By Lucy Davies,

Private Collection/Annik Wetter Photographie

Private Collection/Annik Wetter PhotographieDanish artist Vilhelm Hammershøi’s paintings had a recurring figure: a mysterious woman with her back turned. Here, through letters and photos, her moving, sadness-tinged story is revealed.

In his 1901 painting Interior in Strandgade, Sunlight on the Floor, the Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershøi depicts a tall window, a lopsided white door and a woman at a table. We can’t quite see her face, or what she is doing, but she isn’t the painting’s protagonist. That role is reserved for the light: the silvery Scandinavian sun that streams through the silent room to cast a pattern on the floor.

SMK Open

SMK OpenIt’s bewitching to see how Hammershøi (1864-1916) took these ordinary things and turned them into modern art. His paintings, which creak with an unforgettable, otherworldly atmosphere, prefigure the work of Edward Hopper and Andrew Wyeth in mid-century America, and the Minimalism movement of the 1960s.

Many paintings feature his home in the old mercantile quarter of Copenhagen. Hammershøi was besotted with its blue-grey walls, old-fashioned wainscoting (panelling), and the way its doors opened on to one light-filled room after another. So masterfully did he capture these that you imagine you can smell the polish that has made his table gleam, or hear the woman’s soft breathing.

Her name was Ida Ilsted, and she was Hammershøi’s wife – they married in 1891, when he was 27 and she 22. She features in about 100 of his paintings, sitting or standing in her lamp black dress, her thoughts elsewhere. More often than not, she has her back turned, dashing any hope of a psychological connection, or clue to her emotional state. Still, the urge to speculate is instinctive and overwhelming.

“The captivating scenes in the paintings of Ida give an initial impression that we are seeing into their intimate world,” says Dr Felix Krämer, a leading expert on the artist, and the curator of Vilhelm Hammershøi. Silence at Hauser & Wirth’s new Basel space, “yet on further inspection few personal details are shown, and for this reason the paintings remain powerfully unknowable and open to multiple readings”.

The exhibition, which is accompanied by a new book, brings together 18 works from private collections and is the first ever solo showing of the artist’s paintings in Switzerland. That might seem surprising given Hammershøi is now the most sought-after Danish artist of all time – his 1907 painting The Music Room, Strandgade 30 sold for $9.1 million last year. But for most of the 20th Century his work languished in obscurity, the modest reputation he had established in his lifetime (admirers included the poet Rainer Maria Rilke and the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev) not revived until the 1990s. The 2008 retrospective at the Royal Academy, London was his first in Britain, and even today there are only three of his works in UK collections.

Frederik Riise/Royal Danish Library

Frederik Riise/Royal Danish LibraryMuch comes down to the fact that the paintings do not slot easily into any of the “isms” and innovations that form the dominant narrative of Modernism. Indeed, though he was born the same year as Toulouse Lautrec and a year after Edvard Munch, Hammershøi always ploughed his own quiet furrow.

Though he and Ida might have travelled to all the artistic centres of Europe – Munich, Berlin, Paris, London and Rome – they shunned cafe society and the parties that lubricated that glitzy world. In Copenhagen, they lived as near recluses, turning their ancient apartment into a kind of laboratory for Hammershøi to study light’s dialogue with architecture to his heart’s content. He painted its interior 66 times in 10 years.

The lone woman in art

The motif of the lone woman in an interior probably came from Vermeer – whose paintings were rediscovered in the 19th Century and were very much in vogue – or from the Rückenfigur (“figure viewed from the back”) of German Romantic painting – Caspar David Friedrich’s Woman at the Window (1822) is a fine example. It shows his wife, Caroline, gazing at boats on the River Elbe, though it’s the spring sky outside, and the hope and spiritual yearning it represents, that Friedrich wants us to focus on, and it draws the eye like nothing else.

Other artists of this era painted lone women beside windows but directed the viewer’s gaze inward, to create a sort of pastoral of domesticity. In these tranquil rooms, the windows brim with light, but the view outside is faint. These types of paintings were the speciality of Hammershøi’s friend, Carl Holsøe.

Paintings of interiors, too, were in the ether. In 1876, the French novelist and critic Edmond Duranty had written a controversial 38-page pamphlet placing domestic scenes at the heart of “la nouvelle peinture”. In order for art to have any relevance, he said, it must concern modern life as it unfolded, in private rooms, on the streets. He pointed to the new style of realism in literature (Zola, Balzac) as an example, though his pamphlet was really a response to the Second Impressionist Exhibition, at which Degas, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, Caillebotte and Morisot had all shown paintings depicting interiors.

Hammershøi would have seen the fallout from this debate when he visited Paris in 1891, immediately following his marriage. The couple had become engaged the previous year, in Ida’s hometown of Stubbekobing. She was the daughter of a wealthy merchant and the sister of Hammershøi’s former classmate at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Peter Ilsted.

It’s thought that Hammershøi asked Ida to marry him at least partly to help her escape the family home. “Ida’s mother is once again as mad – to put it bluntly – as she can be,” Hammershøi writes to his mother in June 1891. “There take place the most frightful scenes, which I won’t even attempt to describe.”

Certainly the speed at which the engagement happened surprised Hammershøi’s younger brother, Svend, who wrote: “Dear Vilhelm! Congratulations, I am looking forward to making the acquaintance of your fiancée. It was a great surprise, at any rate for me. I never would have thought you would ever consider becoming engaged.”

SMK Open

SMK OpenAuthor Jesper Wung Sung, whose novel Kvinde set fra ryggen, (Woman Seen from the Back), imagines a fictional life for Ida beyond Hammershøi’s paintings, tells the BBC that he discovered files in Denmark’s Royal Library which stated that Ida’s mother “was diagnosed with ‘hysteria’. The doctors in the mental hospital noted that she was ‘clever’ but ‘bad-tempered’, and that she had several times discharged herself against the hospital’s recommendation. At the bottom of her file it is noted: “Has seven years ago lost a son due to diphtheria”. This is Ida’s brother Hans Christian. Which means that her mother’s illness probably – at least partly – was caused by unresolved grief.”

To commemorate the engagement, Hammershøi painted a beautiful portrait of his blushing fiancé. It pleased him greatly and he showed it to the visionary art dealer Paul Durand Ruel in Paris, who snapped it up for exhibition in his gallery. Apparently Renoir was among the many artists who admired it there.

What we know of their relationship

Paris was the first of many trips the Hammershøis took together. “Vilhelm and Ida form a rare and beautiful unity,” says Wung Sung. “Unlike many other artists, Vilhelm never leaves her, never travels alone… Ida is with him everywhere – it is unheard of for a couple to be together 24/7 at that time.”

In 1902, the Danish poet Johannes Jorgensen recalled – in an article he wrote for the Danish newspaper Vort Land – seeing the Hammershøis on the via del Corso in Rome. “They looked so nice and homey and a little lost, the two Danes, as they stood there reading the sign on a street corner… her soulful, intelligent, slightly stylised head, her simple blue cotton dress glared so conspicuously against the sheen and rustle of all the silk.”

On these trips, Ida always wrote dutifully to Hammershøi’s mother, Frederikke. In November 1890, for instance: “You mustn’t be afraid, dear mother-in-law, that Vilhelm’s paintings will become infected by the French, for here there is much to learn but not to imitate.”

Royal Danish Library

Royal Danish LibraryFrederikke was a formidable woman, who had idolised her son from birth, and kept a scrapbook of his achievements. He was still living with her when he became engaged. “[Ida] had to live with the constant awareness of being in her mother-in-law’s loving but vigilant gaze,” writes the artist’s biographer, Poul Vad. “She was touchingly naive, and good. She ardently wanted to live up to the role of loving wife and her (adored) husband’s support.”

Of course, we can only speculate as to the nature of the Hammershøis’ relationship. “We get brief glimpses of Ida through some of the letters,” says Krämer, “but few concrete details about their interactions are known.”

Certainly the great number of paintings in which Ida features suggests a solidarity, even devotion. “Hammershøi chose to paint her many times, and they would have spent a significant amount of time together,” says Krämer.

It’s tempting to think that they might have discussed a painting’s composition. There is no evidence for this, though her letters suggest that she at least understood how he worked. In 1912, she writes: “we have rented two capital rooms [in London], from which Vilhelm also thinks he is able to paint. He does always need a little time to look about and be fond of it before he begins.”

She also bought for Hammershøi a photographic reproduction of a painting he particularly liked – Perugino’s Apollo and Marsyas, ascribed to Raphael at the time – for Christmas. His 1895 painting The Music Room shows that he hung it where he might appreciate it daily.

The difficulties Ida faced

Still, life as Hammershøi’s wife would not have been easy. Even his closest friends described him as shy or eccentric and Frederikke was surprised enough at his taking a day away from his easel for his birthday in 1906 to write about it in a letter to his brother, Svend.

“I don’t paint quickly, I am rather long about it,” Hammershøi himself said, in a 1907 interview. And no wonder: when Interior in Strandgade, Sunlight on the Floor was cleaned for an exhibition in 2012, the conservator identified upwards of 40 different whites.

SMK Open

SMK OpenHammershøi’s dedication to his work might explain why the couple did not have children; that or concern that the malady that afflicted Ida’s mother was inheritable: in May 1895, Frederikke writes to Hammershøi’s sister Anna: “Vilhelm has been so kind as to offer me space with them; but I do not think I shall accept as I would be in constant fear of Ida having one of her attacks”.

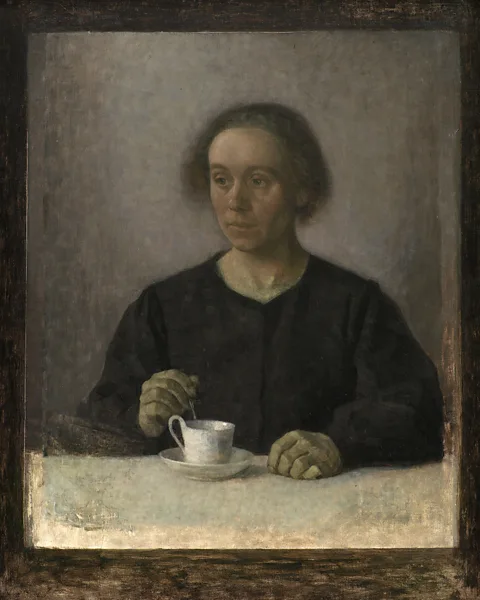

Hammershøi painted Ida for the last time in 1907. The previous 12 months had been trying: the couple had been mistakenly arrested in Rome when some banknotes they had bought in Copenhagen were found to be counterfeit. The misunderstanding was reported in Danish newspapers, who said that Ida, still delicate from a serious operation the previous year, was suffering from nervous shock.

The painting, says Wung Sung, “is a portrait of a woman who hasn’t lived an easy life, but at the same time it’s a very tender portrait. It’s Vilhem’s way of saying: This is the woman I share my life with.”

More like this:

Hammershøi kept the painting with him until he died, after which Ida vanishes from the record, until her death in 1949. “It almost breaks my heart to know that [she] did not live to see Vilhelm’s work become popular,” says Wung Sung. He tells me that her death is listed as “suicide”, though further research led him to believe that it was “not a normal suicide”, and more likely that an elderly, tired Ida chose to refuse treatment for an illness.

An enigma to the end, then. Neither the threads of her biography, nor the more than a hundred incarnations of Ida in Hammershøi’s paintings lead us to any more than a clutch of guesses and assumptions. Ida’s mind and Ida’s world are beyond our reach, though the power of the paintings is that we persist in trying.

Vilhelm Hammershøi. Silence is at Hauser & Wirth, Basel until 13 July 2024. An accompanying book by Hauser & Wirth Publishers, features essays from the curator Felix Krämer and art historian and author Florian Illies.