The gala drew 1400 impeccably attired members of the east coast’s social, cultural and political establishment, including new premier Jacinta Allan, Hunger Games heartthrob Liam Hemsworth, and Melbourne Opera board director Anastasia Kogan, the wife of retailer and Rich Lister Ruslan Kogan. She cut a swathe through the glittering throng in the Galaxy dress she commissioned for the night from Melbourne-based textile artist Troy Emery – a gown-cum-artwork with an enormous skirt swirling in giant circles of acid-bright colour.

This feature appears in the Arts issue of AFR Magazine out on February 2. Louie Douvis

The majority of attendees enjoyed a lively cocktail party, which filled the ground floor of the gallery from 8pm to 1am with ballgowns and brocade-embellished dinner jackets. Moët & Chandon waitstaff worked double time pouring champagne into silver goblets alongside a looming tower of champagne glasses, endless platters of perfectly presented canapes and a closing DJ set by Sneaky Sound System.

Two hours earlier, 400-odd VIPs were ushered into the inner sanctum; a sit-down dinner in a car park transformed into a catacomb-like space lit up by thousands of candles, chandeliers and columns clad in luminescent white panelling. Eventually, the two parties converged in the Great Hall, in what Ellwood says is his favourite moment of the evening.

The event doesn’t raise a single cent on the night and Ellwood, who for this year’s bash donned a new Issey Miyake blazer picked up in Tokyo, is adamant it’s not meant to. “This event is not a fundraising event. This is a break-even event. Its agenda is about thanking and about profile, and building that,” he tells The Australian Financial Review Magazine.

But while there’s no immediate “ask” – beyond the cost of the ticket, which ranges from $400 to $2000 – the evening is a linchpin in the gallery’s money-spinning efforts. The 500 individual donors who have attended every one of the gallery’s gala events over the past five years are collectively responsible for more than $150 million in donations towards acquisitions in that same period. And then there’s the exposure. Some 30 million social media posts, shares and impressions were generated within a week of the event. Ellwood says this figure will grow as the snaps of couture-clad stars continue their orbit around the world’s smartphones.

“It profiles what the gallery does to the philanthropic community, but it also spells out to the broader community the dynamism of what’s happening inside the gallery,” he says. “It’s also become a great way to attract international attention at a time when international philanthropy for us is on the rise.”

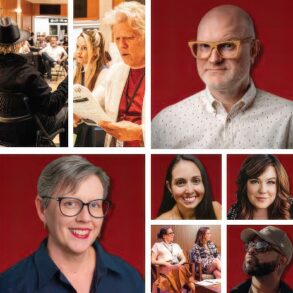

NGV Gala: In the front row are Melissa Leong; Yorick Piper and Jacinta Allan; Lindsay and Paula Fox. In the top row are Peter Wetenhall and Jo Horgan; Tom Mosby and Tony Ellwood; Krystyna Campbell-Pretty; Liam Hemsworth and Gabriella Brooks.

And then there’s the government piece. “It’s a very good room,” is how one senior Victorian politico described this year’s dinner. Attendees included trucking magnates Lindsay and Paula Fox, who in 2022 gave $100 million in aid of a new building dedicated to contemporary art. Seated nearby was Allan in a chic black gown with ornate diamante detailing, fashion philanthropist Krystyna Campbell-Pretty resplendent in gold, and Rich Lister Mecca boss Jo Horgan, tasteful in geometric Dries Van Noten. All 400 tickets priced at $2000 sold out within 24 hours. The wait list alone could have sold out the event again.

Veteran fundraiser Skye Leckie, the society queen recognised for turbocharging the Gold Dinner, is adamant that every evening of froth and bubble has to be underpinned by a defined message. “These are never just get-togethers,” she says. “No matter what, it’s got to be an informative evening as well. You can’t ever lose sight of the message that people are taking out of the room … you need to treat it like a walking press release.”

Ellwood is in fierce agreement, and is blunt in describing the gala as the physical, experiential manifestation of everything the NGV stands for and wants to be. “We look at every single detail, and we treat it as a major event that is representing the highest end of our brand. So we don’t want to put a foot wrong . . . People can tell when it’s quality and when they are cared for.”

In a light-filled office overlooking the ferry wakes of Circular Quay and the sails of the Opera House, MCA director Suzanne Cotter is talking about her plan to plot a course through the choppy waters of the museum’s uncertain funding outlook. Chatty and affable, Cotter joined the MCA in 2021 after spending more than two decades in leading roles across London’s Serpentine Galleries, New York’s Guggenheim Museum and Portugal’s Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art.

MCA Artists Ball: In the top row are Monica Tu; Hai Lan and Yolanda Wang; Luke Sales and Anna Plunkett. Front row: Bridget Pirrie and Stephen Grant; Lorraine Tarabay; Suzanne Cotter; John Symond and Amber McDonald; James and Hayley Baillie.

When asked if the MCA’s money dramas are turning her stomach into knots, she recalls a recent corporate development exercise inside the museum, which included emotional intelligence metrics. “Let’s put it this way. Someone said, ‘for most people, their stress levels are sitting around their hips. Yours seem to be up around your ears’,” Cotter says, laughing. “But how I see it, is that this is an opportunity for us. I don’t know if it’s a crisis . . . It’s a really interesting and appropriate time for us to re-examine everything and say, ‘right … maybe our model is not right?’ Or ‘how exciting to imagine a different kind of model.’”

Unlike the Art Gallery of NSW, the Opera House and the Powerhouse, the MCA is not a NSW state cultural institution. That means it gets very little government money – the $4.2 million it received in fiscal 2023 equates to just 15 per cent of its funding and is equivalent to $2.82 per visitor. As for the NGV, it received $80 million in government grants in 2022 – almost half of its total revenues of $166 million. This equates to about $33 in government funding for every visitor.

While the MCA doesn’t get much taxpayer funding, the NSW government does provide its Circular Quay building free, parts of which the MCA sublets to generate more revenue. It has always relied more than most on philanthropy, and the philanthropy is getting more competitive, especially since the AGNSW sucked up $100 million to pay for its new wing for contemporary art. Last year, the MCA drew slightly under 1.7 million visitors to exhibitions onsite and offsite, including 62,000 students through the gallery’s education programs.

By comparison the NGV drew 2.4 million visitors through its doors over the year, including about 90,000 students who participated in the gallery’s education programs. MCA insiders argue it outperforms on community engagement and outreach for its size, while also noting that community benefits are much harder to quantify than admission numbers.

Anastasia Kogan in the dress she commissioned for the night from Melbourne-based textile artist Troy Emery. Getty

Cotter arrived at the museum in the depths of COVID lockdowns and in the wake of a 20-year stint by her tartan-wearing predecessor Elizabeth Ann Macgregor. Her mandate from the board and the museum’s staunchest supporters was to turn over a new page – “they said to me, ‘refresh, refresh, please refresh!’”

But the task was complicated by the locked doors and social distancing, throwing up a raft of literal barriers between Cotter and the city’s stakeholders. Some think the museum’s relationship with government decision-makers – since replaced by the Minns government and Arts Minister John Graham – needs work.

Cotter has form in working well alongside governments. During her most recent post in Luxembourg heading the Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, known more widely as Mudam, she was “on speed dial” for the country’s Ministry of Culture, which used the gallery as its first port of call to showcase the European capital. State funding covered 80 per cent of the museum’s costs.

An earlier stint from 2012 to 2019 as the director of Serralves Museum, which is Portugal’s top contemporary art collection, was even more instructive. She grew so close to the government that her staff were tapped to decorate the prime minister’s public residence with the museum’s collection.

Tony Ellwood: “This is a break-even event. Its agenda is about thanking and about profile.” Nicole Reed

“We were not considered to be a state museum, but because of the benefit, the economic benefit, and what we projected in terms of Portuguese culture – showcasing Portuguese art and the best of international art, design, building and incredible cultural heritage … everything about that was recognised,” she says. “The prime minister would come to our openings because our work and art was taken very seriously.”

It’s an approach that has worked at the NGV. Insiders in Melbourne philanthropic circles point out there was a lockstep relationship between the gallery and the Daniel Andrews government, which looks set to continue under Jacinta Allan. (The former premier attended December’s gala too, with wife Catherine in pearls and a pouffy red and black ballgown). The Victorian government has committed to helping the gallery realise a $1.7 billion revitalisation of the precinct around the Southbank institution, including the new contemporary art wing, even if it is yet to detail how much funding it will hand over.

Those inside the government are frank about the reason for the support, noting the gallery’s “off the charts” benefit-cost ratio – government-speak for return on investment – which is among the most attractive in the public sector and on par with major international events including the Australian Open and the Melbourne Grand Prix.

At the same time, Melbourne powerbrokers point to the effectiveness of Janet Whiting as president of the NGV Council of Trustees. The prominent lawyer also chairs Visit Victoria. Little wonder the gallery has timed its exhibitions to be in step with the city’s tourism aims, such as the Melbourne Winter Masterpieces series – under which the NGV has brought Degas, Van Gogh, Monet and Picasso to attract tourists in the off season.

Suzanne Cotter (left) and Lorraine Tarabay at the MCA in Sydney.

Louise Kennerley

“They just know how to play to the city’s strengths, and it’s a huge boon for interstate tourism and international tourism,” one politico says. “They’ve got this ability to attract those really compelling exhibitions – not just an artistic success, but also a commercial success – and to hit those two marks is very important. It’s just an easy sell.”

For Tarabay and Cotter, the new-look MCA Artists Ball ran exactly as intended. The event, a top-to-toe refresh of the museum’s long-standing annual benefit, the Bella Ball, was a clarion call that the MCA was making a comeback after a quiet few years of leadership change. It was also about survival. The directors knew there was more urgency than ever to get the sell right, and they insist it hit the mark – winning new corporate sponsors and a new legion of supporters who will soon convert to donors.

“No one lost sight of the fact that there were two goals . . . it’s as much about communicating a vision as it is about raising money. They are two completely interconnected aims,” Cotter tells AFR Magazine. Tarabay is even more blunt. “It’s also about image and branding,” the former investment banker says. “And for us, it’s becoming even more important with all the competition to differentiate ourselves.”

The second iteration of the Artists Ball is already in planning. Cotter and the team are mulling another Australian artist to honour and an evening of experiences that will jolt the most champagne-wearied benefactor from the canape carousel. They have good reason to think big. A few kilometres away is another major art institution with a giant new wing and cavernous spaces that led Paul Keating to once quip it’s a “special events complex masquerading as an art gallery”. It’s the perfect spot for a party.

The February issue of AFR Magazine – the Arts issue – is out on Friday, February 2 inside The Australian Financial Review. Follow AFR Mag on Instagram.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content