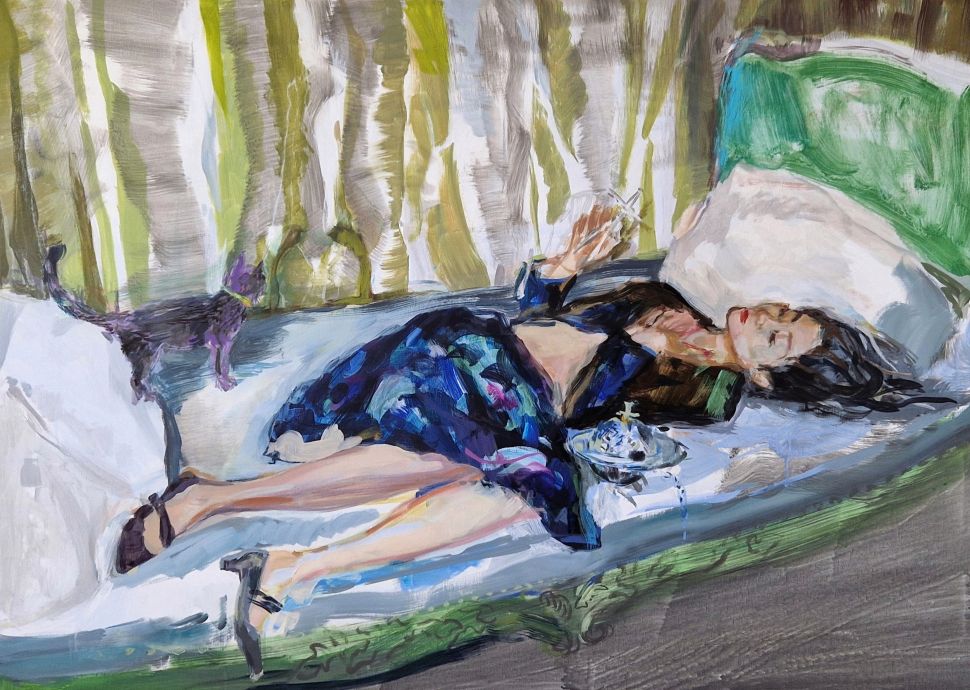

Painted with fluid brushstrokes, a Cantonese woman reclines on a bed of soft blues, strands of her dark hair melting into a plump white pillow. Are her eyes open or closed? It’s hard to tell, as she’s been abstracted into ethereal life by Elaine Woo MacGregor. Unconcerned with the viewer’s gaze, she is instead lost in her own inner world.

The subject is 90s singer Faye Wong, who gained fame during Hong Kong’s pop heyday and has since become a muse to many. Today, this term carries connotations of a passive, female model at the mercy of a great male artist; it has been used unfairly by male critics and artists to downplay women’s contributions, while some feminists have called for it to be canceled.

However, in ancient Greece, the muses were nine divine and powerful goddesses of the arts and sciences. Sisters Clio, Euterpe, Thalia, Melpomene, Terpsichore, Erato, Polymnia, Ourania and Calliope were invoked by poets, musicians, makers and thinkers for creative inspiration and ideas.

For Urania’s Love–Shanghai Flâneuse (2024), Woo MacGregor has drawn on this source imagery, reimagining Wong as Urania, the muse of astrology and astronomy, while inserting modernity into her frame. As she has explained, “Urania is typically seen holding a compass and celestial globe, but these items have been replaced by a Vivienne Westwood handbag and a school drawing compass.”

SEE ALSO: Artist Fawn Rogers On Her Work, Showing at Make Room and the State of the World Today

At the same time, Woo MacGregor riffs on traditions of the reclining female nude, inserting a black cat stolen from Manet’s ‘Olympia’ painting. Yet, her dressed subjects take up space and are in synergy with their surroundings; unposed and unguarded, they please only themselves. Although a public figure, Wong exists privately and on her own terms, relaxing, with nothing to prove. As the artist says, “She is not wearing Urania’s crown of stars; she is a star herself.”

Another star appears in Laughing while Boating (2022), a theatrical painting by Roxana Halls. Depicted as Thalia, the Muse of Comedy, is actress and comedian Katherine Parkinson who cackles, open-mouthed. Seated in a plastic swan boat in the center of a lake, she dangles her legs into the

Through her queer gaze, Halls consciously paints “an alternate world which presents a vision of women roaming, together or alone, in freedom from the constraints of self-consciousness and fear of consequence”. Due to the performative nature of her practice, she collaborates with actors who assume a role in the studio, mining the potential of scenes described by the artist.

As agency is a vital element of Halls’ work, she considers the very language used to describe her subjects: “I much prefer co-conspirator or partners-in-crime to the more passive terms such as sitter or model because I think the terminology we are accustomed to using often casts them in a subordinate, static role which often doesn’t adequately acknowledge their contribution.”

In paintings such as Laughing while Boating, Halls’ protagonists are “emphatically physical, never passive; my women are urgently disruptive and active by necessity”, as she says. Breaking with tradition, she offers viewers the rare sight of women laughing–in the face of societal norms and art history, where they are typically found smiling politely, no teeth on show.

Like Halls, Annis Harrison breaks conventions of tight-lipped women in portraiture, painting unrestrained Black bodies into realms of her imagination. In Words come out to play-ayyy (2024), she portrays Polymnia, the Muse of Sacred Hymns, as not one but multiple women, whose bright red lips stain the bare canvas.

Through this confidently layered image, Harrison has reflected on women’s age-old role as storytellers, saying: “I wanted to evoke Gospel music’s role in informing and educating people who cannot necessarily read, along with Hip Hop which has now finally been ‘recognized’ through literature awards such as the Pulitzer Prize.” Her chorus demands to be heard through the most powerful instrument of all–their collective voice.

A musical score continues in Carolyn Blake’s ambient series, Reframing the Muse (2024), which shares a title with the group show that has brought these artists together at the Oxford Festival of the Arts. For the occasion, Blake collaborated once again with her partner and muse of twenty-six years, Annette.

Across seven small canvases, she appears as Terpsichore, the goddess of dance, who has been brought down from her pedestal. Wearing a striped t-shirt and glowing orange hat, she dances unapologetically in a monochrome space staged with pointed references to mythology: a picture of the three graces, a swathe of deep blue fabric, a Greek vase.

With Airpods in her ears, Annette moves to a soundtrack that only she can hear, as if keeping her memories safe. This is a deliberate choice on the part of the artist, who seeks to frame the “poetic moments of everyday life” while distancing her muse from viewers. As she says, “Annette never faces you, but she does lead you into the composition.”

Meanwhile, behind closed doors, Francesca Currie has riffed on The Rokeby Venus to portray her male actor-friend Lewis as Erato. Depicted with warmth and realism, he looks lovingly upon himself in a mirror that, in the history of art, has typically been associated with female beauty and vanity. Through gender-swapped versions of masterpieces, Currie subverts stereotypes of masculinity while swapping the male gaze for a non-voyeuristic, female one.

Interrogating new ways of seeing, Currie belongs to a vanguard of contemporary women artists who depict a more diverse cast of muses than has traditionally been framed on museum walls. Rejecting romanticized images of the submissive model, while assimilating ancient iconography, they breathe life into goddesses who can be found reclining on their own terms, performing and laughing freely. Reframed, the muse appears as a force of inspiration and an agent of change.