How does a social media platform go mainstream in the 2020s? For the last several years, tech companies have tried to launch supposedly cutting-edge platforms – ones they tell us will shake up our digital consumption – which have overwhelmingly, if not universally, failed. There was BeReal, the anti-Instagram that got you to take a picture of yourself and your surroundings at a randomly prompted moment, which burned out after brief popularity in 2022; Threads, Meta’s Twitter alternative hoping to capitalise on Elon Musk backlash, has been more or less in freefall since it launched in 2023.

The biggest failures, though, have come from apps pitching a dedicated political space, such as Parler, the now-shut down “free speech” microblogging site, once nearly owned by Kanye West, and Truth Social, Donald Trump’s own Twitter alternative built after he was banned from the platform in 2021, which is less of a social network than a Trump press release forum and lost over $400 million last year. This graveyard of failed apps has made new social platforms some of the riskiest, most guaranteed failures in tech.

But recently things have begun to shift. Sites like BlueSky (a less hateful version of Twitter) and Rumble (a more hateful version of YouTube) are succeeding by offering something explicitly narrow: a place where getting to exist in a small political bubble is the USP.

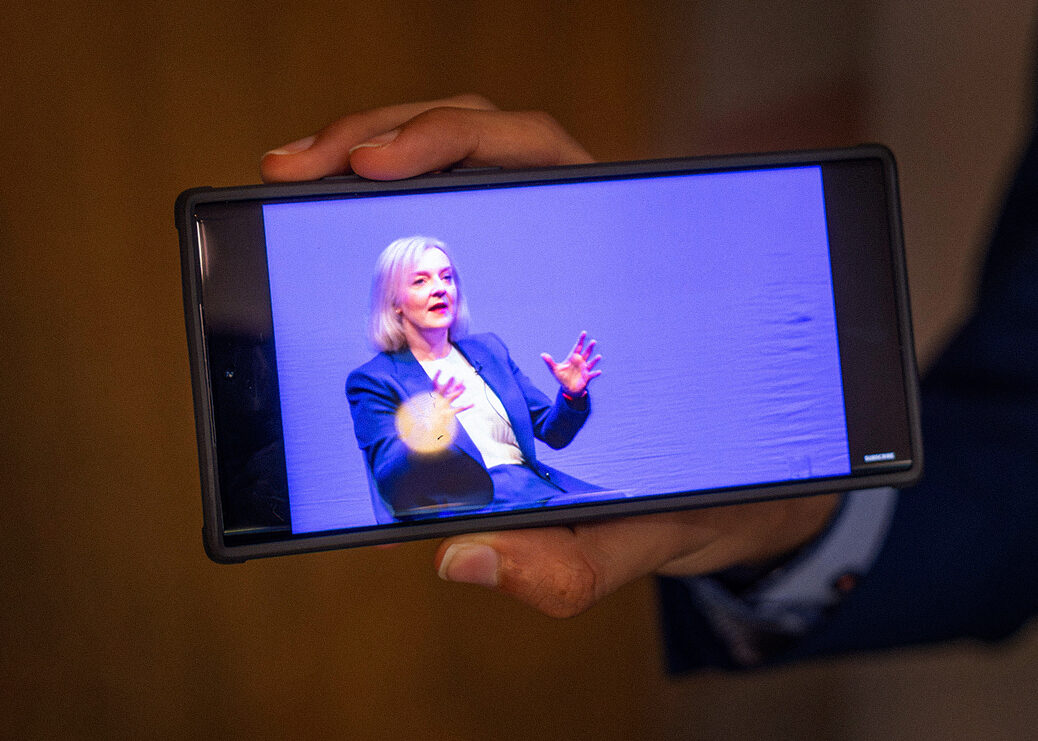

We are seeing a changing social media landscape where users are now seeking platforms promising the opposite kind of audience social media has traditionally sought to have: niche, dedicated markets rather than something akin to a digital, global town square. It is likely with this in mind that, last week, the former UK prime minister Liz Truss announced that she would be testing the popularity of niche: by launching her own free speech-focused social media site.

Speaking at a cryptocurrency conference in Bedford, Truss said that “the elite” had “cut [me] off at the knees” when she became PM. “What I’m now thinking is we need a media network to be able to communicate to people, to be able to have a grassroots movement that is actually really demanding change of our leaders,” she said, adding that she felt certain political topics were “suppressed or promoted” by the media. “This needs to be actively fought and what I am doing is establishing a new free speech network, which will be uncensored and uncancellable, to actually talk about the issues people don’t want to talk about.”

This is yet another attempt by Truss to enter the American political sphere, having spent the last few years trying desperately to align herself to Trump and the American right to no real avail. (She is of course also not the first UK political figure to launch their own social media platform: former health minister Matt Hancock created an app for his constituents called Matt Hancock MP in 2018, which has since shut down.)

Whatever platform Truss is cooking up is not going to be the future of any faction’s online diet, but it’s wrong to think that fractured, politically-specific platforms can’t work in 2025. Now, in our increasingly polarised political environment, actual echo chambers are beginning to look more appealing to consumers who are no longer looking to rub shoulders with every kind of person online.

Rather than to become the next TikTok, Instagram or even Twitter, tech companies are realising there’s money to be made by courting smaller, ideologically-motivated audiences who are so committed to their politics – and certain political figures – that they will use and even pay for dedicated social media sites. Many of these sites, like Rumble, have even explicitly shifted their branding to appear more boutique, moving from describing themselves as a YouTube alternative to instead pitching themselves as a free speech vertical. Platforms no longer need to be the place where everyone is, but simply a place where you will instead only find specific people – and only those you already agree with.

We may be at the start of a new era of social media defined by a fractured, mosaic landscape, where we are offered an enormous amount of content that validates our pre-existing beliefs. But it feels more likely that, whether or not we continue to have a few big platforms or a spread of tiny, specific ones, the era we are entering will be remembered as narrow; as reactionary.

[See more: Nigel Farage’s mayday alert]

Listen to the New Statesman podcast

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content