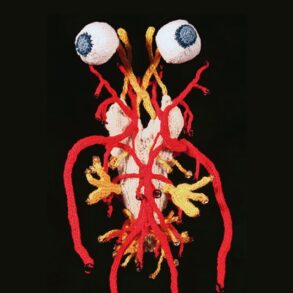

Her large paintings on wooden panels, which she calls ‘scrap paintings’ (in reference to scrapbooking, an activity that she considers a bit ‘trivial and poorly considered’), are replete with mysterious inscriptions, which she describes as ‘a form of galactic, talismanic writing.’ Profoundly influenced by the work of British author and critic Ekow Eshun and Pan-Africanist Nioussérê Kalala Omotunde, Choisne is also driven by a desire for reparation and healing: ‘I connect with an energy, I channel messages from other worlds to create new temporal lines of healing and make our planet healthier.’ The artist also tries to ‘create a sort of transgenerational and fictional family.’ She glues, assembles, and superimposes photographs of Black families that she often finds at flea markets or even created from scratch by AI. To these, she adds ‘rubbish’ found in the street, such as bits of paper or stickers, but also locks of hair. ‘I often use fake hair, like the kind used in Afro extensions. I like this trivial aspect, something that isn’t considered noble. And then, with hair, there’s the notion of roots….’

Haitian on her father’s side, and Breton on her mother’s, Choisne is marked by these two cultures that are ‘complete opposites in the way they perceive the world – one through intuition and the invisible, and the other through mathematical and physical rationalisation,’ she explains. ‘Instead of fighting them, I embraced these contradictions. It took me a long time to understand that there was no need to choose.’

As the storm finally breaks outside, and torrential rain beats down on the city, she adds: ‘I play with colonial and decolonial history, I represent Black bodies, the bodies of trans or non-binary people. As a Black woman, I don’t believe I always have a space where I can feel secure, so I create my own spaces, my “safe spaces.”’