Editor’s Note: The following story contains discussions of sexual assault and physical abuse. If you or someone you know is struggling, call 1-800-656-HOPE (4673) or visit online.rainn.org.

Nearly 40% of Mexican women and girls have experienced intimate partner violence, according to a 2021 national survey of over 3,500 participants ages 15 and up, with more than a fifth reporting incidents within the last 12 months. Bookending Women’s History Month with a crucial call to end this cycle, a pop-up exhibition of Mexican artist and activist Elina Chauvet’s work in New York City will probe gender-based violence, domestic abuse, and femicides as a national phenomenon and a universally felt crisis. Curated by Galería 1204 Director Lorena Ramos and MAD54 founder Aida Valdez, Corazón al Hilo will run from March 26–29 at at 102 Franklin Street in Tribeca.

Chauvet made waves internationally in 2009 with “Zapatos Rojos (Red Shoes),” a poignant public protest installation that arranged hundreds of donated pairs of shoes in formation, each standing in for a woman who was killed or disappeared in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico — including Chauvet’s own sister, who was killed by her husband at age 32.

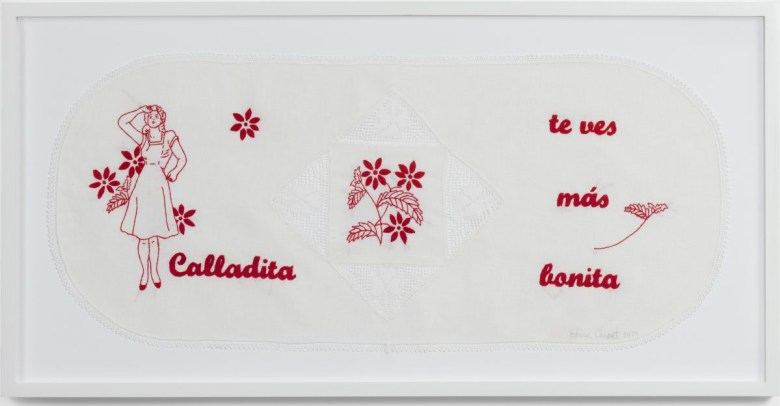

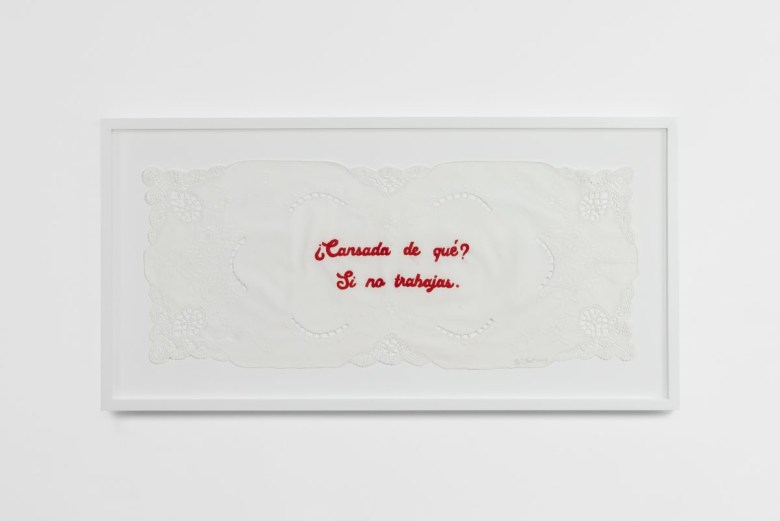

In a new body of work on view this week, Chauvet stitches a line between delicacy and brutality, approaching the seeds of spousal abuse and subjugation that germinate into violence and often murder. The embroidery series, titled Heridas Domesticas (2023–), pierces dainty white doily place settings with blood-red threads spelling out insults in Spanish: “estúpida” (“stupid”), “tonta” (“dumb” or “idiot”), and “inútil” (“useless”). The words are accompanied by phrases like “Calladita te ves más bonita” (“you look prettier when you keep quiet”) and “Solo sirves para servir” (“you are only good for serving.”)

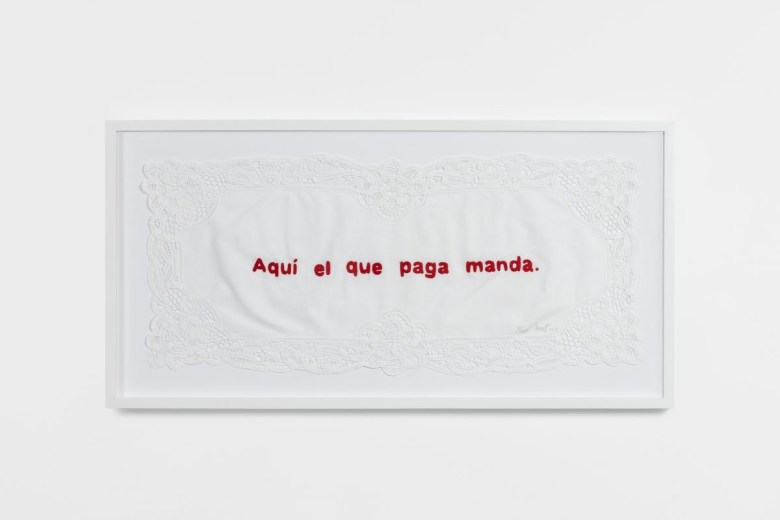

One doily reads “Aquí el que paga manda,” which translates to “Here, the one who pays, rules,” underscoring the gender disparity of unpaid domestic labor and craftwork versus employment as well as the precariousness of financial dependence in abusive situations.

“There are certain patterns that repeat in verbal domestic violence, which many women recognize because we have either witnessed or experienced them,” Chauvet explained in an email to Hyperallergic. “It’s a common yet violent language that is rarely discussed, and it is usually directed at women. What is not seen or named does not exist.”

She deployed such aesthetic gentleness with aggressive text in an effort to “provoke reflection and stir the conscience of both genders,” noting that both men and women have been receptive to the series so far.

In addition to Heridas Domesticas, Chauvet’s exhibition will also include a session of her ongoing performance “Confianza” (2013–), in which the artist quietly hand-embroiders text onto a wedding dress. “Confianza” was born from the performance of late Italian feminist artist Pippa Bacca, who set out with her friend and fellow artist Silvia Moro on an international hitchhiking tour in 2008 from Italy to Jerusalem in white wedding dresses to promote world peace and a “marriage between different peoples and nations.” Bacca and Moro split up in near Istanbul with the intention of finding each other again in Beirut, but Bacca disappeared and was later found dead after being raped and strangled by a man she accepted a ride from in Gebze, Turkey.

Chauvet embroiders Bacca’s story and her understanding of trust onto the dress in public spaces internationally. In a video shared on social media, she recalled being ejected from the grounds outside the United Nations building in New York for embroidering “Confianza” onsite.

“Sitting outside the UN building to embroider was symbolically important to me,” she told Hyperallergic. “I didn’t expect to be threatened with arrest if I refused to leave, even after explaining the purpose of my action to the officer. That was the moment I realized the symbolic and political power of a needle and thread — how an act as simple as embroidery can become a form of resistance, protest, and struggle.”

Chauvet mentioned that she was detained by Vatican police while performing in St. Peter’s Square, where she dedicated the piece to mothers whose daughters were victims of femicide in Mexico.

“Despite multicultural differences, there are common languages and patterns that transcend ethnic, cultural, social, and economic distinctions,” she continued. “Women have been subjected to the same patriarchal and misogynistic systems in similar ways worldwide. That is why I choose to address these issues through art using a universal language — one that everyone can understand.”

Chauvet will host a “Confianza” workshop for the duration of the pop-up exhibition’s closing day, inviting New Yorkers to reflect on trust and ongoing violence against women.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content