For years, Native art in Colorado has been pushed into the corners: a special section of the museum, a mural people pass on the way to baggage claim, or a textbook inset wedged between Manifest Destiny and the transcontinental railroad.

Artists whose ancestors were here long before Colorado had a name have had to go out of their way just to avoid being forced to the margins. But in Niwot this weekend, 12 Indigenous creatives from around the region are showcasing their work, front and center.

The Niwot Native Art Market is back for round two and returns 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Sunday at Niwot Hall, 195 2nd Ave., Niwot. The event is free to attend, and runs on an artist-first model: there are no booth fees, thanks to community support, and artists keep 100 percent of their earnings.

The inaugural market, held in March, was, by all accounts, a hit. According to organizer and Boulder-based artist Tom Myer, the event drew a large and steady stream of visitors all day long.

“The market … was a doorbuster the entire day,” he said. “I didn’t count exactly, but I would say probably 500-600 people came through the door in the four or five hours we were there. I mean, we were never alone for a minute.”

The inaugural event, which featured eight artists was, to Myer’s knowledge, the first Native art market in Niwot history.

“Which is pretty incredible, and also kind of surreal, because the town is, after all, named after Chief Left Hand,” he said, of the Southern Arapaho chief.

The unexpected turnout, while exciting, also highlighted a larger truth.

“Here in Colorado, we have 48 historical tribes,” Myer said. “The Denver March Powwow is the second largest powwow in the world. It draws people from across the country, from Mexico and Canada, and when you go, it’s wall-to-wall Native. But if you go to the Boulder Farmers Market or the one in Longmont, you see zero Native artists.”

That gap between cultural visibility at large-scale Native events and near-total absence in mainstream local spaces is exactly what Myer set out to address.

“There’s a number of reasons for this,” he said. “Costs are super high. If you were to investigate getting a table as a vendor at the Boulder Farmers Market, or other art shows, they’re paying several hundred dollars just to have a table. That’s a huge risk, right? Are you going to sell several hundred dollars’ worth of art? We don’t always know.”

Myer said to take a look at the local museums — except for the Denver Art Museum, he said, which houses “one of the greatest collections of Indigenous art in the world.”

“Typically, you walk into a smaller museum or gallery and you see zero Native art,” he said, “or it’s always a special exhibition. They’ll have what we call ‘regular artists,’ and then they have Native arts, which is rather ironic.”

Myer, who has long been involved in the Native arts community, said the goal is simple: get Native artists in front of buyers.

“That’s the big barrier,” he said. “People love Native art, not just the traditional stuff, like pottery and beadwork, but also contemporary art. But the problem is, it’s hard to get in front of people if they don’t know you even exist.”

That is exactly why the Niwot Native Art Market does not charge artists booth fees. Removing barriers, Myer said, starts with making space.

This weekend’s event includes artists working in digital media, comic books, printmaking, and abstract painting, representing nations including Apache, Lakota, Navajo, Cheyenne and Native Hawaiian. The artists have traveled from across Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona and beyond.

Myer’s work will be featured at the market, including a striking piece titled “Encroachment,” which shows an American flag advancing across a river of fire toward a row of tipis under a massive yellow sun. The land behind the flag bleeds into turbulent red, while the sky is a storm of layered blues.

“I was kind of in a trance when I made it,” Myer said. “But people really connected to it, and it got a super strong reaction from Native and non-Native folks.”

His work often draws from Native mythology, history and symbolism, rendered in a style he describes as semi-abstract and energetic. Some pieces center on figures like Thunderbirds or mythic buffalo, others on portraits of Indigenous people or stylized animals.

“You have to kind of explode what you think Native art is,” he said. “It’s not just paintings of chiefs cross-legged in front of a tipi. Native art can be anything.”

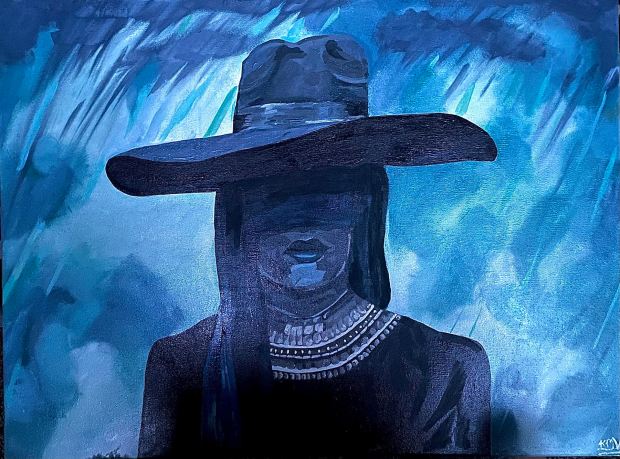

Another artist breaking the mold is Keelie Mijares-Vallie, a Lakota Sioux and Turtle Mountain Chippewa painter whose work leans abstract and contemporary — two words not always associated with how people picture “Native art.”

Her pieces often blend vivid colors with layered textures, creating what she describes as “a mix of color and part black and white,” though for this weekend’s market, she’s bringing her more colorful, nature-inspired works. Some feel soft and comforting, others are sharper, more confrontational. All of them resist easy categorization.

“Not all artistry is the same, and it has changed throughout the years,” Mijares-Vallie said. “But I appreciate that my heritage can support me as an artist in this new age.”

While she doesn’t expect every viewer to interpret her pieces the same way, she hopes they feel something personal.

“Some of my pieces are more cheerful and have a comfort type of vibe,” Mijares-Vallie said. “Others are empowering and resonate differently. I hope people experience their own connection.”

For artist Salix Renan, connection is also at the forefront of their artistic practice — with the land, with culture, and with others. A citizen of the Muscogee Nation with Cherokee ancestry, Renan first learned to weave in 2017 while living in Oklahoma. Since then, they’ve turned the practice into both a teaching tool and a form of personal grounding.

Now based in Denver, Renan uses basket weaving to help others reconnect with their hands, their histories, and the natural world.

At this weekend’s market, they will lead a hands-on demonstration, inviting attendees to sit down, slow down and complete a small basket of their own. Teaching, they said, is as much about sharing knowledge as it is about creating space for people to surprise themselves.

“The hardest part of weaving a basket is starting one. That first hour is full of doubt,” Renan said. “Then they get an inch in, and they’re like, ‘Oh. This looks like a basket. Am I a basket weaving master?’”

Renan’s current pieces use rattan, a flexible vine from the palm family that is widely available and affordable. While it’s not a traditional Cherokee or Muscogee material, it closely resembles buckbrush root runners and honeysuckle vine, both of which were historically used in Southeastern basketry.

River cane, once the primary material for Cherokee weavers before their forced removal from Colorado to Oklahoma, has become harder to access over time. Today, using rattan is not just a matter of convenience, Renan said, but a reflection of adaptation and survival.

“The story of the materials reflects the history of land loss, adaptation and resilience,” they said. “Now, in 2025, I work with rattan because that’s what I have access to.”

By choosing rattan, Renan makes it possible to teach without charging high prices and ensures their work remains accessible. The material allows them to honor the tradition of Cherokee basketry as both a cultural practice and a form of commerce.

“Historically, Cherokee people have done basket weaving as a form of commerce,” they said. “That’s always been part of the practice. It feels good to carry that forward.”

Whether through bold color palettes, layered symbolism, or quiet acts of craft and care, each artist in Sunday’s market brings something distinct. Together, they offer art and perspective, and in a town named after Chief Niwot, both are overdue and necessary.

“It’s important to give space to Native artists in ways that aren’t confined to heritage month or history museums,” Myer said. “This is about honoring our presence now, and making sure people see us — not just our past.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content