Today we’d like to introduce you to Donald Hooker.

Donald, we appreciate you taking the time to share your story with us today. Where does your story begin?

I was orphaned at birth, but I wasn’t orphaned because I was adopted as a baby by a wonderful African American couple, who both have since passed. When my parents divorced at the age of thirteen, that’s when I started getting in trouble with the law because I wanted to have access to things I couldn’t afford and didn’t belong to me, such as boosting the latest designer sweatsuits made popular by such 80s icons as LLCoolJ and Run DMC.

Living in L.A. or the L.A. area, which is the gang capital of the planet, you’re going to have to deal with these people at some point at school. I kicked their ass, but they were like hyenas, they kept coming and kept coming. I grew up playing little league sports, but when my sports buddies didn’t have my back, I did a complete 180°. I rationed to myself, which wasn’t false, “These guys have all the cars, all the money, and all the girls,” so as the ole saying goes, “If you can’t beat them, join them.”

I grew up in the era where “Cripping wasn’t easy, but it sure was fun.” Now, I want to change the mindset of the next generation of would-be thugs and gang bangers that there is another way. You are not going to exorcize the gang culture out of cities such as Chicago and Los Angeles, who have 100-year-old gang sets, but you can educate them on legal entrepreneurship and nonviolent forms of competition.

I belong to one of the oldest Crip gangs in Los Angeles, the World-Famous Raymond Crips, and we were one of the first to bring inner-city sport competition amongst gang sets that we have been at mortal war with. In the October 18th, 2008, edition of the Los Angeles Times, columnist Kurt Streeter reported on our activities in “Peace and football.” [https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2008-oct-18-sp-streeter18-story.html].

In 1997, at the age of 31, I was convicted of a crime I didn’t do. What the State of California had convicted me of was pulling out a knife in downtown Los Angeles’s Skid Row District on a homeless man to prevent him from following me. I received a sentence of 35 years to Life for being my Third Strike. Despite the fact I was not on parole nor probation and hadn’t been in court on a criminal case in over a decade.

I have since been in prison for over a quarter-century with no end in sight. I have not once had a Parole Board Hearing in this quarter-century. Prison has been really ugly, not just for me but for everyone. In the 90s, two federal lawsuits were filed against the California Department of Corrections for constitutionally inept health and mental care.

In the 2000s, these cases were consolidated, and the federal court had concluded the root cause to be medical staff shortage as the result of overcrowding. People were being housed in places that had not been zoned for housing and with triple to quintuple bunk beds.

In the 2010s, a conservative US Supreme Court ordered the State of California to release 30,000 prisoners. You might think, “Why would a conservative US Supreme Court do that?” Well, all you have to do is read the case, Brown v. Plata, 563 U.S. 493 (2011); it’s like reading “Little Shop of Horrors.”

During this same 25-year period, I am living through federal, state, and local budget crises. That meant food, education, and educational trade cutbacks. So, we are pretty much spending our time in prison being unproductive. And while I did participate in the prisoner hunger strikes that led to the abolishment of long-term solitary confinement in the California prison system, those prisoners in solitary confinement had it good compared to the mainline or general population prisoners.

Prisoners in solitary confinement had regular canteen and yard exercise access, but when the general population prisoners would go on lockdown, we did not have access to those amenities. At one stint, as the result of two race riots between African Americans and whites, we were on a two-and-a-half-year lockdown of no exercise yard, canteen, nor packages.

The year 2023 also represents the 10-year anniversary of the largest prisoner hunger strike in US history. 30,000 California prisoners hunger strike to end long-term solitary confinement.

In 2015, the State of California received a grant from Arts-in-Corrections. This grant was sort of a revival to a program that was dismantled as a result of the federal, state, and local budget crises. A beneficiary of that grant was the theatrical troupe The Strindberg Laboratory.

In the late summer of 2015, The Strindberg Laboratory founders Michael Bierman and Meri Pakarinen, who are husband and wife, began to teach theater to a volunteer group of prisoners at the California State Prison, Los Angeles County, B-facility.

California State Prison, Los Angeles County (CSP-LAC), is a relatively new prison in California. It became operational in February of 1993 as the result of a community backlash. California is the third largest state land mass in the Union. It is dominated by a north-and-south configuration rather than east-to-west. 30% of its prisoners are from Los Angeles County in the south, while 70% of its prisons are either in Central or Northern California.

As the late 80s saw anti-crack laws emerge, this caused a backlash by L.A. County residents who demanded to have a prison built in Los Angeles as a result of the prisoner visiting traveling expenses. Any prison built in Los Angeles is going to take on the characteristics of Los Angeles, meaning gangs.

On September 1, 2015, a settlement was reached in a federal class action, Ashker v. Governor of California, that ended long-term solitary confinement in California’s Pelican Bay State Prison. Many of those prisoners were resettled to be housed at CSP – LAC, B facility. The warden at CSP – LAC considered the B-yard to be its hardcore gang yard.

During this time, there was no budget for prisoners to have something to do no meaningful prison reform, so no hope existed of going home. There were drugs, coupled with drug and gang violence. By the time “People Magazine,” came to interview and check out our progress, I was unable to perform for them because my co-star did not show up because he was involuntarily dope sick.

The “People” event would cause the prison administration to shut the theater program down, as they alleged gang signs were being thrown during photo shoots. While the program was able to proceed, the press would be banned.

Much bemoaning came after that edict, but this is where I sprung into action, declaring we would put on a show of such magnitude that the prison administration would be begging for press attention to show us off. This is what happened when we had an encore run in front of politicians, celebrities, activists, and the press.

This led to “BREAK IT TO MAKE IT (BITMI): Busting Barriers for the Incarcerated Project, Los Angeles, California.” A first in the nation prison reentry project that provided two years of free housing from the Los Angeles Mission, two years of free education from the Los Angeles City College, and participation in the jails to jobs program of actual paid theatrical work with The Strindberg Laboratory.

I was told the initial price tag was $600,000, a program that continues to run today. My role in pulling this off cannot be understated; the other prisoner performers demanded my skit be the opening act. My status as an OG commanded and demanded respect. Plus, my overwhelming desire to have my voice be seen and heard over the prison wall. Hollywood actor Joe Manganiello, who witnessed my performance, told me he could not have done that.

In 2017, while listening to Los Angeles Public Radio Station KCRW local news program Press Play, hosted by Madeleine Brand, the topic was reparations for forced sterilization here in California. From my programming notes, forced sterilizations were legal from 1909-1979. 20,000 sterilizations took place between 1919-1953, with Spanish surnames being disproportionately sterilized.

What shocked me was from 2006-2010, 150 women prisoners were forcibly sterilized, and these were just the reported cases. The whole news story was about righting the wrongs of California’s Eugenics program by providing reparations. It was sort of a Public Service Announcement (PSA) that people were actively seeking victims of this practice in order to give them reparations.

However, nowhere in this conversation was there talk of providing reparations to the 150 women prisoners who were forcibly sterilized.

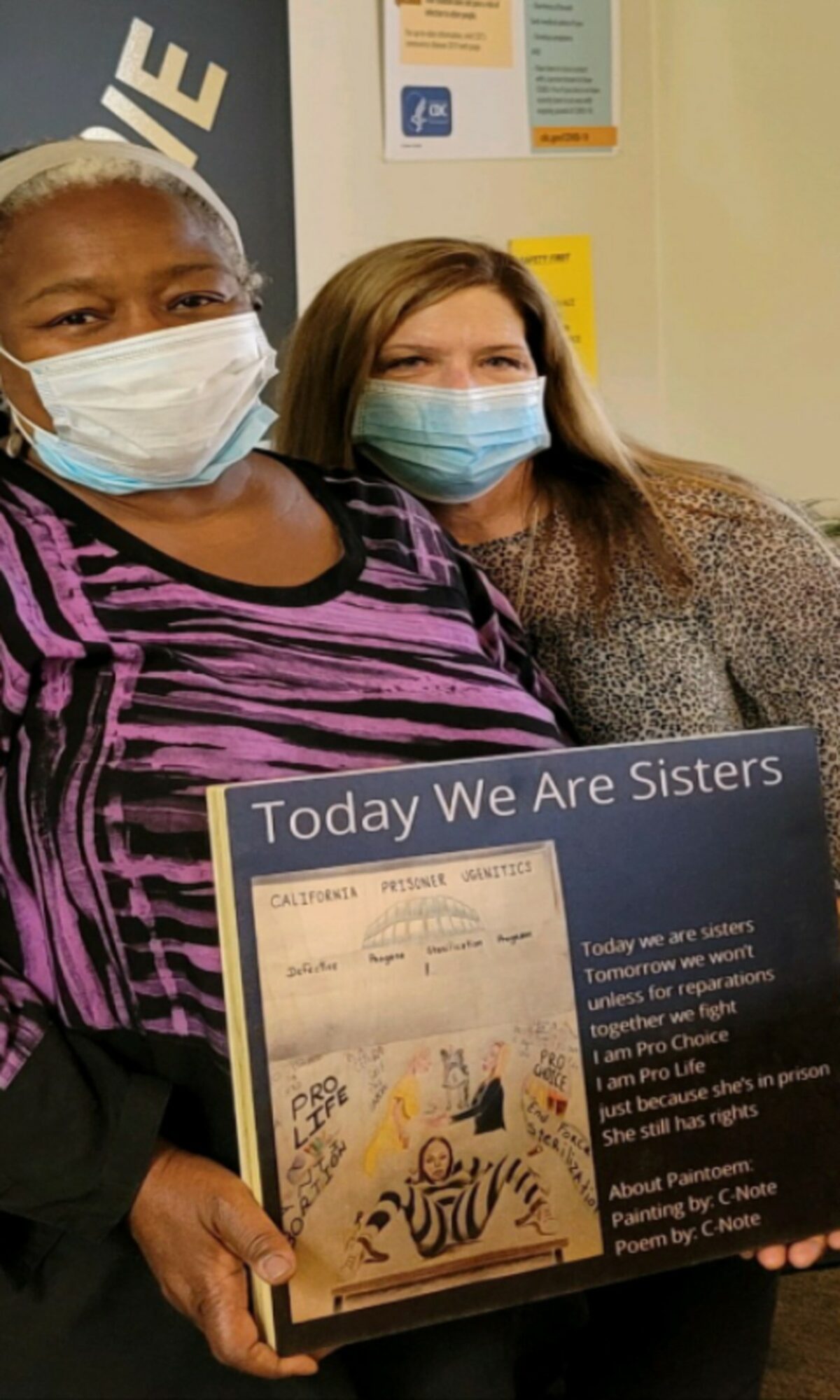

In 2018, I created the Paintoem (painting + poem), “Today We Are Sisters.” The drawing was of a Hispanic female prisoner handcuffed to a gurney with her legs gaped open due to being ankle-cuffed to the gurney. Behind her was a handshake by two white women who represented the protest holding signs of two women groups, Pro-Choice and Pro-Life.

Here is the Today We Are Sisters poem I wrote:

TODAY, WE ARE SISTERS

Today, we are sisters

Tomorrow, we won’t

unless for reparations

together we fight

I am Pro-Choice

I am pro-life

just because she’s in prison

She still has rights

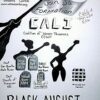

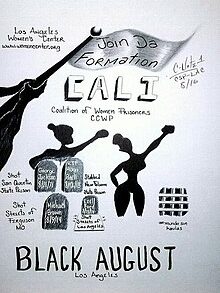

In 2018, I donated the drawing to the California Coalition for Women Prisoners (CCWP). That same year, the CCWP began making an annual trek to the state capital to lobby for these women prisoners to receive reparations.

In 2020, Erika Cohn released her critically acclaimed documentary film, “Belly of the Beast.” It was a film documentation of the California women prisoners who were forcibly sterilized.

February of 2021 saw the release of Free Virtual Art Exhibition (1-Artist; 1-Subject; 21-Works). The virtual exhibition featured 21 of my Works related to incarceration, and concluded with Today We Are Sisters. Shortly after the release of the 21-Works video in 2021, the California legislation put forth a Bill to give California women prisoners who were forcibly sterilized reparations. A $7.5 million reparations Bill was signed into law in July of 2021.

It is very important that this story gets out there because access to the $7.5M sunsets on December 31st, 2023. We are still looking for California women prisoners who were forcibly sterilized to inform them of this California law and their right to have access to this reparation’s money.

These are just two stories. Through Art, I have changed lives, saved lives, raised millions of dollars for rehabilitation and reparations, made history in the fashion world, and my Works have appeared in murals and on billboards.

In 2017, 85-year-old President Emerita and Life Trustee of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and Chairman of its International Council Agnes Gund, sold her 1962 Roy Lichtenstein’s Masterpiece for $165M to hedge fund investor Steven Cohen, placing it amongst the 15 highest works ever sold.

She immediately used $100M to initiate the Art for Justice Fund. A five-year grantmaking fund initiative focused on the racial inequality of mass incarceration. On the Art for Justice website’s About Page, it states, “We make direct grants to artists and advocates focused on safely reducing the prison population, promoting justice reinvestment and creating art that changes the narrative around mass incarceration.”

The Art Newspaper reported in its May 23rd, 2023, edition, “The Art for Justice initiative has awarded $125M over the six years it has been active.” In June of 2023, Art for Justice Fund shut down its doors.

I mentioned this because neither I nor any prisoner I know received any significant amount of these funds, if any, funds at all. I have written about the role of the prisoner’s voice in criminal justice reform since 2016. My 2016, “The Untapped Potential of Prison Art,” has received significant syndication on prison blogs and in the world of academia.

The piece goes into how prisoners receive no money and very little recognition for their yeoman’s work; and my personal experience to get other prisoners to participate in art or to contribute works for criminal justice reform fundraising, I am commonly asked, “Why should I?”

Creating literary and visual works of art for others for free, as promotional works for criminal justice reform, is a form of slavery. Buck Adams of Art for Redemption and Yukari Kane of the Prison Journalism Project they recognize this inherent unfairness in the Rehabilitation Industrial Complex. These two organizations are in the forefront in the movement to pay prisoners for their contributions to the criminal justice reform movement.

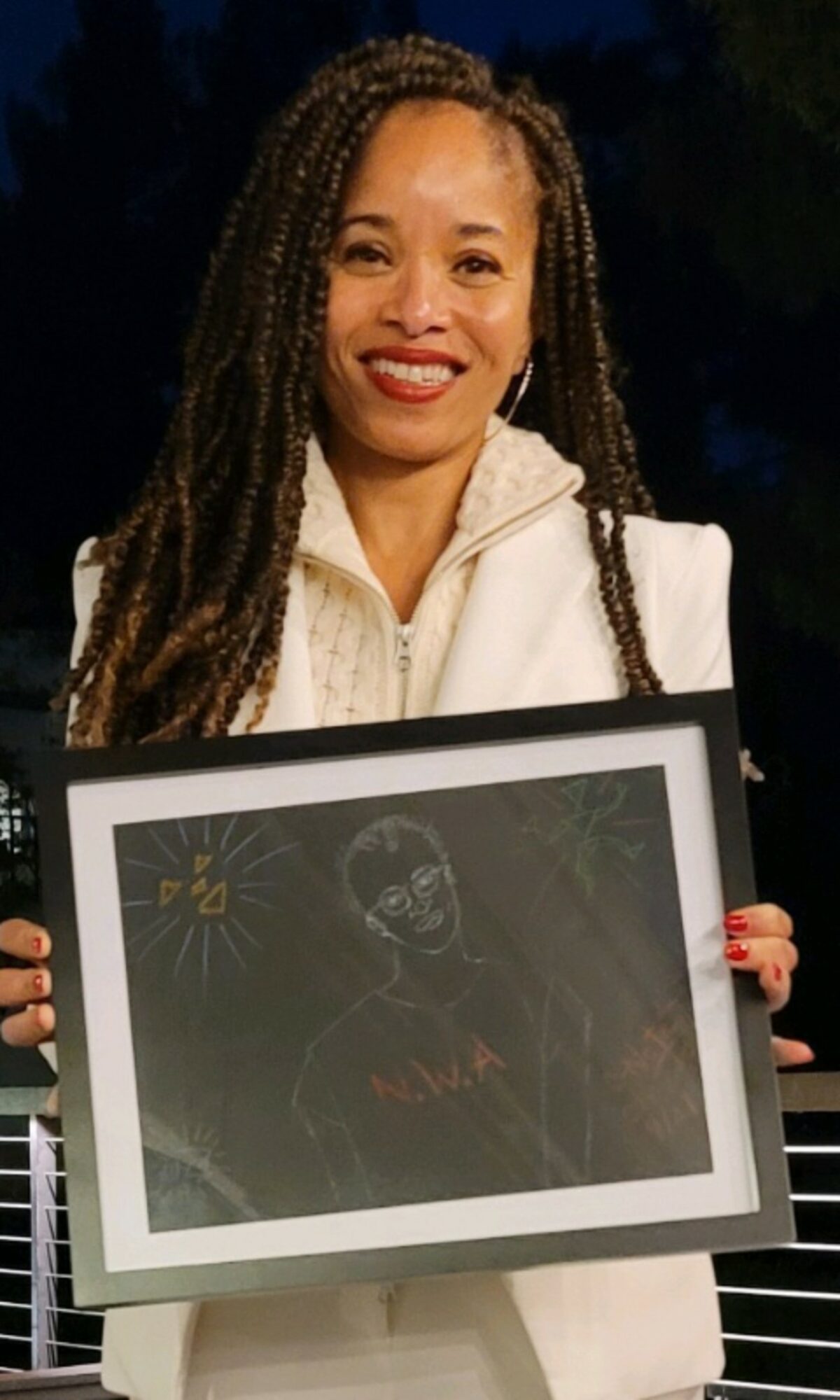

Inaugural James Weldon Johnson Professor at New York University’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, previously Professor of American Studies and Art History at Rutgers University Nicole Fleetwood holding my 2021 drawing on canvas, “C-Note on Haring.”

Dr. Fleetwood’s 2020 book “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” explores the impact of the US prison system on contemporary visual art based on current and formerly incarcerated prison artists. The awards this book has received are too numerous to name. I received an advance copy of the book from Dr. Fleetwood, courtesy of funding from the Art for Justice Fund.

Multidisciplinary artist Samora Pinderhughes, holding up a flier of my “Incarceration Nation,” America’s premier work of art on mass incarceration. In 2023, Pinderhughes’s “Healing Project” received a $1 million grant from the Mellon Foundation. The Healing Project focuses on incarceration and violence.

It is important for the public to understand the inherent societal value in the transformative power of participating in the Arts. There is no greater need to witness the power of this transformation than in the prison setting. Art supplies are not free, and nobody in prison has the money to pay for them. Criminal justice reform organizations are reliant on this Art, also known as the prisoner’s voice.

We must have individuals and organizations of means to give money directly to prisoners as a means of reward and appreciation for their contributions to the Criminal Justice Reform movement.

Would you say it’s been a smooth road, and if not, what are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced along the way?

The most important element to an artist imprisoned or not, is to get their work out and their name associated with that work. Failure to receive recognition can stunt the growth and kill the dreams of any inspiring artist. For the prisoner-artist, this is especially challenging. Their greatest challenge is to get their work over the prison wall.

I was the brainchild of an art exhibit that combined the works of two men’s prison and a women’s prison. The women artists were precluded from having their names associated with their art. These artists were gender discriminated against because of their sex.

Jesse Krimes had federal prison guards sneak his “Dante’s Inferno,” opus Apokaluptein:16389067 (2010–13), out of the prison. For one, the canvas used to create the piece was federal prison bed sheets. That is a crime. It is the destruction of federal property. Also, his opus was so large it could not have been displayed on the walls of his prison cell.

Krimes never saw the finished piece until he was released from prison. It is now a traveling work of art that gets exhibited from museum to museum or gallery. Apokaluptein:16389067 was first exhibited at the Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, in the fall of 2014.

Take prison artist Anna Sorokin, aka Anna Delvey, who achieved notoriety from Netflix’s “Inventing Anna,” she is selling prints of her artwork that states the original work was made with correction facility pens and pencils “on smuggled watercolor paper.”

In the 600 years of Western art, we’ve always heard of secret messages or codes woven into the tapestry of a painting or drawing. That is what the whole book and motion film “The Da Vinci Code” were about. But in Prison art, there are prison authorities along with every kind of law enforcement that scrutinizes every piece of art to see if there are coded messages.

This is something very, very, real, especially those higher profile prisoners who have found themselves doing long-term solitary confinement. The prison authorities and law enforcement want to make sure they are not communicating with their underworld underlings.

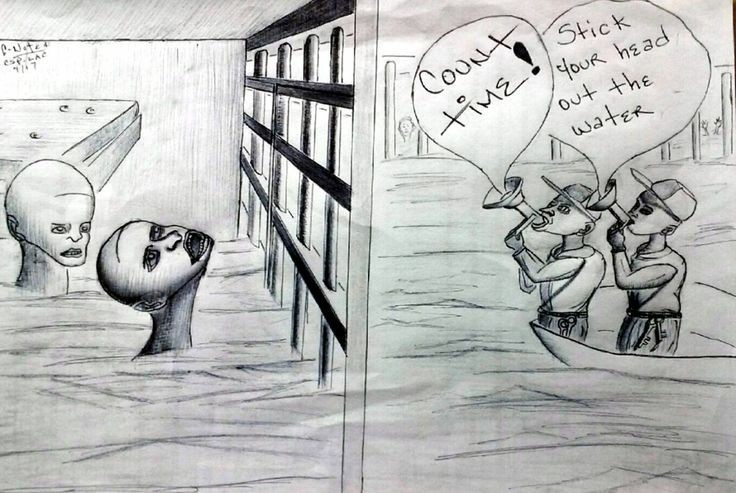

I can’t get up and decide I want to draw or paint a nude because if I do, the artwork will immediately be confiscated, and I will automatically be put in solitary confinement. My 2017 Hurricane Harvey-inspired “During the Flood” should have never been let out of the prison, but because I am not confined at a prison near the Gulf of Mexico, California prison authorities weren’t as bothered by it.

It was my Public Service Announcement artwork and has been used during Category 5 & 4 Hurricanes Dorian (2019) and Ida (2021) to seek prison evacuations by grassroot individuals and organizations. So, my greatest obstacles, not just unique to me but to all Prison artists, are censorship, lack of art supplies, my artwork being seen, but I as the artist, am to remain anonymous, and that 50% of the population is going to speak ill of you as an artist, because of the mere fact of your imprisonment.

Appreciate you sharing that. What else should we know about what you do?

What sets me apart from other Prison artists are my firsts. First Prison artist to have his own Artist’s Billboard exhibition. First Prison artist in the 144-year-old history of the Columbus College of Art & Design (CCAD) to have his artwork on a graduating student’s Fashion line collection. That would be Fashion Designer Makenzie Stiles’s “Mercy” collection.

How my poem and drawing “Journey to Afrofuturism” closed the University of California, Santa Cruz’s virtual event, “Afrofuturism Then and Now.” It was a 2021 – 2022 Academic Year Global discussion and performances on Afrofuturism, and my poem and drawing was recited and exhibited by Hip Hop Congress Board Chairman Rahman Jamaal.

And finally, how I have earned the respect and reputation on both sides of the prison wall as the King of Prison Hip Hop.

What has been the most important lesson you’ve learned along your journey?

To “Stay Thirsty.” I know a lot of people don’t like that term. But record industry people in the Rap world will say, “They are looking for that hunger Rapper.” Or boxing promoters will use that same terminology, wanting a “hungry boxer.”

You can go without food for 30 days but without water for three (days). So that kinda speaks for itself on what kind of level I am on.

Image Credits

Chris Godley

Peter Mertz

Anna D. Smith

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content