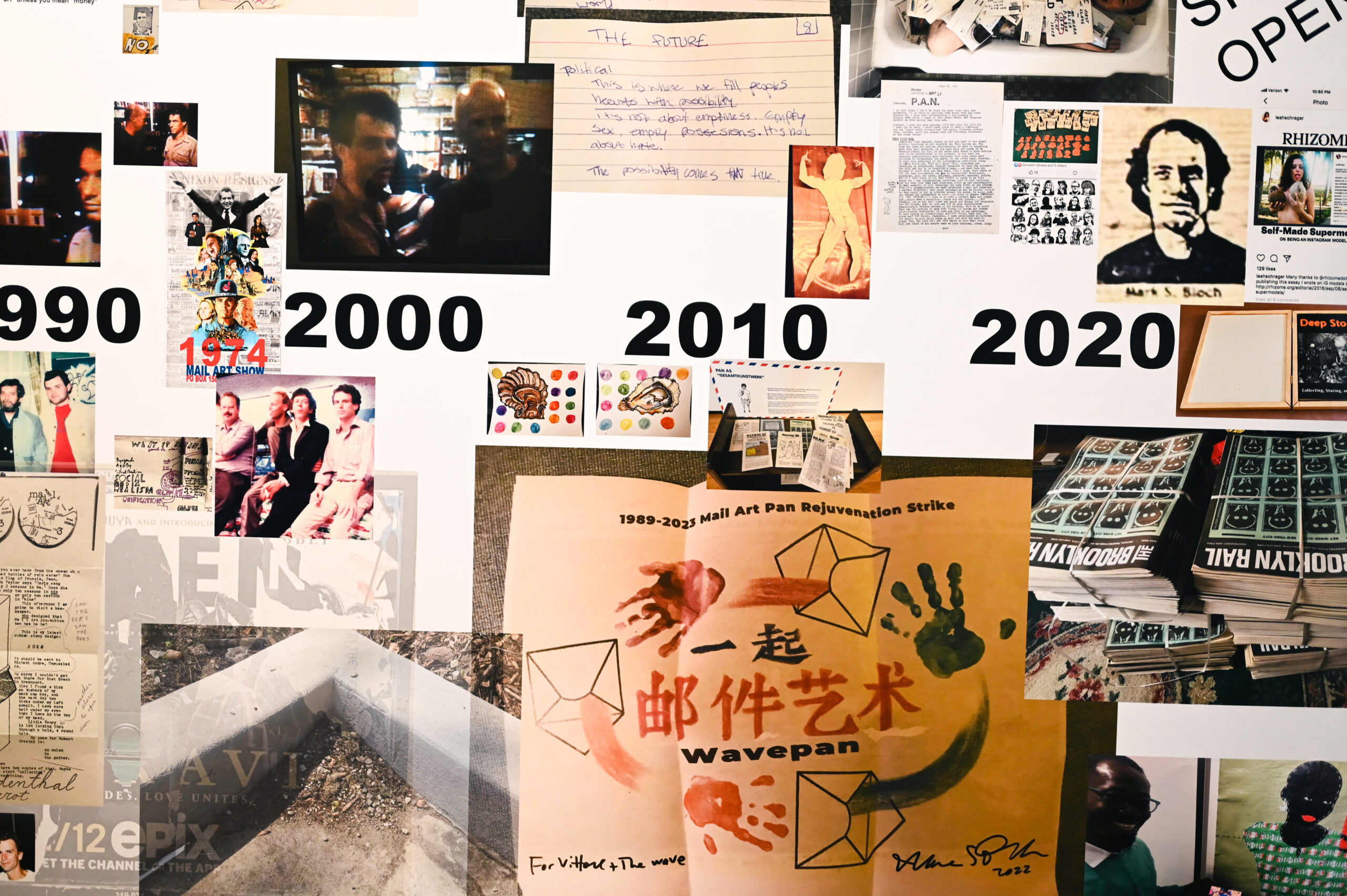

Panmodern! The Mark Bloch / Postal Art Network Archive

The Fales Library and Special Collections at the NYU Bobst Library

September 17–December 13, 2024

New York

Mail Art jelled into a more or less codified form in the sixties, around the same time that the Fluxus Art Movement fomented. Fluxus artists emphasized the performative event over the marketable product, and interdisciplinary activity over traditional art genres. Yet perhaps the earliest example of Mail Art tactics emerged from Surrealism in the form of the Exquisite Corpse game in which participants would pass on their drawings to one another to be morphed by chance towards unexpected results. Mail Art expanded upon this basic idea, disbursing amongst an international cast of players a wide-ranging play of word games, concrete poetry, activist (and absurdist) politics, visual punning, and alter egos. In this sense it predicted the more ludic aspects of chance meeting by all of the above in the current social media landscape.

Mark Bloch, an artist, writer, and longtime practitioner of Mail Art, has carefully archived the scope of his engagement to amass a representative cross-section of each of the form’s successive phases and technical elaborations in this tightly co-curated (with Marvin Taylor and Nicholas Martin) and usefully annotated survey. His initiation into alternate art forms was prompted by a visit from Joan Jonas in 1977 to his Kent State alma mater. Jonas exemplified for Bloch an open-ended approach to artmaking and its traditional categorical distinctions. He’d go on to strike up a correspondence with Ray Johnson, arguably the most infamous Mail Art artist of them all, who inspired Bloch to delve into the roiling and unpredictable waters of the international mail art community. As a result, Bloch embarked on his Postal Art Network in 1978, soon shortening its name to the acronym PAN, cleverly establishing an attitude of impromptus associated with the Greek god Pan, appropriate to the playful ethos and aleatory aspect of Mail Art in general. Bloch subsequently engaged in the elastic back and forth of a worldwide community of like-minded practitioners of what might also be called postal performance art, the “props” of which he carefully archived (between 1978-2013). These were then collected by the Fales Library of New York University which occasioned the current exhibition, Panmodern! The Mark Bloch Postal Art Network Archive.

A variety of Mail Art manifestations are laid out in vitrines that track the movement’s aesthetic development and technical evolution. One wall text makes the cogent point that such a practice took for granted the relative magnanimity of the postal service to deliver the mail no matter what it contained or in what form it took. This “postal-historical a priori” as the Fluxus artist George Maciunas would term it, represented a de facto relationship irrevocably connecting improvisatory, often Dada-inflected gestures of mail artists to dependable structures of social order and egalitarian interchange, therefore simultaneously flying both above and below the “radar” of cultural conservation. Maciunas famously encouraged sending bricks through the mail as a way of testing the ongoing function of such an inherently conservative, but democratically dependable, communicative apparatus of the state. Different artifacts displayed in this vitrine exemplify such systematic tests, like a gym sock affixed with postage and a Styrofoam postcard pierced with pins, together with, incredibly, an apology note from a postal worker regarding its damage by the postal system’s sorting machinery. Other vitrines document Neo-Dada permutations, which instrumentalized mail art’s worldwide influence, including the Neoist movement that took inspiration from the Letterist and Situationist art movements of the late forties through the early seventies. Neoist practitioners like Canadian artist Monty Cantsin and British artist Stewart Home dovetailed their anarchic projects, such as “The Festival of Plagiarism” (1989) and “Art Strike” (1993) with cadres of mail art artists as a means of networking and economical distribution.

Navigating the different tributaries that feed into the larger Mail Art flow can be confusing, as its egalitarian nature doesn’t throw up distinct social or political partitions. Yet there is a distinct undercurrent that feeds it all, an art genealogy of Dada to Surrealism to Situationism to Fluxus that intermingles with a DIY and punk sensibility. This exhibition goes a considerable way towards parsing different manifestations into discrete periods, including how the growth of communication technologies has augmented and altered delivery and response. With the arrival of the internet and its more general usage in the mid-nineties, options arose for artists to connect more quickly and efficiently to worldwide networks. The early days of the internet saw Mail Art avatars like Bloch taking to Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) to extend their reach, thus the collation of stacks of paper matter gave way to virtually stored communiques. What was gained in immediate, intimate accessibility with BBS (one could chat directly with John Cage or Bill Gates, for instance) gave way to the current social media industrial complex that now seems to choreograph one’s every waking moment in a vast conformist ballet.

In a conversation I had with Bloch while researching this review, he said that there wasn’t really a distinct falling off of Mail Artists with the rise of internet intersubjectivity but rather that during its whole history there have been people jumping on and off all along. His belief is that there is a renewed interest in the tactile qualities and out-of-bounds aesthetics of mail art missives that appeal to a younger generation of artists turned off by the often repressive influence of the social media they’ve grown up with. The temporal disconnect (and attendant conformity) that virtual communication can engender is well put by Thomas Pynchon in his 1965 novel The Crying of Lot 49: “Everybody who says the same words is the same person if the spectra are the same only, they happen differently in time, you dig? But the time is arbitrary. You pick your zero point anywhere you want, that way you can shuffle each person’s timeline sideways till they all coincide.” Pynchon’s narrative famously hinged on a conspiracy theory of dynastic control of the mail via the Thurn und Taxis nobility, a prescient paranoia considering the current rise of new media oligarchs and their digital gate-keeping and tribute taking.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content