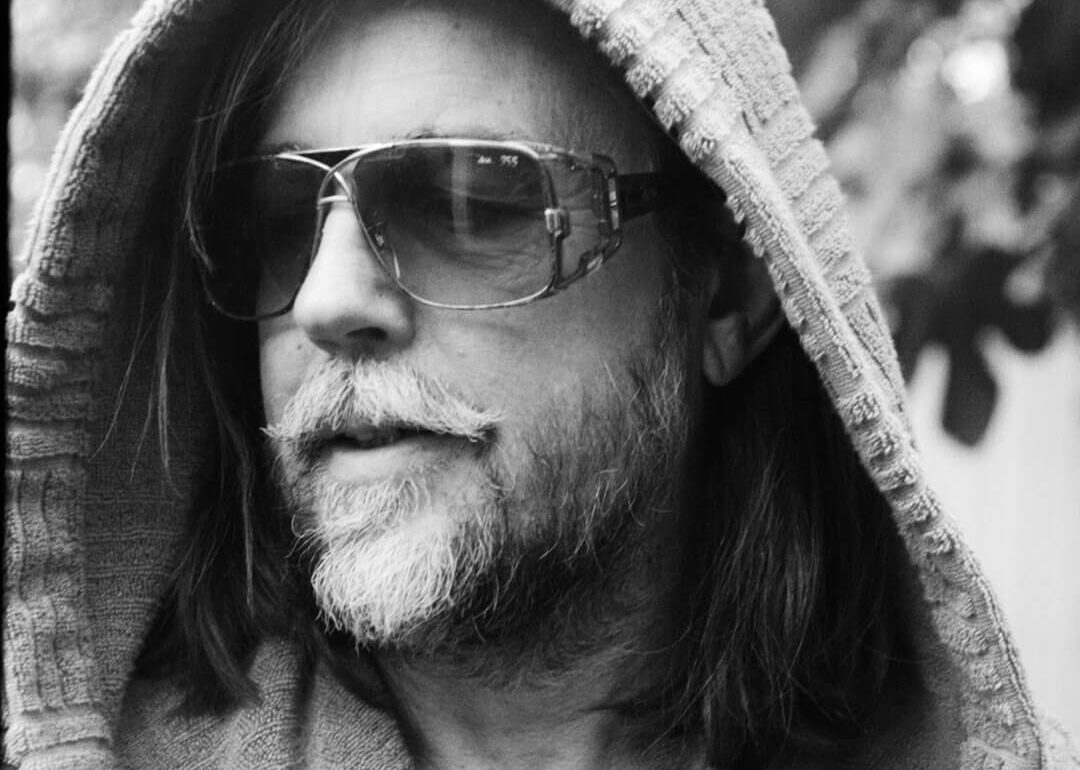

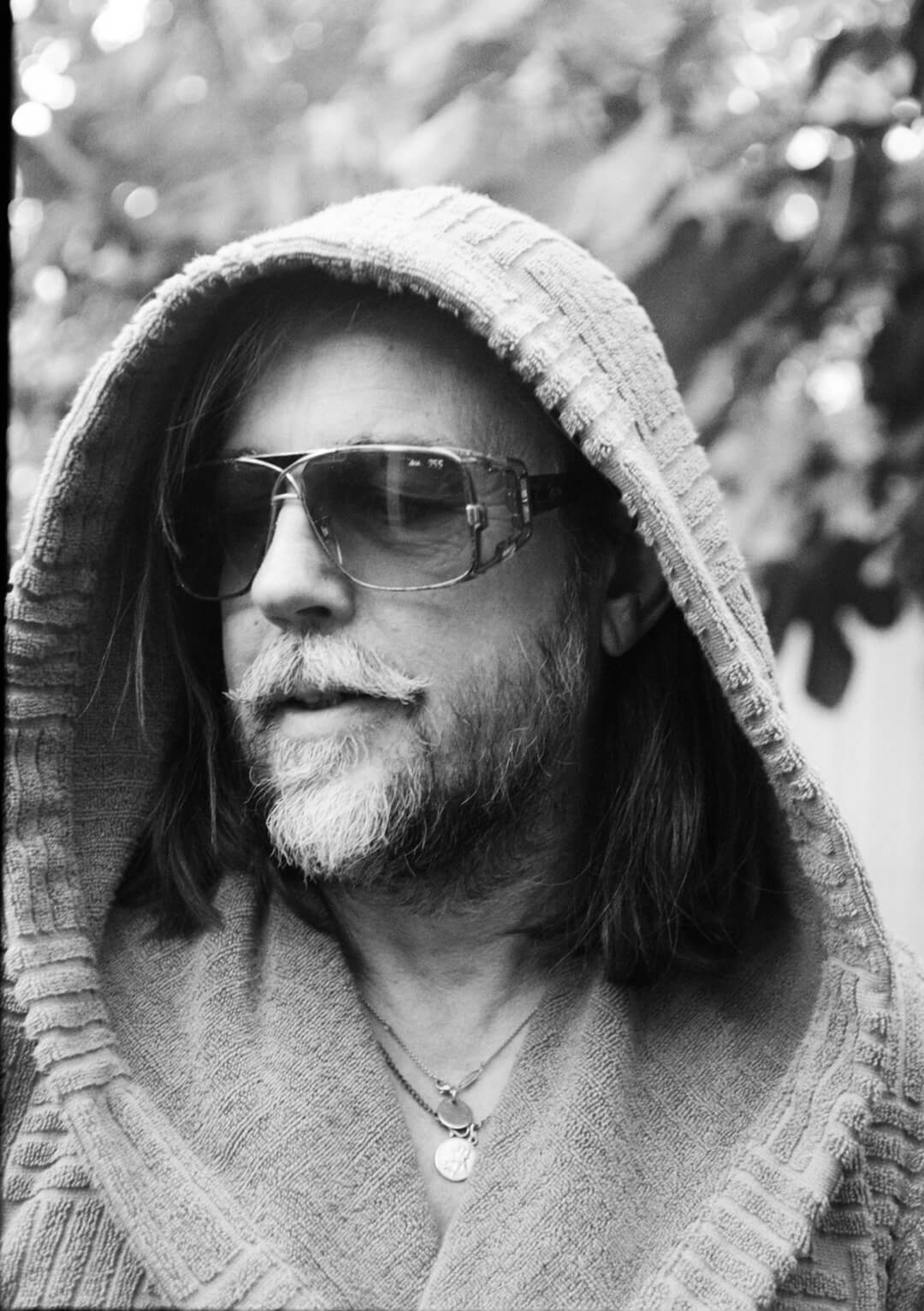

Turner Prize-winning artist Mark Leckey, born in Birkenhead, United Kingdom, is drawn to liminal spaces where art forms and social realities intersect. He describes this as a “grey space” that transcends traditional categorisations of art, music, theatre and dance, allowing him to synthesise elements and dissolve boundaries. Known for his multidisciplinary practice, which spans film, sound, sculpture and performance, Leckey’s works encourage viewers to consider the nuances of popular culture, technology and class, embodying his belief in art’s ability to metabolise and subtly reflect societal conditions to spark new conversations. His artistic explorations have been exhibited globally, with notable solo showcases at Tate Britain, MoMA PS1, Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK), Denmark, Kunsthalle Basel, and Haus der Kunst. More recently, In The Offing (2023) opened at the Turner Contemporary in Margate.

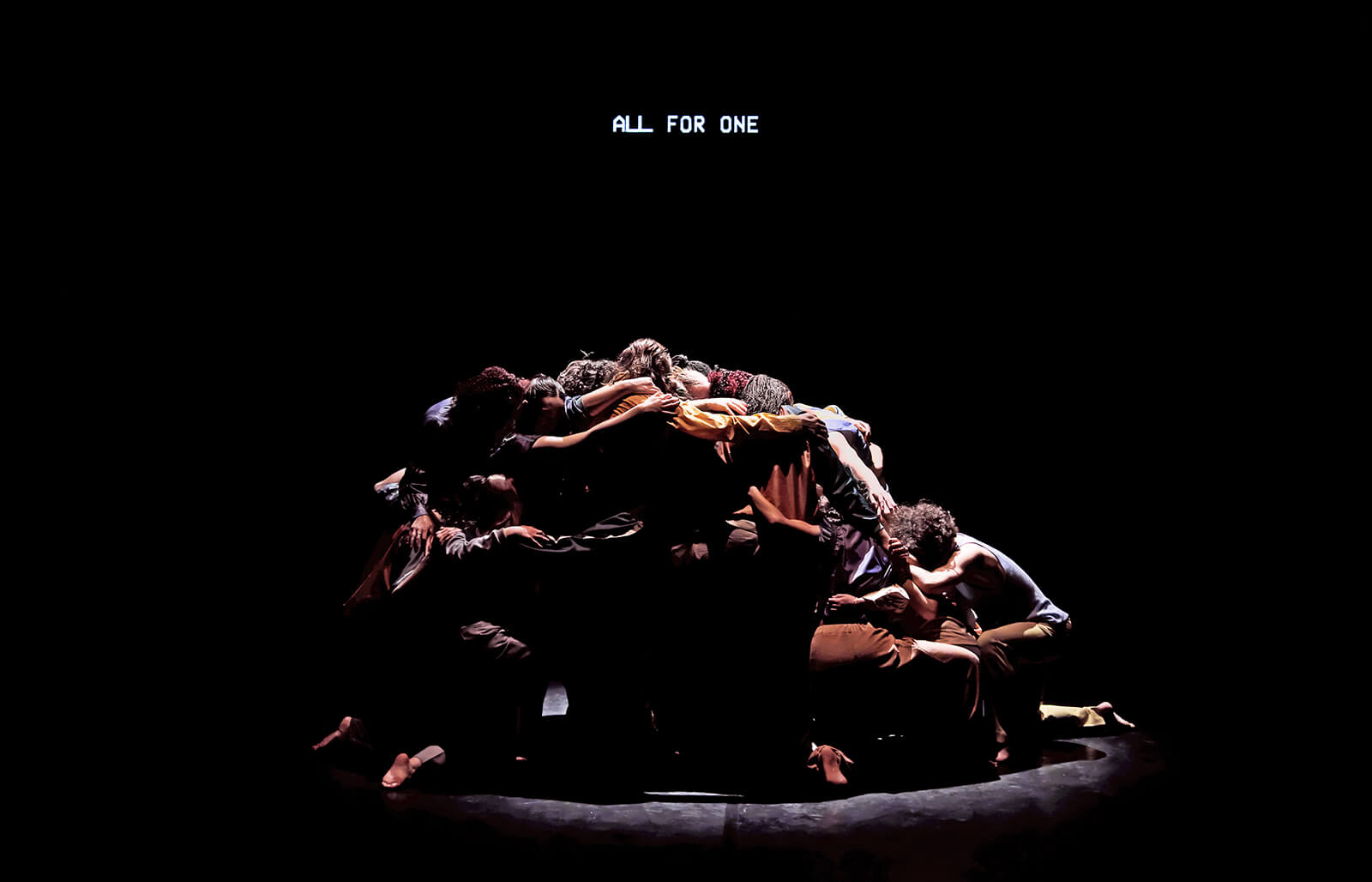

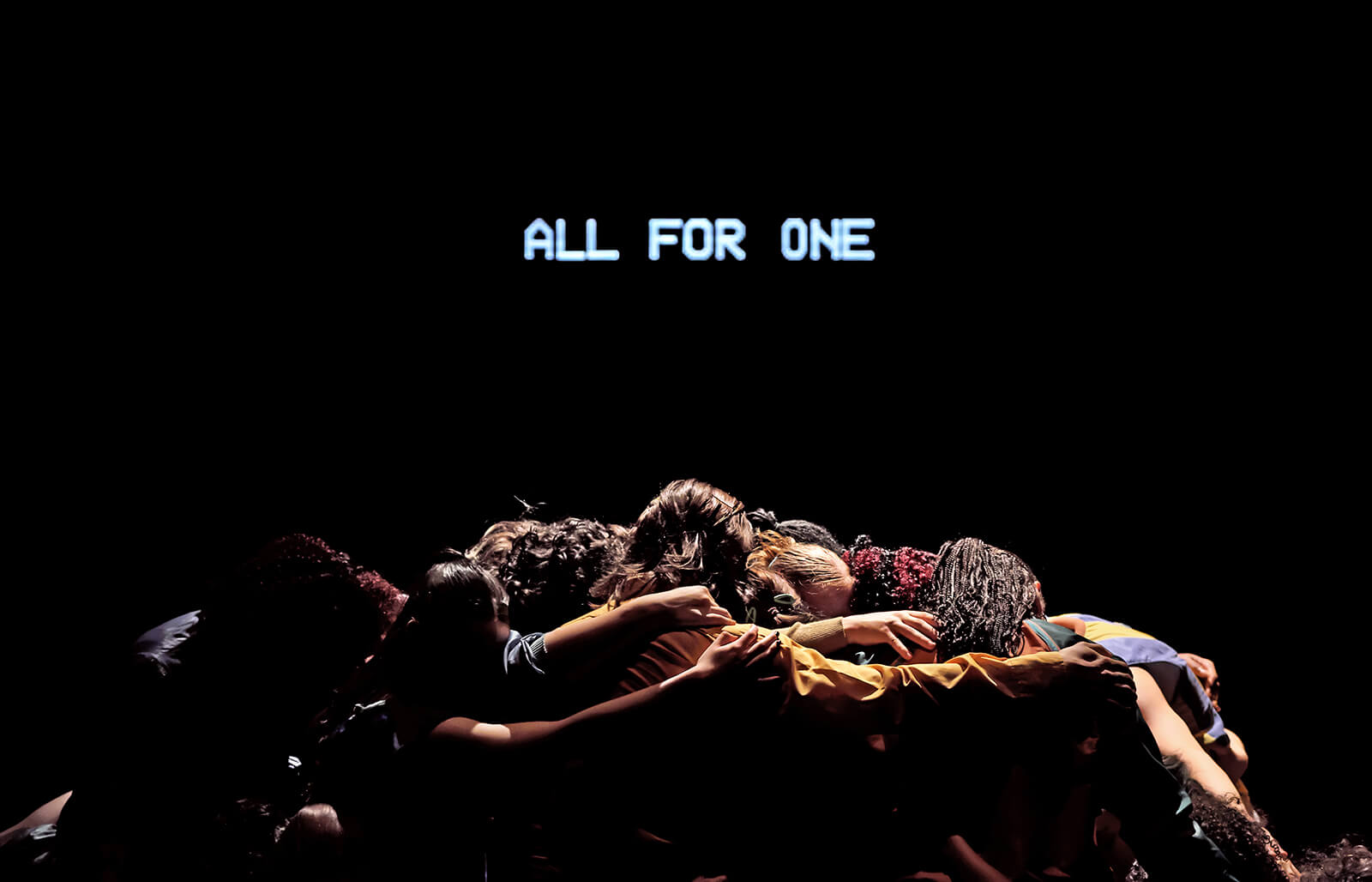

Leckey’s latest venture is a collaboration with visionary choreographer Oona Doherty, the Guest Artistic Director of the National Youth Dance Company (NYDC), run by Sadler’s Wells. He has created the sound for Doherty’s latest work, Wall, which explores the intersections of youth culture, national identity and collective expression. Wallwhich premiered at Leeds Playhouse, is currently on a nationwide tour. It will debut in London at Sadler’s Wells on Saturday, July 13, then continue to Bold Tendencies and CAPA College, AMATA Arts Centre, DanceEast, Latitude Festival and Curve. The project reflects Leckey’s long-standing fascination with dance, evident in his 1999 film, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, which captured the pulsating energy of youth culture through the movement of bodies and sound.

Here, Leckey draws inspiration from Doherty’s exploration of collective expression. An archive of stories from young dancers and their families resonates with Leckey’s focus on social and cultural narratives. Doherty’s choreography, a dynamic fusion of repetitive forms in the NYDC’s performance, further influences his dexterous approach to the evolving soundscape. His technique features multi-layered sound effects and a vocal archive of diverse British experiences, paired with a contemporary musical reinterpretation of Union, Jack by Big Audio Dynamite. As a result, when audiences engage with Wall, they experience a complex, multi-faceted performance. The show features the NYDC’s new cohort for 2023/24 – 32 dancers, aged between 16 and 24, from 21 towns, cities and villages across England. Wall asks them to address the question, “If you spoke to Britain, what would it say?” Their answer will undoubtedly impact our understanding of society and ourselves.

Excerpts from a conversation with STIR:

Ayesha Adonais: How would you describe your practice?

Mark Leckey: I make art because images have always had a powerful effect on me, and art allows me to understand what that effect is. As a part of this process, I can stop the flow of images and examine them and my feelings. It’s a way to explore why they affect me and my psychology. I show it to others, asking if they feel the same. Then I show it to other people and say, does it do the same to you, too? Do you feel the same way I do? It becomes a ritual when people say, “Oh, yeah, that does the same to me.” Then, you have a shared understanding of the thing. Ultimately, that is what I want when I finish or have a show; I want people to come up to me and say, yeah, I felt that. It’s like music. You’re trying to reach people; you are trying to communicate. My art communicates interior things, puts them out there and makes them visible.

Ayesha: What drew you to collaborate with Oona Doherty on Wall?

Mark: I was a fan of Oona’s work. If I see someone who comes from a similar background and they’re using the language, the intelligence of that background and not making it a cliche or something that’s easily transmitted. At the same time, it is transmitting something familiar or common or whatever. But they do it in a more challenging way. You find a lot of stuff that comes from the idea that working-class culture has to be quite basic to reach a wider audience and it doesn’t want to get too clever. It doesn’t want to be too smart. However, the kind of working-class culture I grew up in was both local and experimental. It can do both and the best of it does both. That’s what I saw in Oona, watching Oona dance. You ask, how are you doing that? Where’s that coming from? Could I understand where it’s coming from? How did you make that jump into something that seems totally of this moment but alien somehow? Weird, unseen, new.

Oona’s body would form this sentence. You watched that ripple through and it was fantastic to see how that got translated into the dancers.

– Mark Leckey

Ayesha: How did your collaborative process with Doherty work? How did you use sound to reflect aspects of British culture and social commentary?

Mark: In the initial process, Oona interviewed the National Youth Dance Company and their parents. I was supplied with a huge database of these conversations. They were asked a series of questions. Where are you from? What was your first experience of music? Your first social experience or cultural experience? Experience of being in the group? What was it like back then? What do you think of Britain now? People came from different backgrounds. All over the world, really. So, the responses were amazing to listen to. It’s such an incredible archive. Beautiful.

Ayesha: How did your respective artistic visions influence each other?

Mark: The inspiration for the music came from Oona, suggesting a track by Big Audio Dynamite called Union Jack. She wanted me to interpret it. The challenge was making it 50 minutes long because the longest track I had made was 15 minutes. Oona had to go into the first rehearsals with the basic bare bones of an idea. I got help from friends because it was too much for me to do alone. Shamos and I worked together with a musician called Julian on our interpretation. It’s not sampling. It’s working with the spirit of something. It was very collaborative. I wouldn’t say it’s my music. There’s me, Luca, Shamos and Oona, inspired by Big Audio Dynamite. It was a collective effort with parts that worked and others that didn’t, adapting to the dancers’ energy. I had a very easy job. What they had to do was much more demanding and complex. We created something dynamic and evolving with the dancers. Oona took our output and continued working on it in rehearsals with Luca Truffarelli.

Ayesha: Were there specific sonic choices you made to amplify the themes in Wall? Could you give an example?

Mark: One of the things I like to do is to take voices and cut them up into something more rhythmic and musical. I was in more familiar territory then. I was making things into snippets and soundbites to integrate them into the music and build up almost like a cacophony of voices or a chorus of voices. It builds up to include what Oona wanted, like the sounds of a wall collapsing. I love sound effects. I had all these kinds of sounds of walls collapsing. I slowed a lot down, so it sounded full of bass. So you got this big boom, these big explosions of collapse. Then, the idea was to build it back up. By the end, the song returns and is quite joyous and energised.

How are they processing the world as it is now? How are they finding gaps and spaces where they can be creative and flourish? That’s what still interests me now.

– Mark Leckey

Ayesha: How does your use of sound contribute to making Wall engage with the physicality of dance?

Mark: The rehearsals were a great experience to watch—the energy and inventiveness of the dancers. Nothing beats a group of young people doing something together. It’s a fantastic thing. The great thing about being in rehearsal is seeing Oona give the dancers exercises to do and say that at the end of an exercise, you could introduce something like this. Her body would form this sentence almost. You watched that ripple through and it was fantastic to see how that got translated. She’s not going to turn them into mini Oonas. She will let them find their sentence and their language.

Ayesha: Do you see this project as a way to break down barriers between art forms and reach a broader audience?

Mark: Not in any straightforward way. Not in any way that could be measured. I am looking for a way to be involved in a developing space between art, music, theatre and dance—a “grey space”. A shared space that is neither. I was reading the other day about art and theatre. They were saying it’s sort of a “grey space”, so it’s neither the ‘black box office’ nor the ‘white cube’. It’s somewhere in between. I’m looking for something similar. I want to be involved in both. At the rehearsals, I saw young people involved in this project who I’d like to see in the art world but don’t. Those who say the art world is not for them. So, how are they processing the world as it is now? How are they finding gaps and spaces where they can be creative and flourish? That’s what still interests me. Music doesn’t have the same barriers and anxieties around it that art does. The best word is that art is becoming slightly more porous, but it’s still quite fortified.

Ayesha: Through Wall and your previous practice, how have you made this connection between art and society?

Mark: I constantly metabolise “class”. That’s part of the fuel—metabolising it to produce energy. For me, I guess that’s still it. It’s a sort of frustration within the art world about its certainties, assumptions and narrowness. Things are changing now, but when I went in, you had to accommodate yourself to it rather than the other way around. All art suggests it’s open, but it is both is and isn’t. Art compels and repulses me equally, so you’re constantly dancing with it. That is what I’m metabolising particularly. Maybe, I think, with Oona as well. I can kind of identify with that. So I’m looking for the most efficient, effective and powerful way people process that stuff. That’s always the joy of it for me. Like I said before. Oh, you got there? You got to that place. Yeah, that’s when I get excited.

Ayesha: Do you believe that art is responsible for engaging with social and political issues?

Mark: I think all art is political. In its being, it is what it does in any form. It speaks of you, your condition and thereby your history. The best of art contains multitudes and it carries that within. It comes from somewhere rooted or out of a particular set of conditions or an environment. I don’t want work to be overtly political or didactic. That is what I like about Oona’s work. It’s implicit in what she does. But not overt; it’s in the background of what she does. You’re always aware of it. But it’s not being pushed to the front. That’s always the sort of work I’m looking for. It’s a wider frame. With art, it’s how you metabolise these things, right? It’s how you process these things. Art, for me, is whatever kind of politics have formed, passed through your body and then returned in this kind of metabolised or digested way, solely yours. But it speaks to the broader political environment.