Coinciding with the new blockbuster show, Gauguin’s World: Tōna Iho, Tōna Ao, at the National Gallery of Australia, Nicholas Thomas’s latest book offers a provocative perspective on two of Paul Gauguin’s most abiding themes — women and Polynesia.

By far the most famous of the Frenchman’s paintings feature the women and landscapes he encountered in the French-occupied Tahitian and Marquesan Islands between 1891 and 1903. “Over the last forty years,” Thomas writes in his preface to Gauguin and Polynesia, “I have walked around Gauguin exhibitions, fascinated but also frustrated.” During those decades, Australian-born Thomas has worked as an anthropologist, art historian and curator of Pacific people and artefacts. His frustration has been driven by the lack of connection between Gauguin’s representation and public knowledge of the Pacific, a lack that his new book aims to rectify.

Whether or not Thomas would feel frustrated by the current show at the NGA is unclear, but he would surely be annoyed by some of the commentary circulating in the Australian media. It’s not that he’s unsympathetic to the ubiquitous discussion of Gauguin’s cancellable personality — his history of sexism, colonialism and paedophilia are worth debating in an era that is scrambling to figure out who deserves public recognition, and in what ways. Rather, Thomas is frustrated by how these debates rehearse damaging assumptions about Pacific women and Pacific cultural survival. In their rush to condemn Gauguin, commentators conjure up powerless girls and a destroyed society. Gauguin “took child brides” and “used them as models,” the critics write, creating a “mythical land” over a “spoilt Polynesia.”

Thomas’s book asks two questions. What does it say about the women of Polynesia if we foreground the idea of Gauguin as an indefatigable sexual predator? And what does it say about Tahitian and Marquesan culture if we insist that Gauguin invented a fantasy because French colonisation had ruined everything that was beautiful?

Gauguin and Polynesia is an attempt to reinstate Polynesian women’s agency in their interactions with the travelling artist and to argue for a dynamic Indigenous-centred modernity in the colonised Pacific. Both are controversial efforts, speaking to the heart of current tussles in feminist and postcolonial scholarship.

For the past generation or so, these fields have been struggling to balance ways of recognising the power, autonomy and humanity of oppressed people while remembering, highlighting and censuring the violence of oppression. Every move seems to be a silencing of someone. Historians of domestic abuse, Aboriginal disadvantage, gender inequality and systematic racism know the dilemma all too well.

Thomas pulls off his ambitions convincingly, though he leaves some room for debate — much like a classic Gauguin painting, as he might add, always “beyond resolution.” Fortunately, readers today have several opportunities to ponder Gauguin’s work so they too may enter into debate with Thomas.

The NGA’s show, running in Canberra until October, is an exceptionally large and accessible exhibition of more than 130 pieces. Its catalogue presents most of the works in glorious reproduction. And the gallery has also recorded a compelling four-part critical podcast about Gauguin that delves into the ethics of displaying work by a deeply divisive artist.

Thomas opens Gauguin and Polynesia by explaining the state both of France and of the Tahitian archipelagos in the 1840s, the decade of Gauguin’s birth. Both places were rent by revolutions — failed revolutions of liberals and socialists in Gauguin’s homeland and successful revolutions of imperialists in the eastern Pacific. He then describes Gauguin’s upbringing: his surprising genealogical heritage of anarcho-feminism, his starting job in finance, his founding interest in the work of Camille Pissarro, and his marriage to a Danish woman named Mette Gad.

Very quickly we get a sense of Gauguin’s persona. Even before he stepped foot outside France, his letters to his wife reveal an exasperating narcissism. Within ten years of their marriage, Mette had not just given birth to five children but also been compelled to move them to her native Denmark in order to feed them. Gauguin often espoused the value of family units but never again joined or worked on behalf of his own.

In a representative letter from 1888 replying to Mette’s suggestion that he spend the summer with the family, he explained that he couldn’t do so since the cost of travelling to Copenhagen would equal that of three months’ living in Brittany, the noise of the kids would disrupt his creativity, his clothes would not suit Danish bourgeois values, and it was likely he’d just impregnate her once more. For the next decade he bitched and moaned to Mette about his obligations — on one occasion letting her know that he’d told the Tahitians she was dead — until she cut him off completely after their daughter Aline died in 1897.

So there is no need to follow Gauguin all the way to Tahiti to discover his misogynistic nature. Thomas is therefore less interested to demonstrate Gauguin’s misogyny in the Pacific — which is assumed rather than refuted — than he is to gauge how Pacific women coped with it when in Gauguin’s orbit. Of the middle eleven chapters that analyse Gauguin’s works, seven focus on his time in the Pacific and most of these feature women as the main characters.

An exemplary analysis deals with how Gauguin came to produce Vahine no te tiare (Woman of the Gardenia), the portrait of an unnamed female neighbour he had long wanted to paint. One day she was at his place flicking through photographs of European paintings, including Manet’s famously languorous, naked Olympia. “I asked her if I could paint her portrait,” Gauguin reported. “Aita (no) she replied, in a tone almost incensed.” The neighbour left, but returned an hour later in a different dress, with a fragrant gardenia behind her ear, ready to be painted.

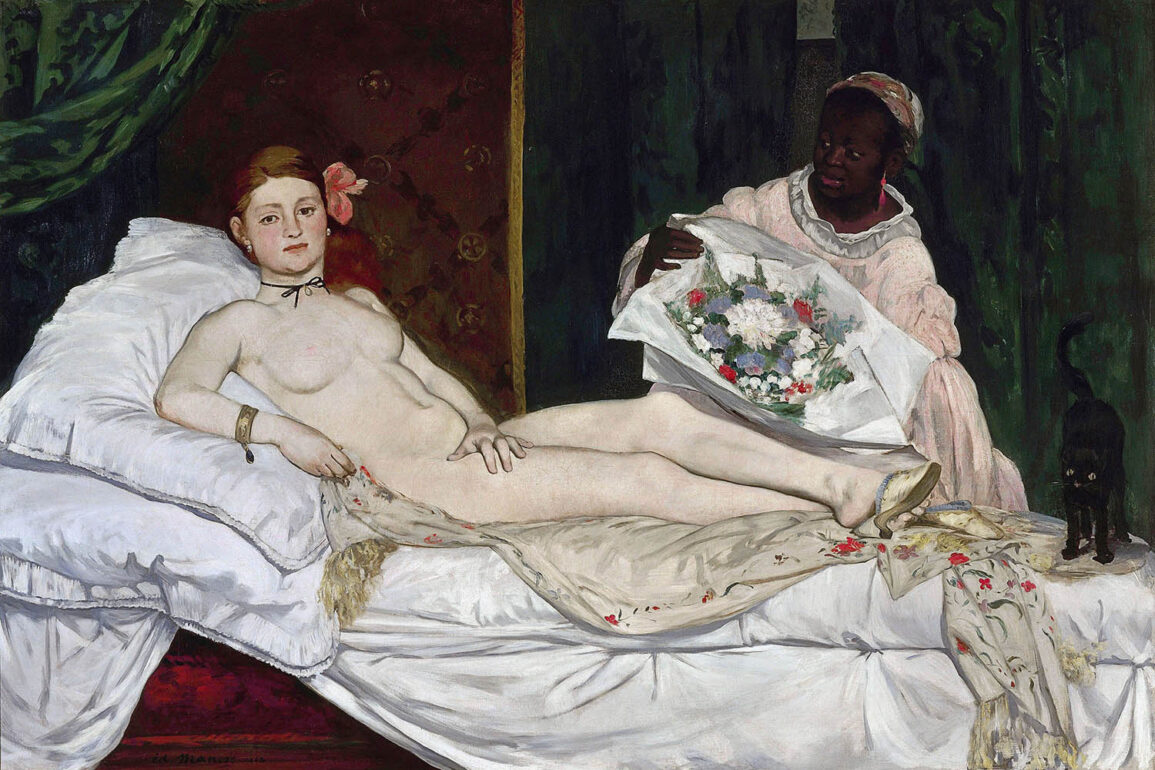

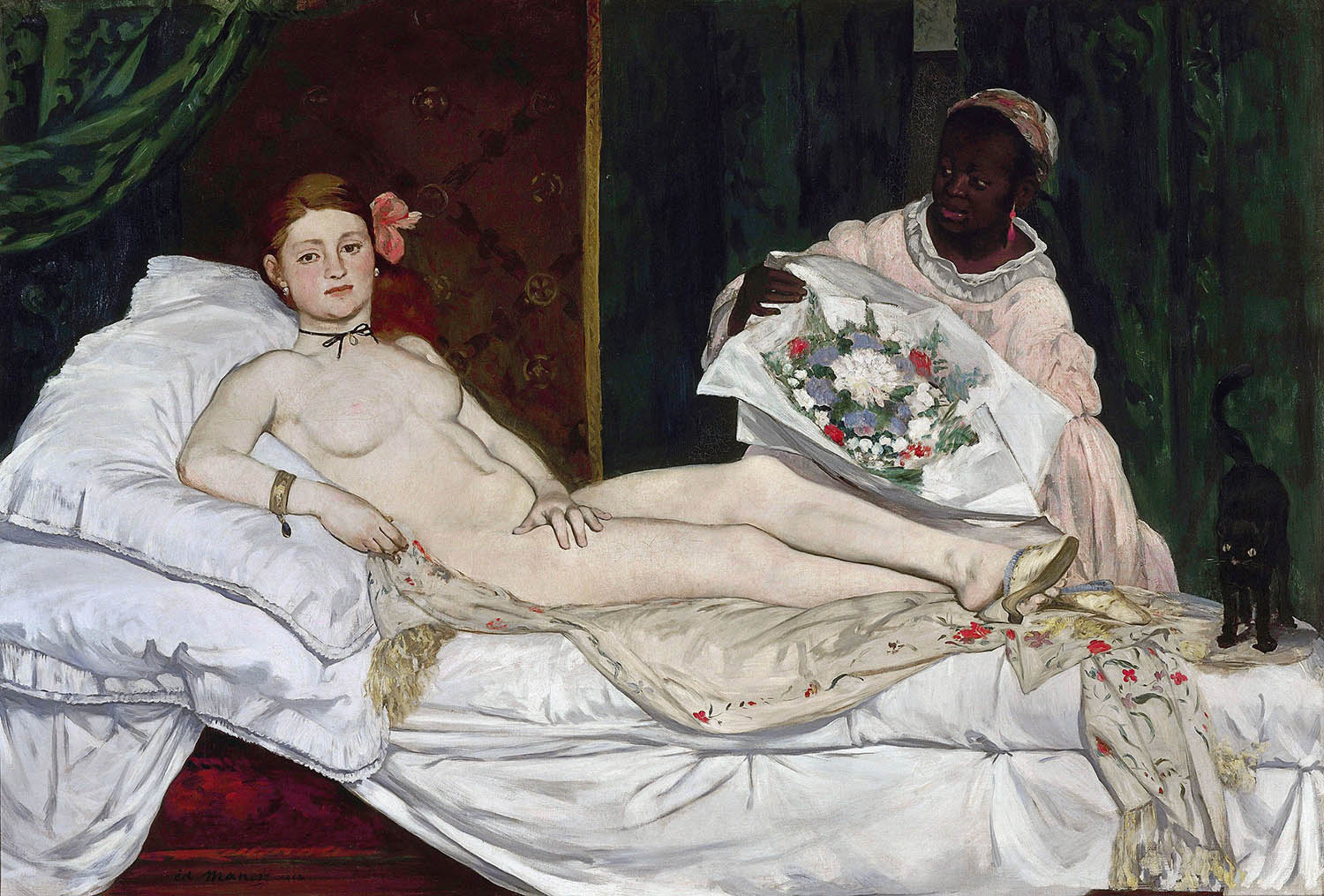

Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863).

Gauguin interpreted this change of mind as typical Polynesian caprice. “I worked hastily — I suspected her decision was not firm.” But Thomas suggests it was entirely firm, an instance of a Tahitian woman taking control of the circumstances of her representation, understanding what Gauguin’s craft could do and making sure she appeared the way she wanted (and not, presumably, like Olympia). The painting shows the neighbour sitting regally in a long blue dress, with white collar and flower, against a vibrant yellow and red background. Even Gauguin thought it showed the woman’s “robust fire of bounded strength.”

Elsewhere, Thomas discusses the meaning of the all-covering dresses that so many of Gauguin’s female models wore. His Polynesian subjects are usually either scantily clad or completely covered, indicating to most Western observers the two extremes of the Tahitian condition in the nineteenth century — exploited as sex objects or doomed by Christian fanaticism. But Thomas argues against recent convention, suggesting that these were in fact the two dominant modes of apparel favoured by Tahitian women at the time, the first for informal occasions among kin and the second for formal moments when in public. That most photographs from this era show them wearing what others have called “hideous muumuus” further underscores “their agency with respect to how they were represented.”

Thomas goes on to reveal how valuable cloth was in Tahitian society, explaining that Tahitians identified the cottons bestowed by the missionaries with the sacredness of tapa and therefore revelled in displaying yards of it over their bodies when occasion suited. The many paintings by Gauguin of fully draped women start to take on altered meanings with such contextualisation.

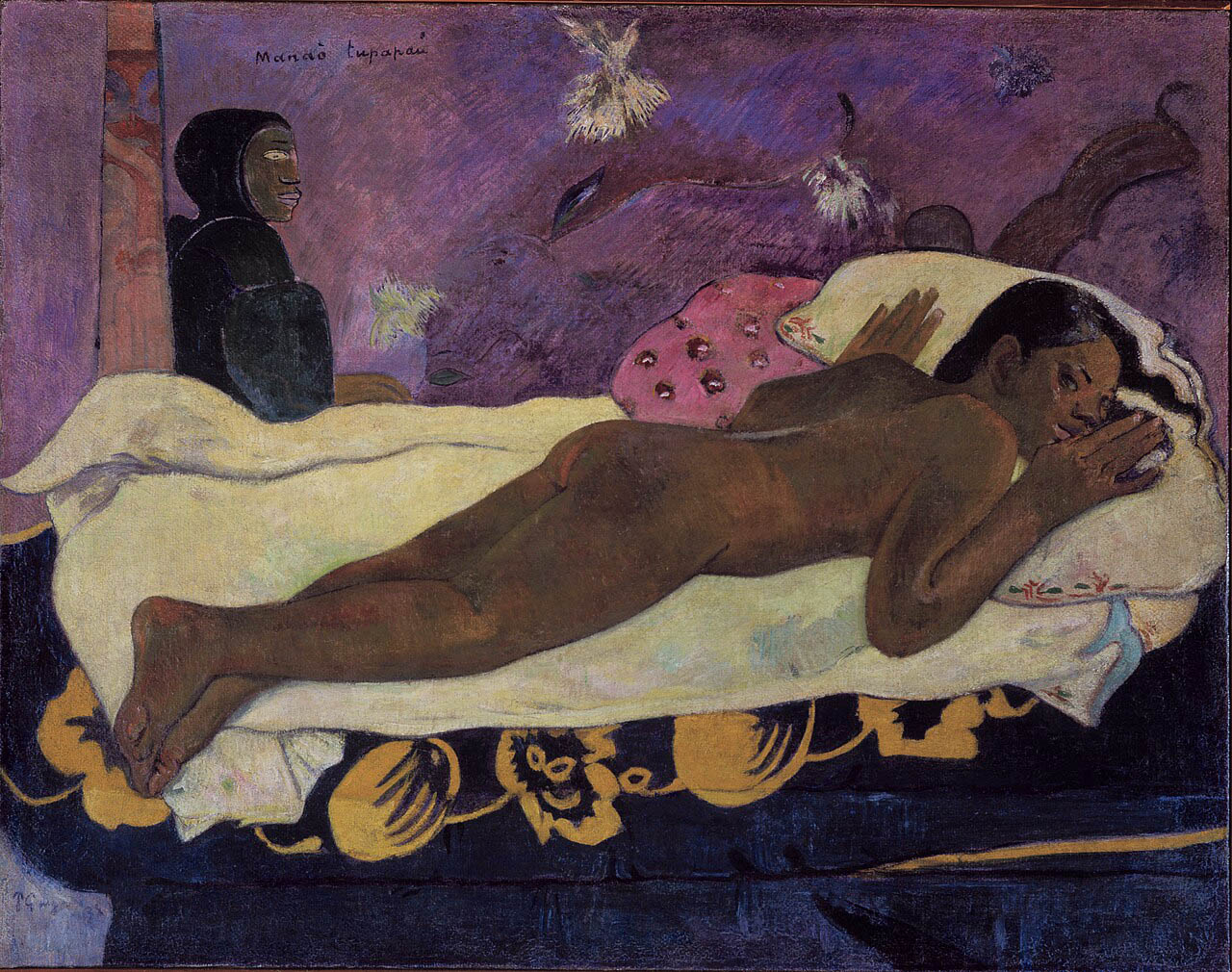

More controversially, Thomas addresses the making of Mana‘o tupapa‘u (Spirit of the Dead Watching), which depicted Gauguin’s first “child bride,” Teha‘amana. The painting has Teha‘amana stretched out naked on her belly with a fearful look on her face — a kind of flipped-over Olympia. Today, scholars focus first on the story of how Gauguin came to secure Teha‘amana as his mistress when she was only thirteen or fourteen (many years younger than Manet’s supposedly defiant sex worker). And, second, they usually describe this painting as proof of the terror felt by Gauguin’s subjects as well as his essentially brutal sexuality.

Gauguin’s Mana‘o tupapa‘u (1892).

By contrast, Thomas attempts to imbue Teha‘amana with as much of her own volition as he can muster — which at this historical and cultural remove, it must be said, is hard to do comprehensively, though she certainly appears in control of when she decided to be with him and the direction of their conversations.

More intriguingly, Thomas suggests that Gauguin played with terror in multiple ways in this work. He knew that European viewers would read the woman’s fear as that of exposure or even of rape (everything that Manet’s Olympia disdained). But Gauguin claims that local people would see that the most important figure in the painting was not Teha‘amana but the sinister hooded figure by her side. This figure is meant to symbolise the dead, sitting amid a highly animistic world of spirits and foreboding. The work is consciously ambivalent, Thomas argues, and the viewer who sees it only through European filters is the one with the problematic perspective.

Along with the notion of the passive Polynesian woman, the other key myth Thomas seeks to overturn is of a Pacific ruined by the French. He begins this theme by refuting the longstanding orthodoxy that Gauguin himself was disappointed by the colonial town of Papeete. This lore has Gauguin ruing Europeanisation and vowing to recreate a lost paradise in his imagination. Thomas claims Gauguin developed this stance many years later when he was writing an account designed explicitly to puncture the attitudes of European readers. At the time of his arrival in 1891, Gauguin was struck more by the beauty of the land and of aspects of Polynesian arts.

Thomas doesn’t leave Gauguin to explain what that beauty involved, however. Instead, he steps in to argue that the world of the French Pacific at the end of the nineteenth century was stunning not because it was pristine and nor because it was Westernised; rather, it was so because the Indigenous people were absorbing the impact of empire by interweaving new practices and old, remaking their society with attention to both history and the future. Gauguin revealed glimpses of this world, even when he didn’t know it, because he never entirely abandoned his commitment to Pissarro’s noted naturalism. And also because so many of his scenes and patterns accord with what we still see in the Islands today.

As a case in point, Thomas takes the painting Parahi te marae (Place of the Temple, reproduced at the top of this review). Some might suggest this work was an offensive jumble of Tahitian land and Marquesan design, but Thomas sees an affirmation, if unwitting, that the eastern Pacific at this time “was powerfully and permanently defined by Polynesian spirituality.”

Another instance of Polynesian survival is found in the tifaifai, the unique Polynesian quilts Gauguin often referenced in his works. (Teha‘amana is lying on one in Mana‘o tupapa‘u.) For Thomas, these artefacts were not the depressing signs of “deplorable assimilation” that so many scholars have described but rather “the very opposite: the continuation of a tradition of creating decorated fabrics… This sort of needlework may look like an imposed, European activity, but at a deeper level represents a new expression of ancestral values.”

Thomas goes on to complain, indeed, that one of the reasons observers have misread Mana‘o tupapa‘u so badly over the years is because they refuse to believe Teha‘amana understood traditional Tahitian beliefs about ghosts. If the sinister figure beside her can’t represent anything authentic about Teha‘amana’s ancient culture, then her terror can only be about Gauguin’s sexuality.

Thomas is careful to acknowledge dissenting opinions about Gauguin’s work. He hears younger Islanders who say that Gauguin’s engagement with the Pacific was exploitative (and interestingly shows that Gauguin’s mentor Pissarro felt this back in 1893). But he also wants to ponder the position of Pacific artists like Samoan Fatu Feu‘u, Māori Robin White and Tongan Dagmar Dyck, who have found something inspiring, at the least, in Gauguin’s remembrance of Polynesian forms.

Perhaps the bigger grievance for Islanders, as Cook Islander Jim Vivieaere once said, is that Gauguin’s paintings monopolise the world’s sense of Polynesia. Pasifika artist Rosanna Raymond echoed this sentiment in the NGA podcast when she sighed that Gauguin just “takes up way too much space in the Moana.”

Raymond is the curator of the SaVĀge K’lub installation that pre-empts the NGA’s current Gauguin exhibition in Canberra. A collaboration of more than thirty Pasifika artists, the installation celebrates the fusion of influences in modern Pacific art, which include responses to colonial intrusion.

Asked what she would prefer visitors to take away from a show about art from and of the Pacific, Raymond replies: “I want them to know the word Te Moana Nui-a-Kiwa… I want them to know that we’re losing species of migratory birds, that we’re losing our sea life because of the acidity in the water… that [the food] sold to the Islands are giving our people diabetes. And unless we really can engage and talk about these things, we are going to disappear before the land does.”

Raymond worked with the NGA on Gauguin’s World. She saw a chance to remind viewers of the pulsing, agentic and complex society that made Gauguin famous.

Thomas’s book does much the same thing. Both productions attempt to turn around the juggernaut of Gauguin’s name, using the man — with all his flaws — to direct fresh attention onto the power and continuity of his subjects. •

Gauguin and Polynesia

By Nicholas Thomas | Head of Zeus | $79.99 | 453 pages

Gauguin’s World: Tōna Iho, Tōna Ao

Curated by Henri Loyrette | National Gallery of Australia | Until 7 October 2024

SaVĀge K’lub: Te Paepae Aora’i — Where the Gods Cannot be Fooled

Curated by Rosanna Raymond | National Gallery of Australia | Until 7 October 2024