Moto Hagio is a unique figure in the male-dominated world of Japanese manga, breaking down barriers and revolutionising the comic book genre since the 1970s. France honoured her with an award and exhibition at the Angoulême International Comics Festival in January.

Issued on:

4 min

Advertising

At 74, Moto Hagio is still at the top of her game. Much to the delight of French fans, the Angoulême International Comics Festival invited her to give a masterclass alongside fellow Japanese authors Hiroaki Samura and Shinichi Sakamoto.

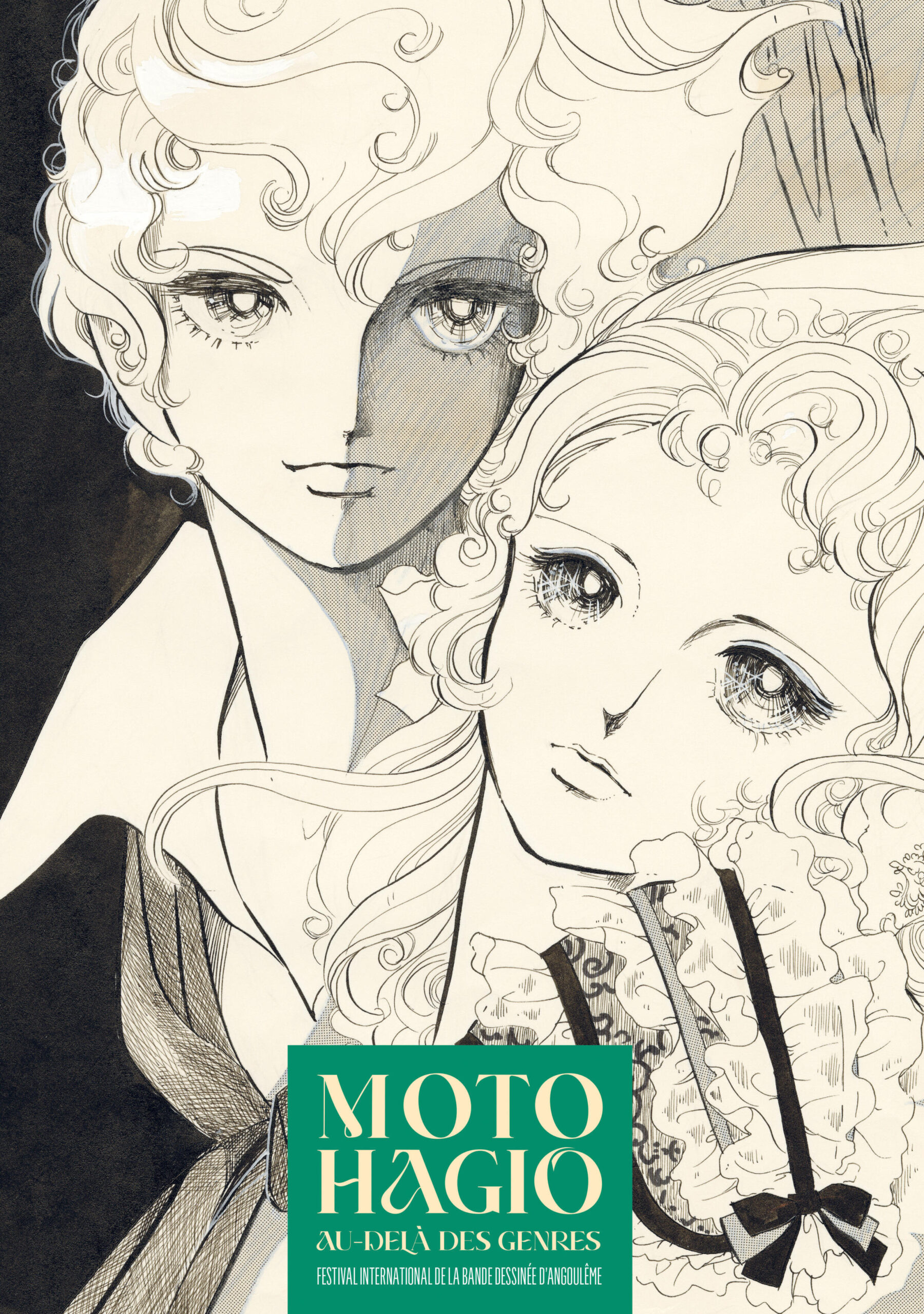

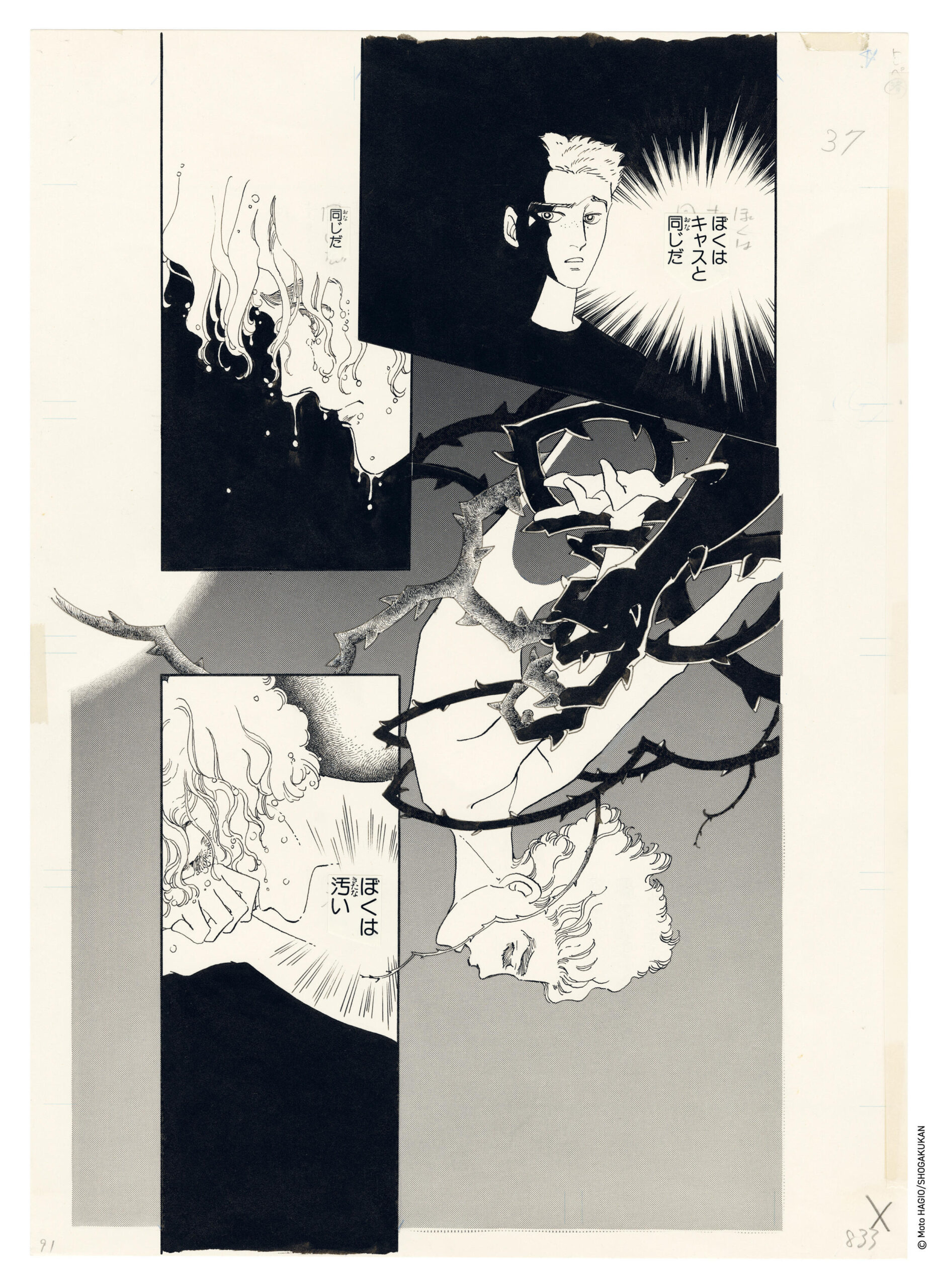

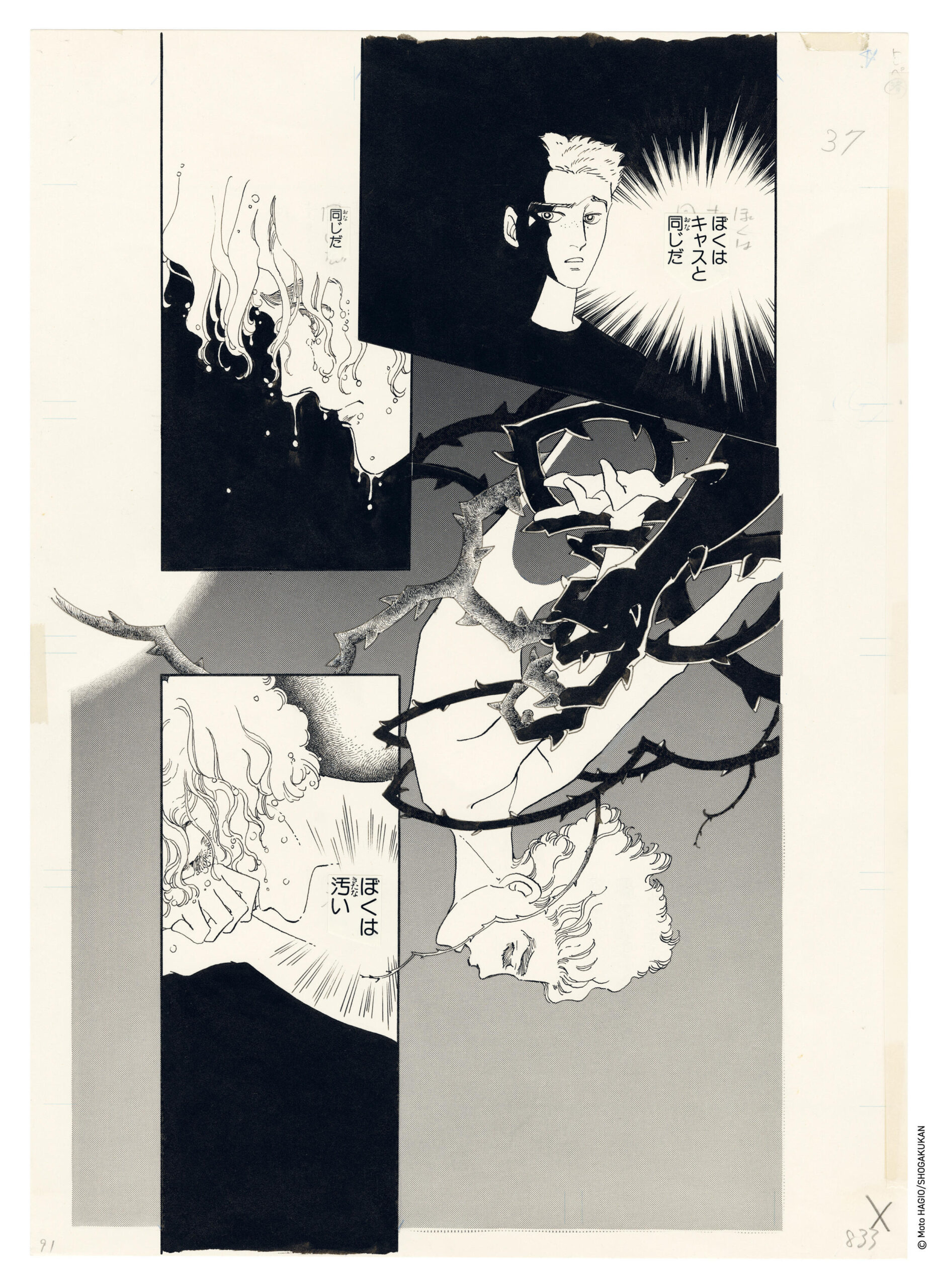

Not only was she handed the Fauve d’honneur – a lifetime award acknowledging her contribution to the comics industry over the last 50 years – but a large selection of her work was also chosen for the exhibition “Beyond Genres” at the Angoulême Museum. It is on display until 17 March.

Exhibition co-curator Xavier Guilbert is thrilled that French audiences have had a chance to encounter a pioneer of the industry and get to know her extensive work better.

“We are lucky enough to have a lot of her work being translated into French, but they only represent a little part of her entire production,” Guilbert told RFI during the festival.

Manga offers audiences a way of “travelling”, he said.

Manga integral part of culture

Guilbert, who lived in Japan, calls manga “integral” to Japanese culture. It also allows space for “criticism directed at society or exploring its fantasies or aspirations”.

“We thought it was a good opportunity to cast a light on part of the history of manga that is usually put aside,” he told RFI, suggesting that male artists tend to pull more focus than their female counterparts.

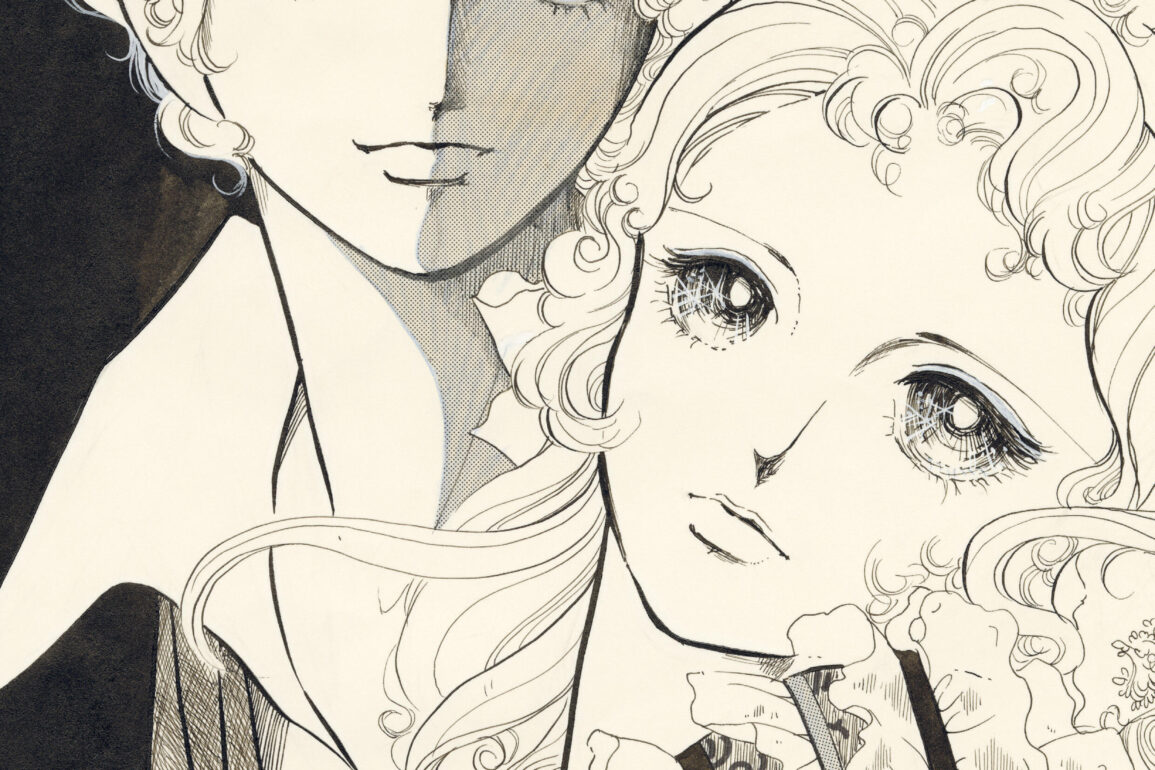

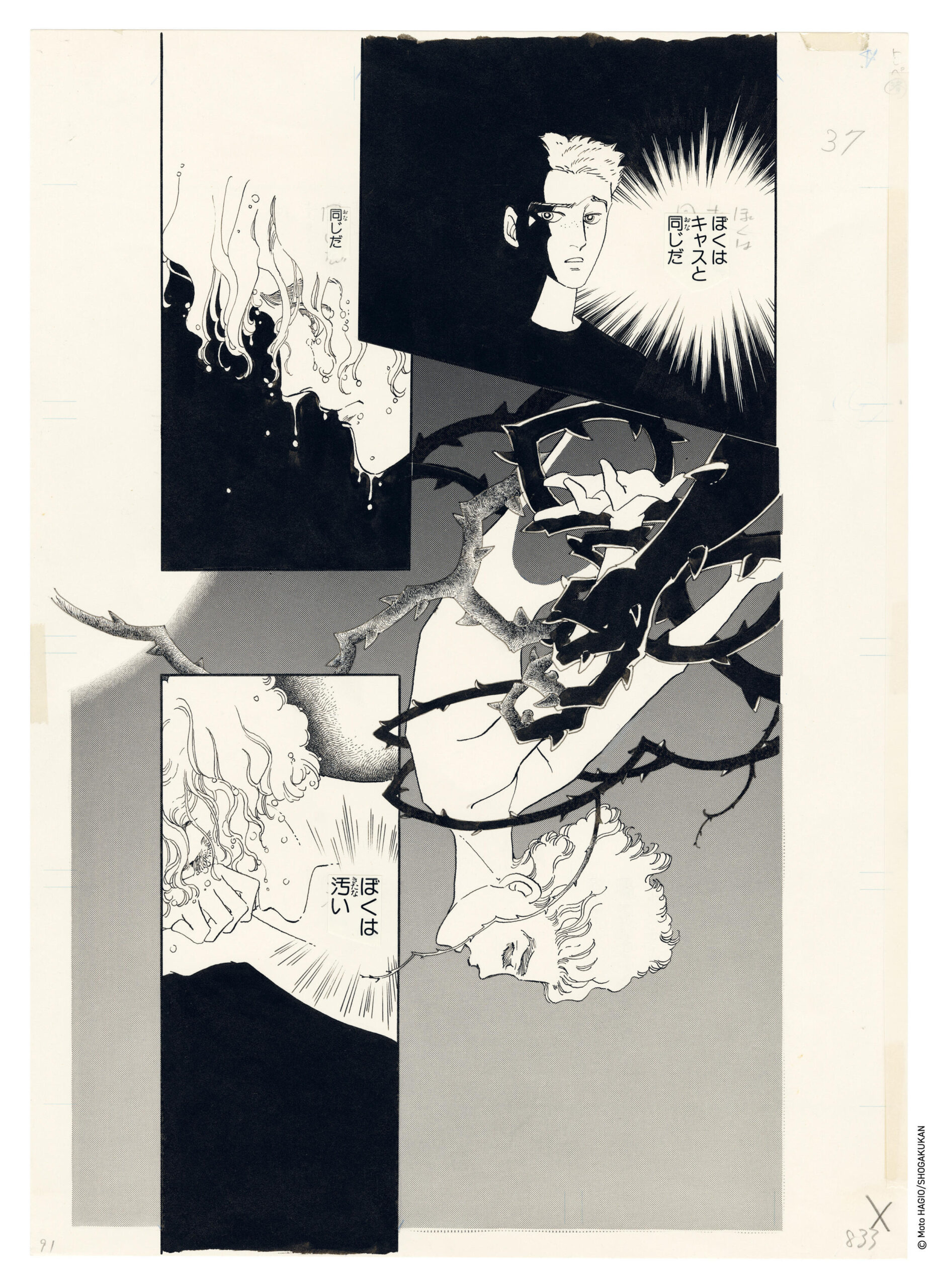

He points to the variety of Hagio’s framed drawings around the exhibition space. Hagio’s finely sketched, expressive faces peer out from the crowded panels. They are mostly in black and white with translated captions appearing alongside the original in Japanese.

“The objective was to bear witness, to showcase all the different directions and different themes that she has tackled over 50 years of her career,” Guilbert explains.

Having grown up as an avid manga reader, and fan of famous mangaka Osamu Tezuka, Hagio launched her career in 1969 with contributions to the girls’ magazine Nakayoshi.

Her breakthrough came in 1971 when, after joining Shôjo Comic magazine, she was able to publish unconventional works that other publishers had rejected.

Creative wave

Hagio belonged to a women’s collective, known as the Year 24 Group, who strived to bring about different creative styles.

With members like Keiko Takemiya, they are credited with making shojo (“girls”) manga central to production in the 1980s and attracting a male readership to the category for the first time.

Hagio distinguished herself with The November Gymnasium in 1971, a short tale inspired by German writer Hermann Hesse. In 1974, she turned it into a longer series known as The Heart of Thomas.

The long saga recounts the lives of adolescents at a German boarding school, the death by suicide of a fellow student, sexual awakenings, friendships, identity and family secrets.

These works, known as yaoi, featuring love stories between male characters, propelled Hagio into the international limelight.

In 1972, her vampire series The Poe Clan brought commercial success that led to greater creative control over her future publications.

Then, in 1975, she published They Were Eleven, an impressive work of science fiction, then a genre little explored by female writers.

Overflowing imagination

Hagio is one of few authors of her generation to blur the lines between fantasy and personal life, turning her strained family relationships, particularly with her mother, into inspiration.

Although she has an overflowing imagination, she never hesitated to adapt works by other Japanese writers, and was inspired by American authors Ray Bradbury and Ursula Le Guin, as well as European literature.

Hagio’s stories have been adapted into movies, TV shows, and plays. She has received many awards including Japan’s Person of Cultural Meritin 2019.

“I always try to take on board the reaction of the readers and the editors but in the end I just do things my way – I don’t care about what they say,” Hagio once said.

Guilbert and fellow curator Leopold Dahan featured the quote in the exhibition catalogue. Guilbert says it gets to the heart of why he admires Hagio’s work so much.

“That’s really what defines her work,” he says.

“She was set on doing things her way and she never faltered from doing that. And when you look at her entire work, there’s a consistency. It’s very coherent in the themes that she approaches and the kind of message she has.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content