The podcast episode accompanying this article answers several traffic-related questions, including one about how city traffic lights are timed and another about why construction on I-90/I-94 happens the way it does. Click “listen” at the top of this page to hear the full story.

High school math teacher Connor Cameron cannot be late for work. “If I show up at 8:05 there are 30 students who are unsupervised,” Cameron said, “and I cannot afford to do that.”

Cameron teaches on Chicago’s Southwest Side but lives in the northern suburbs. “My journey starts on the Edens,” he said, “Then I’m on the Kennedy, the Dan Ryan for a split second, and then the Stevenson” before eventually making it to residential streets.

According to the 2020 Census, about 59% of city residents and more than 86% of people living in the surrounding suburbs commute by car. Like hundreds of thousands of his fellow drivers, Cameron relies on the morning traffic reports for his lengthy commute to work. It got him wondering what goes into making those reports he hears on WBEZ or WBBM. Where does the raw data come from? How do they calculate those time estimates for different roadways?

The traffic reports air daily with such frequency that they can feel commonplace. But behind the scenes, it’s chaotic putting together a single report. Often one traffic producer sifts through dozens of sources of information to create that 30-second report drivers hear on the radio.

We spoke with one longtime traffic reporter and producer to learn the ins and outs of putting a report together. He told us how he juggles listening to police scanners and checking live video feeds before sitting down to record a report that will be heard by thousands of drivers — and about some of the most harrowing moments on the job.

Chances are if you’ve heard a Chicago-area traffic report on the radio in the past twenty years, Mike Pries helped put it together.

He works for Total Traffic and Weather Network, which manages a traffic database used by nearly every local news outlet.

He works from a studio downtown, a small room outfitted with a few computer monitors, a mixing console with microphone and several police scanners blaring at once. At any given moment during his shift, Pries is listening to more than 20 police scanner dispatchers, pulling updates from countless state and county agency websites and fielding notifications from databases like Pulse Point, an app that tells him where first responders and other emergency services are headed. He’s also checking live video feeds of some roadways and monitoring hundreds of traffic-related Twitter accounts.

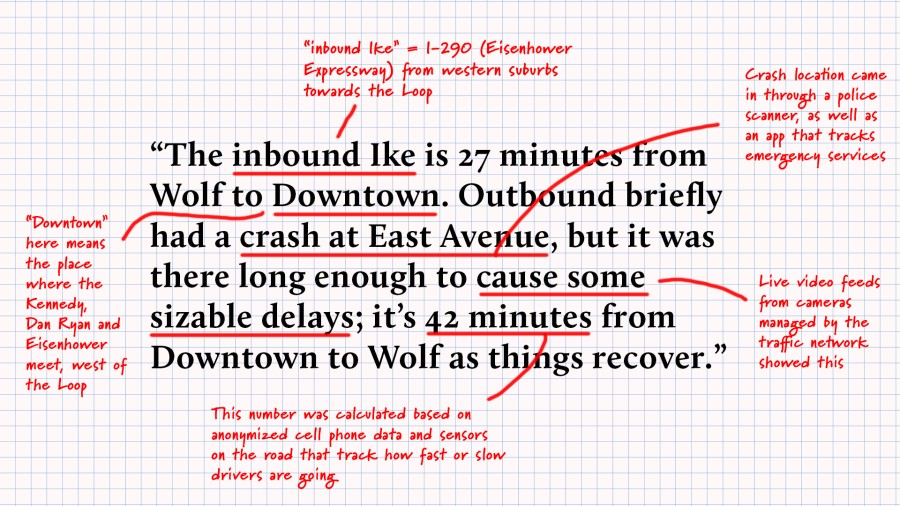

Pries’ day-to-day consists of tracking and translating all this data and turning it into traffic reports that he’ll record or broadcast. For shorter reports, Pries emphasizes only major incidents or slowdowns, while some of his lengthier broadcasts provide a thorough overview of Chicago-area traffic.

He also estimates travel times for navigating expressways and major avenues. Those times are in part based on passive cell phone data that tracks the average speed of drivers moving down an expressway, but also on Pries’ own analysis of how a certain incident may cause a backup for surrounding roads.

“It’s not just, ‘How many minutes is it going to take you to get from O’Hare to downtown?’” Pries said. “If you have a crash outbound on the Dan Ryan at 18th, you know that pretty soon that’s going to start backing up the Kennedy going into downtown. And if it stays there long enough it’s going to affect the Eisenhower, too.”

In addition to his own reports, Pries and his team also maintain a database called Traffic Net, where they input entries for things like crashes, construction and other incidents. Those entries then get pushed out to Total Traffic and Weather’s various clients, which include radio and TV stations that may have their own reporters or anchors who read the broadcast scripts.

It’s this ability to quickly process information that makes Pries’ reports valuable and thorough. In fact, some GPS systems use data from Total Traffic and Weather Network to generate their own travel time estimates. “You need someone to pull it all together, get it all in one place, so that it can go out to everyone as a cohesive product,” Pries explained.

Traffic reporting is generally a fast-paced and stressful job, but there are times when it is harrowing, especially when winter weather hits. Pries recalled a blizzard in 2011 that caused total pandemonium on the roads.

Pries said they were receiving reports of buses jackknifing and cars getting stranded and buried under snow on Lake Shore Drive. “And people are on [Lake Shore Drive], they’re calling us. And they’re saying there’s no one out here,” Pries remembered. “And, you know, we’re not emergency responders, we’re not trained in that capacity. But people are calling us because it was chaos out there.” Pries did his best to reassure those callers, providing updates as he heard dispatchers being sent to their location.

A big part of the job, Pries said, is navigating the gravity of a serious incident while maintaining the fast-paced turn of the next report. However, despite it being hectic, Pries loves what he does. “Even when it’s incredibly stressful,” Pries said, “I can’t say that it feels much like work. It’s always interesting and keeps me on my toes.”

Andrew Meriwether is a reporter and producer based in Chicago. Keep up with his work at andrewmeriwether.com

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content