D ear Lala,

I am writing this letter mainly to congratulate you on the posthumous retrospective show in Sharjah this spring and to celebrate what we, as Pakistani women, have achieved today. Let me admit we owe you a lot for what we know of ourselves and the life around us. Thank you for the love and care you have shown in nurturing our young inquisitive minds; for training us to be observant and responsible. You taught us to think, to ponder, to acknowledge and rationalise our emotions and to be outspoken about them. Most important of all, you guided us to be useful in life.

The post-Zia generation, as we are often called, borrowing Iqbal’s expression is khaas in composition. We endured the ambiguities of social life at various levels. Our school uniforms changed from decent pleated veils pinned neatly on our shoulders to larger chaders that were hard to carry so mostly stayed in our bags only to be taken out at the time of inspection at home time. Swimming classes were ceased. The curriculum was abruptly changed, focusing on the two-nation theory, with India being the ultimate enemy and America, the dreamland. The caption on vegetable oil bought from the Utility Stores claimed it to be a ‘friendly gift from the people of the United States of America’. I won’t complain about the forced teaching of the Arabic language as the names of fruits, animals and counting learnt in Arabic class are now proving beneficial in encountering the misrecognition of being irreligious or rootless. I can see you smile on the sarcasm, here. During the ‘90s when we started college, student unions were banned and other socio-political activities that could help us groom into responsible, conscientious citizens were strictly scrutinised. The informal discussions on art, society and life, book reading sessions, excursions and field trips with you made college life exciting and helped us develop the much-needed colloquial sense. There were others too, some strong, intense, knowledgeable women, passionate about fostering an independent, free yet constructive spirit within their students. The best part was that you people never imposed any pre-conceived ideologies or solutions but rather highlighted the need to be wise, sensible and responsive to the situations that one might counter in an active social life. Such was your idea of feminism much larger than the body politics and other hullabaloos of ‘who will cook food and who would look for the lost sock’?

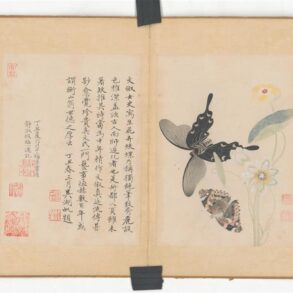

Back then, I was inspired by your simple, confident personality. Today, I am enchanted by your clarity of vision in art practice and pedagogy. Art, to you, was an act of personal inquiry and development. You always believed in intense, conventional, skill-enhancing training in your classroom. In your practice, you often used letters like marks as visuals to convey more abstract ideas. This is a popular notion being adopted by several contemporary Pakistani artists, which you had already employed over three decades ago. The ineffable alienness from physicality and materiality is the pinnacle of your art. This disorienting effect of formless representation of reality in your drawings and prints corresponds to the ideals of spirituality and metaphysicality. In purpose and impression, these small works on paper match the much larger colour field paintings of Mark Rothko that may fully consume human sensibilities. Only, you lead the viewer into the labyrinth through a thin streak or a flash line perhaps compelled by an inbuilt instinct of a teacher, a guide.

Unfortunately, I didn’t have a chance to discuss the Documenta 14 project with you. Allow me to share my insight. Rupak is the visual manifestation of music. The rhythm, recession and recurrence are mystical in nature only to be decoded by the gifted who are inclined towards sufi convictions. It is this fikr (thoughtful attention) and dervishi (the realisation of divine presence, the wisdom of the world and a large-scale missionary activity) that you practised and preached as Pakistani feminism.

With all my love and profound regards, Lala.

Yours Bano

June 24