On art, gender, Rachel Cusk, and Paula Modersohn-Becker on her birthday.

Paula Modersohn-Becker is following me around.

Well, not literally. She died in 1907 at only 31, two weeks after giving birth to her only child, Mathilde. But the German expressionist painter keeps popping up in my life in ways that feel like too much of a coincidence, making me wonder if she’s here to teach me something.

I first encountered Paula in Rachel Cusk’s new novel, “Parade.” I’ve been devouring Cusk’s oeuvre for more than two years now on the recommendation of my friend Joe, who pitched her to me as “inverted Sally Rooney.” “She is obsessed with personal freedom and the question of whether life is about compromising for others or for living for urself,” he texted me.

I started with Cusk’s “Outline” trilogy and, at first, struggled to embrace her writing style, which eschews traditional plot and character development. Narrator Faye, who is named just once in each novel of the trilogy, is a writer whose experiences—teaching a summer workshop in Greece, renovating her house, going on a book tour—catalyze a series of interactions that serve as a mouthpiece for commentary on gender, class, love, and identity.

Cusk discloses little about Faye. We know she has two children, gets a divorce, meets someone new, and faces a lot of questions about her choice to remarry in a misogynistic world. Usually, she’s listening to other people spill their guts, offering a sympathetic nod or a pointed question, slowly revealing herself through these responses. In the trilogy, character takes a backseat to questioning.

Cusk’s earlier fiction, while more conventional in terms of character and plot, also raises big questions about identity. My favorite, “The Bradshaw Variations,” follows a married couple—Tonie, who gets a promotion at work, and Thomas, who becomes a stay-at-home dad. Bridging the gap between her conventional earlier novels and abstract later ones, the darkly humorous novel asks big questions about art and gender roles that yield often disappointing answers.

There’s a deep thread of heteropessimism throughout Cusk’s work. Take the “Outline” trilogy’s “jarring and ugly” conclusion when Faye, swimming at a beach, finds a moment of solitude disrupted by a naked man urinating in the water. “How free can a woman ever be?” wonders Maggie Doherty in her review of “Kudos” for The Nation. Alongside the author’s nonfiction, which speaks unsparingly about motherhood and her divorce, Cusk’s work begs the question: is womanhood a curse?

It’s worth noting that Cusk’s depiction of womanhood is narrow; her main characters are typically white, heterosexual, cisgender, educated, and middle class or above. (One notable exception I remember is the Bradshaws’ lodger, Olga, a lonely, working-class Polish immigrant with a slew of hardships, who prefers her own magazines to the sad novels Thomas reads.)

Cusk also frequently asks: Is there space for women’s art? In “Bradshaw,” an artist and mother’s complaints that her family demands keep her from working in her studio become a running punchline for her family members—she’s never actually going to make any art. In “Parade,” Cusk doubles down on this question, weaving together seven stories about characters all named “G,” some male, some female, most based on real artists. The female artists are plagued by sacrifice—whether they’re giving up relationships with their family or their true dedication to art.

Last summer, I picked up “Parade” as I prepared to visit my friend Alicia in New York. It was not an easy read—relatively brief, and economical in prose, like most of Cusk’s works, but every sentence was so dense that I felt like it needed to marinate for a while. Each character seemed to narrate an essay; the plot felt so obtuse at times that I wondered why the author bothered making the book a novel at all when it could just as easily have been nonfiction. Above all, Cusk’s treatment of gender felt especially discouraging in its essentialism. Take passages like this:

“His belief is that women are the true creators; they are motivated to give, and in the generosity of their creativity they inadvertently make themselves slaves and henchmen. The creativity of men, which is not creativity at all but a mode of conquest, disgusts him” (Cusk 189).

While I find a lot of truth in Cusk’s sentiments about gender, I often wish I didn’t. I don’t want to feel resigned to a life as a slave or henchman, doomed to a life of sacrifice. I want to want without shame, to have a room of my own. I finished the book feeling weary and pessimistic (it did not help that I probably picked up COVID in New York). In the Cleveland Review of Books, Hannah Kinney-Kobre writes about a similar struggle.

“The experience of reading Parade frequently baffled me, made me want to beat my head against the wall. Her crispness is close to brittleness, her ambivalence so extreme it verges on absolute opacity. And I must admit a certain kind of political anxiety prickled the back of my neck as I read, again and again, phrases like ‘the truth of her female caste’ or “the mystery and tragedy of her own sex.’”

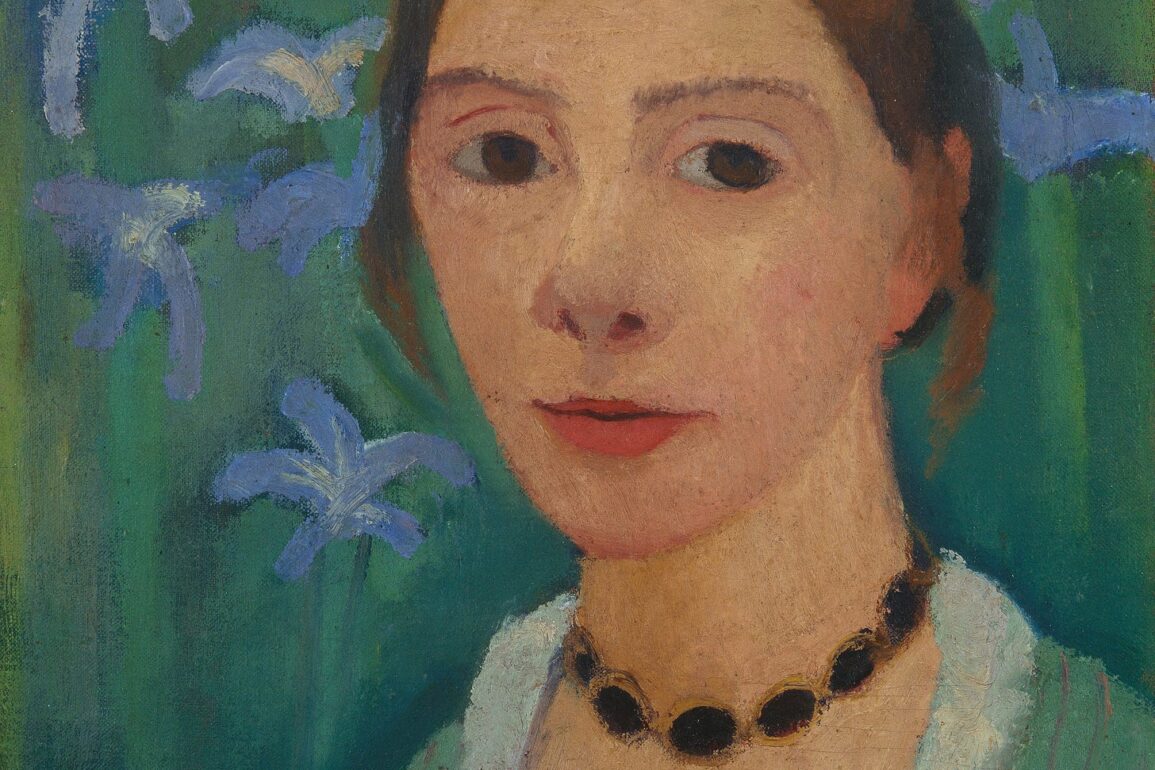

Still, I felt intrigued by the lives of the artists Cusk chronicles. Shortly after starting the novel, I happened to read an article in The Washington Post about a retrospective at the Neue Galerie, a New York museum of Austrian and German art, of a young female artist, who was the first female painter to paint nude self-portraits and who died shortly after childbirth—Paula Modersohn-Becker. “This sounds a lot like one of the Gs in ‘Parade,’” I thought, and sure enough, it was. Alicia and I had to see it.

On my first day in the city, at a used bookstore in Ridgewood, a book about Paula caught my eye: “Being Here is Everything: The Life of Paula Modersohn-Becker,” by Marie Darrieussecq. It felt like a sign, so I bought it.

The next day, we visited the Neue Galerie. We were not allowed to take photos inside, which bummed me out because I love to document the art I enjoy. (Alicia probably was relieved after watching me photograph every single Impressionist painting at The Met on our visit earlier that year.) In a way, though, I felt grateful for the obligation simply to be present, to wander through the intimate and beautiful building as classical music wafted softly through the rooms.

Months later, I picked up “Being Here is Everything.” The book is as much a poem as it is a biography, written by a female writer and mother with a deep personal admiration for the artist.

Born on Feb. 8, 1876, in Dresden-Friedrichstadt, Germany, Paula Becker had a somewhat privileged upbringing. Her mother came from an aristocratic family, and her father was a railway engineer. However, when her uncle attempted to assassinate King Wilhelm of Prussia, her family inevitably faced social stigma. They moved in 1888 to Bremen, where Paula began to learn how to draw.

At her parents’ encouragement, Paula studied for two years to become a teacher, but art had her heart. When she was 20, she took a six-week painters’ course in Berlin; then, she settled in an artist colony in Worpswede, in northern Germany, where she befriended the sculptor Clara Westhoff at painting classes.

“They will be best friends through their studies, their love lives and their misunderstandings,” Darrieussecq writes. “There is no sounder basis for a relationship than misunderstanding” (16). (She’s so right.) Also in Worpswede, Paula met the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, Heinrich Vogeler, and, of course, Otto Modersohn—a married artist she deeply admired.

Paula’s early paintings captured the characters and the liveliness of the small town. “She notices deformities caused by poverty, without reducing them to anything sentimental,” Darrieussecq writes (17). She painted girls and women without the gauze of the male gaze—“women who are not posing in front of a man, who are not seen through the lens of men’s desire, frustration, possessiveness, domination, aggravation” (Darrieussecq 122). I love the way she painted birch trees.

Westhoff traveled to Paris to study under Auguste Rodin, and Paula, after receiving a small inheritance, joined her best friend. There, she discovered the work of Paul Cézanne, which “affected [her] like a thunderstorm,” she wrote to Clara (Darrieussecq 139). I could see how Cézanne’s thick layers of paint and deep contrasts went on to influence Paula’s own work. She also admired the Nabis and Paul Gauguin (ugh, I know) for their bold use of color.

Paula wrote to Otto Modersohn begging him to join her in Paris for the World’s Fair Centennial Exhibition. He hemmed and hawed about leaving his wife, Hélène, who was sick. Ultimately, Otto joined Paula, but not for long—his wife died, and both artists ultimately rushed back to Germany.

Paula’s next few months were full of delights—exploring the town with Clara, enjoying long dinners with fellow artists, and spending Sundays with Rilke, who, despite working in a different medium, seemed to understand Paula and her artistic ambitions like no one else. “Rilke and Paula were both intense in their approach to life,” Darrieussecq writes. “Both knew what they were looking for and what they wanted: to write, paint, find a place where they could be alone to create” (128).

So, when Paula revealed to the poet that she and Otto Modersohn were engaged, it seemed like Rilke took it hard—before long, he pursued Clara, the two were married, and they very quickly had a daughter, Ruth.

Paula felt like her relationship with Clara wasn’t the same after her marriage. She missed her friends and felt upset her letters went unanswered. In reality, life was hard for the newlyweds, who struggled to heat their dilapidated cottage and make ends meet while caring for their daughter. Clara took a job laying bricks; eventually, the couple sent Ruth to live with her grandparents, and ultimately separated, spending a few days together each year with Ruth.

Rilke wrote, “She was unlucky meeting me, because I could not nurture in her either the artist, or that part of her aspiring to fulfill the role of a wife” (Darrieussecq 74). He moved to Paris to write a monograph on Auguste Rodin and work for the sculptor.

It wasn’t easy for Paula, either. She became a stepmother to Otto’s four-year-old daughter, Elsbeth, and hinted in letters and diaries of sexual incompatibility with her husband. While Paula embraced modern art, Otto Modersohn detested it. He denounced Claude Monet and others “who paint[ed] outdoors with their watches in their hands,” preferring art in the German tradition (Darrieussecq 26).

Darrieussecq paints Otto as someone who loved Paula deeply but did not seem to understand her as an artist. This passage from her diary says so much:

“In the first year of my marriage I have cried a great deal and my tears often come like the great tears of childhood… My experience tells me that marriage does not make one happier. It takes away the illusion that had sustained a deep belief in the possibility of a kindred soul. In marriage one feels doubly misunderstood. For one’s whole life up to marriage has been devoted to finding another understanding being. And is it perhaps not better without this illusion, better to be eye to eye with one great and lonely truth? I am writing this in my housekeeping book on Easter Sunday, 1902, sitting in my kitchen, cooking a veal roast” (Darrieussecq 75).

Eventually, Paula returned for a time to Paris, leaving Otto and Elsbeth behind. She was not there long enough. “Only one purpose occupies my thoughts, consciously and unconsciously,” she wrote. She painted prolifically, as Otto grew disgruntled with her “angular, ugly, bizarre, wooden” embrace of Post-Impressionism and reluctance to take his advice (Darrieussecq 89).

Paula decided to spend every winter in Paris. Around her 30th birthday, she left Otto for good, writing in a letter to Rilke the phrase that would ultimately become the name of her first U.S. retrospective: “Ich bin Ich.”

“I’m not Modersohn and I’m not Paula Becker anymore either.

I am

Me,

And I hope to become Me more and more”

(Darrieussecq 105–106).

During this time, Paula produced some of her greatest art, including numerous self-portraits, and sold her very first painting, to Rilke. In a letter to a patron, the poet wrote, “I was profoundly surprised to find Modersohn’s wife in the throes of a deeply personal transformation: she paints—in a very spontaneous and direct way—subjects that, while still in the Worpswede style, could not be perceived or interpreted by anyone other than her” (Darrieussecq 106).

On the back of one of her most puzzling paintings, and perhaps one of her most famous, Paula wrote, “I painted this at the age of thirty, on my sixth wedding anniversary, PB.” In “Self-Portrait at 6th Wedding Anniversary,” Paula is pregnant, wearing nothing but a white cloth around her waist, cradling her round stomach and looking at the viewer with the deep wells that are her eyes.

Interestingly, though, Paula was not pregnant when she made this painting, and not even happily married. Otto sent her love letters and begged her to return, and she rebuffed him. “Dear Otto,” Paula wrote just a month before their anniversary, “How I loved you… But I cannot come to you now. I cannot do it. And I do not want to meet you in any other place. And I do not want any child from you at all; not now” (Darrieussecq 108). Later, in September: “Let me go, Otto. I do not want you as my husband. I do not want it” (130).

But just three days later, her heart shifted. In another letter to Otto, she wrote that she had been upset because he’d blamed her for his “nervous state” in the bedroom, before apologizing profusely. “My wish not to have a child by you was only for the moment, and groundless… I am sorry now for having written it. If you have not completely given up on me, then come here soon, so that we can try to find one another again” (Darrieussecq 131).

Otto returned to Paris, and by March 1907, Paula became pregnant. She wrote Clara, “This past summer I realized that I am not the sort of woman to stand alone in life… The main thing now is peace and quiet for my work, and I have that most of all when I am at Otto Modersohn’s side” (Darrieussecq 134).

Paula’s final self-portraits, painted during her pregnancy, were some of her radical and most striking. Though excited to be a mother, she couldn’t stop thinking about painting, longing to see a Cézanne exhibit in Paris (139–140).

Mathilde Modersohn was born Nov. 2, 1907. After a challenging birth, Paula remained in bed for nearly three weeks before getting up, collapsing, and dying of an embolism, with her daughter in her arms. Her last words were, “What a pity.”

What a pity the artist’s life was cut so short. While Rilke never named Paula in any of his poems, he memorialized her beautifully in “Requiem for a Friend.”

I will buy fruits; and in their sweetness

that country’s earth and sky will live again.

For that is what you understood: ripe fruits.

You set them before the canvas, in white bowls,

and weighed out each one’s fullness with your colors.

Women too, you saw, were fruits; and children, moulded

from inside, into the shapes of their existence.

And at last, you saw yourself as a fruit, you stepped

out of your clothes and brought your naked body

before the mirror, you let yourself inside

down to your gaze; which stayed in front, immense,

and didn’t say, I am that; no: This is.

So free of curiosity your gaze

had become, so unpossessive, of such true

poverty, it no longer desired even

you yourself; it wanted nothing: holy.

In 1927, Paula became the first female artist to have a museum dedicated exclusively to her art. While the Nazis destroyed many of her paintings and marked them as “degenerate art,” Mathilde founded the Paula Modersohn-Becker Foundation in 1978, donating 50 of her mother’s paintings to preserve her legacy.

Given Joe’s assessment of Cusk’s “obsession” with personal freedom, I can see why Paula would captivate the author. She sacrificed her personal freedom for love and family, followed her singular drive to paint at the expense of her relationships, and returned to her partner and family only to die tragically. Paula’s life perfectly fits the narrative of the tortured female artist to which Cusk often clings.

After finishing “Parade,” I wonder: Does writing variations on this theme do anything to move the culture forward? Has Cusk resigned to a bleak view of gender roles, or is she simply telling the truth about being a female artist? Kinney-Kobre says in her review of the novel, “To reveal the particularity of one’s experience is not necessarily to endorse the limitations that have produced it.” But what, exactly, is Cusk doing to challenge those limitations?

Maybe I can answer that question by looking at Paula differently. She was more than a tortured artist, more than a woman victimized by domesticity. She was a woman whose art was her lifeblood, both sure and uncertain what she wanted, living in the “grey reality” Cusk invokes on “Parade”’s final page. She was a human who saw herself and painted herself through her own eyes—and that itself is radical.

Six months after I first saw Paula’s work, I encountered it again, at the Harvard Art Museums, in a simple wooden frame. She painted “Birch Tree in a Landscape” in her early twenties, likely in Worpswede. The tree is luminous; the sun hits it at just the right angle so it pops against a placid background as it reaches toward the sky. I can feel her standing tall.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content