Meta’s recent cull of nearly five percent of its workforce has rattled the tech industry on the brink of what CEO Mark Zuckerberg forewarned will be an “intense year.” And while Zuckerberg placed the blame on “low performers,” analysts attribute the layoff spree to a corporate rejiggering within a company that is going all-in on AI.

Casualties of the layoff have turned to online whisper networks such as Blind to air their grievances. Recent posts on the app denigrate the “toxic” culture and grueling demands. Others called out the company’s political about-face.

What’s even more revealing than these anonymous denouncements are ousted employees’ public expressions of strife. Over the last week, terminated workers have turned to X, TikTok, and especially LinkedIn to rebut the low performance narrative. Business Insider described the outcry as a sea change, with “employees sticking up for themselves in public, and calling out their former employer for misrepresenting their work.”

In other words, the demand to project an “ever-employable identity” on social media may be crumbling under the weight of a new phase of personal branding.

The Emergence of “Brand You” in the 2000s

It has been more than a quarter-century since business writer Tom Peters famously exhorted Fast Company readers to frame themselves as the “CEO of Me Inc.” As he wrote in an oft-cited 1997 article, “You’re not defined by your job title and you’re not confined by your job description. Starting today you are a brand.” In the pages that followed, Peters evangelized the tenets of self-marketing: visibility, networking, and self-reinvention.

Since then, the art of strategic impression management has infiltrated nearly all professional sectors—from journalism to medicine, and from art to Airbnb hosting. Anthropologist Ilana Gershon argues that amid an uncertain economic environment, “career counselors, personal branding experts, and self-help publications” all helped to champion a mode of personal branding both flexible and legible. Her title invoked lyrics from Jay-Z’s famous line, “I’m not a businessman. I’m a business, man.”

Of course, the uptick in self-enterprise and status-seeking cannot be understood apart from the astonishing growth of social networking sites. Years before the professionalization of influencers and creators, sites like YouTube and Twitter were billed as audition reels for the new world of work. As The Wall Street Journal headlined in 2013, ‘The The New Résumé: It’s 140 characters.”

As an educator, I have witnessed the cult of self-branding sweep through academia, with professors counseled to “promote or perish”—a play on the “publish or perish” aphorism. Even young school children have been indoctrinated into a culture where they consider their “digital footprints.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, college students poised to enter job market feel these self-branding pressures acutely. I explored the impact of these trends among students in a 2019 article with my collaborator, assistant professor Oliver Ngai Keung Chan. Our research on “the hidden curriculum of surveillance” was inspired, in part, by conversations I had in the classroom. Young people explained they had been socialized to anticipate workplace surveillance—one structured not by current employee monitoring, but instead by the acts of potential—or imagined—surveillance.

More recently, researchers Brady Robards and Darren Graf provided insight into the media narratives that frame public terminations. In a sweeping analysis of news coverage from 2010 through 2020, they chronicled how social media activity gets refracted through “the prism of future employment.”

It’s no small wonder that by the end of the 2010s—an era of hustle culture and multi-hyphenate careers—everything carried a veneer of employability.

A Pandemic-Wrought Workplace

Cute little baby playing on the floor by her working mother. Young mother with a baby and a dog, … [+]

The global COVID-19 pandemic upended many norms of workplace decorum as employers became privy to once-intimate spaces. Suddenly, remote workers questioned whether one’s Zoom background could get them fired. When the boundaries of the workplace are so difficult to discern, so, too are the limits of surveillance. In 2022, a Tesla employee was fired for posting critical reviews—on his own YouTube channel.

But the aftermath of the pandemic also compelled many to question hustle culture. A noteworthy trend was the use of social media not just for work but to also talk about work. Millions took to Reddit’s anti-work community, while others turned to TikTok to publicly chronicle their participation in social media-borne trends like “Quiet Quitting” and “Bare Minimum Mondays.” This act of airing workplace grievances on social media represented a marked departure from the curated, hyper-employable personas of the 2010s. Emboldened by what Zoe Glatt and I described as shifting balance of power between employers and workers, companies began to fear that disgruntled ex-employees could mobilize their own audiences against them.

Layoff Influencers?

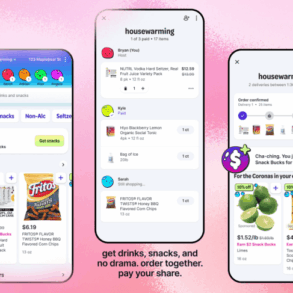

Last year—a time period marked by an estimated 95,000 layoffs in the tech sector, saw the emergence of a trend bearing the unlikely imprint of the creator economy: layoff influencers. Months after a tech worker found viral fame for broadcasting her firing, reports began to emerge of terminated workers and other work-related “vulnerability porn.” Nothing how the stigma of getting fired had been supplanted by influencer logics, a Bloomberg report noted, “Losing Your Job Used to Be Shameful, Now It’s an Identity.”

Whether Meta’s latest round of layoffs bears new workplace ambassadors remains to be seen. But it is noteworthy that workers are publicly airing their grievances and contesting the ever-employable front. At least, for now.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content