On Wednesday night, Marlene Dumas was newly crowned the most expensive living female artist in the world when her 1997 painting Miss January, featuring a woman with a ghostly white face who’s naked from the waist down, sold for $13.6 million with fees at a Christie’s evening sale. Understandably, the auction house has trumpeted the achievement. And while he work was effectively pre-sold, coming to the block with a third-party guarantee, this is a win by most measures.

Most measures, that is, that don’t account for broader market trends. Consider the fact that Miss January wasn’t even the priciest work sold last night at Christie’s. Naturally, that work was by a man: Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose 1982 painting Baby Boom sold for $23.4 million with fees. This means that one Baby Boom is nearly worth two Miss Januarys. (Baby Boom, meanwhile, is worth a fraction of the untitled 1982 Basquiat skull painting that sold in 2017 for $110.5 million. That’s about eight Miss Januarys.)

So far, Dumas’s painting is the most expensive one by a woman, living or dead, sold anywhere at auction this week in New York, whose big three houses—Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips—are all trotting out their glitziest works as part of the annual May marquee auctions. The sales are commonly treated as a barometer for the market, and so it is closely watched by dealers, advisers, collectors, and more.

But the Dumas didn’t even crack the top five priciest works sold this week. All five of those works were by men: Claude Monet, Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Rene Magritte, and Piet Mondrian. As for that last artist, his 1922 painting Composition with Large Red Plane, Bluish Gray, Yellow, Black and Blue sold at Christie’s for $47.6 million, just shy of his auction record.

Perhaps it’s an unfair comparison. Everyone knows that works by dead artists sell for higher sums. But consider, then, the records for other living males represented in that Christie’s sale.

Damien Hirst’s stands at $19.2 million, set in 2007 by a pill cabinet sculpture; Christopher Wool’s at $29.9 million, notched in 2015 by a painting spelling out the word “RIOT”; and Ed Ruscha’s at $68.3 million, minted last year by a painting of a Standard gas station that once belonged to an oil heir. None of these market stars had works that sold for nearly so much last night at Christie’s, which is itself notable—even if Dumas’s benchmark lags behind theirs. Women artists have come a long way at auction, and last night’s Christie’s sale is proof.

Dumas wasn’t the only woman to break her record last night—Simone Leigh did too, with one of her sculptures selling for $5.7 million, and so did Emma McIntyre, whose $201,000 painting was one of the only works not guaranteed to sell. But none of these figures are Mondrian numbers, because no woman artist, living or dead, has ever reached Mondrian numbers at auction. (And Mondrian numbers aren’t even Picasso numbers!) The market still has a lot of work to do.

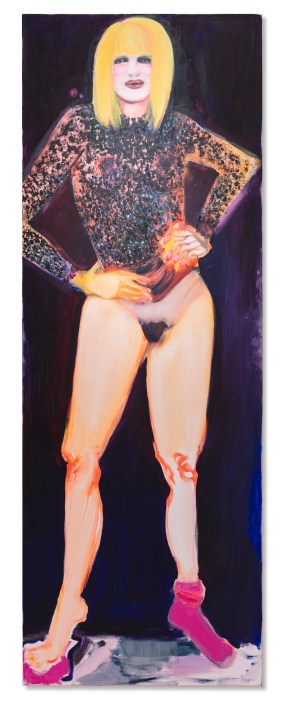

Marlene Dumas, Miss January, 1997.

Christie’s Images Ltd. 2025

At times, it feels like no matter the accolades, the retrospectives, or critical praise they receive, women artists always get the short end of the stick. That’s something you could learn by glancing at Dumas’s CV, which includes some of the very same achievements as some of her male colleagues.

Dumas’s figurative paintings, many of them done in pallid shades of grey, have long been popular on the market, though she has her institutional bona fides too. In 2008, she was the subject of a Museum of Modern Art retrospective, and at the 1995 Venice Biennale, she represented the Netherlands, the country where this South African–born artist is based. She has appeared in four Venice Biennale main exhibitions and two Documentas. In 2022, billionaire art collector François Pinault, a board member at Christie’s until last year, even once turned over one of his Venice museums to Dumas’s work. Yet her art continues to be priced at much lower values than that of many other men.

Values can tell a lot about how marketeers think: the higher the sum, the better the artwork, or so the thinking goes. Miss January is a top-notch Dumas, which may be why the mega-collecting Rubell Family held on to it for about 25 years before selling at Christie’s. Like some of her best works, it raises thorny questions about appropriation and voyeurism.

Dumas based the image on pictures from pornographic magazines, giving it a title that refers to centerfolds. What’s on offer is not exactly sexy, however: the woman wears drag-like makeup, a sheer top, and a single pink sock, hardly the get-up designed to induce racy fantasies. Though she bares her nether regions for all to see, her expression isn’t very inviting either. And she is painted at a grand scale—nine feet tall, to be exact, which means she intimidatingly towers over all who stand before her.

“Why do I use source materials from porno books as models for my figures if it’s not the pornographic that I’m after? Because I can’t see myself when I do the things I do,” Dumas told the MoMA in an audio tour for her 2008 survey. “I don’t know how I look when I look at you.” Miss January is a part of that quest to better understand what it means to act like a female voyeur and gaze back guiltlessly.

The work is as conceptually rich as blue-chip paintings go. But those ideas seem to have steered the piece only so far. The work missed its high estimate of $18 million, and discounting fees, the painting sold for just $11.5 million—which was even beneath its low estimate. Miss January generated just one minute’s worth of bidding. One adviser even called the painting’s sale “unexciting.”

Marlene Dumas.

Getty Images

Prices do not equal art-historical worth, of course, and dollar signs do not confer value upon artworks (for people without a vested interest in the market, anyway). And besides, most of the time, artists don’t even make money when their work is sold at auction. So why care? Because success at auction affords visibility for artists, who are then given further opportunities in museums and galleries. Plus, higher prices on the block mean that dealers can charge more at fairs and galleries, places where artists generally do see money from their sales.

Like it or not, auction prices matter. And as we saw last night, they are part of a larger art ecosystem that continues to hold women back.

But there are signs of hope. A fiber piece by Olga de Amaral, a nonagenarian with a just-opened retrospective at the Institute of Contemporary Art Miami, sold at Phillips on Tuesday for $1.2 million, surpassing her prior record by more than $400,000. That sale also set records for Ilana Savdie, Grace Hartigan, and Kiki Kogelnik. And on Thursday evening, Sotheby’s seems poised to break the record for Laura Owens, the painter responsible for the year’s best New York gallery show so far.

Progress has clearly been made. When Jillian Steinhauer surveyed the most expensive works by women sold at auction for Hyperallergic in 2014, not a single living artist ranked in the top 10, and only one work, a painting by Georgia O’Keeffe, had sold for more than $15 million. That list looks very different today, as Sarah Belmont showed in ARTnews in March.

The problem is that said progress has plodded along at a glacial pace. Dumas’s record re-set the one made by Jenny Saville in 2018, when one of her paintings sold for $12.4 million at Sotheby’s in London. That was seven years ago, which means it took more than half a decade for a work by a living female artist to even cross the $13 million mark. Let’s hope it doesn’t take another seven years for Dumas’s record to fall.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content