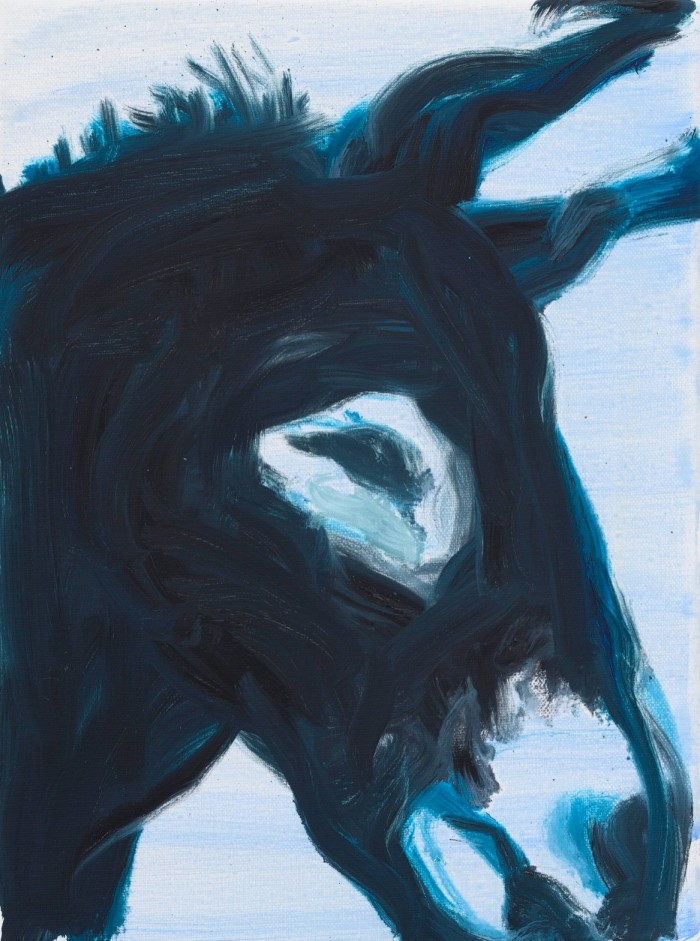

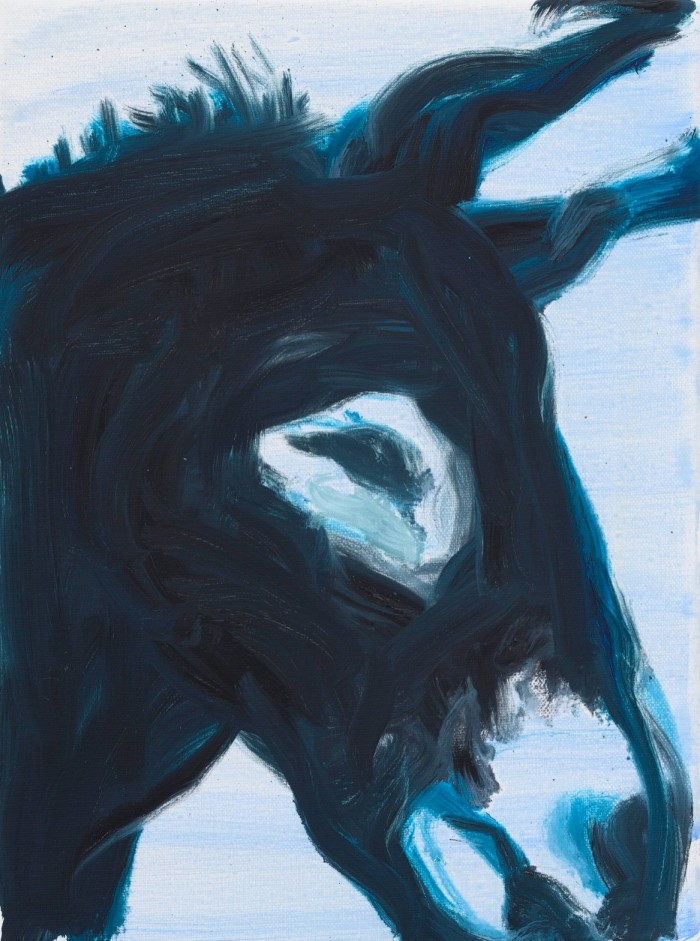

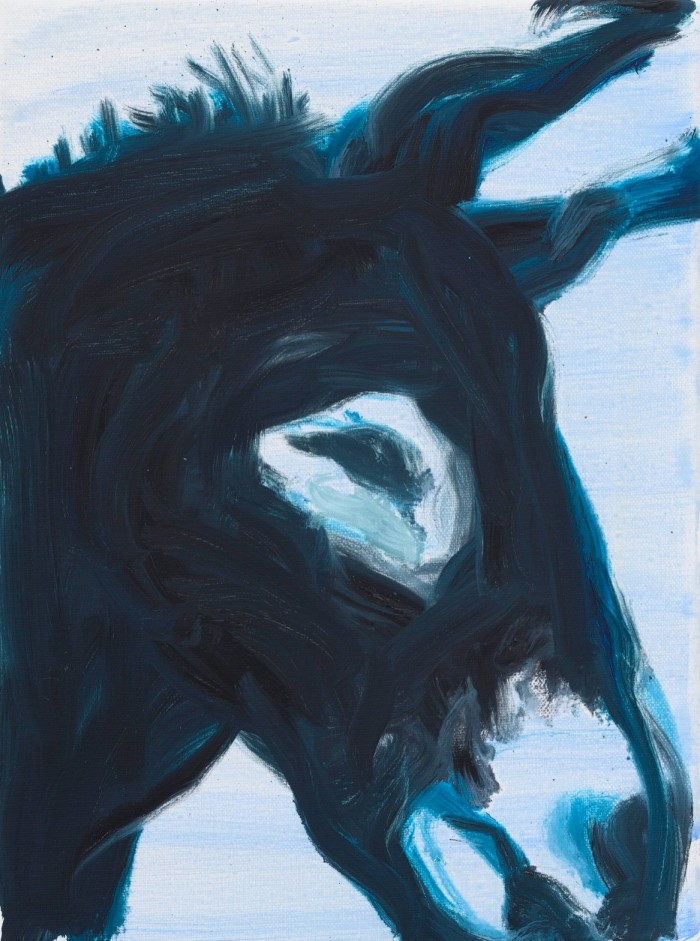

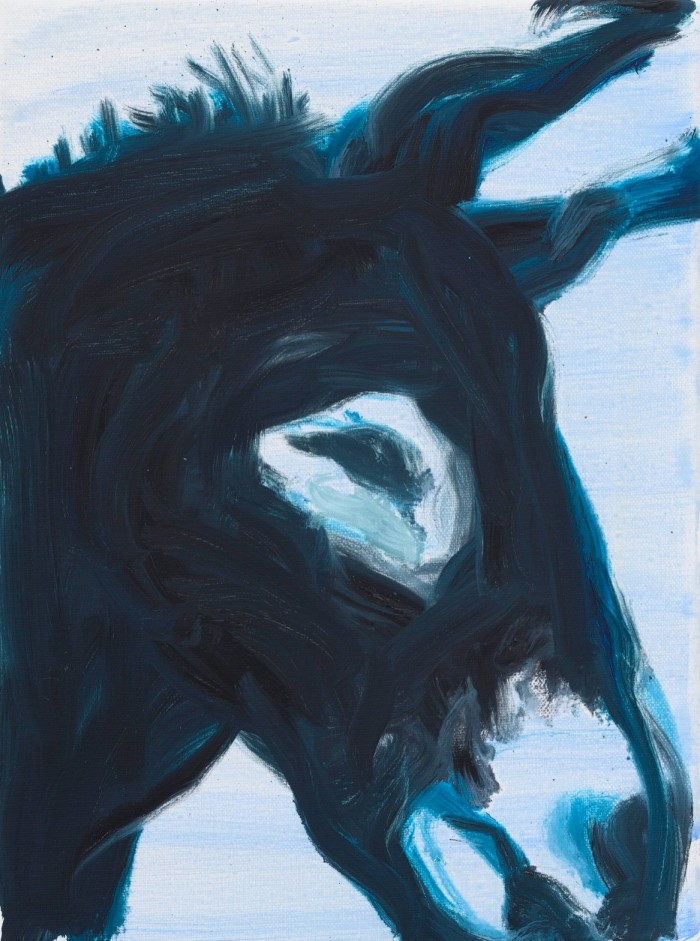

A series of remarkable meetings is taking place inside the elegant, neoclassical interiors of Athens’s Museum of Cycladic Art. In its latest exhibition, Cycladic Blues, ancient figurines from its permanent collection have been placed opposite the cool, psychologically fraught paintings and drawings of the South African-born artist Marlene Dumas.

It has become something of a cliché of contemporary art, to persuade its leading practitioners to enter into “dialogues” with works from the past; but few such shows ask us to leap across five millennia to make their point. The encounter is not an obvious one: the stiff, expressionless statuettes, commonly considered to be the foundation stones of western art, passing their time with Dumas’s nerve-jangling studies of the human figure.

But she disagrees when I point out the apparent incongruity. “I could immediately see the connection,” Dumas, 71, tells me on the day of the show’s opening in Athens. “I always have to tell people that I am not as naturalistic a painter as they may think. There is an aspect of illusionism in my work. I didn’t know [the Cycladic works] very well. I knew that they had influenced so many modern artists. Some of them I could see looked like Picasso. But then I realised of course I had that the wrong way around: the Picassos look like them!”

Neither was she worried about sharing the space, having been “coupled” with other artists before: Francis Bacon, Luc Tuymans. “I am not against couplings, necessarily. But with older art . . . yeah, one has really got to watch out. I was a little scared. So many shows are made because of the idea. But there can be a distance between the idea and the reality. In the end, I was really pleased, and quite touched.”

Dumas’s works seem to have struck a chord with the current human condition. Just a couple of weeks before this week’s exhibition opening, one of her typically provocative, porno-comic works, “Miss January” (1997), sold for $13.6mn at Christie’s New York, setting a record for the most expensive painting by a living female artist sold at auction. The Cycladic Museum’s contemporary art programmer, Aphrodite Gonou, says it is the “unexpected coexistence of violence and innocence” in Dumas’s work that makes it a powerful lens through which to view the museum’s permanent collection.

Dumas responded to the invitation by selecting work, with curator Douglas Fogle, from different parts of her life, which found common ground with the Cycladic pieces. But she is sceptical about there being a “dialogue” between them. “A friend who has just seen it said it is a very beautiful show, but he didn’t believe that they were talking to each other. He said, ‘They have their mysteries, and your best work has its mysteries.’ So they exist in the same space, but not because they are talking!” She lets out a full-throated laugh.

Dumas’s conversation is humorous, slightly mischievous and prodigiously fast-moving. She skips from one theme to another, not always allowing her sentences to unravel fully. There is a parallel here with her working technique, in which she likes to rely on spontaneity and chance, sometimes allowing paint to flow in its own direction. She talks about the current exhibition with a clear critical eye, as if appraising the work of another artist.

“I didn’t plan it like this, but I find it meditative and melancholic,” she says of the show. Did she find it easy to keep that critical distance? “All the artists whom I admire have that ability,” she replies. “Even though I use chance a lot in my work, I have got to take responsibility for it. Do I keep that mark there? Do I remove it? And sometimes you have to look at the work and ask, ‘Is that really true?’”

One of the common themes shared by Dumas and her ancient predecessors is that of eroticism, an interest that is tellingly displayed in her recent, 1.5-metre-high painting “Two Gods” (2021), in which two giant, black phalluses dominate the canvas like a pair of monumental steles. The subject of the work came by chance, she says, when she poured the paint on to the canvas in “two large gestures”, without any preconceptions of what they might be.

“The first one turned into this lovely, gentle shape at the end, and I thought, hmm . . . ” A mischievous laugh. “I didn’t really want to make two phalluses of it, because you know sexual parts are always . . . ” She trails off. “I could have gone in another direction. I sat there for a long time. But this didn’t want to be anything else.”

I ask her to tell me about the painting’s ironic title. “Well, I am not Louise Bourgeois, angry with men in general. [The work] didn’t come out of anger. But that doesn’t mean I wouldn’t like to kill some of the dictators who are around the world at the moment.” She doesn’t specify any further, denying her antagonists the “pleasure” of being named.

Another work, which gives the show its title, “Cycladic Blues” (2020), is a painting of a normally featureless Cycladic head, on which Dumas has placed eyes and a mouth with the lightest of touches. The expression seems to defy easy interpretation. Is it hapless, humorous, happy, sad? “When people want to know what something stands for, well, it doesn’t work like that. I could say anything.” She says the application of the features made for “a very tense day. Because you only have one chance. What are you going to get?”

She pivots abruptly. “I find life is a bit like that. For example, I am sitting here and I didn’t really want to do this [interview]. I was not in the mood. I was in a bad mood. People make me talk so much. But now here we are. And it’s OK!”

One pivot deserves another: I ask about her student life in South Africa, when she says she found it hard to fall in love with classical Greek art. “These life models would sit in these classical poses, and it was nothing to do with what was happening in South Africa at the time. It reminded us of Leni Riefenstahl and [her Nazi propaganda film] Olympia.” Later, when she moved to Amsterdam (where she has lived since the mid 1970s), she says she underwent a “step-by-step” conversion when she learnt that Nelson Mandela and his fellow prisoners on Robben Island had studied and been influenced by Greek tragedy, which seemed to speak to South Africa’s plight.

Was that the moment when she realised the malleability of art, and that it could be interpreted so diversely? And did that idea liberate her? “No! That made me even more worried! Art can be used for anything.” She cites the Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan. “It is not the fault of the art. I would love to make art that was not bought by people I didn’t like, because of their political stance. But it is very difficult.”

Which brings us seamlessly to a final and cheesy question, I say. How did it feel to be the most . . .

“ . . . expensive woman living artist at auction!” she fills in for me. “Ha! That is why I like you. You didn’t start with that question. Well, the auction world is a different world from the art world. But just to put it more lightly, let’s all have a drink to all women artists.” Some people have started to call her a “star” since the news broke, she says.

“When I was young, a ‘star’ meant a film star, but now when I think of stars I think of the stars in the sky, which is where you go when you’re dead. And I don’t want to be that kind of star.”

‘Cycladic Blues’, Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens, to November 2, cycladic.gr

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content