A teenage promoter standing in the rain begs the artist not to drive away before that night’s sold-out concert. It hardly promises a memorable gig, let alone musical history. Nonetheless, after Keith Jarrett reluctantly took the stage at Cologne (Köln) Opera House on January 24, 1975, a recording of his extraordinary performance would become the best-selling solo piano album in history.

The catalogue of mishaps that preceded The Köln Concert has passed into music folklore: how a broken piano was mistakenly brought to the stage and there was no time to change it; how the 29-year-old jazz pianist, befuddled by lack of sleep, back pain, and a 430-mile drive from Lausanne, Switzerland, pronounced the instrument unplayable and refused to perform; how the tearful 18-year-old promoter Vera Brandes pleaded through a car window (“If you don’t play tonight I’m going to be truly f***ed”) while a piano tuner and his son laboured frantically.

Then, when Jarrett relented and took the stage at 11.30pm, kept awake by low-grade pasta, he conjured up a classic. Jarrett’s collage of jazz, baroque, country and gospel, improvised from thin air, has captivated listeners ever since. “The minute he played that first note everybody knew this was magic. That’s something I’ll never forget,” Brandes says today.

Jarrett has released two dozen solo recordings, but it is the concert in Cologne that cements his reputation with the public as a master improviser — or as he prefers to put it, “spontaneous composer”. Over half a century sales of the double album have steadily risen to more than four million.

Like plenty of other jazz greats, Jarrett is a divisive figure: critics say his success gave him too much licence to experiment in public. But many musicians are in awe: another popular improviser, the guitarist Pat Metheny, says: “I honestly can’t think of any musician whose talent equals that of Keith Jarrett.” The 30-year-old Grammy-winning multi-instrumentalist Jacob Collier admires his ability to transcend genres: “He plays with an incredible freedom that is just so inspiring.”

Advertisement

The Köln Concert was a swift success — released in November 1975, it won rave reviews, with Time magazine including it in its list of the year’s best records. Jarrett, who had played with Charles Lloyd and Miles Davis, found a new audience as a pioneer of improvised solo concerts far beyond the jazz clubs. In student digs The Köln Concert rubbed sleeveswith Genesis and Led Zeppelin. Even the long piano solos that John Paul Jones of Zeppelin inserted into live renditions of No Quarter in the mid-Seventies, heard on multiple bootlegs, have a pronounced Jarrett-ian feel.

Events to mark the 50th anniversary this year include the British pianist Dorian Ford improvising round the authorised score at a concert in a Cologne church on January 24 (veterans of the original gig get in free). In April the American choreographer Trajal Harrell brings his Köln Concert dance work to Sadler’s Wells in London. Two films are due for release: a German-made drama, Köln 75, tells the story of Brandes, who had borrowed from her parents to put on the show; Köln Tracks is a documentary by the French director Vincent Duceau, a longtime fan, who sets out to find the infamously wonky baby grand.

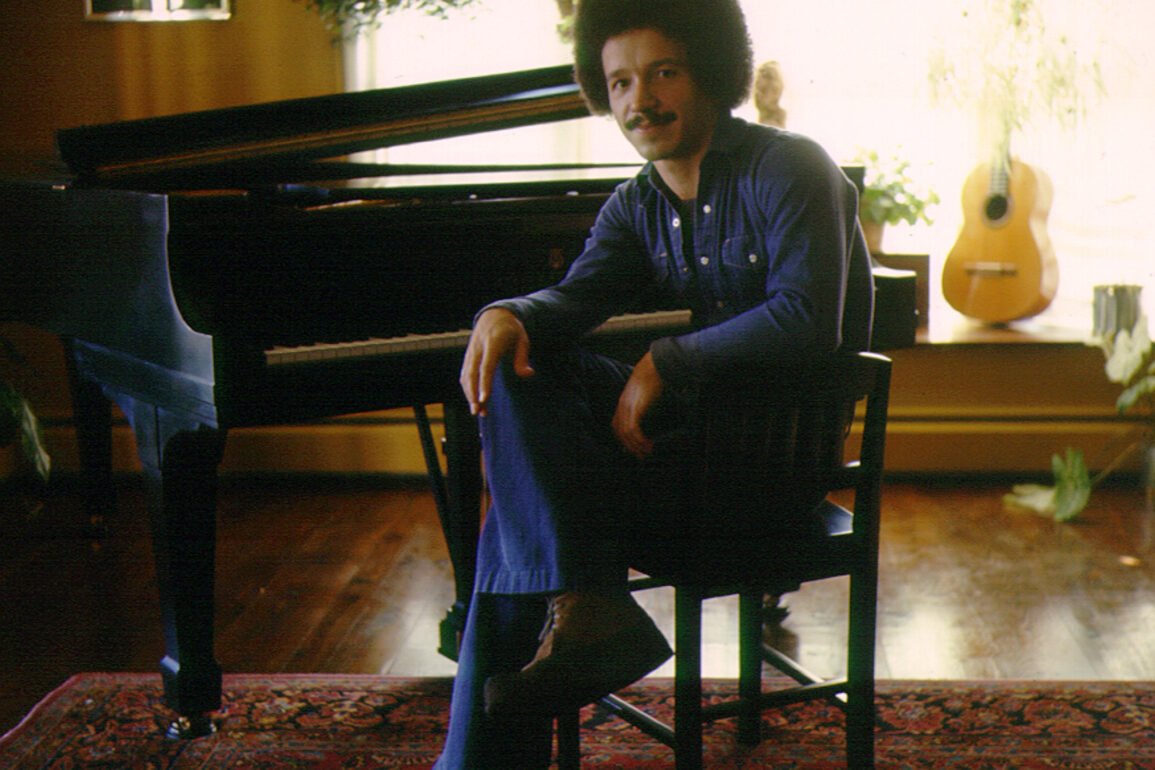

Jarrett in Los Angeles, 1975

MICHAEL OCHS ARCHIVES/GETTY IMAGES

That documentary, though, makes the point that the wretchedness of the instrument grows with every telling. Certainly the Bösendorfer rehearsal piano, which had been mistakenly brought instead of a Bösendorfer Imperial, had tinny high notes and some silent keys. Since it wasn’t a full-size concert grand, the instrument could not generate the volume needed to fill a 1,400-seat hall if played conventionally. But at least it was in tune and Jarrett concentrated on playing the respectable middle register. Rolling left-hand bass riffs made up for the instrument’s lack of volume. The music has a soothing, intimate, almost ambient quality, but also develops with a clear logic. Only the encore (Part IIc) was a pre-composed Jarrett tune.

For all the talk of the calamity of Köln, this wasn’t the only time that Jarrett triumphed over adversity. His back pain meant the rapturous music conjured up in Bremen as part of his Solo Concerts set in 1973 was created on heavy-duty painkillers. His outbursts at coughers would become notorious, but some suspect he used the tension to energise his playing. The piano itself can become the enemy, says one biographer, Wolfgang Sandner, “an instrument that has to be defeated”. Then there was the break-up of his 30-year marriage to Rose Anne in about 2008. As with musicians from Beethoven to Bob Dylan, romantic despair inspired a burst of creativity.

Jarrett’s comment to Melody Maker in 1970 is illuminating: “If everything is perfect, if the piano is in tune, if everyone is sitting quiet and expectant and all the audience are Keith Jarrett fans, then I don’t feel the need to play. It’s the worst possible situation.”

Advertisement

Brandes, who is now an eminent music producer and researcher, always says her pleading persuaded Jarrett on stage. “‘Never forget, just for you,’ he said.” However, Jarrett has told interviewers that he had decided to perform anyway because recording equipment was already in place and the engineer paid; he would keep a cassette for reference. (Later, the missing Bösendorfer Imperial would be located in its usual storage spot by an emergency exit below the stage.)

Jarrett is 79 and after two strokes in 2018 no longer plays concerts. He rarely talks in public, but in the past he has described a “complicated” relationship with Köln. In 2009 he told me: “There are too many extra notes that shouldn’t be there. There is a transcription, but people playing it don’t realise I don’t like it the way it is. If I was ever to record it again from the music — which I won’t — people wouldn’t believe how many notes I’d be eliminating.”

• The 20 best jazz albums of 2024, ranked

Jarrett’s improvising would become more sophisticated over the years, making it less listener friendly at times. On later recordings, passages steeped in modern classical idioms can be densely abstract, atonal, darkly solemn — not the stuff of car stereos. In 1992 he hoped that with his Vienna Concert recording, “maybe, for the first time, I’d have a chance to detox the Köln addicts”. In the sleeve notes he declared: “I have courted the fire for a very long time, and many sparks have flown in the past, but the music on this recording speaks, finally, the language of the flame itself.” And, yes, 24 minutes in, from a firestorm of notes erupts a dazzling 20-minute passage that sounds close to pianistic genius. But this heroic display necessarily forgoes the friendly intimacy that drew listeners to Köln. Closer in style and spirit to Köln are albums from the same era: the 1973 Bremen-Lausanne set or, for those with time and £90 to spare, the six-CD Sun Bear Concerts from 1976.

What also makes The Köln Concert unique in Jarrett’s canon is the sound of audience laughter at the outset (you’ll need to turn up the volume). The pianist had begun by quoting the four-note melody of the signal bell at the opera house that announces the start of a performance. He claims it was unconscious, but even the greatest spontaneous composer has to begin somewhere.

Dorian Ford performs in Köln Concert 50 at Liverpool International Jazz Festival on Feb 23, kolnconcert50.com

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content