My second morning in Robion, a village in southern France famous for its summertime melon festivals, I attacked the cantaloupe I had bought at the market with a knife, picked at it for breakfast, and set off. Oppède-le-Vieux was about eight kilometers from where I was staying on a research grant, and I was going there because I wanted to see the world of a character I was trying to invent. The historical existence of Consuelo St. Exupery, a Salvadoran artist who moved in Surrealist circles, had inspired me to insert a fictional character with the same first name into a novel I was just beginning to write, a book that eventually became The Volcano Daughters.

Little had been written about the historical Consuelo, and even less had been written about her art. Consuelo was better remembered as the tempestuous wife of Antoine St. Exupery, and the muse for his petulant rose character in The Little Prince. Records of her childhood in El Salvador were scant; she had spent most of her adult life in France, which is why I was in Robion.

They remade the rule-bound magic of Surrealism by living by their own fantastic rituals, reclaiming their power, and remaking the world with their creations.

After a long separation from her husband, Consuelo was left alone in Paris during the German occupation. She fled south, first to Marseille, and then to Oppède-le-Vieux, to a place she called “The Kingdom of Rocks,” an artist colony and refuge during the war.

Consuelo had written two memoirs of her time in the place, where she elides tricky questions about whether or not she slept with some of the hot artists she met there, with a good deal of wistful musing about the mistral and humble-braggadocio. I knew that what had already been written about Consuelo, including what she had written about herself, would not breathe sufficient life into my character.

Consuelo was not in the small museum of Surrealism that I had visited the day before, but, because of the slight way she showed up in other records–as a wife, a muse, an unknowable exotic, with brief mention of her artistic aspiration but not of her art—I didn’t expect her to be. Other, more famous Surrealist women in that circle, a group that includes Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varos, Adrienne Fidelin, Leonor Fini, Lee Miller, made unremarkable appearances in the museum. I imagined that some of them might have been her friends, though I have no way of verifying this theory. Like the others, Consuelo partied and posed for Man Ray, but unlike those Surrealist women who came to be reconsidered at the end of the 20th century, their work properly celebrated and studied, Consuelo, for whatever reason–Talent? Artistic output? The confinement of her marriage?—stayed buried. She never made her name by her art.

It was 2012 when I visited Oppède, and I did not yet have a smartphone, but I took a mediocre camera and a notebook, in which I had transcribed the walking directions from Mapquest on my laptop–out of the village of Robion and through the Luberon mountain range, to Oppède-le-Vieux. After an hour or so of walking, I determined that I was lost. I found fields of lavender and stalls selling soap, but the mountains were nowhere to be seen. I had walked in the wrong direction, back towards the train station in Cavaillon, where I had arrived a couple of nights before. I entered a small market and found more sliced melons, some cheese, and water. I regrouped in the hot, dusty air, eating my melon and consulting a pair of satin-eyed horses who proffered their long noses over a fence, before I set off again.

“They were our muses, not artists,” said Roland Penrose to feminist scholar Whitney Chadwick in the 1980s, on the topic of Surrealist women. Leonora Carrington, great painter of sentient horses, then in her late 60s and living in Mexico City, told Chadwick later, “Bullshit. I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse. I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist.”

The misogyny and objectification the Surrealist women experienced in their time was not just characteristic of the ordinary patriarchy around them, but central to the ideals of femininity laid out in Andre Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto: “Women are the most marvelous and disturbing problem in all the world.” The most useful women were muses, idealized as children, “femme enfants.” Women were not human. They lacked insight, a drive to create their own art. Later, when I read translations of the Popol Vuh, the Mesoamerican Book of the Woven Mat, I was struck by this mythology’s concept of humans at the heart of its creation story: insight, the ability to create, desire. These were the qualities that made humans real.

When I finally arrived in Oppède-le-Vieux I was out of breath. The path had wound itself in tightening circles as the elevation peaked, and the light was swelling over the soft mountains. Pink roses spilled over a crumbling wall and the village lay before me. I climbed the wide stones, inspecting each small structure that had once been a dwelling, and I sat in a pew of the church and took some notes, attempting to record everything that I could see: mountains, sunset, roses, shadows, dust puffing up from the rocks.

Unsurprisingly, many Surrealist women grew tired of being pliant muses, and broke with the male-dominated collectives to create their own bonds of artistic companionship. They remade the rule-bound magic of Surrealism by living by their own fantastic rituals, reclaiming their power, and remaking the world with their creations. The label of “Surrealist” had become too loaded and proprietary, too much of a loathsome brand, though the women embraced their own mortal magic. When Breton applied the term Surrealist to Frida Kahlo, perhaps simply because she was a Latin American female artist familiar with death and the divine, she rejected the label outright.

A connection to the divine, an interest in prophecy and dreams–these could be threads traced around Europe and Latin America, artists and heads of state. The Spiritualist and occult practices adopted by Surrealists in the service of art-making were connected to similar Spiritualist and occultist practices embraced by the Theosophist dictator of El Salvador at the time (from whom the fictional Consuelo, and her fictional younger sister Graciela flee in my novel.) While amongst the artists the supernatural informed automatic writing, channeled paintings, and later, sanctified the women’s own collectives, for the General, seances and potions dyed with food coloring provided self-absolution for his 1932 massacre of 30,000 mostly Black and Indigenous people, La Matanza. “It is a greater crime to kill an ant than a man, for a man can reincarnate, and an ant cannot,” he is remembered for saying. Color theories were neatly applied to the caste system of skintone introduced by Spanish colonists, dovetailing with the General’s eugenicist impulses.

I never found any record of the real Consuelo acknowledging La Matanza, or of any experience or feeling toward the dictator’s ideas and regime. Many Salvadorans at the time were no different. As she is written in history, Consuelo’s life begins in early adulthood, outside of the country. But I wondered about another version of her, someone who had witnessed both of these surreal worlds, who that person might be. In the novel I eventually wrote, Consuelo, and her younger sister Graciela, who has no historic corollary, are both tied to this brutal history.

I experienced something akin to heatstroke as I began walking back to Robion. A kind man in his eighties met me on my walk. His name was Domenique and he offered me cherries from his orchard, some water, and showed me his paintings–dark landscapes in oil. He drove me back to Robion in his tiny car, the sky graying around us. The next morning, he called outside my window, inviting me to Mass and then a coffee. It would be over a decade before I would finish my book.

I recognized in their dreams, dismissals, and rebellions, in their refusals to live inside other people’s projections, and in their fierce desire for artistic community, a bit of myself.

About four years after I walked through the Luberon to find the kingdom of rocks, I had a baby at home and an incomplete manuscript, and I encountered Whitney Chadwick’s book Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement, for the second time. I’d borrowed Chadwick’s book from the library at the university where I taught but had to return it and wasn’t able to check it out again, or find it in print anywhere. Then it was there, sitting on top of a free pile in the graduate lounge that I noticed on my hasty path from my office to the restroom to clean my breast pump, an embarrassingly mortal prop in academia. My son was about six months old, and I was teaching classes at night while my husband worked during the day, to avoid paying for childcare. I was so deliriously exhausted that I regularly experienced aural hallucinations. I heard them whooshing now, and it seemed the fluorescent lights in the graduate lounge were winking in time with my mind, rejoicing. Free pile, huh? I guess Surrealist women weren’t cool/serious anymore. Had they ever been cool/serious? It didn’t matter. This was a gift. I stuffed the book into my breast pump bag.

Chadwick doesn’t write about the historical Consuelo, but she writes about the other women who made art about their bodies, their desires, and their losses. Reading their stories I recognized in their dreams, dismissals, and rebellions, in their refusals to live inside other people’s projections, and in their fierce desire for artistic community, a bit of myself as I wrote this book, navigating history and my responsibility to it, resenting expectations of this yet unfinished thing, interrogating my own creative impulses.

The recursive, timewarped process of writing a novel reminds me now of the looped sequence of creation in the Popol Vuh, the mythical epic’s surreal movement between gathering the materials to make human beings, and then three-quarters of the way into the text—after Blood Woman multiplies maíz (the key ingredient for infusing human beings with insight, desire, and creativity), after her journey through the Middle World, after a wild series of tales involving owls and false hearts—time abruptly resets, and the narrators insist upon an eternal present.

At some point in my process, Consuelo separated entirely from the incomplete histories that had been written about her, and became her own, merely la tocaya, or the namesake, of the historical one. My Consuelo is petulant only sometimes, an artist, and an older sister. My Consuelo freezes in Paris and wraps herself up in woolen armor, paints pupils on her eyelids, and wears a spider floating in resin around her neck.

I remember myself, alone in my twenties, searching the series of caves and keystone arches leftover from the Romans, by the grace of my travel grant. Amongst the pale dusty ancient stones I glimpsed a small face. There was no marker, nothing to draw attention to this one stone unlike all the others, save for the roughly carved face itself. When I asked Domenique about the face, he knew nothing about it. I mistrusted my vision, but later my mediocre camera told me otherwise.

A gift to me from the kingdom of rocks, I gave the face in the ruins, and its act of creation, to Consuelo. This is when she became real to me, alive both in the history and in the fiction, though it was years and drafts later when I wrote about Consuelo sculpting the face. I don’t know who carved the face or why, but for my purposes, Consuelo had sculpted the face of her long-estranged sister Graciela into the stone, in order to make a lasting work of art in a ruin, in order to remember someone that, to her, felt forgotten by the rest of the world.

__________________________________

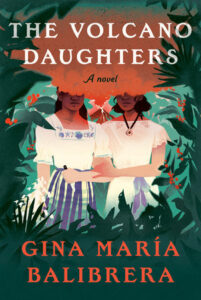

The Volcano Daughters by Gina María Balibrera is available from Pantheon Books, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.