Comics and graphic narratives have long been used to document the events of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, both by people visiting and reporting on the region, as well as by Palestinians and Israelis.

Prominent texts include comic book artist and journalist Joe Sacco’s Palestine, a detailed and visually chaotic account of the artist’s visit to Gaza and Sarah Glidden’s How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less, a travelogue detailing the cartoonist’s experience as a Jewish-American tourist in Israel.

(Just World Books)

There is also Guy Delisle’s Jerusalem, a story about living in Israel as a French-Canadian ex-pat, Palestinian artist Leila Abdelrazaq’s Baddawi, a historical and familial retelling of life in a Lebanese refugee camp and Palestinian political cartoonist Naji al-Ali’s A Child in Palestine, a collection of political cartoons featuring a now-iconic child named Handala. Israeli comic book artist Rutu Modan’s Exit Wounds recounts a love story set against the backdrop of a suicide bombing.

My previous writing explored how How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less reflects the artist/author’s complicated journey of self- and cultural discovery. As a Jewish American woman embarking on an Israeli-funded Birthright Trip, Glidden faces the violence enacted by the Israeli state. The book highlights Glidden’s quest for an authentic representation of Israeli and Palestinian lived realities, and her journey towards self-acceptance.

Personal memory and reflection — whether about identity versus culture or lived experience versus political unrest — has been a common thread across many graphic representations.

Read more:

Comics and graphic novels are examining refugee border-crossing experiences

Comics and illustration can be powerful forms of witness in their capacity to juxtapose text and image. While some illustrators or cartoonists have replicated antisemitic, orientalist and anti-Arab stereotypes, taking up the long-established visual negative stereotypical tropes, others seek to document, educate and empathize with victims. The use of negative visual tropes is not limited to graphic representations of Israel and Palestine, but a widespread phenomenon that manifests in various dehumanizing and hateful iterations across the visual arts. In this article, I focus not on the stereotypes we might find in comics related to Israel and Palestine, but instead prioritize how they are acting as networked resources.

Here, I discuss how creators have recently taken to social media to share short comics about what many experts say is the Palestinian genocide in real time.

Evocative illustrations

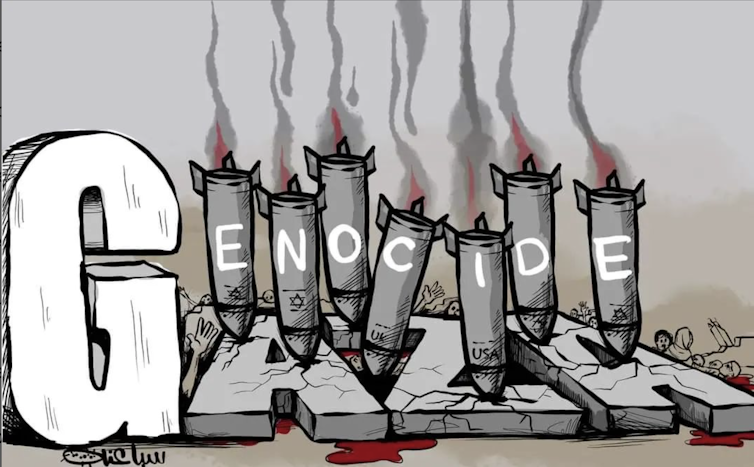

Palestinian artists such as Mohammad Sabaaneh (@sabaaneh on Instagram), author of Power Born of Dreams: My Story is Palestine and Palestine in Black and White, offers regular updates about events in Gaza while highlighting the artist’s criticism of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). In one post, Sabaaneh illustrates the word “Gaza” as if it were carved from large stones, and the word “genocide” spelled out across a series of rockets.

(Sabaaneh’s Instagram account, @sabaaneh)

Sabaaneh’s evocative illustrations have been featured in the Washington Post alongside the work of other Palestinian and Israeli cartoonists who are similarly sharing their critiques of the ongoing violence.

Sabaaneh, along with other Palestinian artists, are joined by western illustrators who are similarly using their social networks to draw attention to the IDF military incursion and its deadly effects.

Networks of care

These digital comics are circulated among platform users and provide an accessible outlet for processing emotion, showing solidarity and disseminating knowledge.

This is in line with media and communication scholar Fredrika Thelandersson’s research on mental health and social media, which argues that platform users “leverage platform affordances to create networks of care based in mutual experience.” It is also reflective of my work on how social media-based comics are operating as alternative mental health resources.

While the comics I point to in this article allow artists to process their feelings towards the conflict, they are also a crucial form of resistance to the ongoing attacks on Gaza and surrounding areas.

Cartoonist Lynda Barry, who uses the handle @thenearsightedmonkey on Instagram, has consistently used Instagram to showcase her protest, sharing what the artist calls “Ceasefire Balloons.” In these drawings, Barry uses balloons to represent the growing death count of Palestinian children. UN experts say 14,500 children have been killed by Israel’s military since early May following the Oct. 7 Hamas attack that killed at least 33 Israeli children.

(Barry’s Instagram account, @thenearsightedmonkey)

Barry’s posts are often met with messages of support and empathy from followers. Her activist work has also translated into a fundraising project, with paintings of “Ceasefire Balloons” being sold on Etsy in support of the Middle East Children’s Alliance.

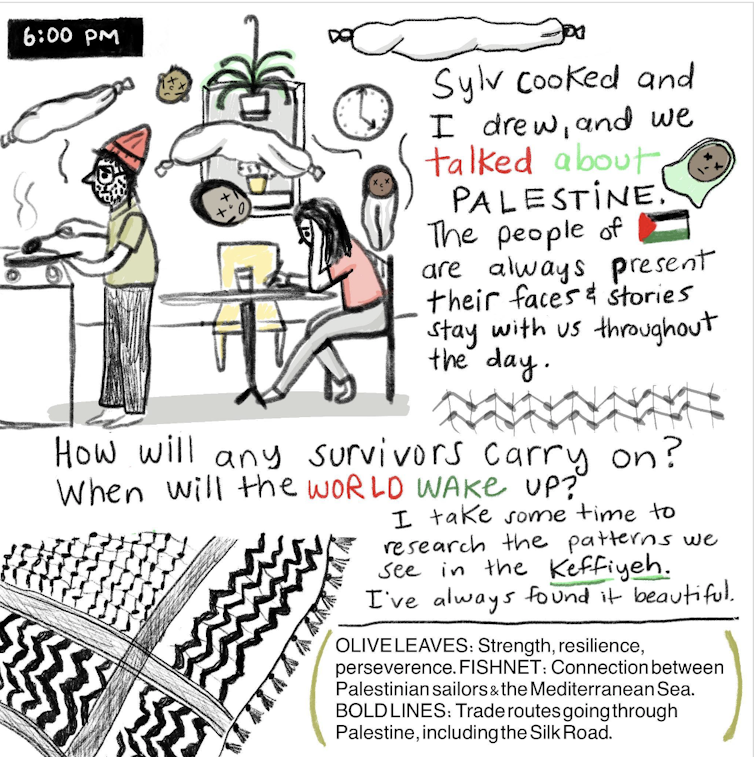

Montréal author and illustrator Sandra Dumais has also taken up a practice of creating comics that reflect her response to the ongoing attacks while simultaneously spreading messages of awareness and solidarity.

In her March 4 post, Dumais shares a single panel comic that reflects on the privileged realities of life in the West against the backdrop of what is happening in Gaza. Dumais has also leveraged her artwork as a means of raising funds.

Witnessing from afar

Artists like Barry and Dumais share their responses to the Palestinian genocide from a privileged western perspective that is secondary to the experiences of the Palestinian people who are living through it. These artists and others use the juxtaposition of text and image to represent the emotional toll of witnessing from afar, while also sharing messages that denounce the actions of the IDF.

(Dumais’ Instagram account, @sandradumaisbooks)

By doing so, these webcomics join global calls for a ceasefire and serve as a means of virtual activism by way of community-enacted resistance. Artists and platform users interact with and take up each other’s work as a way of creating a digital social movement.

‘Being together alone’

This is reminiscent of what social media scholars studying mental health communities, such as Natalie Ann Hendry, refer to as “being together alone,” where people working through experiences find community, solidarity and support in popular online spaces.

I point to these western artists as an example of how comics and social media are working as a conduit for amplifying the experiences of marginalized communities across geographical borders.

Comics not only show what is happening in Gaza through illustration, but also provide an alternative to mainstream perspectives. This means two things: these webcomics are functioning as emotional outlets for the artists, as well as intentional acts of solidarity and resistance.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content