Painting a picture of the global art market is not a straightforward task. Not only is the art business made up of a myriad of different players – from auction houses and collectors to industry experts and financial advisers – but it also heavily relies on fluctuating political and social contexts worldwide.

It is no surprise then that the past few years have seen some major shifts in trends and economic value, as the art world has been at the sharp end of political instability and financial crises.

[See also: Putting a price on art: nine factors that drive value]

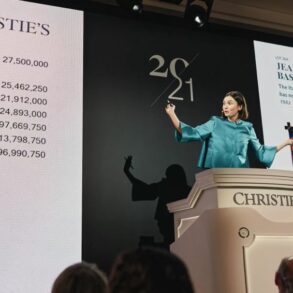

UBS and Art Basel’s annual Global Art Market Report, which was released in March, found that ‘sales were thinner at the top end of the market’ in 2023, given a backdrop of high interest rates, inflation and political instability. The report, which was authored by economist Dr Clare McAndrew, considered the growth of online sales in the art market, and the importance of the Chinese market, which overtook the UK as the second largest centre for art transactions in 2023.

How much is the art market worth?

According to the latest edition of the UBS report, global art sales have slowed by 4 per cent year-on-year in 2023 after two years of post-pandemic growth, reaching an estimated $65 billion (around £51 billion). This number refers to the revenue generated by gallerists, art advisers, auction houses, and all the other art market actors.

[See also: Outstanding art advisers 2024]

Julia Bell, founder of art advisory firm Parapluie and a Spear’s Top Recommended art adviser, believes this decline ‘doesn’t come as a surprise to anyone’.‘It is clear that wider global political and economic volatility and international conflicts have had some impact on the global art market,’ she says.

The current political context has been challenging for both buyers and sellers, she says. ‘Anyone looking to buy or sell will have an eye on the global instability that surrounds us and be cautious of whether the timing is right, in particular [for sellers],’ Bell explains.

However, while the overall value of the art market has decreased over the past two years, the volume of transactions went up 4 per cent compared to 2022 and was particularly high in the lower end of the price spectrum. One of the consequences, Bell says, is the appearance of a ‘buyer’s market’ at the top end of the market. ‘More and more I am being offered works that are for sale privately. Some sellers want their sales managed tightly and discreetly rather than publicly via auction.’

Tanya Baxter, who has been an art adviser for more than 25 years, tells Spear’s that while the art market ‘most definitely needs’ more political stability, ‘art transcends these economic cycles’.

‘Despite market woes, there are always niche markets, particular artists, and masterpieces that defy the trends,’ she says.

Which countries have the biggest global art market share?

The US remains the leader of the global art market, accounting for 42 per cent of sales by value, the Art Basel and UBS report found. While the value is down 3 per cent compared to the previous year, the US still saw a ‘robust recovery’ from the pandemic-induced fall in sales after values went up 44 per cent between 2021-2022.

[See also: The dark art of the deal: the oligarch who lost a billion in the art market]

‘This increase was supported by buoyant demand, particularly at the high end of the market, from local and international HNW collectors, with the US remaining the key centre worldwide for sales of the highest-priced works,’ Dr Andrews wrote in the report.

China (including Hong Kong) and the UK have been vying for the second place position for decades, though China overtook the UK in 2023, with a share of 19 per cent compared to 17 per cent.

This represented a 9 per cent increase for China, with a return to normal auctions and fairs after heavy Covid restrictions, while the UK’s share dropped by 1 per cent.

[See also: UK art market falls behind China amid global dip in sales]

‘The UK’s drop from second place to third place is something to watch,’ Bell says. While she says that Brexit will have had an impact on the way artworks are imported to the UK, and that the drop in top-end sales will have had a knock-on effect on the London market, she explains that the ‘strong growth in new collectors in China’ are helping the fuel the market. ‘[That’s] something we don’t have to their extent,’ she adds.

Bell acknowledges that the current political context in the UK has not helped. ‘What was interesting at the recent Spear’s 500 conference was what appeared to be some indifference to the [July general election],’ she says. ‘As more and more UHNW and HNW consider themselves ‘global citizens’, […] their allegiance to the UK art market should not be taken for granted.’

‘Any new government shouldn’t assume our creative industries can continue to weather these challenges. I have always said we need better tax incentives to stimulate both the buying of art and the charitable donation of works to our public institutions.’

What are the latest art market trends for investors and sellers?

The growth of online sales

While the art market is gradually recovering from the pandemic in terms of value, some trends prompted by worldwide lockdowns have taken root, including the growth in online sales. After a small decline from 2021 to 2022 – partly due to the post-Covid comeback of live sales – global online sales rebounded in 2023, reaching $11.8 billion (around £9.2 billion), or an 18 per cent share of the total turnover.

The flourishing of online sales allowed many HNW and UHNW clients to get used to purchasing artworks without seeing them in real life. However, ‘the tendency for the most expensive works to be predominantly sold offline remained,’ Andrews explains in the report.

[See also: Gallerist Pearl Lam: a champion of Asian contemporary art]

Thomas Reinshagen, who is the former senior director of Sotheby’s Zurich and has over 30 years of experience in the luxury and art markets, tells Spear’s that online sales enable galleries and artists to ‘reach a global audience, breaking down geographical barriers.’ They also increase transparency and accessibility, he says: ‘Price transparency and access to online data and analytics helps buyers make informed decisions, while sellers can tailor their strategies based on buyer behaviour and preferences.’

But the rise of online sales hasn’t just impacted buyers. The growing sales volume due to ‘the ease of entering the online market’ increases ‘competition among galleries, auction houses, and artists’, Reinshagen says. ‘Sellers must differentiate themselves through unique offerings and marketing strategies.’

Attention to diversity in the global art market

In terms of investment, ‘the interest continues to be in “overlooked” artists and art history narratives,’ Bell says. ‘As art history is being revisited and narratives are expanded beyond the white male narratives of the past, we see a much broader, intellectually and visually stimulating field of artists both past and present that have opened up opportunities for both buyers and sellers.’

A greater focus on diversity may have contributed to expanding art markets in non-Western countries. ‘The UK [has been] historically focused on Western art, and may not be fully aligned with these evolving preferences,’ Reinshagen says. ‘The emergence of younger collectors who are more digitally savvy and global in their outlook has shifted attention to regions like Asia and the Middle East, where modern and contemporary art is thriving.’

This shift in values and interests has also been accentuated by the ongoing ‘great wealth transfer’, with millennial UHNWs increasingly taking centre stage in family wealth decisions, including in art market investment. For Bell, ‘the window to sell such collections is timely if sellers want to capitalise on the historical investments they made.’