Clarice Cliff, “Fantasque Pitcher,” ca. 1930, painted ceramic/Photo: K.A. Letts

I’m embarrassed to admit that until I traveled to Flint, Michigan to see “Making Her Mark,” I had never been to the state’s second-largest art museum. It turns out I have been missing an opportunity. The Flint Institute of Arts is a pleasure and a revelation, a below-the-radar jewel box of art that justified my drive several times over. The exhibition I went to see is of a piece with many of the museum’s strong points, including an abundance of three-dimensional works in clay and glass.

“Making Her Mark,” on view now until September 28, and curated by FIA director Sarah Kohn, spotlights outstanding ceramic works by contemporary women artists working in clay. The twenty-five one-of-a-kind ceramic artworks on display are mostly from the contemporary fine art studio movement that grew out of the more utilitarian china production industry of the late-nineteenth century. Many are gifts from the collection of Dr. Robert and Deanna Harris Burger, who, since 2005, have donated nearly 300 ceramic works to the museum.

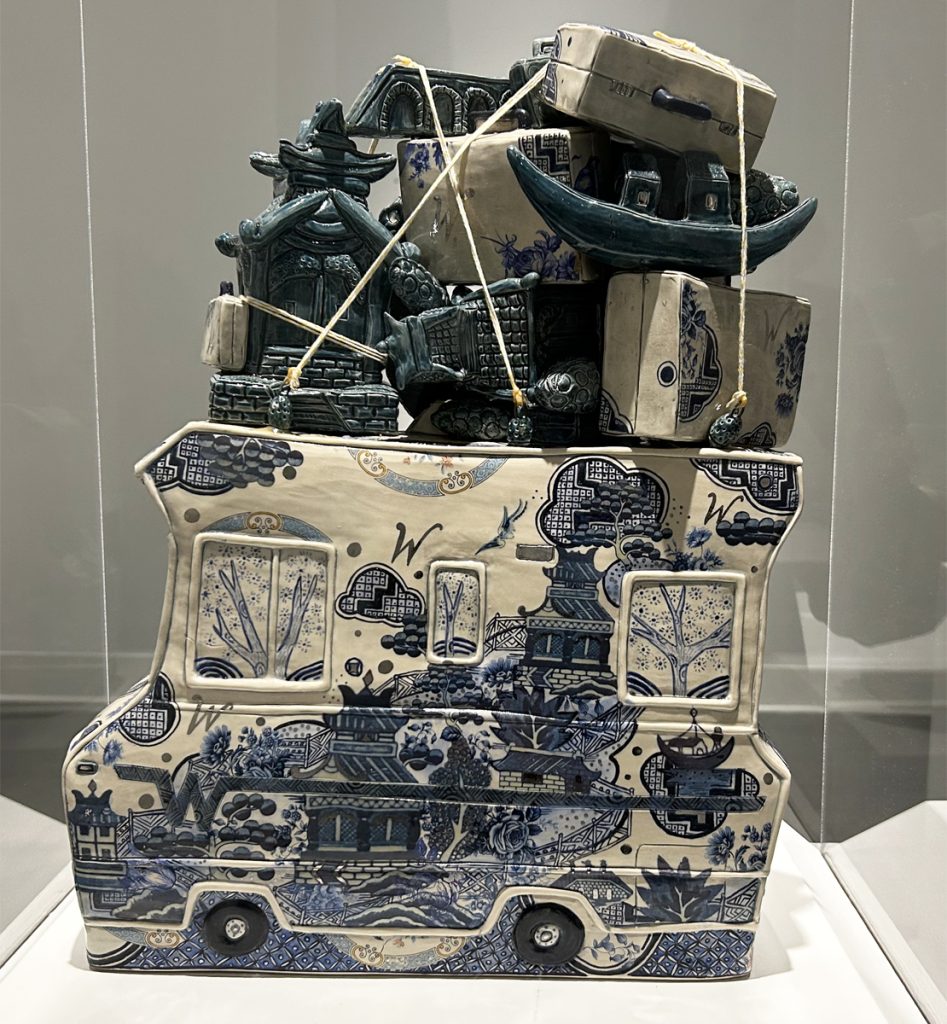

Mariko Paterson, “Willow Bago,” 2014, porcelain/Photo: K.A. Letts

The ostensible premise of the collection is that women artists have been historically limited in their access to the means of designing, manufacturing and making fine ceramics. Before the Industrial Revolution, they were mostly relegated to painting fine china, often in their homes, and only gained broader acceptance as ceramic artists during the early part of the twentieth century. While no doubt true, this turns out to be a bit of a red herring in terms of the actual work in the exhibition. Of the twenty-two artists represented, only two, Clarice Cliff (1899-1972) and Lucie Rie (1902-1995) were involved in what might be termed the mass production of fine ceramics. Clarice Cliff, an English potter, designed and produced fine china under her own stamp in the A.J. Wilkinson factory in Newport, Burslem, U.K. in the 1920s and thirties. She employed a team of seventy china painters (sixty-six of them women) to produce her popular art deco-style designs, and is widely credited as having contributed to a shift in prevailing attitudes toward women in ceramics, from mere decorators to primary creators in clay. Two of her pitchers in the “Fantastique” style are on display in the gallery. To a lesser extent, Lucie Rie worked as a commercial producer of elegant china bowls and vessels that were popularly available in post-World War II British department stores.

Sara Lisch, “Lion’s Journey,” 2002, stoneware/Photo: K.A. Letts

While the artists exhibited in “Making Her Mark” share a gender, they represent a wide variety of technical approaches and formal philosophies. The objects are unique fine art pieces but they vary in their relationship to the historical purpose of ceramics as vessels or their (also traditional) function as raw material for creating sculpture.

In the figurative sculpture camp we find the work of Ruth Duckworth (1919-2009), whose pioneering mid-century abstract objects reference art by Henry Moore and Pablo Picasso, while also showing a formal affinity for archaic Cycladic female forms. Her hand-built porcelain “Black Angel” is a characteristic abstract figure, smoothed, subdued and simplified. Nearby, Sara Lisch’s woman with her pets, “Lion’s Journey,” is a more approachable figure, substantial and serene. Viola Frey’s monumental tower of garishly colored ceramic figures, “A Pile of Figurines and Masked Man,” references the tchotchkes with which we are all familiar. Canadian artist Mariko Paterson’s “Willow Bago,” created in 2014, is a comic send-up of the British Empire, its blue-and-white patterned Winnebago (with the Queen Mother in the driver’s seat) topped by a mountain of bits and pieces—literally baggage—from erstwhile colonies.

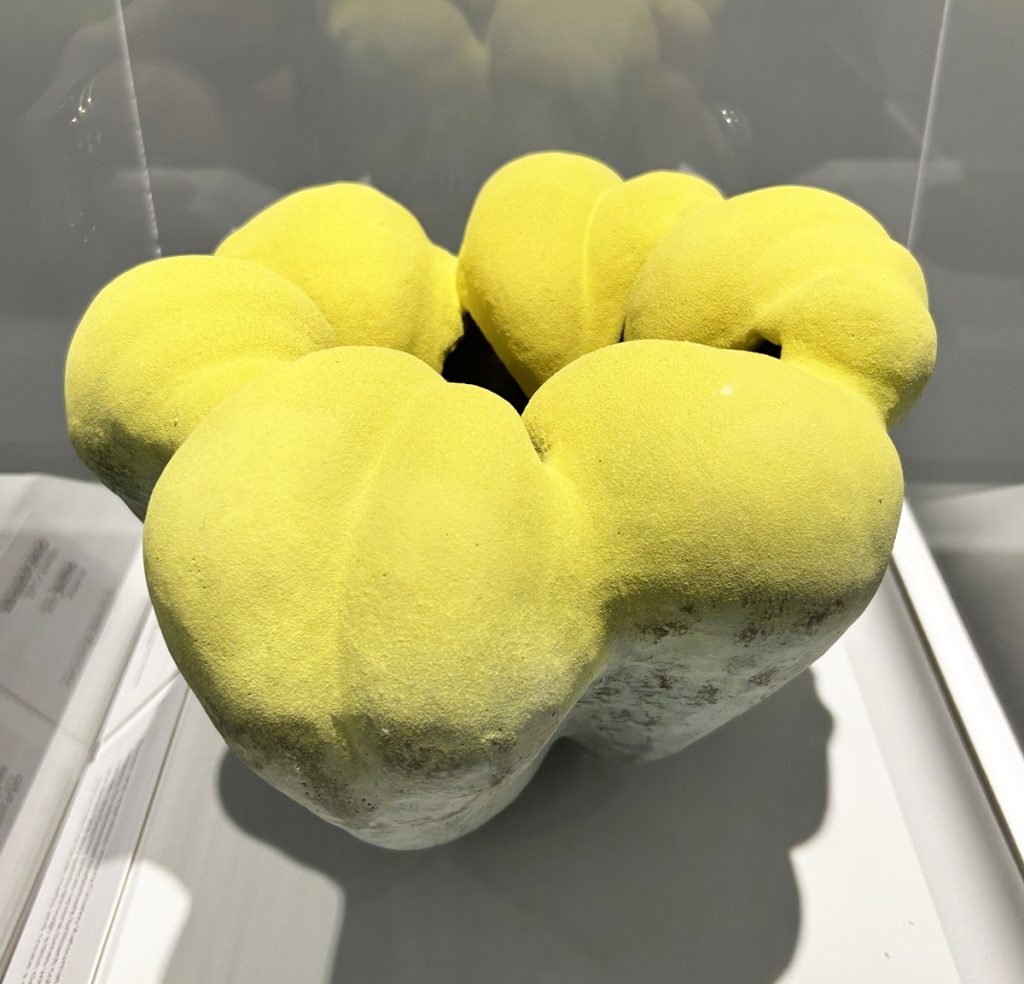

Chieko Katsumata, “Untitled,” 2006, stoneware/Photo: K.A. Letts

The natural world is well represented by a number of the artists who take it as their subject. Seattle artist Carol Gouthro’s “Aurlia Gouthroii Barnaclette” (2012) shows her obsessive observation of nature as source material for fantastical biomorphic sculptures. Debbie Weinstein’s colorful stoneware hybrid container/sculpture similarly evokes the ocean life near her home in South Florida. Chieko Katsumata of Japan draws inspiration from the sea as well—her velvety chartreuse stoneware vessel could easily be mistaken for an occupant of the ocean reef.

The artists whose work most directly references the identity of ceramic objects as vessels focus on the ways in which that identity can be manipulated and altered to expand our understanding of clay’s formal capacities. Anne Marie Laureys’ “Clay-e-motion,” a stoneware vessel begun on the wheel but finished by hand, begins to express the variety inherent in ceramics. The artist discovered that a thin-walled vessel could be folded, stretched and pinched to create a completely new asymmetrical visual aesthetic. The endless sculptural possibilities of stoneware are foregrounded once again with Ursula Morley Price’s delicate “Fountain Plume Form,” which gives the illusion of undulating as the play of light crosses its ruffled surfaces.

Anne Marie Laureys, “Clay E-motion,” 2004, stoneware/Photo: K.A. Letts

At the intersection of vessel versus sculpture, we find the porcelain “Twins” of Russian potter Irina Zaytceva. She manipulates the notoriously finicky material with skill and originality. But the real heart of her work is in the imagery of her painted figures and their interaction with the forms upon which she paints. Using multiple glazes, successively fired, the artist creates a surreal synthesis of image and object.

Though the curatorial emphasis of “Making Her Mark” seems to be on the commonalities of these contemporary artists based on their gender, I observe that they are really distinguished not so much by their similarities as by their differences. Taking the previously mentioned Irina Zaytceva as an example, I found a strong relationship between her work and the surreal ceramics of her fellow countryman Sergei Isupov (several examples of whose artworks occupy a nearby gallery). While Zaytceva’s work is robustly female, it clearly shares with Isupov a fascination with surrealism, stylistic affinity and common technical strategies.

Ruth Duckworth, “Black Angel,” 1999, porcelain/Photo: K.A. Letts

It seems to me that—in addition to gender—ethnicity, national origin and the availability of technical means also strongly influence what gets created and finds an audience. No matter what their historical deficits may have been, clearly contemporary female ceramic artists suffer no current disadvantage in means, methods or access. And the wide variety of work on view in “Making Her Mark” shows them to be fully equal to anyone in technical accomplishment and creative imagination.

“Making Her Mark” is on view at Flint Institute of Arts, 1120 East Kearsley Street, Flint, Michigan, through September 28.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content