On the plane back from Miami, I add up expenses versus income from this year’s Untitled Art Fair. It is our third year here, and our first bust. As a small Midwestern gallery, two major art fairs a year — Untitled in Miami and the Outsider Art Fair in New York — can generate a quarter of our annual income. Even more importantly, they help us develop a national collector base for regional artists. There is no other way to survive.

It is expensive to participate in more selective and carefully curated international fairs, such as Untitled. Our three-walled, 14 x 14-foot space cost $17,400. Housing for the staff, transportation, food, and additional framing rounded out the total to about $30,000.

For the first time, we lost money. It hurt.

After three days of almost no sales, I began talking to other galleries. Most reported an equally slack climate. The art market has been soft for two years. No one really knows why — maybe the volatile stock market, the toll of wars, the ravages of natural disasters, the erosion of the middle class, escalating prices of art, rising inflation. A recent Artnews article reported — off the record — that many galleries suffered drops in revenue of more than 50% from the year prior, and even auction houses like Sotheby’s and Christie’s reported declines of 30%. “The art market is clearly in crisis,” it adds.

At dinner, a gallery director friend from Los Angeles said that the past two years have been so bad that she cannot absorb additional loss. I asked her how another smaller New York gallery did. Not good.

Uncertainty is the defining feature of the art world. When things sell, it feels invigorating, even addicting. When they don’t, spirits plunge. When sales are robust, it confirms that the craziness of producing and selling art is actually a viable activity, that artists can earn a living by making things, that the infrastructure of it all, from artists to dealers, to curators, institutions, collectors, and writers, is not so fraught, that it is a glorious swirl of love and conviction. Those directly involved in this profession cling to the knowledge that art reveals the best of humanity; that to look at a painting or a sculpture is to see an earnest reflection of our best qualities: open-mindedness, rigor, and exploration.

The world needs art. But the heightened commerciality of major art fairs can also strip its integrity. When sales falter, the art world begins to feel untenable and its wares begin to look suspect, like shiny and pointless amusements for the wealthy.

At Untitled, 171 galleries from around the world display carefully chosen objects under an elaborately constructed tent-like building on the beach. White walls and bright lights support other tools of seduction such as monumental scale, gleaming surfaces, and evidence of intense labor and skill in photorealist paintings or intricate objects.

During the fair, when booth traffic lulls, I scan the crowd, but my observations quickly become blurred in their repetition. The best distraction from the tension of wondering if and when some members of the crowd will wander into my booth and find something to their taste and budget, I discover, is to stare at the work in it. I try to keep my focus by remembering that most of these works originated in the quiet of an artist’s studio, where struggle, contemplation, and commitment stewed with pride, skill, and intelligence, where artists wrestled privately with self-doubt and other demons. Finding new details seems to anchor my nervy discomfort, as if I am re-grounding myself amid hometown friends.

But even then, the voice of uncertainty lingers: “Why am I doing this?” Few professions rest on such shaky ground. It takes a toll. And then, in a revelatory flash, I remember why I stay in this profession: The unpredictability of the business also means that anything might be possible at any time. Uncertainties also hold promise. Nothing feels routine or totally controllable, meaning that each new project, catalog essay, art fair, or exhibition brings fresh thoughts, discoveries, and the grace of sharing this bizarre, insular world with a public.

At these fairs, art passes from the hands of the artists to those of dealers before it, hopefully, reaches the homes of collectors. Gallerists must reconstitute the human depth of these objects by providing information, context, and practiced rhetoric. We are thanked multiple times each day for taking the time to chat. Visitors feel honored by the direct contact.

That connection does not always yield a financial return. At our gallery, the same artist who nearly sold out the booth during the private preview day last year sold very few works this year. For the first three days of the art fair, we had more inquiries about the handmade designer furniture in our booth than the work on the walls.

Everyone said that Saturday and Sunday would be better at the fair. Saturday passed, with one small sale. Sunday, the final day, slid quietly through its five-hour, last-gasp promise. A couple comes in the booth and admires a six-by-four-foot canvas by a young midwestern artist. As we did with hundreds of people before them, we chat, exchanging observations about the work. The painting of three giant women armed with swords in a Medieval fantasy land reminds them of their own three daughters, and they buy it. It is our first five-figure sale of the fair. It will not get us to the break-even point, but it lessens the loss.

After six days of business, on Sunday at 5pm, a shockingly fast flurry of deconstruction consumes the cavernous space. Dealers who just five minutes ago looked stylish and erudite are on their hands and knees, wielding tape and bubble wrap, and negotiating large objects into custom-built boxes where they will rest on journeys across seas or county lines. The zip of packing tape and whoosh of plastic wrap washes through the halls, a quietly urgent and embedded part of the profession. White-gloved handlers meet exhausted dealers who all hunker down to wrap and pack. It is a strange life, I think, both rarefied and gritty, intellectual and dutiful. At a small gallery such as ours, the owner and one staff member curate, hang, spackle, sweep, ship, prepare marketing materials, update the website, draft press releases and newsletters, and manage client relations. Most small galleries skid by on marginal revenue. In the Midwest, most gallerists have other sources of income.

From energy-infused Instagram posts, I can tell that that gallery dealer friend from Los Angeles, who experienced equally slow first days, rebounded by the finish. I am happy for her.

Before heading to the airport, I go to the Perez Museum to meet an old friend. Surprisingly, as we step into the museum, I freeze. A full-on wave of anxiety shoots through my fatigue, and I am completely repelled by the countless objects before me. I tell my friend, Natanya, an art historian, that I will not be able to engage fully. She kindly says that it is OK, we will just stroll and chat. She pauses in front of a Carmen Herrera painting, “Alba” (2014). I would so like to hear her talk about this wunderkind Cuban-born artist, who died in 2022 at age 106. Herrera’s strong, simple geometric abstraction of green rectangles abutting pale raw canvas at acute angles feels life-infused. But no, I couldn’t do it. Pangs of sadness puncture me when I think about the fact that it took Herrera until age 89 to sell her first painting, when the tide of the market turned in her direction. The art world reflects the injustices of the larger world, just skillfully masked in connoisseurial jingoism.

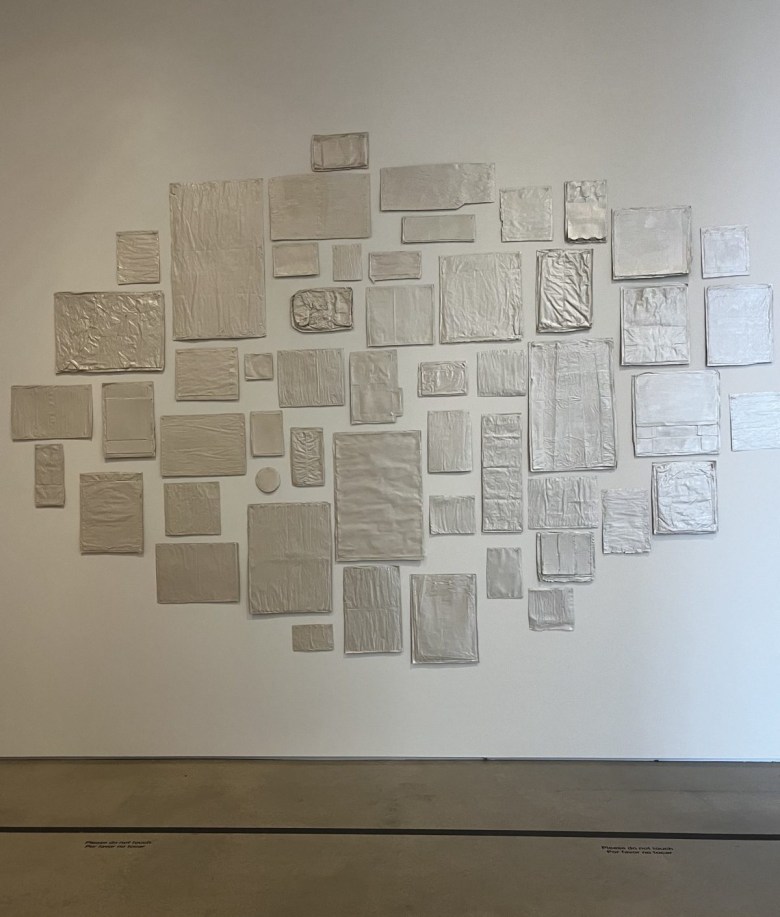

I shuffle alongside my friend. Every object makes me cower. We drift into a new room. One wall holds an array of rectangular shapes covered in silver. I don’t recognize the artist, but I pause. The shapes are actually mailers and found packaging. The humble veneered materials feel like an antidote to the thousands of over-intentional objects colored with disappointment that have populated my week. I’m not sure why I find such pleasure in this. Maybe it is the layering of waste and wonder (discarded mailers, silver sheen), or perhaps this piece by Mexico City-based artist Abraham Cruzvillegas makes the portent of transformation tactile, while also holding firm to bits of the world or one’s path through it. At the museum, in front of his piece, I feel my spirit re-enter my body, as if I had lost myself, then tenderly found a bit of it again, in this forest called the art world.

Soon, all the work we didn’t sell will be in a van driven by my son and gallery manager, careening across the country with its nose aimed at Wisconsin. They will drive straight through, 26 hours. Somewhere in Georgia, there will be fog. By Tennessee, it will rain.

Back home in the gallery, I get a text. It is an inquiry about our largest, most important work at the fair. Currently, it is still under consideration by this client. I wait, fingers crossed.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content