Setting

The HS3 and EHSEC projects have provided support for HIV services in five of the 31 provinces in the Dominican Republic: La Romana, National District, Monte Plata, San Pedro Macoris, and Santo Domingo. There are 72 ART clinics in the country, 15 of which were supported by HS3. Through the project, teams of trained clinical providers and peer outreach workers who spoke Spanish and Haitian Creole offered navigation and HIV clinical services in alignment with national policy and guidelines, including HIV testing, prevention services including pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and treatment services at community sites and government and civil society organization (CSO)-led health facilities. HS3 and EHSEC provided subgrants to CSOs to offer HIV testing in the community or at their own facilities, ART services, as well as to navigate clients to the public facilities for testing and ART, as needed, according to client preference. Community clinical sites were located at hot spots—defined as areas of high HIV vulnerability, including streets, bars, clubs, brothels, markets, and squares where individuals engage in HIV high-risk behaviors. Hot spots were identified through a standardized mapping activity conducted through the support of key informants and peer networks. The geographic coordinates and characteristics of hot spots (i.e., typology, estimated number of clients supported by the project, key days and hours when project clients gathered, nearby services of interest) were documented in encrypted files. Community HTS was typically offered in community spaces temporarily rented by the project and at client residences.

Aim and design

The aim of our analysis was to learn the case-finding rates achieved through standalone index testing and the integrated index-EPOA approach among Haitian migrants and individuals of Haitian descent in the Dominican Republic served through the HS3 and EHSEC projects.

We analyzed retrospective client records using routinely collected, aggregated program data for clients meeting the inclusion criteria in four of the five project-supported provinces: La Romana, Monte Plata, National District, and Santo Domingo. Although the projects’ geographic coverage area was larger, we selected only the provinces where index testing and index-EPOA were consistently implemented across the entire period of analysis.

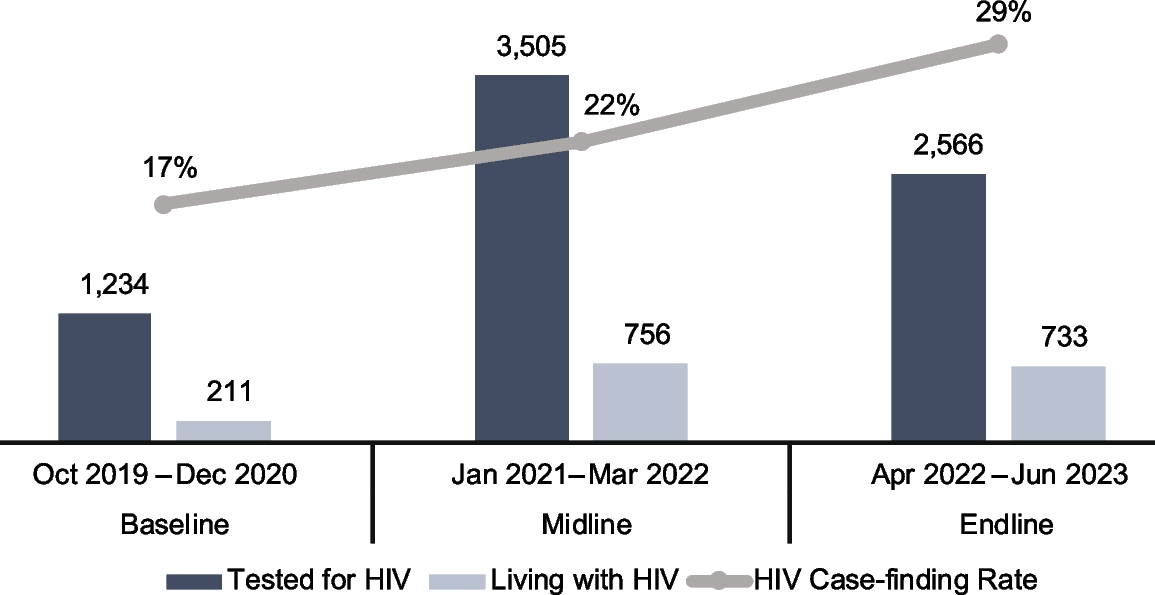

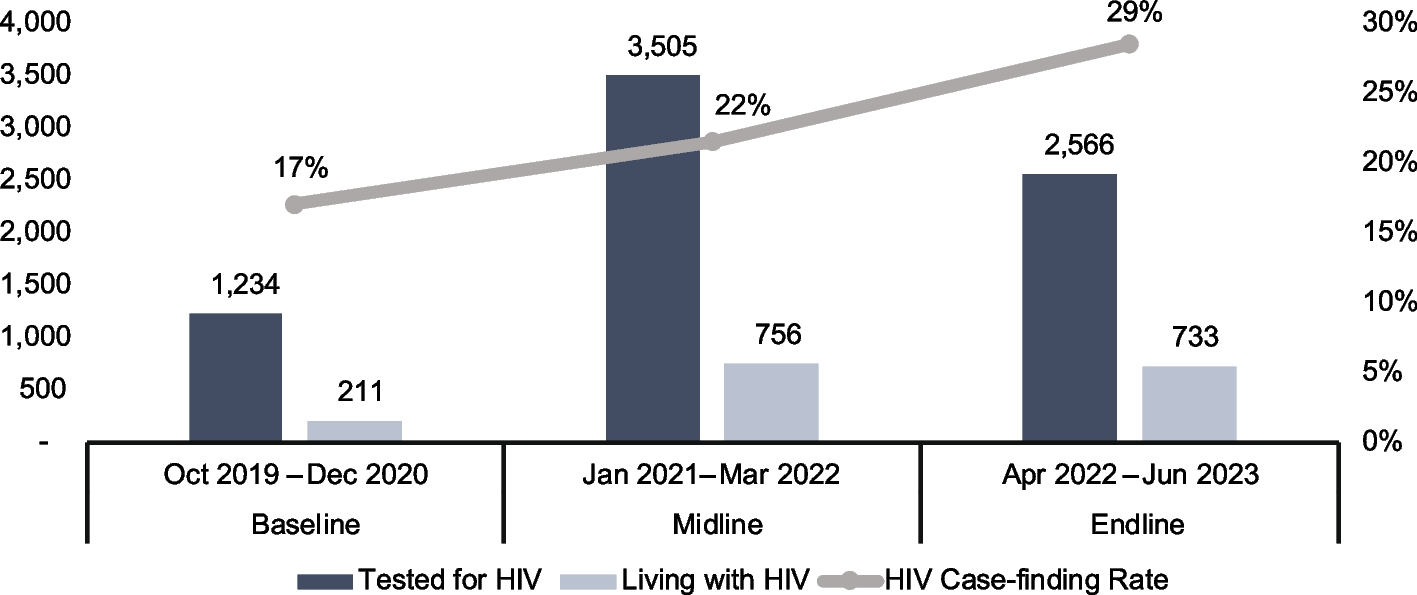

We accessed the program data on November 22, 2023, for three program reporting quarters: baseline (October 1, 2019–December 31, 2020), midline (January 1, 2021–March 31, 2022), and endline (April 1, 2022–June 30, 2023). We compared the number of Haitian migrants and individuals of Haitian descent living with HIV identified through the standalone index testing modality to those identified through the integrated index-EPOA modality from baseline to endline. We also compared case-finding rates from standalone index testing versus index-EPOA before implementation of the intervention integrating EPOA into index testing (at baseline) and after implementation (at midline and endline).

Participants

The program participants whose data we analyzed were Haitian migrants and individuals of Haitian descent served through HS3 and EHSEC. Individuals were classified as Haitian based on self-identification as Haitian migrants (individuals born in Haiti to Haitian parents) and individuals of Haitian descent were those who self-identified as born in the Dominican Republic to at least one Haitian-born parent. Inclusion criteria were being ages 15 years and older and index clients or elicited contacts of Haitian migrants and individuals of Haitian descent.

Interventions

Beginning in January 2021, the HS3 project added index-EPOA testing to the existing standalone index testing and standalone EPOA approaches, described below, with Haitian migrants and individuals of Haitian descent at the health facility and community levels. The three approaches were implemented by HS3 and continue under the follow-on EHSEC project. Peer outreach workers and health care providers engaged through the CSO partners provided the testing services. All were speakers of Spanish and Haitian Creole and were trained and accredited by the Ministry of Health. They included various cadres such as nurses, HIV counselors, laboratory technicians, and peer outreach workers.

All HIV testing in the interventions was offered in compliance with WHO’s essential 5Cs: consent, counseling, confidentiality, correct test results, and connection to appropriate HIV prevention and treatment services [20]. The testing algorithm followed the national protocol: The Determine rapid test was conducted first, followed by a confirmatory second test using Unigold for clients reactive in the first test, and then ELISA as a third test if the Unigold test was nonreactive. Both Determine and Unigold rapid tests were procured through the national supply chain system, offered at both the community and health facility levels, used finger prick, and provided results within 20 min; clients were advised to wait for the test results. Blood samples collected in the community for the ELISA test, which was only offered at the facility level, were transported by the project.

For all testing modalities, clients who tested positive were offered ART at the point of diagnosis and in alignment with the national test-and-treat strategy, while those testing HIV negative were offered PrEP and other tools for HIV prevention (e.g., condoms and lubricants).

Index testing

As part of HTS, the project offered index testing to all Haitian migrants and individuals of Haitian descent living with HIV. The index clients could choose from the following options for offering testing to their elicited contacts: client referral (index clients refer contacts to HTS), provider referral (provider reaches out to the elicited contacts directly to offer HTS without disclosing the index client), contract referral (index client agrees to refer their contacts to HTS within a certain period), and dual referral (provider and index client jointly offer HTS to the contacts).

The project ensured that all index testing was provided in alignment with PEPFAR’s Guidance on Implementing Safe and Ethical Index Testing [21]. Index testing was voluntary. Pre- and post-test counseling was provided to index clients and their contacts to ensure their understanding of the benefits and risks of index testing and their rights to confidentiality and autonomy. Written informed consent was obtained prior to testing and elicitation of the contacts. Confidentiality was secured and monitored through provider use of a standardized questionnaire and procedures for inquiring about intimate partner violence [22]. Contacts were assessed for intimate partner violence, and the index client was offered first-line support if violence was disclosed. Lastly, an adverse event monitoring and reporting system was put in place through which index clients could report any negative impact they experienced during or following index testing to the service delivery provider or peer outreach workers.

Index-Enhanced peer outreach approach (EPOA)

The project offered EPOA as a standalone testing strategy [15] and index testing combined with EPOA (hereafter “index-EPOA”), the results of which we report as combined in the analyses presented here. In standalone EPOA, the peer recruiters were trained to identify and distribute coupons marked “EPOA” to peers at high risk within their networks. Peers at high risk were defined as reporting at least one of the following behaviors: condomless sex within the last six months, sex with a known HIV-positive partner, never been tested for HIV, sex worker, man who had had sex with another man, transgender person, or injection drug user.

The peer recruiters received a financial incentive for each Haitian migrant and individual of Haitian descent they had referred to HTS who presented the EPOA coupon; payment of the incentive was independent of the test result. The value of the monetary incentive was determined based on consultation with the Haitian migrants and individuals of Haitian descent.

In the integrated index-EPOA approach, coupons marked “index-EPOA” were issued to index clients who did not want to disclose their contacts during the index testing elicitation process, as well as to index clients with contacts they wanted to notify and refer on their own. Index clients were also offered the option to identify and distribute coupons labeled “EPOA” to other peers at high risk for HIV within their social network who were not necessarily a sexual and/or injecting partner of the index client. Providers were trained how to explain to index clients which coupons they should distribute to contacts (index-EPOA) versus peers (EPOA).

The unique identification code of the index client was printed on all coupons distributed by the index client. Through this system, the individuals accessing the project-supported sites who presented an EPOA coupon were recorded as EPOA clients and attributed to the appropriate index client, while those presenting an index-EPOA coupon were recorded as index-EPOA and credited to the appropriate index client. As with standalone EPOA, an incentive was provided to the referring individual who had distributed the coupon—in this case the index client—based on the coupons turned in by the contacts or peers, irrespective of their test results. The incentives were distributed weekly by the project coordinator in an amount that aligned with the standalone EPOA incentive.

Data collection and analysis

The aggregated data were routinely collected by providers using HTS and index testing recording and reporting tools, as well as the EPOA coupon tracker. As noted above, identification and recording of which HTS recruiting approach had brought in a particular client was determined by the coupon presented, marked as EPOA (standalone) or index-EPOA. Clients who accessed HTS without a coupon and reported having a known HIV-positive partner during the HTS counseling were recorded as having been referred through standalone index testing.

Data were summarized and reported weekly and monthly. Prior to analysis, we disaggregated the data by age, sex, and HIV test result. We calculated the case-finding rate (defined as the number of clients living with HIV among those tested) by testing modality (standalone index and index-EPOA) and the “testing index” indicator. Testing index was defined for standalone index testing as the number of contact clients tested divided by the number of index clients, and for index-EPOA as the number of “secondary clients” who completed testing following social network divided by the number of index clients making referrals/distributing coupons.

For the statistical analysis, the difference in case finding at baseline (prior to the index-EPOA intervention) and follow-up (after implementation of the index-EPOA intervention) was calculated using the Student t-test. Along with the t-test, we calculated the point estimate of the difference in proportions, which serves as the best single estimate of the effect size observed between the groups. To assess the precision of this point estimate, we derived a 95% confidence interval (CI), indicating the range within which the true difference in proportions is likely to fall with 95% confidence. Differences greater than 0.05 were deemed to be statistically significant.

Baseline data consisted of reporting from October 2019–December 2020 (pre-intervention), while the follow-up period post-intervention was midline + endline (January 2021–June 2023).

Data quality

Client information was entered into paper-based index and index-EPOA tools for monitoring and evaluation using a unique identification code based on a 13-digit alphanumeric code and client demographic characteristics. The data entry clerks reviewed the data on the paper-based forms for completeness and consistency before entering them into the electronic database. All data were regularly validated through the project’s established processes for data quality assurance using data triangulation between the paper tools and the electronic database. Built-in validation rules within the database mitigated data entry and transcription errors. At the end of each day, a gap analyzer was run on the database to identify data errors, which were then checked against the source documents and cleaned.

To minimize the risk of misclassification, the clients were identified through geographic targeting for the project services—that is, offering the services at specific locations where the people were primarily Haitian migrants and individuals of Haitian descent. Peer outreach workers were trained on the definitions of client categories, and the project coordinator verified client category data with the clients during supervision visits to the service delivery sites. In addition, prior to monthly reporting, the project team made random phone calls to clients who had accessed HIV testing services as a mean to further validate the data.

Prior to the weekly and monthly reporting, any gaps and outliers identified were reconciled, and data were regularly de-duplicated using the unique identification code. Testing data were also de-duplicated by testing venue to avoid the same client being reported twice when testing at the community and facility levels within the same reporting period. This approach played a pivotal role in mitigating the risk of data fraud associated with index-EPOA, given that it is an incentivized testing strategy, as well as ensured data quality and integrity. As part of data quality assessment, the project also placed random calls to the contacts to verify their identity and use of HTS.

Ethical considerations

The request to use HS3 and EHSEC programmatic data for this analysis (“Maximizing the use of routine data in the PEPFAR-Funded Enhanced HIV Services for Epidemic Control project in the Dominican Republic: going beyond bean counting,” reference no. 2136207–1) was reviewed and approved by the Protection of Human Subjects Committee at FHI 360 and given a determination of not human subjects research; given this determination, it was not reviewed by a local ethics committee. All data included in our analysis were aggregated, deidentified data extracted from routine project performance reports. These reports were prepared and used for routine program monitoring and improvement and are publicly available. No additional data were collected from clients beyond those for the routine programming reporting. Per Dominican Republic government guidelines, all program clients signed consent forms which covered data collection and the use of programmatic data for analytical purposes; these forms remain in their client files. Also, per government regulations, is not necessary to obtain parental consent for individuals ages 15 and older. At no point did the authors have access to individual-level data or personally identifiable information.

All clients received pre- and post-test counseling before and after the HIV testing in alignment with national guidelines. All HIV testing was voluntary and provided only upon written client consent. Clients who tested HIV positive were offered index testing counseling. All tests were conducted by providers trained and certified in HTS and in accordance with privacy, confidentiality, safety, and security standards.

An electronic system to monitor potential adverse events was established for documentation of coercion, violence, and any other negative effects occurring during or following standalone index testing and index-EPOA. During pre- and post-test counseling, providers explained to clients the process for reporting events potentially associated with routine testing, index testing, and index-EPOA. The index clients, contacts, and referred peers were given the peer outreach worker’s contact information and advised to reach out in the case of an adverse event; the peer outreach worker would report the adverse event to the HTS provider; and the HTS provider would inform the project site coordinator, technical director, and chief of party, who would launch an investigation. The project site coordinator was responsible for documenting the case in the electronic monitoring platform and linking the client to the relevant services.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content