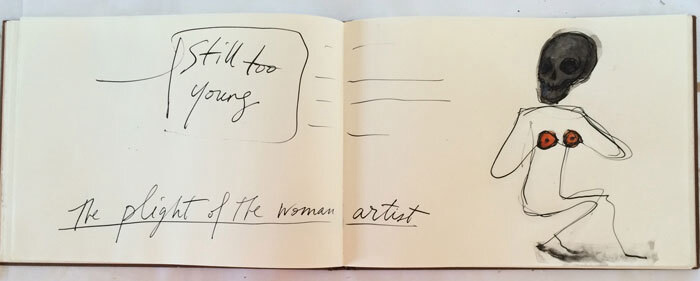

“At one point, I did these drawings of the three ages of the woman artist,” Mira Schor tells me over the phone. “1) Young and Naked 2) Still Too Young—which runs from 35 to close to death—and 3) Not Dead Enough.” At 73, the artist and writer is squarely in the second stage of the ironic career arc she delineated, and coming down from a year that has (re)introduced her visceral, category-allergic practice to the world.

In 1985, just shy of a decade after her involvement with CalArts’s Feminist Art Program and participation in the seminal show “Womanhouse,” Schor was back in New York and painting, a medium she had previously left behind for explorations in paper and installation. That year, she published “On Failure and Anonymity,” an unsparing critique of the MFA pipeline, the male-dominated market, and the romanticized idea of the artist. “The basic fact of the artist’s existence remains that no one asks you to do whatever it is that you do,” Schor writes in the essay, “and just about no one cares once you’ve done it.”

Thirty-nine years later, more people care about Mira Schor’s existence as an artist than ever before. “Moon Room,” her lauded exhibition at Paris’s Bourse de Commerce last fall, spawned a frenzy of interest in Europe, cemented with a new solo presentation at Marcelle Alix, on view through mid-May. “Wet,” a concurrent show at Lyles & King, marks her New York homecoming, with works spanning the ‘70s to now.

When I ask her what this renewed attention has meant to her, she doesn’t miss a beat. “I wouldn’t say there’s been a resurgence of my work: I think it’s a surgence. The last show I had had was at a gallery called Marvelli, in 2012. When it didn’t do incredibly well, Marcello [Marvelli] retired from being a dealer, and I was back where I started. I thought, Oh fuck it. Then I met Isaac Lyles in 2015. He really committed himself to my work, and gradually we’ve been documenting work going back through time.” Below, the indelible artist looks back on where her career has taken her, and why she can’t wait to focus on what’s next.

CULTURED: You have two concurrent shows up right now—“Margin of Safety” at Marcelle Alix in Paris and “Wet” at Lyles & King—along with a show you curated of your mother’s work, “Resia Schor: War and Peace,” opening at Satchel Projects this month. What was it like to delve into your late parent’s practice?

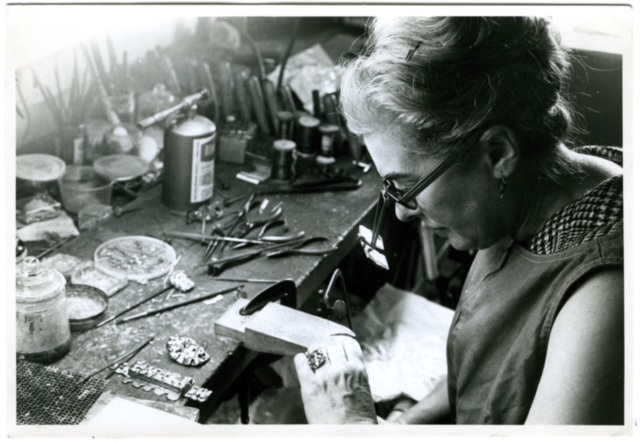

Mira Schor: My mother was [first] a painter. When my father died, she quite rightly figured that she couldn’t support two children with painting, so she thought, Why don’t I sit down at his desk and just finish the small pieces left on his work table. She really found herself in a sense; the resistance of metal turned out to be a magical space for her. Nothing could redeem the catastrophe of my father dying, but in another way it redeemed the lives of me and my older sister to suddenly have this mother who was doing this beautiful work that we loved and with which she supported us. She really was a true model of feminism in action and an American success story.

CULTURED: Do you remember what it was like to watch her work, to see her take up those metalworker’s tools?

Schor: From childhood, I watched both of my parents work. They worked at home, so I literally could just stand at my father’s desk and watch him work, and I could see her painting. But watching her work when I was 13 years old onwards was very impressive. She would solder her works with this contraption that she attached to our gas stove in the kitchen with a sort of pipe that funneled it into a welding tool, and she’d have these goggles on and be covered with soot. I would think, That’s my mother, she’s working with fire. She really believed in the daily practice of art. There was no such thing as waiting for inspiration. For years I really felt those words were in my head—that you didn’t hang around waiting for something, you did something.

CULTURED: If we turn to the Marcelle Alix and Lyles & King shows, how do you see them in conversation?

Schor: What really links them together are four works in each gallery, one each from four series from 1975 to present. Marcelle Alix called their show “Margin of Safety,” and that’s based on a multi-canvas work from the early ‘90s. In New York, we’re showing the sister of that work. They both spell out “Margin of Safety” between breasts sketched on linen. A friend of mine at the time had lumpectomies, and she explained to me that when you have cancer surgery, the surgeons create a margin of safety by taking some healthy tissue around the tumor. I was painting language and always looking for language that had more than one meaning or more than one interpretation.

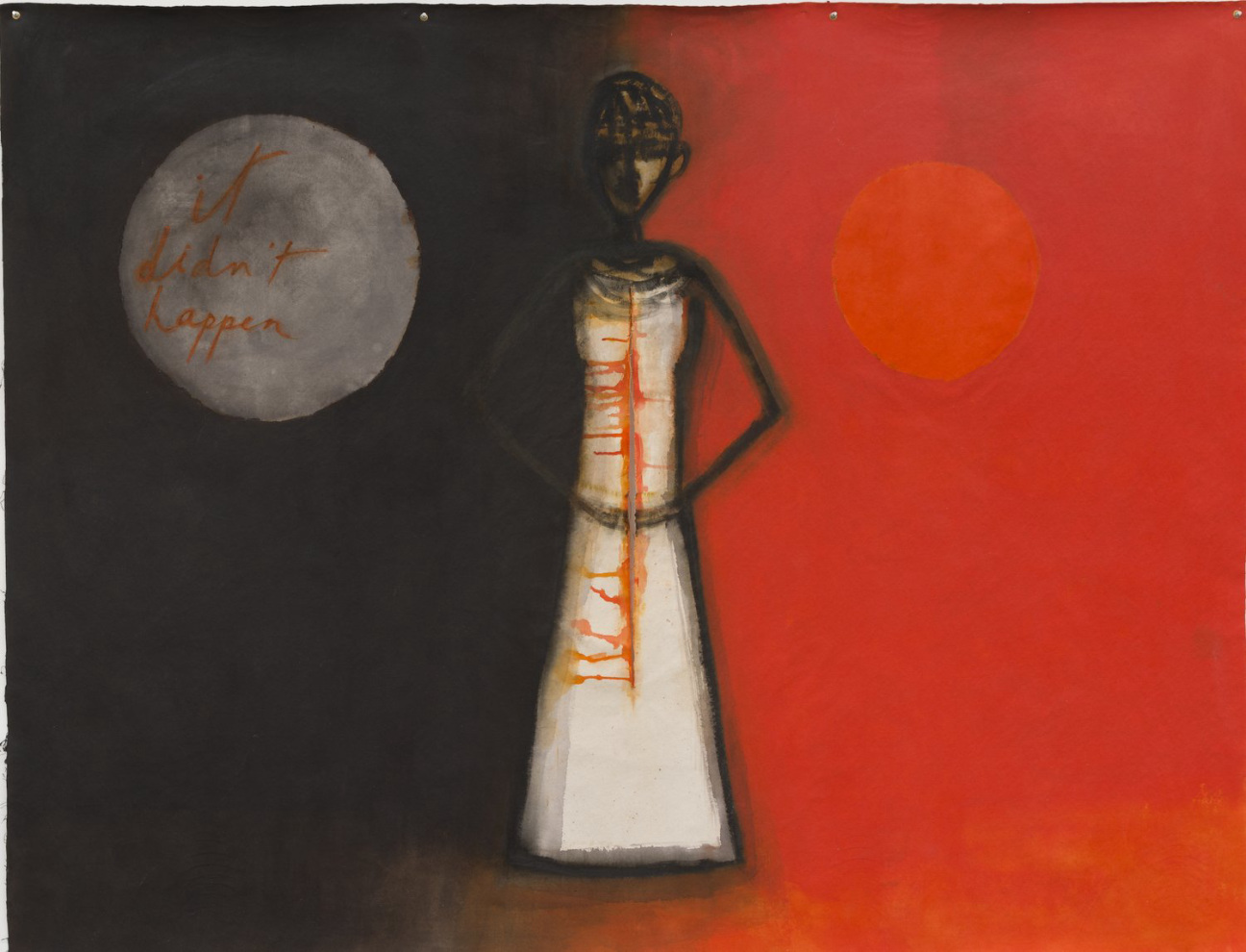

There is also a life-size paper dress in each show. Each is from the first group of life-size paper dress works I did, so they’re both from 1975. Then there will be one new work from a group of three large canvas paintings I did this winter. They’re very iconic and simple in a way. Each one has a figure in the center, and in the center of the figure, which is also the center of a painting, there’s a vertical tear. The one that’s up at Marcelle Alix is called Torn. The one that we’re showing in New York is Torn (It didn’t happen); it has two orbs, and in one of them is written “it didn’t happen.”

CULTURED: Can you tell me a bit about the ecosystem in which the most recent work was made?

Schor: They were made under quite a fair amount of pressure on myself to get them made so that we would have a choice to have new work in each show. Preparing for the show at the Bourse de Commerce was really, really demanding because in a way I was the only person who could interpret what I was presenting to them and knew what the work was about because nobody had ever seen it. When I got back, I was just super exhausted. I couldn’t really paint. I was spending the summer in Provincetown, where I’ve been going to since I was 7, and I just sat down to make a birthday present for somebody. That little drawing allowed me to [depict] the simplest thing that goes back to my childhood: a woman in a dress in a room.

I started working with some inks that were very exciting—purples, oranges, and pinks. It was the summer of Barbie, so the first one was very pink. When I came back to New York from Paris after my Bourse show, that was what I was doing. I’d gotten a little notebook with very nice handmade paper at Sennelier in Paris. I noticed it was held together basically by a string, so I just pulled one page out and left a tear. I thought, Well, I’m gonna use that tear to draw on both sides of the paper and emphasize the slit with red or orange ink. Not all the works in the Lyles & King show have red in them, but I think it’ll be noticeable that it’s a very powerful color within the selection of the work … There’s a very strong sense of embodiment, especially of the female body. The redness of blood was certainly a source when I was in my 30s and my own body was producing this matter that was very much like oil paint. Now, I think it’s more coincidental.

CULTURED: The Lyles & King show takes the same name as your 1997 book. Are there any bridges between the two?

Schor: The way in which some of the work in the show is connected to Wet: On Painting, Feminism, and Culture is that it was done at a certain time when I was asserting that painting was a space for a feminist voice. It may be hard to believe because now there’s so many women painters, but in the ‘80s in particular there was a lot of experimentation with other materials. During most of the ‘70s, I moved away from traditional painting towards things that were things, like objects made of paper.

In the ‘80s, I was back in New York, and at that time you’d have these major exhibitions and the only painters would be German, Italian, and American men. They could do big things with lots of color, but women were pushed toward photography and other media. The other thing that happened during this crucial time period was the change in feminism itself towards the critique of essentialism. Meanwhile, people like Benjamin Buchloh and people who were writing for OCTOBER were basically disgusted by the recourse of painting to an essentialist state. That’s where I entered that discourse. I started writing, and I started painting in oil. It was completely simultaneous.

CULTURED: Where do you see painting going in 2024? Are there artists that you’re watching or in dialogue with right now?

Schor: More than at any time since I was a child, I’m working on my own. The force to continue making art is coming from myself as opposed to really being driven by influence. There’s an interiority or reliance on everything I’ve ever seen right now, even going back to the origins of my own work. A lot of contemporary art is being made in a variety of styles of which there is now an encyclopedia that everybody can pull from. People are working from established styles or ways of working, and, beyond that, there are a lot of identities that people are working from. Everybody’s in their own identity, and the art market is interested in whatever it’s interested in.

CULTURED: After opening these exhibitions, what else are you looking forward to returning to in your practice?

Schor: I’m looking forward to not having pressure on me so that I can have three days in a row where I don’t have to write something or answer emails! What I really want to do is write a cultural biography of my parents. I live now where I grew up, and the apartment is filled with my parents’ work, a lot of my work, and all my childhood things. I just want to do an inventory and use the idea of an inventory as the springboard for short paragraphs or short essays. Maybe that’ll end up being a book.

I do want to continue the large paintings. The recent paintings in the Bourse de Commerce show have a figure which is based on a group of clay sculptures [of dancing and singing women] I made when I was 10. I’m looking at them now. They survived because they never left this apartment. When I moved in, I put them in a slightly more prominent place and thought, I’d like to do a painting of these. Then I thought, Maybe I’ll try to do a couple of sculptures around the same scale for myself.

This past year, I’ve not felt well. Being the friend of artists who were older than me, like Leon Golub and Ida Applebroog, both of them had to stop doing certain kinds of work in their 70s because they just couldn’t do it physically. Neither of them could get on the ground and scrape paint anymore. That’s the other thing about the story of the older woman artist finally getting her due. The tragedy of it is often you can’t really use that. You can’t use the newfound success, particularly financial success, because you’re just too old.

Very few people live as long as Louise Bourgeois, who was able to use the success to do amazing work for another 20 years, work she couldn’t have had the opportunity to do before that success. It’s been a marathon, and the restorative part is the life of the studio, which is what I talk about in “On Failure and Anonymity.” That’s the most real space. Creativity—not to be corny—is a bit like water that flows where it wants to go, which may be a bit off course. It moves and you have to follow it. Whether it’s writing or art making, you think, Why don’t I try this? And then you follow that impulse.

“Wet” is on view through May 4, 2024 at Lyles & King in New York.

“Margin of Safety” is on view through May 18, 2024 at Marcelle Alix in Paris.

“Resia Schor: War and Peace,” curated by Mira Schor, will be on view from April 11 through May 11, 2024 at Satchel Projects in New York.