant sub-theme we most frequently encountered under this theme is the narrative of “Ukraine’s isolation” which asserts that Ukraine is being abandoned by world powers. While these posts are presented as “breaking news” regarding the war or frontline developments, they are embellished with personal opinions and ideological perspectives, thereby blurring the lines for obtaining accurate information about the war.

When examining the content that shapes this theme, it is observed that fake posts combine disjointed contexts with visuals and baseless claims. Analyzing the fake posts created around these new contexts, we observe a juxtaposition of textual or visual representations of events derived from two or three different contexts or past occurrences, creating a contrast as exemplified in the first instance. These fake social media posts, shaped by the notion that there will be significant consequences due to the “start of the war” and the “abandonment of Ukraine” are created by combining texts severed from their contexts with fabricated images. Under our first theme “war reporting” we encountered this type of fake post that distorts news or events related to the war.

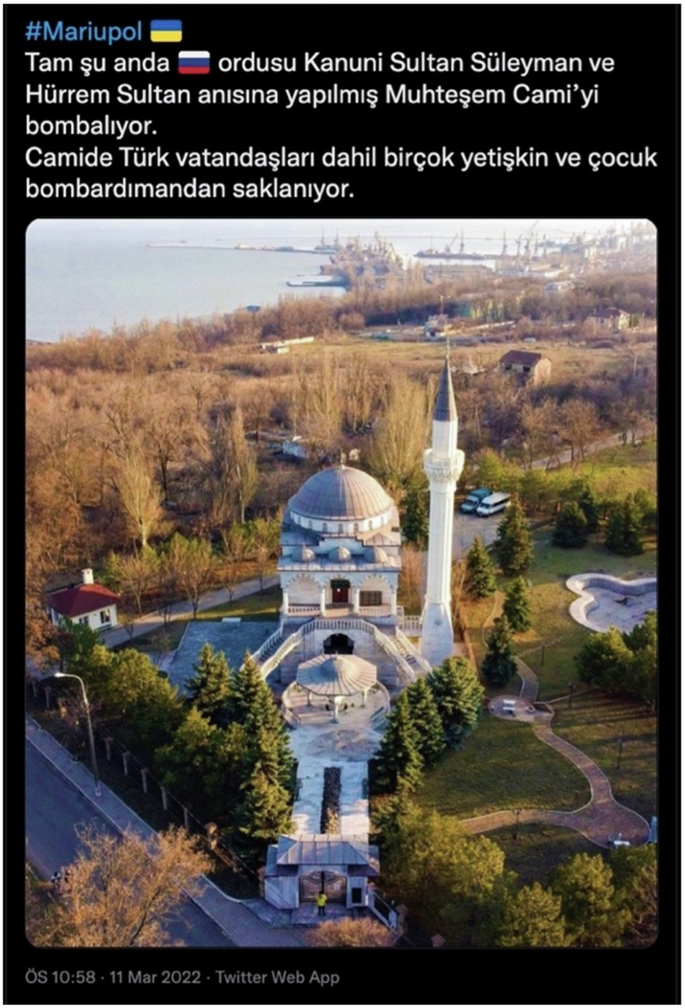

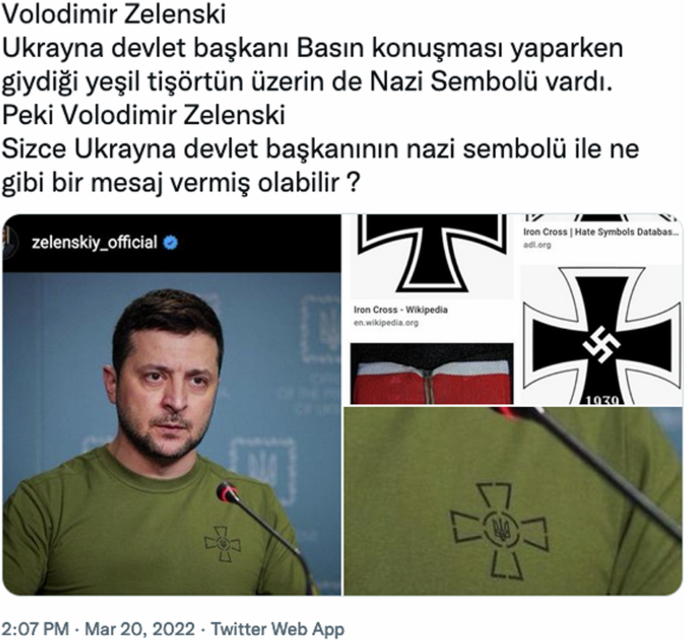

One of the most appropriate examples related to the topic we have discussed above is the fake post we deliberated on in Fig. 2. As seen in Fig. 2, this narrative is now shaped through the premise of “NATO’s necessity to intervene in the war in Ukraine.” In fake post, a night photograph depicting a beam of light has been used. This image is portrayed as explosions in Kharkiv and Kiev. The accompanying text states, “WAR HAS BEGUN. Violent explosions are happening in Kharkiv, Kiev, and many other cities. Europe and the US have abandoned Ukraine. Russia and Putin are doing whatever they want. NATO is urgently intervening. #Putin #war #Ukraine #Thursday #Kiev”.

“WAR IS STARTED” from Doğrula.Org Accessed on https://www.dogrula.org/dogrulamalar/kharkiv-rusya-ukrayna-catismasina-ait-video-iddiasi/.

The fake post in Fig. 3 is based on the narrative of “political isolation” and “Ukraine resists”. In the image, two children are seen looking at the soldiers on armored vehicles, with their backs turned and holding hands. The text accompanying the image reads “Even children in Ukraine support the army, Ukraine resists; “18–15 year-old men” continue to join the army”.

Ukrainian Childs From Doğruluk Payı Accessed on https://www.dogrulukpayi.com/dogruluk-kontrolu/ukrayna-askerlerini-selamlayan-cocuklari-gosteren-fotograf-guncel-mi.

The statement “even children in Ukraine support the army” is supported by the image of a child giving the military salute. The rhetoric of this post reveals an implicit message of Ukraine being left alone. The phrases “Ukraine resists” and “even children” reinforce the textually implied meaning.

Theme 2: ideological misrepresentation

Ideologic dilemma: “Nazi-Ukrainians” vs “Nazi Russians”

One of the key issues in the critical approach is the topic of ideology, which is based on the assumption that the media is a powerful ideological force. This idea maintains that the media is one of the most important tools for spreading ideology, which is considered as a unifying and integrating power in society. When these thoughts are taken into consideration, the view that the media functions as an extension of the powerful interest groups in society, especially at an ideological level, and plays an effective role in the reproduction of dominant ideology (van Dijk, 1997, 2015) and maintenance of the control system is prevalent (Shoemaker and Reese, 2002, p. 127).

On the other hand, language is the material form of ideology and is encompassed by ideology (Fairclough, 2003, p. 158). In short, ideology is the process related to information, dialog, narrative, statement style, argumentation, power, and the transformation of power into action through linguistic practices. Discourse is regulated by the internal rules of speech, narrative and speaking actions. The internal rules of discourse form discourse regimes, and discourse is the result of organized and selected discourses coming together (Sözen, 2017, p. 20). Kress, Van Leeuwen (2020) argue that when analyzing discourse as ideological, it is important to consider how visual images as a form of representation present interpretations of reality rather than neutral reflections.

From this point of view, the second theme of the study revolves around the ideological misrepresentations and the polarization constructed through these misrepresentations in Turkish social media. It has been observed that historical ideological representations and symbols are widely emphasized in fake content spread on the platform. It has been revealed that both pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian fake post disseminated through social media platforms do not hesitate to incorporate symbols and historical remnants of Nazism when constructing ideological representations. In addition, within the context of this theme, numerous posts have been observed circulating to reinforce the stereotype that Ukraine has a neo-Nazi-rooted army. In these contents, the narrative emphasizes that Ukrainian nationalist movements attack Russia, that these groups hold views against Russia filled with anger and hatred, and that they manipulate the Ukrainian people.

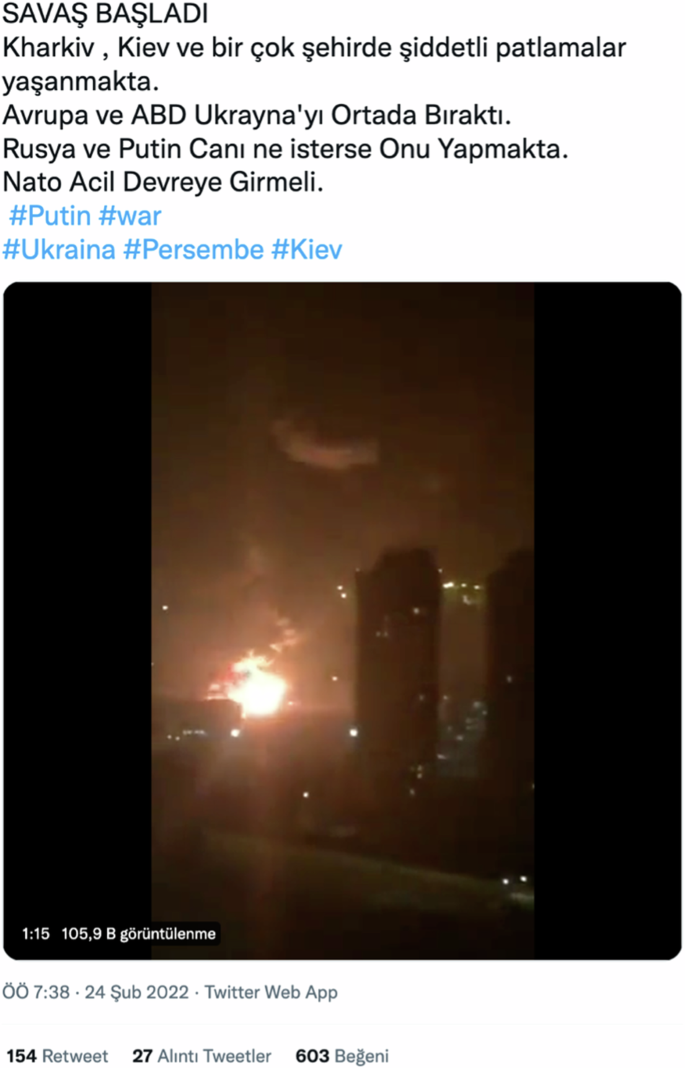

In Fig. 4, within the analyzed content, it is observed that a misleading image associates President Zelensky’s sweatshirt, bearing the logo of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, with a Nazi symbol during a speech. This deceptive post includes three different visuals: close-ups of Zelensky’s appearance and the logo on his sweatshirt. In addition, a screenshot displaying Google search results for Nazi symbols has been added as supporting evidence to this deceptive content. The accompanying text in this post poses the question, “What message can Ukraine’s President convey with a Nazi symbol?”. In this context, the Ukrainian military is portrayed not as the national armed forces but as elements aligned with nationalist neo-Nazi ideologies. It appears that this portrayal aims to evoke destructive, monstrous, immoral, and cruel connotations reminiscent of historical ideologies. When examined under this theme, these deceptive contents seem to be designed to provoke the audience’s feelings of defense and judgment through the use of ideological symbols.

Nazi symbol on Zelenksy’s Sweatshirt From Teyit.Org Accessed on https://teyit.org/analiz-zelenskinin-nazi-sembolu-demir-hacli-tisort-giydigini-gosterdigi-iddia-edilen-fotograf.

In Fig. 5, President Putin is portrayed on a fictitious cover of Time magazine. The accompanying text reads, “The cover of Time magazine… The direction this is going is clear to see…”. Upon closer examination of the image, it becomes apparent that Putin’s photograph has been digitally manipulated alongside a photograph of Hitler. The black-and-white image of Hitler serves as the background, creating a visual narrative in conjunction with Putin’s photograph. The cover’s headline reads, “The Return of History, How Putin Shattered Europe’s Dreams.” Putin is unmistakably being likened to Hitler, with the images manipulated to align Hitler’s mustache with Putin’s face. Furthermore, the text, “The direction this is going is clear to see…,” suggests the establishment of a narrative that Putin is following in “Hitler’s historical footsteps” and poses a threat to Europe. Upon an examination of Figs. 4 and 5, it becomes evident that two contrasting narratives are being constructed, with Hitler imagery being used to portray “Nazi Ukraine” as the remnants of Hitler’s militia forces and “Putin” as a Hitler-like figure.

Fake Time Magazine Cover From Teyit. Org Accessed on https://teyit.org/analiz-time-dergisinin-putini-adolf-hitlere-benzeten-kapak-hazirladigi-iddiasi.

Theme 3: humor

Disjointed humor blurs the reality of the war

The use of humor elements in fake posts related to the Russia–Ukraine War, disseminated on social media in Turkey, is also an important issue in terms of our analysis. The use of humor elements can make it more difficult for social media users to recognize that these posts are not real.

In this context, the analysis of such content can also help us understand how humorous elements are constructed within fake posts. It would be misleading to consider humor elements separately from ideological representations; Given their incorporation of personal perspectives and convictions, humor elements frequently intertwine with scenarios such as war news or breaking news. They can be easily guided by individual points of view and supported by ideological views. In addition, as researchers uncover a rise in political trolling across social media platforms, they also note that negative posts elicit significantly more comments compared to positive ones (Rathje et al., 2021). This trend is to be expected, considering that these comments occur within environments that fuel polarization. Negative posts “attract more angry or laughing-emoji reactions on Facebook than the positive receive hearts or thumbs ups” (Kleinman, 2021). Additionally, “social media posts are twice as likely to go viral if they are negative about politicians they oppose rather than positive about those they support” (Kleinman, 2021).

In this context, we have also included fake posts that has been experimentally combined with humorous elements and detached from its original context in our analysis. For example, in Fig. 6, it is depicted that a Russian tank was destroyed by a Turkish-made Armed Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UCAV). We observe that in this fake post, a decontextualized video is used as an enhancing modality accompanying a humorous element. In Fig. 6, the posts shared by a humor magazine named “Misvak” from its official Twitter (X) account combines the text “Bayraktar, SIHA TB2 mistreated Russian convoy” with an unspecified source 9-second video. The video shows an exploding tank, but it appears unclear when and where the video was recorded and which event it is related to. Furthermore, the framing of this share in a “humorous” and “trolling” language blurs events and situations that should be taken seriously in the context of war, making them subjects of humor.

A Turkish Humor Magazine Misvak: “Bayraktar, SIHA TB2 mistreated Russian convoy!” From Teyit.Org Accessed on https://teyit.org/analiz-videonun-siha-tb2lerin-rus-konvoyuna-saldirisini-gosterdigi-iddiasi.

Fake post combined with elements of humor and political trolling featuring content that is disjointed and unrelated, can escalate into ideological and political debates on social media. Some of the fake posts we have examined are based on fake humor elements imitating events claimed to have occurred during the alleged war.

Theme 4: hate speech

“Foreign powers” and “political pawn” Zelensky versus “soldier” Zelensky

The common theme in pro-Russian fake posts about Zelensky on social media revolves around his leadership image. However, their reflections on Turkish social media are twofold. Pro-Russian fake posts targets Zelensky by combining elements of hatred and hostility, focusing on his life before his political career. On the other hand, pro-Ukrainian fake post portrays Zelensky as someone who stands by the people, describing him as a “soldier” and a “real man”. In this section, we preferred to include these two examples to illustrate this polarization through two striking instances. It appears that, drawing from hate speech, other fake posts examined in this theme attack Zelensky’s leadership image.

Within the scope of the study, we encountered fake posts that portrayed President Zelensky as a Fig. at the behest of the “West.” This is often accompanied by the narrative of “foreign powers” and fake posts under this theme often includes xenophobia and LGBT hostility.

A striking example of this theme is the portrayal of “LGBT rights” as a tool allegedly used by the “Western world” to weaken and destabilize Russia. The LGBT community is systematically constructed as a foreign hostile element closely associated with the “West”. In particular, the narrative built around the concept of “foreign powers” is repeated through hate speech against the LGBT community and President Zelensky’s leadership persona.

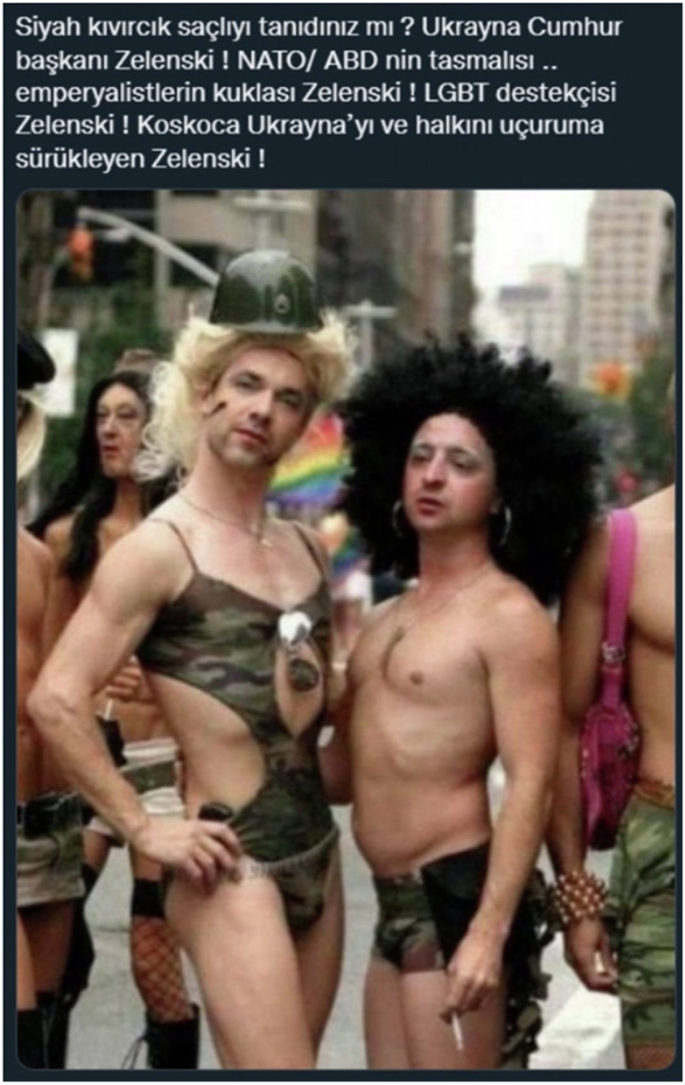

Figure 7, in particular, presents a manipulated image of Zelensky towards a leadership image that is explicitly associated with LGBT hostility. The text accompanying Fig. 7 serves as a powerful tool to propagate this biased narrative: “Have you met the one with the black curly hair? President Zelensky of Ukraine! NATO is the poodle of the United States. Zelensky is a puppet of the imperialists! Zelensky is a supporter of LGBT! Zelensky is leading Ukraine and its people into the abyss!”. The use of manipulated images and derogatory language in this post perpetuates the narrative that portrays Zelensky and the LGBT community as “agents of Western hegemony”. In this context, this fake post uses fake images and text to reinforce a degrading representation of Zelensky’s leadership image and narrative of his supposed alignment with “Western interests”.

Fake post targeting Zelensky through hate speech against LGBTI identity From Doğruluk Payı Accessed on https://www.dogrulukpayi.com/dogruluk-kontrolu/fotograf-ukrayna-cumhurbaskani-volodimir-zelenski-yi-onur-yuruyusu-nde-mi-gosteriyor.

The narrative of “foreign powers” that emerges in pro-Ukrainian fake post is utilized to denote nation-states and international organizations perceived covertly as adversaries, aiming to undermine Ukraine’s economic and political development. In this sense, the “foreign powers” narrative includes “hostile foreign states” that secretly aim to harm the country. For instance, another fake post analyzed claims that Ukraine and Turkey should join forces against “external forces” and includes a photo of Zelensky in the Ukrainian parliament and a fabricated quote calling for unity against “common external enemies”.

In contrast to the fake post analyzed above, the pro-Ukrainian fake content includes images supporting Ukraine and promoting President Zelensky. Most of these posts emphasize Zelensky’s compassionate side and characterize him as a soldier.

In Fig. 8, a photo of Zelensky wearing a helmet, body armor, and military uniform gained wide circulation on social media at the beginning of the war. Accompanied by fake posts, the image falsely claimed that Zelensky himself was on the front line, fighting alongside soldiers in the line of fire. This image appeared on social media in many different contexts. This photo, which can be seen as an example of a photo being taken out of its context and shared in different contexts, is placed in a context where the image of Zelensky’s leadership is reproduced as “a soldier fighting alongside his people and taking part in the front line”.

The President of Ukraine is on the front lines. From Doğruluk Payı Accessed on https://www.dogrulukpayi.com/dogruluk-kontrolu/fotograf-ukrayna-devlet-baskani-zelenski-yi-cephede-mi-gosteriyor.

Theme 5: conspiracy theories

Panic in the deep state! Rothschild said: “we are done!”

Conspiracy theories refer to assertions and stories that seek to attribute the causes of various social occurrences to the covert designs of two or more individuals or entities (Coady, 2006). It is important to note that from an epistemological perspective, these conspiracy theories should be regarded only as “hypotheses.” In this sense, the term “theory” does not carry any epistemological connotations (Coady, 2006, p. 2; Byford, 2011, p. 23). Bali (2016) states that the concept of “foreign powers” as a classic figure in conspiracy theories points to the desire to find a target to blame for the negativities in society. Today, it is constantly kept on the agenda by various media organs and naturally resonates in wide circles as a discourse that feeds such conspiracy narratives. This avoidance of confronting the actual realities, and instead blaming evil external forces without evidence, represents a means of evading responsibility through self-reflection.

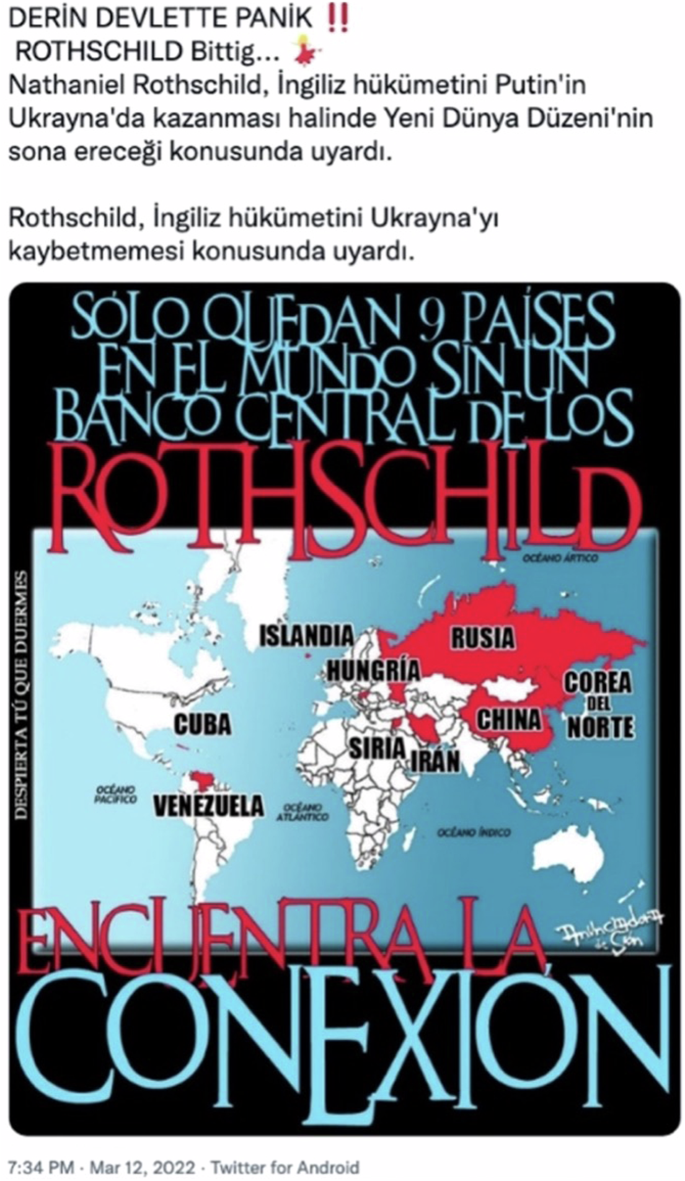

In the fake posts, we analyzed, we encountered a large number of fake content that are based on conspiracy theories. In this sense, we saw that conspiracy theories emerged in Turkish social media in the context of the Russia–Ukraine war in two intertwined ways. The first conspiracy theory is that the war was initiated by “external and secret” forces, commonly referred to as “foreign powers”. The second conspiracy theory context is based on fake post that the war is not real and that “foreign powers” are digitally staging the war to build a “new world order” and that the international media is playing a role in this staged scenario. In the fake post shown in Fig. 9, the conspiracy theory about the “new world order” is reproduced in a new context through the Russia–Ukraine war. The text in the fake post includes the phrases “DEEP STATE IN PANIC: Rothschild warns…” and “Nathaniel Rothschild warned the British government that if Putin wins in Ukraine, the ‘New World Order’ will end”. In addition, the image accompanying the fake post reads in Spanish, “There are only 9 countries left in the world that do not have a Rothschild Central Bank”.

“DEEP STATE IN PANIC” From Doğruluk Payı Accessed on https://www.dogrulukpayi.com/dogruluk-kontrolu/nathaniel-rothschild-ukrayna-nin-rusya-ya-karsi-kaybetmesi-konusunda-bir-aciklama-yapti-mi.

Another example of a “fake war” conspiracy theory is the fake post shown in Fig. 10, which includes 5 s of video. In this short video, people are seen fleeing in a square, accompanied by the text: “A very convincing professional film was shot in the center of Kiev.

Video Supposedly Depicting Staged Escape of Ukrainians from the Russian Army From Malumatfuruş. Org Accessed on https://www.malumatfurus.org/ukrayna-sahte-video/.

Supposedly, Ukrainian people are fleeing the attack of the Russian army. Similar movies were shot for Syria as well. There was also an intervention in Iraq under the pretext of weapons of mass destruction!” The fake posts we are examining claims that the war is fake and fabricated, and that previous fake wars were orchestrated by “foreign powers.” The video shown in the fake post features people running in a square. This 5-s video is used to reinforce the message that the war is staged with fake footage. Hybrid conspiracy theories, which emerge as a result of the combination of personal views and opinions with the narratives underlying conspiracy theories, can be considered as one of the most dangerous content for social media. Similar to this instance, conspiracy theories lacking a scientific foundation can be readily disseminated and proliferated due to content structures that are replicable and shareable irrespective of context.

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we chose to examine the fake posts circulating on Turkish social media related to the Russia–Ukraine war. To achieve this, we employed a multimodal discourse analysis approach to shed light on the fake social media posts circulating in the Turkish social media context. Multimodal discourse analysis was chosen as one of the most suitable methods for examining the content we collected and used in the study, as it allows for the analysis of multiple materials and the exploration of contextualized meanings through the combined use of text, audio, and video materials. Its perspective on analyzing the discursive constructions of these “anonymized” and often decontextualized and “disembodied” social media posts proved beneficial in uncovering the discourse of these fake social media posts.

The data we examined within the scope of the study shaped the study around five themes, viewing the Russia–Ukraine war through polarization on Turkish social media: (a) war reporting, (b) ideological misrepresentation (c) humor, (d) hate speech, and (e) conspiracy theories. Our findings showed that fake posts on Turkish social media during the war constructed discourses based on dualities by combining decontextualized textual, visual or video elements from different contexts.

While analyzing the “war reporting” theme, we encountered posts constructed with disjointed and contextless images, videos, and texts. This theme emerged as the most frequently recurring theme in the corpus, for 35%. These fake posts were created by combining at least two different modalities detached from their contexts, aiming to strengthen the narratives of war and support their backgrounds. Instead of conveying the real situation of the war or frontline news, these contents reproduced the war through disconnected contexts. In addition, these fake posts often relied on emotional connotations. Beyond simply reporting on the war or providing breaking news updates, we frequently came across a sub-theme based on the notion that “Ukraine is being left alone by other countries against Russia”. This sub-theme went beyond reporting from the war zone and blurred the background of the war with disjointed and contextless images, videos, and texts, relying on the narratives of “Ukraine being left alone by other world countries” and “Turkey should join the war on the side of Ukraine” advocating collective self-defense or preemptive attack against perceived enemies, which could be supported by atrocity-risk contexts (Rio, 2021) through narratives generated via fake posts. As demonstrated by the posts under this theme, fake posts on social media not only serve as an effective platform for spreading direct calls to attack opponents but also for organizing offline collective actions, serving as a significant catalyst in fueling ideologically driven extremist organizations or communities (Wahlström and Törnberg, 2021).

In the study, it was revealed that fake posts examined under the theme of “ideological misrepresentation” (27% of the corpus) feed into polarization through narratives based on ideological patterns and distorted context. As demonstrated with a striking example of the “Nazi narrative”, the fake posts we investigated under the theme of “ideological misrepresentation” were found to be based on contexts fueled by ideological representations and oppositions. These contexts are evident in various polarized forms in pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian fake social media posts.

The spread of alienating or polarizing rhetoric normalizes political opponents as unreliable enemies or even existential threats. Being subjected to such intense and persistent alienating discourse legitimizes marginalization, denial of rights, and sometimes even violence (Rio, 2021). In a supportive context, it was observed that the most recurring discourse under the theme attempts to construct the Russia–Ukraine war through polarizing ideological contexts, mediating its reconstruction on social media with a distorted historical context rather than the current sociopolitical reality of the war.

Moreover, it is known that misinformation weakens social bonds and divides people into increasingly isolated online political communities. This situation indicates that in Turkey, fake social media posts have turned into radicalized expressions based on either incomplete or intentionally misleading information (Asmolov, 2018). Examined in the context of the Russia–Ukraine war, fake social media posts in Turkey have evolved into radical expressions viewing the war from a perspective of “taking sides.” This simplifies the complexities of the war and deepens polarization. Therefore, conscious efforts are needed to understand the polarizing effects of such fake posts and to address them.

When we examine fake posts based on elements of humor (15% of the corpus), we observed that fake posts circulating on Turkish social media regarding the war is often reconstituted with elements of humor, utilizing visuals and text extracted from the contextual framework of war-related news and juxtaposing them in different contexts. The prevalent perception is that these contents may initially appear merely as a form of social media humor. The elements of humor upon which political trolling thrives can serve as a means to deploy misinformation as part of digital harassment campaigns; particularly when effectively utilized as an “ideological weapon” through online manipulations, dissemination of false information, and distractions to steer public opinion, resulting in the creation of online skepticism and chaos (Zelenkauskaite, 2022). It is observed that the reproduction of humor as a polarizing and ideological tool occurs when it is employed to generate division and propagate specific ideological agendas. However, it should not be forgotten that once these fake posts enter circulation, they have the potential to reframe the war through the lens of fake posts on social media. Humor spreads rapidly on social media, and the incorporation of humor elements in such contents during critical processes like war can position these contents as “informative” elements, potentially sidelining real news about the war. We discovered that the elements examined under the theme of humor often rely on political trolling to legitimize the war while producing false and deceptive information.

In social media, as individuals become politically polarized, they may stop following the other side of the debate and surround themselves with opinions similar to their own. Thus, both opinions and the emotions associated with these opinions are shared on these social media platforms, and then both emotions and opinions are returned to their owners through echoes (Eslen-Ziya, 2022). In this way, humor elements can spread their ideological and polarizing contexts by remaining hidden under the guise of humor, and they can transform themselves into polarizing elements through humorous-looking posts by imprisoning them in echo chambers.

We created a theme called “hate speech” (11% of the corpus) because we observed that the fake posts under this theme were mostly hate speech inciting posts that were embodied in attacks on Zelensky’s leadership image. These posts were used to generate discourses about the war through Zelensky’s image by presenting edited images of Zelensky together with other decontextualized images. At this point, these posts based on hate speech needed to be separated more precisely from humor, even though some of them tried to construct themselves as an element of humor. When examining the main linguistic structures identified in fake posts, for instance, the portrayal of Ukrainian President Zelensky emerges as a significant finding. Especially in pro-Russian fake content on Turkish social media, we found that the predominant discourse aims to undermine Zelensky’s reputation and legitimacy by portraying him as a “comedian,” a “political pawn,” and a “puppet of foreign powers.” In addition, as mentioned earlier, the examples analyzed under this theme attempt to rely on elements such as “hostility,” “humiliation,” and “discrediting” in constructing hate speech, while we found that these fake posts are constructed with decontextualized texts and visuals.

The fifth theme, “conspiracy theories” (12% of the corpus) revealed that the analyzed fake posts, particularly under this theme, often consisted of fragmented visuals, videos, and texts. These disjointed fake posts not only hinder the understanding of events but also reproduce the Russia–Ukraine war. It has also been observed that fake posts are intertwined with conspiracy theories. For instance, the role of “foreign powers” in staging events and orchestrating the war has become a “conspiracy-theorized” in Turkish social media. The reconstruction of the war through ‘social media familiar conspiracy theories’ on social media allows for the easy circulation of fake content and news by capitalizing on this anonymity. Additionally, this situation blurs the real boundaries of events. Furthermore, the structure of conspiracy theories, being built upon informative structures to combat skeptics (Hannah, 2021), allows for the easy incorporation of international or national events of significance or crises. This situation is not unique to Turkish social media. As exemplified in our study with the conspiracy theory regarding the Russia–Ukraine war based on the Rothschild family, conspiracy theories continue to circulate anonymously on social media even if events or crises change or are forgotten. It creates what has been termed epistemic distrust, where bias and accusations of conspiracy undermine truth claims, standards of judgment and evidence and replace them with alternative, unsubstantiated narratives. In such a social media atmosphere, polarizing discourses can more easily carve out their paths and spread. “Users tend to aggregate in communities of interest, which causes reinforcement and fosters confirmation bias, segregation, and polarization. This comes at the expense of the quality of the information and leads to the proliferation of biased narratives fomented by unsubstantiated rumors, mistrust, and paranoia” (Del Vicario et al., 2016). While the circulation of conspiracy theories on social media can have a cumulative effect of sabotaging fact-based reporting and narratives, it can also reduce social and epistemological barriers to coercive conspiratorial thinking (Allington, 2021).

Based on the examined themes, this study provides an overview of the intertwined relationship between Turkish social media and the context of the Russia–Ukraine war by analyzing circulating fake social media posts. It depicts a landscape of deceptive and misleading content associated with various different contexts. The study reveals that fake social media posts on Turkish social media are not created independently of distorted ideological patterns and provides insights into the polarizing structure of fake social media posts around the identified themes.

The study demonstrates that since the early days of the war, Turkish social media has become immersed in an atmosphere of polarization through the spread of false social media posts. While this polarization is rooted in ideological misrepresentation, it also manifests itself through narratives based on humor, hate speech, and the reproduction of news related to the war. The situation of social media in Turkey appears to foster this polarization. In addition, we believe that the thematic analysis of reflections on Turkish social media in a crisis with significant global repercussions such as the war between Russia and Ukraine reveals patterns of disinformation and misinformation in Turkish social media.

Finally, the findings of this study contribute to the analysis of themes obtained from the analysis of fake posts on Turkish social media in the context of the Russia–Ukraine war, while also emphasizing the importance of qualitative findings in studies on deceptive and misleading information on social media. In this regard, the research not only fills the gap in the literature regarding the qualitative and discursive aspects of fake posts on Turkish social media related to the war but also holds significance in showcasing the qualitative forms of false information circulating on social media during a war. Therefore, the findings provide a perspective for future research on the importance of qualitative and discursive dimensions of deceptive and misleading information generated in social media posts during a crisis.

Data availability

All images of fake posts used in this study were obtained from websites with the consent of the Fact-Checking platforms used as samples in the study. These data are available at https://teyit.org/2022-ukrayna-rusya-catismasi, https://www.malumatfurus.org/?s=rusya+ukraine, https://www.dogrula.org/?s=rusya+ukraine, https://www.dogrulukpayi.com/arama?term=rusya%20ukrayna.

References

-

Al-Rawi A, Prithipaul D (2023) The public’s appropriation of multimodal discourses of fake news on social media. Commun Rev 26(4):327–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714421.2023.2242070

-

Akyüz SS, Özkan M (2022) Kriz dönemlerinde enformasyon süreçleri: Ukrayna-Rusya savaşında dolaşıma giren sahte haberlerin analizi. Uluslar K ültürel ve Sos Araştırmalar Derg 8(2):66–82

-

Allcott H, Gentzkow M, Yu C (2019) Trends in the diffusion of misinformation on social media. Res Politics 6(2):10. https://doi.org/10.1177/205316801984855

-

Allington D (2021) Conspiracy theories, radicalisation and digital media. Global Network on Extremism and Technology. https://gnetresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/GNETConspiracy-Theories-Radicalisation-Digital-Media.pdf

-

Asmolov G (2018) The disconnective power of disinformation campaigns. J Int Aff 71(1.5):69–76

-

Au CH, Ho KK, Chiu DK (2021) The role of online misinformation and fake news in ideological polarization: Barriers, catalysts, and implications. Inf Syst Front 24(4):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-021-10133-9

-

Aydın Düzgit S (2023) Dünyadaki örnekler ışığında Türkiye’de kutuplaşma. In: Erdoğan E, Carkoğlu A, Moral M (eds) Türkiye siyasetinin sınırları: Siyasal davranış, kurumlar ve kültür. Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları, pp 236–250

-

Babacan K, Tam MS (2022) The information warfare role of social media: fake news in the Russia-Ukraine War. Erciyes İletişim Derg 3:75–92

-

Badawy A, Ferrara E, Lerman K (2018) Analyzing the digital traces of political manipulation: the 2016 Russian interference Twitter campaign. https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.04291

-

Bali RN (2016) Komplo teorileri cehaletin ve antisemitizmin resm-i geçidi. Libra Publishing

-

Barthes R (2003) Rhetoric of the image. In: Wells L (ed) The photography reader. Routledge, pp 114–125

-

Brown É (2021) Regulating the spread of online misinformation. In The Routledge handbook of political epistemology. Routledge, pp. 214-225

-

Brummette J, DiStaso M, Vafeiadis M, Messner M (2018) Read all about it: the politicization of “fake news” on Twitter. Journalism Mass Commun Q 95(2):497–517

-

Bulut E, Yörük E (2017) Mediatized populisms| digital populism: trolls and political polarization of Twitter in Turkey. Int J Commun 11:25

-

Butler MJ (2024) Ripeness obscured: inductive lessons from Türkiye’s (transactional) mediation in the Russia–Ukraine war. Int J Confl Manag 35(1):104–128

-

Byford J (2011) Conspiracy theories: a critical introduction. Springer

-

Canals R (2022) Visual trust: fake images in the Russia‐Ukraine war. Anthropol Today 38(6):4–7

-

Chaudhari DD, Pawar AV (2021) Propaganda analysis in social media: a bibliometric review. Inf Discov Deliv 49(1):57–70

-

Chen A (2017). The fake news fallacy: old fights about radio have lessons for new fights about the internet. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/09/04/the-fake-news-fallacy

-

Coady D (2006) An introduction to the philosophical debate about conspiracy theories. In: Coady D (ed) Conspiracy theories, the philosophical debate. Ashgate Publishing, pp 1–11

-

Çarkoğlu A, Baruh L, Yıldırım K (2014) Press-party parallelism and polarization of news media during an election campaign: the case of the 2011 Turkish elections. Int J Press/Politics 19(3):295–317

-

Çiçekdağı M (2022) Rusya Ukrayna savaşının turizme yansımaları: Twitter yorumları analizi. In: Bozkurt Ö, Hatem HF, Layek A (eds) 15. Uluslararası Güncel Araştırmalarla Sosyal Bilimler Kongresi. Selçuk Üniversitesi. İstanbul, Turkey pp 839–860

-

Del Vicario M, Bessi A, Zollo F, Petroni F, Scala A, Caldarelli G, Stanley HE, Quattrociocchi W (2016) The spreading of misinformation online. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113(3):554–559

-

Derman GS (2021) Perception management in the media. Int J Soc Econ Sci 11(1):64–78

-

Durmuş A (2023) Sosyal medyada propaganda: Rusya-Ukrayna savaşı örneği. AJIT-e: Academic J Inf Technol 14(52):41–69

-

Erdoğan E, Uyan Semerci P (2018) Fanusta diyaloglar: Türkiye’de kutuplaşmanın boyutları. İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Publishing

-

Erdoğan E, Uyan Semerci P (2022). Kutuplaşmayı nasıl aşarız?. İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Göç Çalışmaları Uygulama ve Araştırma Merkezi. https://www.turkuazlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Kutuplasmayi_Nasil_Asariz_acik_erisim.pdf

-

Erdoğan E, Uyan‐Semerci P (2018) Dimensions of polarization in Turkey: summary of key findings. Istanbul Bilgi University Center for Migration Research. https://goc.bilgi.edu.tr/media/uploads/2018/02/06/dimensions‐of‐polarizationshortfindings_DNzdZml.pdf

-

Eslen-Ziya H (2022) Humor and sarcasm: expressions of global warming on Twitter. Hum Soc Sci Commun 9(1):1–8

-

Fairclough N (2003) Dil ve ideoloji (Language and Ideology). In: Çoban B, Özarslan Z (eds) Söylem ve ideoloji: Mitoloji, din, ideoloji (Discourse and Ideology:Mythology, Religion, Ideology) (trans: Ateş N). Su Publishing, pp 155–173

-

Fallis D, Mathiesen K (2019) Fake news is counterfeit news. Inquiry 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2019.1688179

-

Farhall K, Carson A, Wright S, Gibbons A, Lukamto W (2019) Political elites’ use of fake news discourse across communications platforms. Int J Commun 13:23

-

Farkas J, Schou J (2018) Fake news as a floating signifier: hegemony, antagonism and the politics of falsehood. Javn Public 25(3):298–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2018.1463047

-

Fidan M, Lokmanoglu E (2023) Sosyal medya savaşlarında yeni bir kavram: Rusya-Ukrayna savaşı özelinde dijital ambargo. Bilecik Şeyh Edebali Üniversitesi Sos Bilimler Derg 8(1):28–38. https://doi.org/10.33905/bseusbed.1200734

-

Franzosi, R (2017). Content analysis. In: Wodak R, Forchtner B (eds) The Routledge handbook of language and politics. Routledge, pp 153–168

-

Gallagher K, Magid L (2017). Media literacy & fake news. Parent & Educator Guide. ConnectSafely. https://www.connectsafely.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Media-Literacy-Fake-News.pdf

-

García-Guadilla MP, Mallen A (2019) Polarization, participatory democracy, and democratic erosion in Venezuela’s twenty-first century socialism. Ann Am Acad Political Soc Sci 681(1):62–77

-

Geyik K, Yavuz C (2023) Savaş dönemi dijital diplomasi: Ukrayna-Rusya savaşı örneği. Uluslar Sos Bilimler Akad Derg 11:6–33. https://doi.org/10.47994/usbad.1229282

-

Gürocak T (2023) Conflict and polarisation on social media caused by the Russia-Ukraine War: the case of Ekşi Sözlük. Connectist: Istanb Univ J Commun Sci 65:1–32

-

Hannah MN (2021) A conspiracy of data: QAnon, social media, and information visualization. Soc Media Soc 7(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211036064

-

Haq EH, Braud TB, Kwon YK, Hui PH (2020) Enemy at the gate: evolution of Twitter user’s polarization during national crisis. In: Atzmüller M, Coscia M, Missaoui R (eds), 2020 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining, ACM, New York, pp 212–216

-

Khaldarova I, Pantti M (2020) Fake news: the narrative battle over the Ukrainian conflict. In: Allan S, Carter C, Cushion S, Dencik L, Garcia-Blanco I, Harris J, Sambrook R, Wahl-Jorgensen K, Williams (eds) The future of journalism: risks, threats and opportunities. Routledge, pp 228–238

-