Ian Hess is one of those rare souls who’s carved out a place in Richmond’s unpredictable art landscape. As the owner of Supply, a local art store, and a painter whose work is steeped in mythology and meticulous craft, Ian has spent over a decade wrestling with the highs and lows of the creative life while giving back to the city that shaped him.

From his time at Endeavor Studios, where he collaborated with hundreds of artists, to his fight to create a public Art Park, Ian’s story is one of resilience, determination, and a touch of madness. In this conversation, we dig into the evolution of his work—equal parts timeless myth and technical precision—and the unpredictable grind of selling art in Richmond. Ian speaks openly about the realities of the art world, his love for the community, and the bureaucratic battle to bring bold ideas to life.

Listen to our podcast ‘RVA MAG | Ian Hess Interview by R. Anthony Harris’ HERE

Anthony Harris: Today, I’m with Ian Hess. He’s the owner of Supply art store in Richmond, a fine art painter, and he’s also working on—or trying to get done—an arts park within Richmond city limits. Let’s just start with the origin, kind of an overview of how you got started in the arts and how you got to Richmond.

Ian Hess: Yeah, thanks for having me today. Origin story—it’s really the classic tale. I’ve always drawn. I don’t remember a time when I wasn’t drawing. My mom still has these little images from when I was, like, two years old. There’s one where I crumpled up foil to make a Roman soldier’s head and shield, and I used craft paper and gave it anime eyes. She still has it hanging in the laundry room because she doesn’t throw anything away that I make.

It’s just always been there from the beginning, almost like a way to help me focus. I couldn’t think right without it. Teachers in grade school would call me out, like, “Are you even paying attention?” And I’d just repeat back what they’d said, word for word. They’d be like, “Oh, well, make sure you’re taking notes,” or whatever.

But I didn’t know you could actually become an artist. I didn’t think that was a real thing. I thought it was basically like, you’re either Picasso or you’re an asshole. Looking back at history, we’d say, “Oh, those were artists.” But no one ever told me directly that I could be one.

AH: Were you in a small town?

IH: Not really. My parents divorced when I was two, so there was a lot of moving around. We were in Ohio for a while, then New York, and actually Richmond. My mom used to work at The Martin Agency. She worked under Hal Tench when he created the Geico Gecko. She didn’t have creative input on it, but she knew him.

Later, in high school, I had a girlfriend who saw me drawing all the time. She said, “Oh, you must know a bunch of working artists.” And I was like, “Honestly, no, I don’t.” So, she showed me an artist named Greg “Crayola” Simkins. He was always painting monsters, and his origin story was kind of similar to mine because I was always drawing monsters too.

When I saw his work, I thought, “He’s getting paid to do that? He has a family and he travels and paints?” She bought me a hardcover book of his—400-plus pages of his work—and I couldn’t let it go.

When I started looking at art schools, I saw that VCU had a great art program. It was like I had two paths: go into electrical engineering or become an art student. I scraped together a portfolio, spent some time on a few more pieces—probably stole a bunch of ideas from Crayola—and applied. They let me in.

Before that, though, my first real connection to Richmond wasn’t The Martin Agency—it was the hardcore scene. Alley Katz downtown was always doing metal shows, and I thought, “Richmond’s the shit.” It’s still the shit, and it seems to be expanding its prowess, but back then, I thought it was just the coolest place.

I met people at shows—sometimes while committing violence, sometimes while avoiding it. Alley Katz was destructive. It’s probably why I have tinnitus now. But that was the flavor of the city.

When I got accepted to VCU, I thought, “This is it. You’ve got to go.” At the time, I was doing general contracting, working a few other jobs, and going through some rough experiences. But I kept telling myself, no matter how hard the arts get, it will never be as bad as crawling under a house in the summer to put in insulation with a rat scurrying next to you. The arts are difficult, but in a very different way.

IH: Yeah, wow. Yeah, yeah.

AH: You know, of course, finish working, then you need to go back to school and get out of here.

IH: That’s amazing, really.

AH: Short segue there, but—

IH: That’s amazing you met someone who would redirect you like that, in a very blunt, blue-collar way. Like, “What the fuck are you doing, dude?”

AH: One of his eyes was cloudy because he somehow got metal in it from working. He was also the guy we’d get moonshine from. Honestly, I think his eye might have been blacked out from the moonshine, but I told everyone it was metal. Anyway, that guy was a character.

That’s when I thought, “Okay, I need to apply to VCU,” because some of my friends were going there. When I got to Richmond, I actually met Dave Brockie (of GWAR) at an art show. He was in disguise as a squirrel with an American flag. During the show, he did a performance piece where he lifted up his cape and he had a butt, a plastic butt and he shit on the flag. I thought, “This is Richmond. You can do that here.”

So, I started checking out the shows and got caught up in the DIY aspect of Richmond. That’s actually a good segue into my first experience seeing your work—or even knowing your name—which was through Endeavor Gallery. How did that get started over by Gallery5?

IH: Yeah, it was just an impossible set of circumstances. Looking back, my dear friend Eli McMullin—who’s also a phenomenal painter—and I have talked about it so many times. Like, how is it even possible that it went down like this?

At the time, a relationship of mine was ending, and I was about to live totally on my own for the first time—no roommates. I left that situation and was looking for another place to live, but I just couldn’t find a spot. I had applied for a studio, and they very much led me to believe I was going to get it. They told me, “We’ll get back to you in two days.” Two weeks later, I got a message saying, “Actually, we chose someone else.”

So, while I was still searching for a place to live, I hit up a friend of mine from painting and printmaking. His name is Christian. He told me, “Well, not only is my roommate moving out here, but he’s also moving out of his studio.” I was like, “Oh, what studio?”

It turned out to be the same one I had been denied from. That moment, I would say, ended up determining the next six years of my life.

AH: Is that the proper use of the term “kismet”?

IH: Is it? I don’t know. Fortuitous? Yeah, Providence, whatever you want to say. I had felt very faithful, and so I was like, “You need to give me that landlord’s number, like, right now.” I think it was a week later when I actually messaged Eli.

I thought he was, hands down, the most talented painter I had painted alongside, and he’s like, “Oh my God. I never even thought I could have a space.” A lot of the galleries in Richmond—or all the galleries at the time—weren’t showing his work either. Being a graduate of painting and printmaking, it’s like, “Where the hell do you show?”

So, we went into the space. Actually, the person who took my spot in the original studio ended up staying too—her name is Christina Wing Chow. She’s definitely more known for her murals now, especially around town. She’s been traveling, to places like China and back, and all sorts of places.

So yeah, for the next five years, we just doubled down. We sat around in a bunch of chairs, on stools, asking, “What do we call this place? What does the logo look like?” That logo is now tattooed on my wrist.

We hit every single First Friday for four and a half years nonstop. I think we missed two—January tends to suck pretty bad—but otherwise, we did every single one. It was one of those things where we didn’t have any funding. We didn’t necessarily know what we were doing, and the institutions definitely weren’t responsive to us.

But it became this organic thing, a must-go-to spot on First Fridays. Technically, First Fridays ended around nine, but most of our shows went until 1 a.m. People just kept hanging out.

The amount of relationships that started on those nights, the new names that came out of it—some of those people are still together or still making work today. In retrospect, it’s wild. Like, holy shit, that actually went down that way.

When you’re on the grindstone, it’s crazy. You’d literally take everything out of the room, cram it into a tiny wood closet behind the shop, clean up the whole space, hang up all the work, and do First Fridays. There’d be 1,000 people coming through during the night. Then you’d deal with the aftermath—take everything down, pull the studio back out, set it up again, create new work for the next show, and decide on the next show.

That was four and a half years. You’re not sitting there thinking, “Oh, I need to remember these precious moments.” It was drug-fueled insanity playing out in these places. In some sense, it feels like the good old days. In many ways, a lot of this stuff is still going on.

AH: The first time I stumbled across the space and went in, it was interesting. As time goes by, you start to think, “Oh, this is the next generation.” When we started the magazine, it was all of our group doing stuff with no funding, no real idea of what we were doing, just stumbling through, staying up late. But eventually, as you get older, you take on more responsibilities, and you don’t have time for all that stuff.

Seeing you guys, seeing that space, and seeing all these young artists—it felt like the work was represented well. It was strong work. I thought, “Okay, these are the people who will branch off into owning a gallery, or maybe an art store, or murals, or whatever.”

IH: That’s right.

AH: So, maybe that’s a good segue. You’re a fine art painter. When did it start to make sense for you to own an art store?

IH: It was right after Main Art Supply closed. I remember this collective sigh, and at the time, Endeavor Studios was still running. People would come in and say, “I can’t believe they’re closing.” Historically, looking at Richmond, there used to be seven art stores. One of them was this huge, multi-story art store where there’s now a parking deck across from the Fine Arts Building, or a little farther down closer to Lowe’s. It was family-owned and had everything—like a mall of every type of art supply.

I’ve talked to teachers who remember when that store closed, and they were like, “What do we do now?” After that, it was down to two: Plaza and Main Art. Then Main Art closed, and it was like, “Oh crap.” For nine years, I kept hearing people say, “It sucks that we only have one art supply store.”

In the wake of Endeavor Studios closing, it wasn’t—

AH: Plaza is a good art store, but not like a community art store the way Main Art was.

IH: Yeah, that’s fair.

AH: Main Art was family-owned and local. Plaza might be a franchise or something like that. Main Art was where I’d go to get my stuff framed. That’s where I’d shop.

IH: Their frames were gnarly, but, yeah, as you know, there are different types of art stores, and it all depends on who’s running it. You could say there are multiple options if you include places like Michaels. I know plenty of people who get all their art supplies from Lowe’s, or back in the day, Ben Franklin’s. But those places wouldn’t exactly be called art stores. So, yeah, it’s all about the variety.

When Endeavor Studios closed, and I ended up getting the property I’m at now, it was in the wake of 2020–2021. Stuff was rough. We’re on Broad Street, and all these businesses were closing—places I loved. Next door, Blue Bones Vintage and Steady Sounds shut down, and I thought those places were amazing. Then Nick’s Sandwich Shop closed, and that one really hit me.

I used to go there all the time. The Greek guy running it would curse at you while handing over this eight-inch-tall salami sandwich. He’d be like, “I get you a sandwich! Get the fuck outta here!” And I loved it. Then they were gone, and I was like, “Holy crap, this is bad.”

It felt like such a downturn. There was so much destruction in Richmond—though, to be fair, there were positive things happening too. Hard conversations were being had, but small businesses took an absolute boot to the head.

That made me start asking, “What does the Arts District actually need?” And I realized the Arts District had never had an art store. That’s crazy. I’ve done a ton of different jobs, but I’d never done retail. It’s weird—it kind of seemed like a no-brainer to me, but I had no idea what I was doing.

I thought the hardest part would be getting supplies and working with wholesalers. Turns out, that’s one of the easiest parts. The hardest part, by far, has been working with the Richmond city government.

It took me a brutal amount of time just to get a business license. There were so many other things involved too, but that was definitely one of the worst parts. Honestly, it’s a miracle we have as much small business in Richmond as we do. But, yeah, that’s how it all started.

AH: Well, this is an easy conversation because I think that’s a great segue into talking about trying to get this Art Park going and working with the city government on a project. You know, I’ve pitched projects before where most city officials either don’t get it or don’t want to deal with it because it’s a pain. They’ve got their salaries and their goals, and any kind of curveball feels like too much effort. You really have to find someone special within city government to champion you.

You’ve been trying for two years now to get this Art Park off the ground. Where are you at? Can you give us a quick update?

IH: I mean, the start of it came from having immense difficulty getting started doing murals in the city. Even this year, I’ve had, like, five or six projects that were about to happen, and then they just didn’t. There’s a lot of other stuff going on.

But in 2021, I went to Amsterdam with Nils Westergaard. He gave me a place to stay, which he’s still at now. There’s a place there called Flevopark, and they have this amazing graffiti store. They make a lot of the 94 cans and Montana paint there, so the prices are ridiculously low—like, you can get a six-pack of color for under $20.

We’d just bike to the park, and I was like, “So, I can just start painting on this wall, and no one’s going to stop me?” And Nils was like, “Nope.” He started painting his spot, and I started painting mine.

While I was painting, this great artist named Sketch came by and said, “Ah, you’re not quite getting those cuts right.” He gave me some tips, and just like that, I was learning new things. The piece I painted ended up staying for about two months. Essentially, the longer your piece stays up, the higher the honor. There’s a respect to it—you’re only supposed to paint over something if your piece is going to be better.

I did that four or five times, and I just couldn’t stop thinking about it. I kept wondering, “How is this not in Richmond?” It’s the most obvious thing. There’s no complicated infrastructure—no multi-story building or insane logistics. They just used pylons under a bridge, designated it as a park, and let people go wild.

Coming back to Richmond, I thought, “Maybe I could do something like this here.” But where do you even start? Who do you talk to?

When the art store, Supply, first opened, one of Nils’ friends—an artist named Bust Art—ended up painting the wall directly behind the store. Bust is a Swedish artist, very comic book-oriented. It was this weird set of circumstances. The house that wall belonged to was recently bought by this super cool guy named Josh Shaheen. Through a Reddit connection, someone suggested the wall for the mural.

Nils was like, “Isn’t that wall right behind your store?” And I’m thinking, “There’s no way this is happening.” But it did. Fate, kismet—whatever you want to call it. Bust put up the mural, and it was a big celebration.

Bust is an international artist, so he’s out there saying, “Come to Richmond. Richmond’s cool as hell.” The mural got shared like crazy. For the art store, it was perfect timing—a new mural right behind us. Bust even used Molotow Belton, this German paint brand we carry. It couldn’t have started better.

Fast forward a few months, and the City Department of Architectural Review sent Josh a cease-and-desist letter trying to get the mural taken down. Yep, that’s right. So, we decided to fight it.

At the same time, I was already thinking about this park idea, so standing up for the mural felt like part of the same fight. It was about saying, “No, the arts stay in Richmond.”

In fighting for the mural, I got to see how the gears of the city machine operate—and it’s brutal. Richmond city government has a bad reputation, even in other counties and cities. They’re like, “Don’t do things the way Richmond does.” There are amazing people on the inside, sure, but the structure itself is just brutal.

That said, we turned them around. At the meeting on the fifth floor of City Hall, the conversation shifted from, “How do we take this mural down safely?” to, “How do we keep it up for as long as possible?” And the mural still stands today.

The outcry during that time—a huge petition, tons of people speaking up—showed me what they respond to. It seems kind of obvious: when enough people are upset, they take action. But even then, figuring out where to go and which departments to talk to is a mess. Nothing is formalized.

AH: I mean, the city isn’t really built to take in our ideas. That’s what I’ve learned from working on projects involving the city. It’s like, is this economic development? The Neighborhood Association? A little bit of both? And then somehow the mayor needs to get involved. There’s no clear process—no, “Oh, I submit here, then this happens, and then there’s funding available.”

IH: Yep, that’s an important conversation.

AH: You’re going to the mayoral forum tonight, right? ed. note: This conversation was recorded before the November election.

IH: That’s right, for the arts. It’s on Broad Street. I think it could be good. My guess with these things is always the same: it’ll be too short.

They are going to generalize. Who is going to come out and say that they don’t like the arts? It’s like saying you are for cancer. (Laughs) That’s ridiculous! Yes, I am all for that. No! It’s going to be, “Yes, we are for the arts, and we will figure out a way.” Yeah, all you artists will probably be sitting there, staring from the audience, and they are like, “We are going to do something.” What is it? We don’t know. It’s still a concept.

IH: I’ve already reached out to the mayoral candidates about this project.

AH: Is there one—or maybe a couple—that you feel could be good champions for the arts? Or would you rather not say?

IH: I mean, I’ve got no problem saying I’ve had the longest conversations with Andreas Addison and Danny Avula. Andreas gave the project his endorsement, which is significant. He’s been on the planning committee before, so I can see how that can be viewed as important. But at a certain point, endorsements don’t really matter. It’s more about the specific people who need to be involved—like Parks and Rec, DPU, and DPW. Those are going to be the biggest players.

So yeah, it’s good that Andreas gave his endorsement. He’ll probably give it some lip service for now, but it’s not clear how that actually helps logistically. Whoever gets elected, it’ll end up on their desk at some point, as you said—it just has to go through everyone. And that’s one of the biggest challenges of actually pulling this off.

It’s like, where’s the place I can go? Yes or no? Where’s the button? Are we going to press this right now, or are we going to press it “no,” fall into a trap door (laughs), and never be seen again…

AH: (Laughs) …with all the other projects.

IH: Instead, you just get sent into this endless loop where no one wants to take responsibility.

Yes, all the other ones. I also talked to Danny Avula, and his approach was very different. He was pointed in his questioning—not just vague talk about supporting the arts. He was like, “Okay, where is this project at? What’s going on? Who else can I talk to?” It seems like he’s trying to learn more about it. Coming from a pharmaceutical background, I don’t think he’s super familiar with the arts, beyond maybe hanging pieces in hospitals or commissioning a sculpture or something like that.

But he does seem to understand how to make larger movements happen. His questions weren’t about optics—like, “Will this make people like me?” Instead, he wanted to know, “How is this actually going to get done?” And I was like, “This is how I think it will work.” His questions were good—practical, thoughtful.

I haven’t had the chance to talk to everyone yet, but right now, Andreas and Danny seem like the heads. That said, I don’t have a big stake in the political side of this. I’d work with anyone who’s serious about making the park happen. It’s not about me—it’s about Richmond.

Obviously, I’d go to the park in a heartbeat, but this isn’t just for me. It’s a community-based project. At this point, after nearly two years of working on it, I haven’t met anyone who’s outright against it. There are no “no”s. So I’m like, “Okay, where’s the button? What’s the next step?”

Apparently, there’s an official proposal process, and we’ve already done the pre-approval stage, talking to every department. Turns out, Richmond has upwards of 39 separate departments—half of which I didn’t even know existed. And apparently, even the irrelevant ones have to review the proposal. It’s just this amorphous blob of bureaucracy.

There are so many people in Richmond who want to do cool things, but they get turned off by how dysfunctional the system is. It’s literally like, “Where do you go? Who do you talk to?” And the departments—I’ll say this as a major complaint, and the city is aware of it—they just defer to each other.

One department will say, “Oh, you need to talk to them,” and then you go to that department, and they send you right back. I’ve had to get both departments in the same room and say, “Listen, both of you are saying nothing. You can’t eliminate yourselves from making a decision.”

AH: That’s right. Both of them tell you to talk to the other one, and it just goes in circles. Let’s put a pin in this for now. After the mayoral election, we’ll check back on this.

I’d like to end on a high note and talk about your actual artwork, which I think is outstanding.

IH: Thank you.

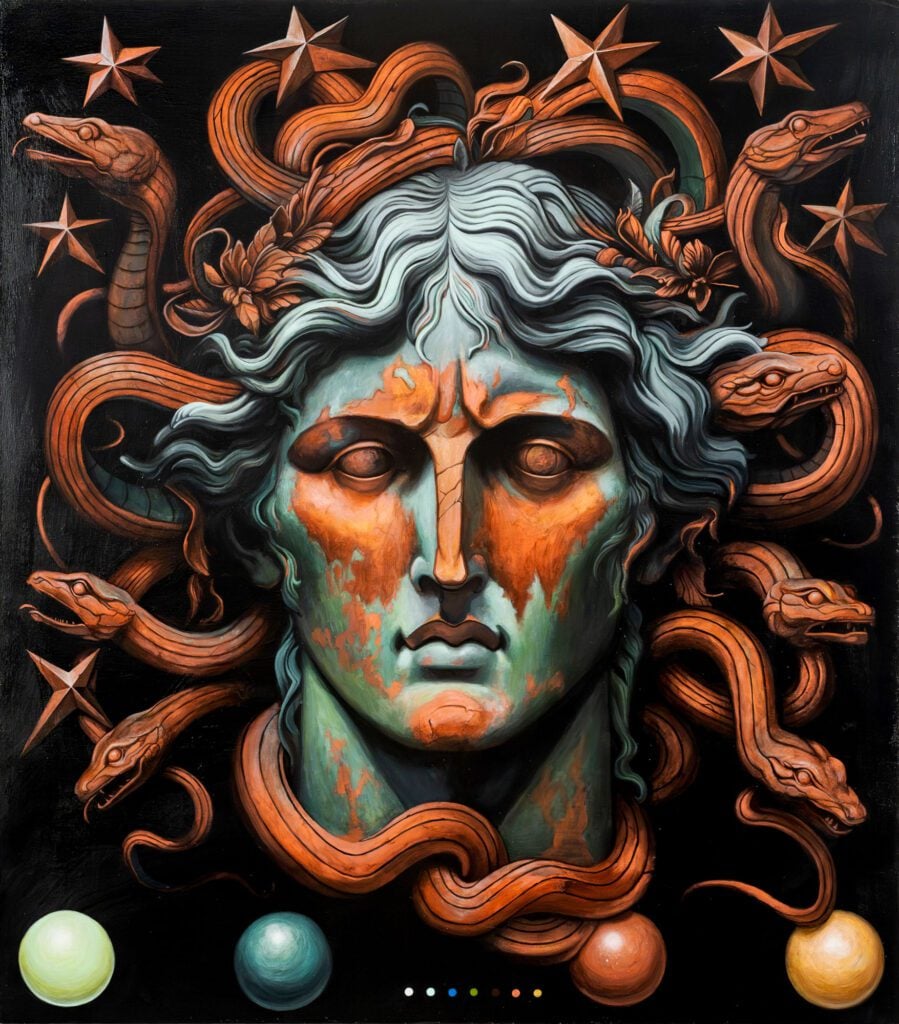

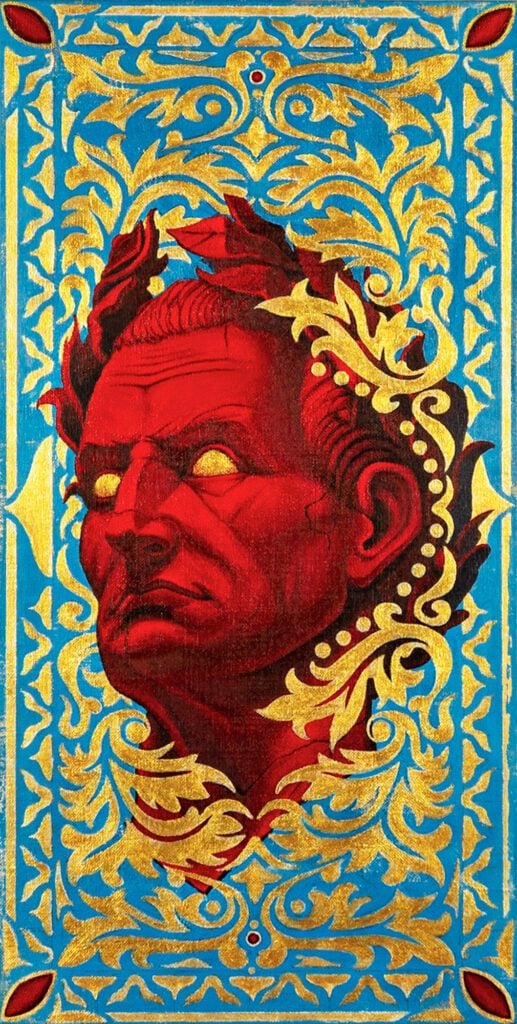

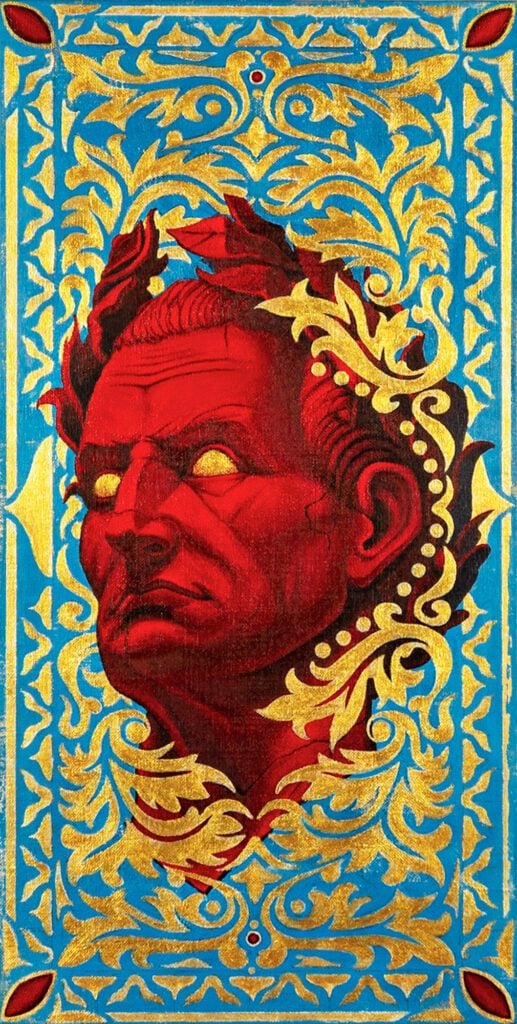

AH: You incorporate a lot of Greek myths in your work. It’s updated and modern in terms of some of the iconography. There’s also this technical precision in how you apply paint—maybe a nod to that engineering path you mentioned you might have taken. What are the overall themes you’re exploring in your work? Ever since I first saw your work and then recently on Instagram, there’s been a clear evolution.

IH: Just as an evolution of the same kind of question, I’m very drawn to mythology in general. I’ve found this really lush landscape in the Greco-Roman myths. In many ways, there’s a lot of crossover between them—different names, same stories—but I think they point to something deeper in ourselves. They reflect these long-standing human conditions, these moments that have defined us throughout history.

A lot of myths come from larger notions. Take the God of War, Ares. He wasn’t just some guy sitting on a cloud. When war was happening, the spirit of Ares was everywhere—ubiquitous. It wasn’t about a single individual; it was this pervasive, deeper force. It’s not a temporary notion or a trend. It’s something that persists, even now. We have different names for it, but that same energy, that same concept, is still here.

I’ve been really fascinated by the way they personified these ideas. Through statues with their highly idealized realism, or even super-realism, and through black-figure Greek vases, which are so flat and stylized, I’ve found a lot of interesting ground to explore. The contrast between these sculptural, dimensional pieces and the almost comically flat vase work is striking. The vases, with their stretched-out figures that feel almost Egyptian, are such a playful space to experiment in.

And they didn’t take themselves too seriously either. I saw one the other day in a museum—a guy giving a thumbs-up to a goose. I was like, “That’s so weird!” And yet, there it is, preserved in a museum. It’s such an interesting mix of the silly and the timeless.

I think what they were aiming for wasn’t just about imagining what the next year or decade would look like. It was about asking, “What does this look like 1,000 years from now?” That mindset is so important. So much of what we make today feels disposable. It’s always, “What’s next? What’s next?” And I get that—it’s essential, especially in something like running news, where you’re constantly focused on what’s next.

But in between the rush for the new, I think there’s this other question: “What stands the test of time?” Why do so many of their buildings still stand? Why is their imagery instantly recognizable, no matter the context?

Even in something as modern as vaporwave—those lo-fi beats with elevator jazz moments—you’ll find Greco-Roman imagery. They’ll use flattened versions or pixelated prints of statues, and no matter how it’s distorted or mixed, it’s still so recognizable. That’s timelessness.

Everything that’s happened since the fall of the Roman Empire or the start of Greece—and yet, their ideals and imagery persist. When I started, I was just trying to line up my work next to theirs, figuring out how to do it now. But I think I’ve gotten a better grasp of it. I can play with it more, push it further. My most recent paintings definitely feel like a level up.

AH: As an observer, I’d agree—you’ve progressed. You’re taking these timeless concepts, like creation and sculpture, and making them your own. I want to shift gears a bit. As a working artist, what was it like breaking into the Richmond art market? How did you approach selling your work, and were you able to get prices that reflected its value?

Ian Hess

Richmond? Yeah, it’s still an ongoing—

AH: …thing, right? Sure.

IH: I think, you know, you’ve got a good baseline of, like, 10 years of doing it. It’s all those questions I think were answered—I didn’t have to answer them outright. It was, like, in the act of doing it, honestly, because of Endeavor Studios. But that’s, like, a rarified thing—not everyone gets that opportunity. And I’m fully aware of that, for sure.

And then, like, the demand—the demand of how much needs to be done to sustain yourself while also growing, fostering a community, and lifting up people—it’s a rising tides sort of mentality. Trying to do all that simultaneously was the month-to-month First Fridays. Like, there was never a show I didn’t also partake in. So, it was like trying to do it alongside people, not ever forcing artists into bad positions or shows they didn’t really want to do. It was very much a collective thing with, you know, hundreds of artists over the years of doing it.

I think, kind of gauging it, you know—I’m in the room. It’s not that big of a room; it’s, like, 1,000 square feet, kind of a right-angle triangle shape. And I’d be standing behind people and hear them talking about my work. Like, “Yo, this fucking sucks. I would never pay for this.” And I’m like, “That’s so… like, ow, first off, but also, that’s so valuable.” Like, this person—maybe they have an engineering background, maybe they’re a nurse, whatever it is—and they’re saying, “I see absolutely no value in this.”

And I’m thinking, “Sorry you said that—damn it. I’ll get you back, dude.” But it was so real because it was all types of people. I didn’t have to look to art markets or online for feedback. It was also a rare time where I didn’t have to give 50% to a gallery. If I sold something, I could meet the person, we’d talk, make a connection. A lot of them became friends.

A great example: the first two pieces I did in this, like, fairy-like Greco-Roman direction. A very dear friend of mine, Anthony Brezz—he does local comedy, music, all sorts of things—was there. I put up these two pieces and declared at the start of the night, or even before the night, “If these two sell, I’ll quit my other jobs tomorrow and start doing this full time.”

So, I was talking to them, and they knew that. And they were like, “Listen, Ian, we think we want to get both of these pieces.” And I was like, “Are you serious? You want to get both of them?” And they were like, “Yes, we do.”

He still has them to this day. I’ve been to his living room—or maybe they’re actually in his bedroom, which, I don’t know, feels like more of a compliment. But yeah, they knew, and they wanted to push me forward for sure. And Anthony—man, he’s been huge. I’d say he’s been more supportive of me than I think I’ve returned to him. It’s a level of giving that I’m like, “Holy crap. How can I ever reciprocate that moment?”

And I definitely think I’ve failed at it. But a lot of times, people will give you gifts, and it isn’t even possible to give them back. Like a good father or a good mother—you’ll never pay that back. It’s like, “This is for you.” And that night felt like that, from them.

It was like an origin story thing—someone giving you something like that makes you want to meet it with hard work, discipline, and whatever else it requires. Because honestly, it’s not possible without that. If it’s not working and you’re not adjusting, you’re screwed in so many ways.

Art, beyond just making something, is the way of doing it. How do you make it your life so you can do this continually? How is it supporting you? Because it’s not just the imagery—whether people like it or not. It’s about what your life is systematically set up for: are you supported, or free enough to grow your craft, get it in front of people, and sell work?

Even for very well-known artists, selling work can be rare. You could have a whole solo show and not sell a single piece. And then it’s like, how is my system set up so I’m not in catastrophic defeat? Like, absolute despair. You know, at the bottom of that government secret door where they pull the rug out from under you.

AH: Highs and lows, right?

IH: Exactly. Somewhere in all of that is the creative process and the desire—the want.

AH: You have to want to do it.

IH: That’s right. You’d better love it, because it’s going to hurt sometimes. When people say, “Fuck you, this sucks, you’re an idiot for making this,” you have to decide if it’s still something you want to do every day.

AH: And see how you respond. Like, “Alright, let’s see what happens next.” Anyway, that’s all I had. I really appreciate your time. Thank you.

IH: Thank you so much.

AH: Hopefully this recorded. Otherwise, I’ll have to write it all from memory.

IH: Fingers crossed. Thank you.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content