Following its most recent NFT (non-fungible token) auction in New York, representatives for Christie’s say they see a maturing of the digital art market on the blockchain, nearly three years after the massive peaks and succeeding troughs in NFT valuations in 2021-22. This month’s sale—of SOURCE [On NFTs], a limited edition of generative art pieces created by the British artist, writer, crypto art and NFT pioneer Robert Alice—produced the largest sale by volume to date on Christie’s 3.0, the auction house’s on-chain platform for selling NFT art, since its launch in September 2022. It also brought a 20% rise in the number of customers registered as holders of digital wallets that enable them to buy NFTs on the site.

“We’re excited by the influx of new clients,” Nicole Sales Giles, director, digital art, a Christie’s, tells The Art Newspaper in reference to the Alice sale. “People are really around for the content and around for the art, as opposed to … making a quick buck,” Sales Giles says. Acquisitions in the past 12 months of digital art by institutions were cited by Sebastian Sanchez, digital art sales manager at Christie’s New York, as governing factors in the new mood. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, have all made their first acquisitions of NFTs in the past 18 months—while Alice had an NFT acquired by the Centre Pompidou in the lead-up to the SOURCE (On NFTs) sale.

Alice created SOURCE using an algorithm trained to produce outputs from data sets of 30 texts associated with the ten-year history of NFTs as well as the 2,500-year prehistory of democratic and libertarian writing, cryptography and science fiction—from Laozi’s Tao-te Ching (around 400BC) to Satoshi Nakamoto’s Bitcoin Whitepaper (2008) by way of George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) and William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984)—that produced the philosophical “outsider” foundations for the blockchain and the crypto currencies and NFTs that sit on it. It was the first time that the 257-year-old auction house had sold generative art of this kind at auction and also the first time it had run a Dutch auction—an approach familiar to the NFT world—where the bidding starts at a high price and is progressively reduced until a buyer or buyers emerge.

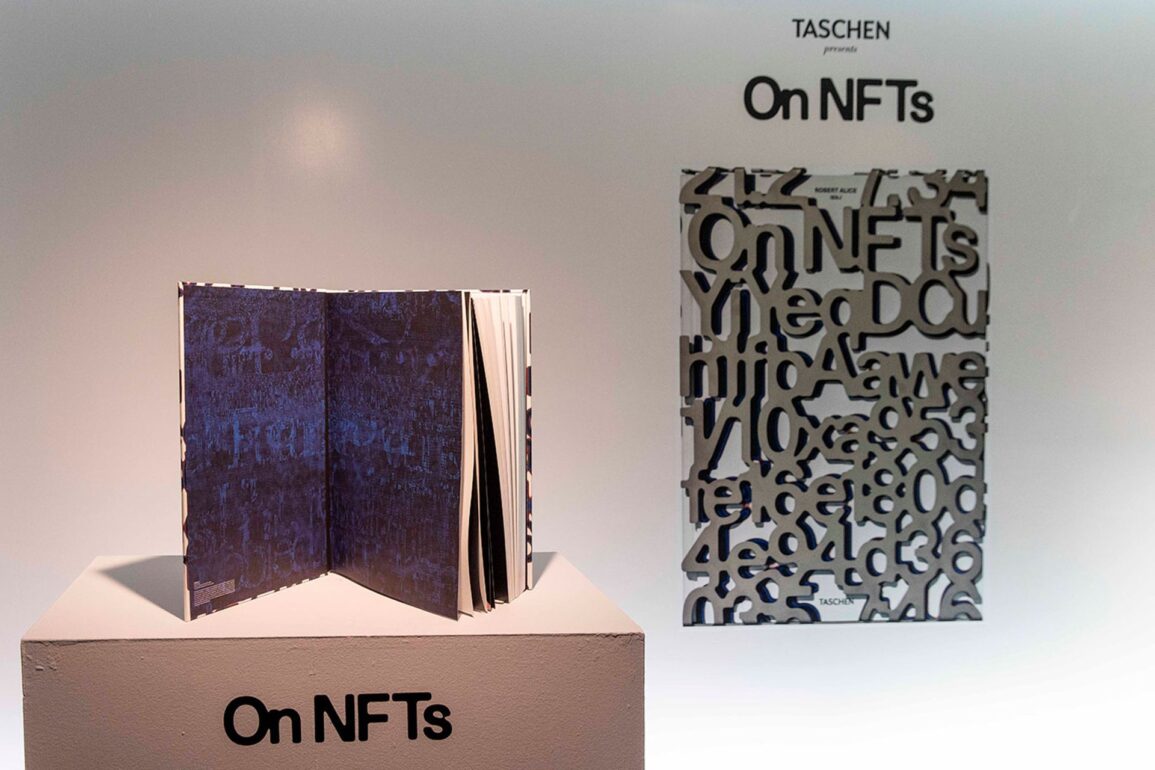

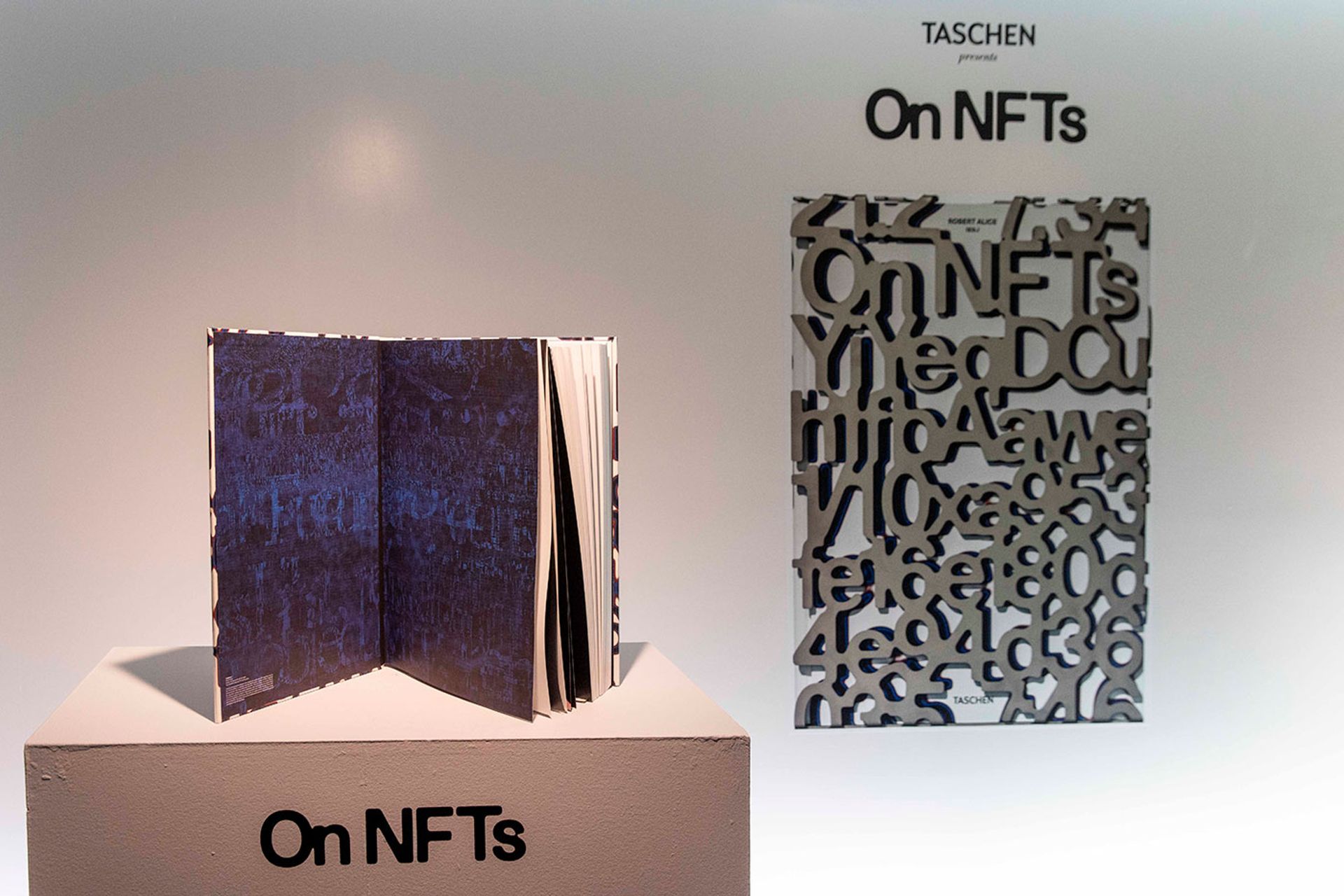

SOURCE is the “artistic twin” to the recently published On NFTs, a scholarly, large-format survey of NFTs, edited by Alice and published by Taschen (a smaller trade edition will follow). Alice had been working on both book and artwork for nearly three years—writing and editing in the morning in their London studio; working on SOURCE and its algorithm in the afternoon. The two are deeply intertwined.

The endpapers to Robert Alice’s large-format study On NFTs are outputs from the SOURCE [On NFTs] generative algorithm Courtesy Robert Alice

The high price set for the SOURCE auction was 5 Ether (ETH), equivalent to around $20,000 during the week the sale was up (12-19 March) and a low, or resting price, of 0.3 ETH, equivalent to $1,200. On 12 March, the price was lowered in increments over two hours until the price landed at its resting price.

The first ten buyers bidding 1.5 ETH ($6,000) or more in the auction also acquired one of the first ten, signed and numbered, editions of On NFTs, known as the Hard Code edition, and encased in a sculptural stainless steel cage built from linked letters and numbers. (The book’s endpapers are printouts of NFTs created using the SOURCE algorithm.) During the auction, 125 artworks were minted, making it the largest sale by volume to date on Christie’s 3.0, and generating over $200,000 in sales.

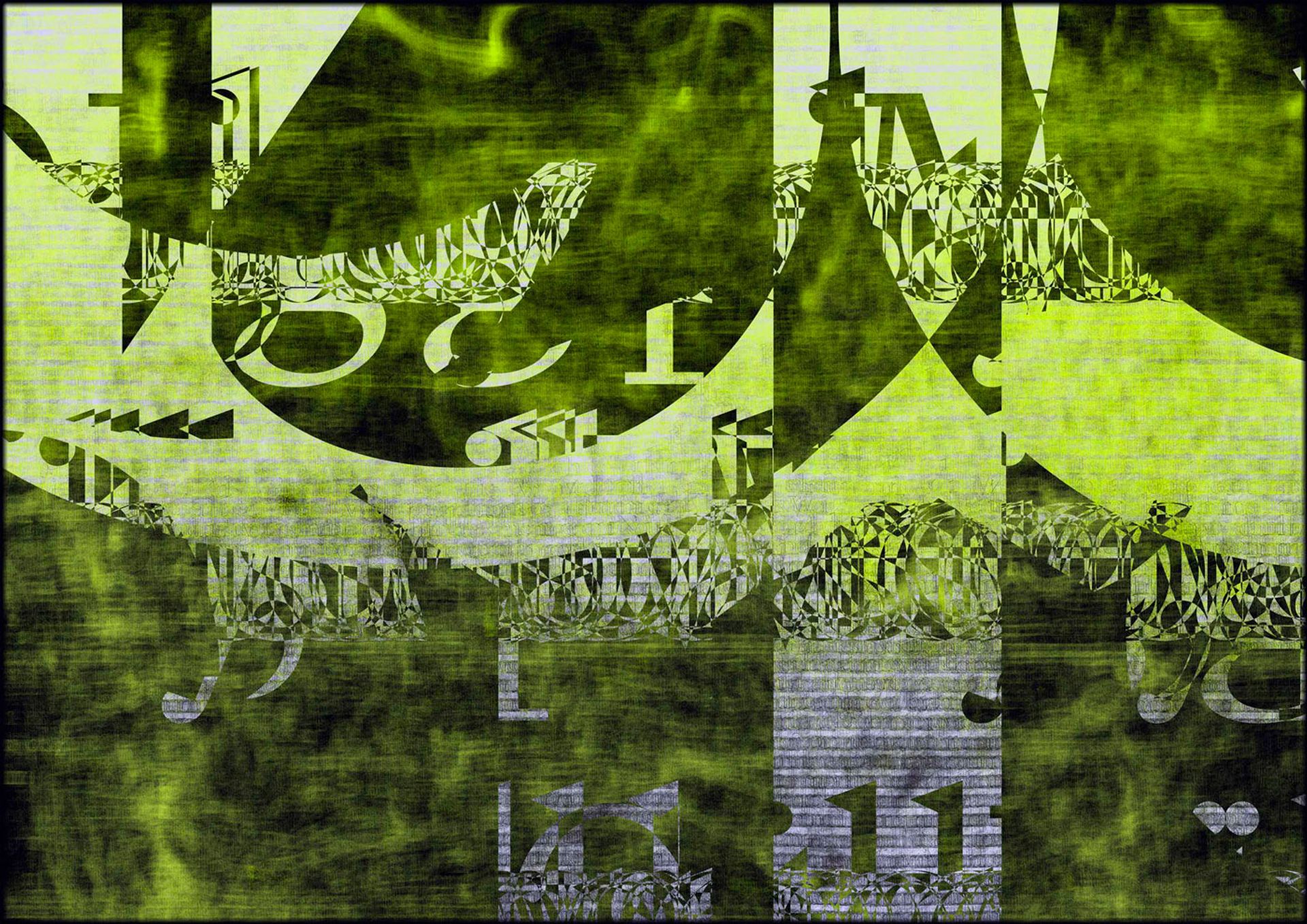

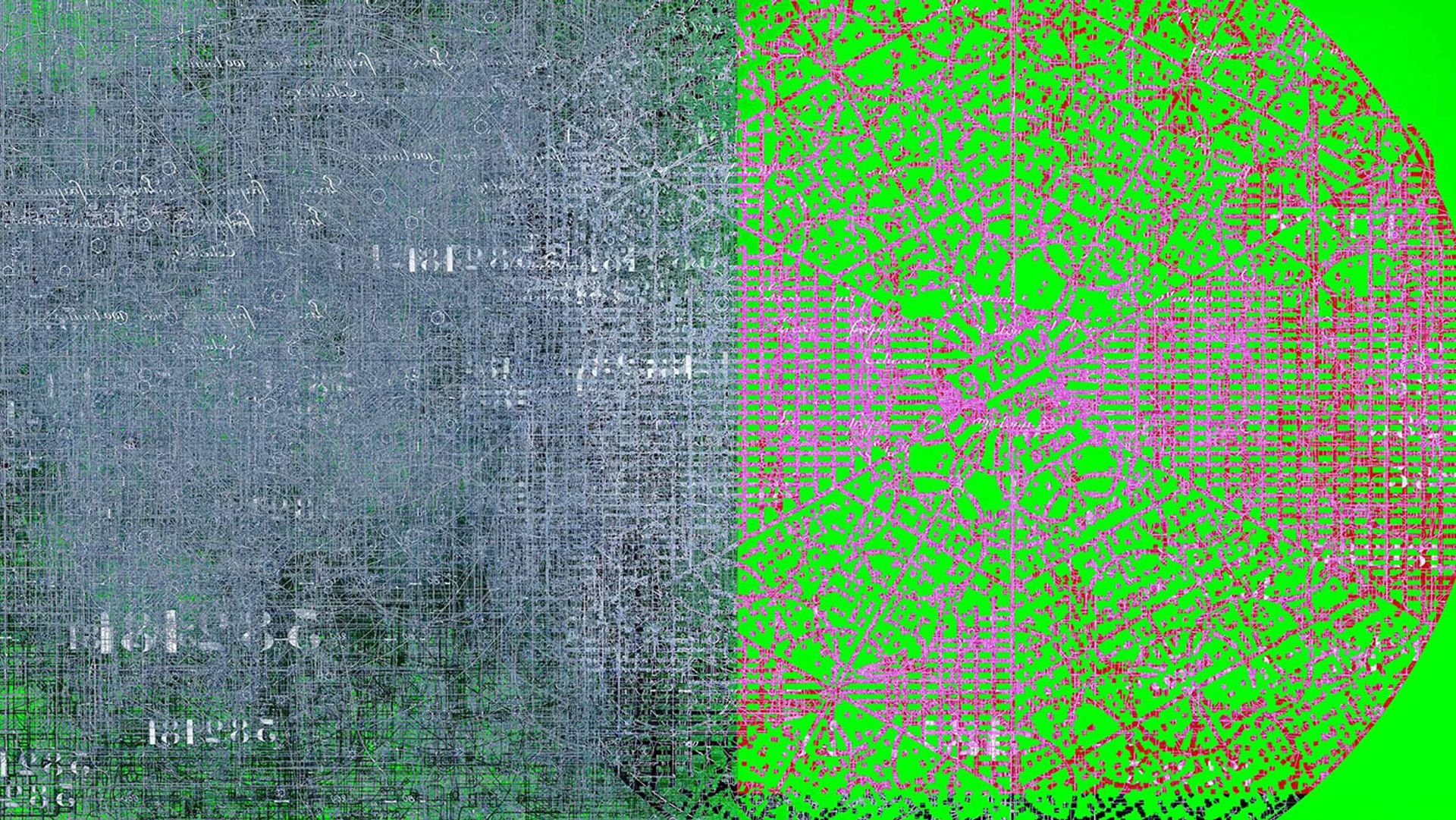

Founded on text: one of the test outputs of Robert Alice’s SOURCE [On NFTs] Courtesy Studio Robert Alice

The bidding process

When bids were placed in the SOURCE auction, the purchase was immediate, minted as an NFT on the Ethereum blockchain, while at the same moment the linked artwork was generated by the SOURCE algorithm. Artist and auction house ran through a large number of test outputs before the sale to demonstrate the conceptual and aesthetic foundations of the algorithm, and hung printouts of many of these in the gallery at Christie’s New York for the sale’s launch. Potential buyers were informed by these tests, but the first time they knew of the appearance of their work was after making a bid and seeing their NFT minted and the generative artwork produced by Alice’s algorithm.

The first minting, and first copy of the Hard Code edition of On NFTs went to PleasrDAO, one of the leading collectors in the market, a Decentralised Autonomous Organisation that, according to its entry in On NFTs, “has focused on NFTs with art and historical importance” and is know for purchasing “a single copy album by the Wu Tang Clan for $4m, an NFT representing the first edit of Wikipedia and spent over $5.4m for Stay Free (2021), an NFT created by Edward Snowden”. PleasrDAO was one of two buyers who bought at the starting price.

PleasrDAO posted on X (formerly Twitter), with a tongue-in-cheek reference to the book’s large format: “To mark this historic occasion, PleasrDAO has committed to printing an inhabitable version of the book so big that it will be the tallest building in NYC (probably the world) and will be the home to our iconic collection and future activities.”

Digital firsts

Alice and the digital art team at Christie’s are used to creating firsts together. In October 2020, Alice’s Block 21 (42.36433° N, -71.26189° E) from Portraits of a Mind (2019-present) was sold by Christie’s New York, marking the first time an NFT had been transacted through an auction. Block 21 is a physical painting and was sold with a linked NFT that acts as a permanent certificate of its transaction on the blockchain. It made $131,250, more than seven times its high estimate of $18,000. That sale paved the way for the headline-grabbing $69.3m sale of Beeple’s Everyday: The First 5000 Days (2021) at Christie’s in March 2021, the first standalone NFT work of art to be sold by an auction house. Three months later Alice co-curated Natively Digital, the first curated group NFT sales at a major auction house, for Sotheby’s.

Alice is a trained art historian, with experience in writing and editing art catalogues, and much concerned with the power of books and libraries and with the infinite archive of Jorge Luis Borges’s 1941 short story “The Library of Babel”. The research Alice did for On NFTs carried them back past the ten-year history of NFTs into the intellectual and aesthetic underpinnings of the blockchain and cryptocurrency world that gave rise to the format.

Robert Alice (right) with Cosmo Lindsay, project manager and head of research at Studio Robert Alice, at the launch of the auction of SOURCE [On NFTs] at Christie’s New York on 8 March. The artworks are prints of test outputs of Alice’s generative art algorithm Courtesy Robert Alice

In the introduction to On NFTs, Alice makes the arresting point that no image can exist on the blockchain without text. “Whether it is a code-based on-chain work, or a hyperlink to a decentralised file server,” they write, “text is the current and currency that creates and secures NFTs.”

Alice worked with James Parker Healy and Michael Villere at Digital Practice, the New York-based Web3 and NFT tech specialists, on the SOURCE project, to train a natural language programme (NLP) to work with the historical texts. Digital Practice also collaborated with Christie’s 3.0 to ensure the minting of NFTs worked through the auction house’s website.

The output images for SOURCE [On NFTs] are richly pigmented and conceptually profound, a pushing together of opposing, sometimes unrelated words, texts, letters, fragmented letters and glyphs (based on the text font used in the book On NFTs) in which Alice achieves their ambition of breaking away from the prevailing NFT aesthetic—a taste for tech and gaming nostalgia that tends towards pixelated avatars—and put, as they say, “more meat on the bone” of NFT art.

“Portraits of a Mind”

Alice’s artistic concern with code and cryptography is also at the heart of an earlier large-scale work, Portraits of a Mind, which is made up of 40 paintings and NFTs, plus corresponding NFT editions, with each painting micro-engraved with 322,048 digits of the 12.3 million-digit original code for Bitcoin cryptocurrency. The mind portrayed is that of Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonymous person or persons behind Bitcoin. Each constituent grouping of painting and NFT has a “Block” title containing a latitude and longitude grid reference to a place significant in the history or prehistory of blockchain and crypto, where cryptography and privacy-enhancing technology have come to be seen as tools for political change.

As Alice tells The Art Newspaper: “The various geographic sites [in Portraits of a Mind] are meant to show the historical and continued tension between the right of the individual and the encroachment of the state in the private lives of citizens that has categorised the political basis for cypherpunk and then crypto movements.”

Block 21 (42.36433° N, -71.26189° E) from Portrait of a Mind—the work sold at Christie’s in 2020—carries the grid reference for Brandeis University, in Waltham, Massachusetts. The university was named after the lawyer Louis Brandeis, co-author of the seminal 1890 Harvard Law Review essay “The Right to Privacy”.

The painting element of Robert Alice’s Block 34 (51.895167° N, 1.4805° E) from Portraits of a Mind (2019-present), installed on the principality of Sealand, in the English Channel Studio Robert Alice

Another piece from the series, Block 34 (51.895167° N, 1.4805° E), represents Sealand, the independent principality set up on an abandoned sea fort in the English Channel off the coast of Essex; an entity which has for six decades stood for independence and pirate radio ethos and which has become closely aligned with the Web3, blockchain and crypto communities. Alice has exhibited Block 34 (51.895167° N, 1.4805° E) en plein air, on Sealand’s helipad.

The work acquired by the Centre Pompidou this month, Block 10 (52.5243° N, -0.4362° E), is also from Portraits of a Mind. The location referenced is Fotheringay Castle, in Northamptonshire, the place of the final imprisonment, trial and execution of Mary Queen of Scots, in 1587. Mary—who had grown up at the French court and who had been for one year, until the premature death of her husband, King Francis II, Queen Consort of France—used codes and ciphers to communicate, most notably when attempting to correspond with her political supporters during the 19 years that her cousin Queen Elizabeth I kept her prisoner in England. And it was the breaking of Mary’s codes, and with it the discovery of her complicity in the Babington Plot to assassinate Elizabeth and replace her with Mary, that condemned the Scottish queen to trial and execution.

To Marcella Lista, chief curator of new media art at the Pompidou, Block 10 and the Portraits of a Mind series as a whole show “the invention of cryptocurrency in a historical perspective that goes beyond its mere economic understanding”.

Infinite library: Robert Alice’s 382181_Garden City (28 June 2023) from the artist’s Blueprints series, made in response to the archive of the Monnaie de Paris, the city’s historic mint where Alice showed hybrid physical and digital works in 2023 Courtesy Robert Alice

Paris was also the scene of Alice’s first monograph show in summer 2023, at the Monnaie de Paris—the headquarters of the French mint—where the exhibition gathered hybrid physical and digital works including pieces from Portraits of a Mind and from a new series, Blueprints, where drawings from the Monnaie collection are, as Alice’s website puts it, “interwoven with diagrams, patents, network maps, literature and digital aesthetics taken from the history of blockchains to present imagined structures that present the collision of these two at time competing systems of thought—the centralised and the decentralised”.

A slow history of a fast art

On NFTs, which Alice started working on in late 2021, is based on the artist’s desire to capture the serious work that was being done in the NFT space, “to take a slow look at a fast art”. At the time, the news media was most concerned with the huge prices being made by sales like Beeple‘s Everydays and the artist Pak’s Merge—where 28,983 buyers minted NFTs on the Nifty Giftway platform for a combined total of $91.8m in December 2021—rather than the proof of work, the artistic concept and process, and the ground-changing patterns of ownership that those projects and many others represented.

The interesting background to the Beeple Everydays sale in 2021, Alice says, was what attracted the collector Metakovan to buy the piece. “The reason that he liked Everydays was that it was a proof of work,” Alice says. “An artist had got up every day for 15 years and produced a new work. And whatever you think about Beeple and his work, that’s incredibly powerful. We lionise On Karawa in his I Got Up series. We lionise Roman Opalka and his One to Infinity series, [as] cornerstones of conceptual art. And Beeple is the update of that for the contemporary age.”

Decentralised co-creation

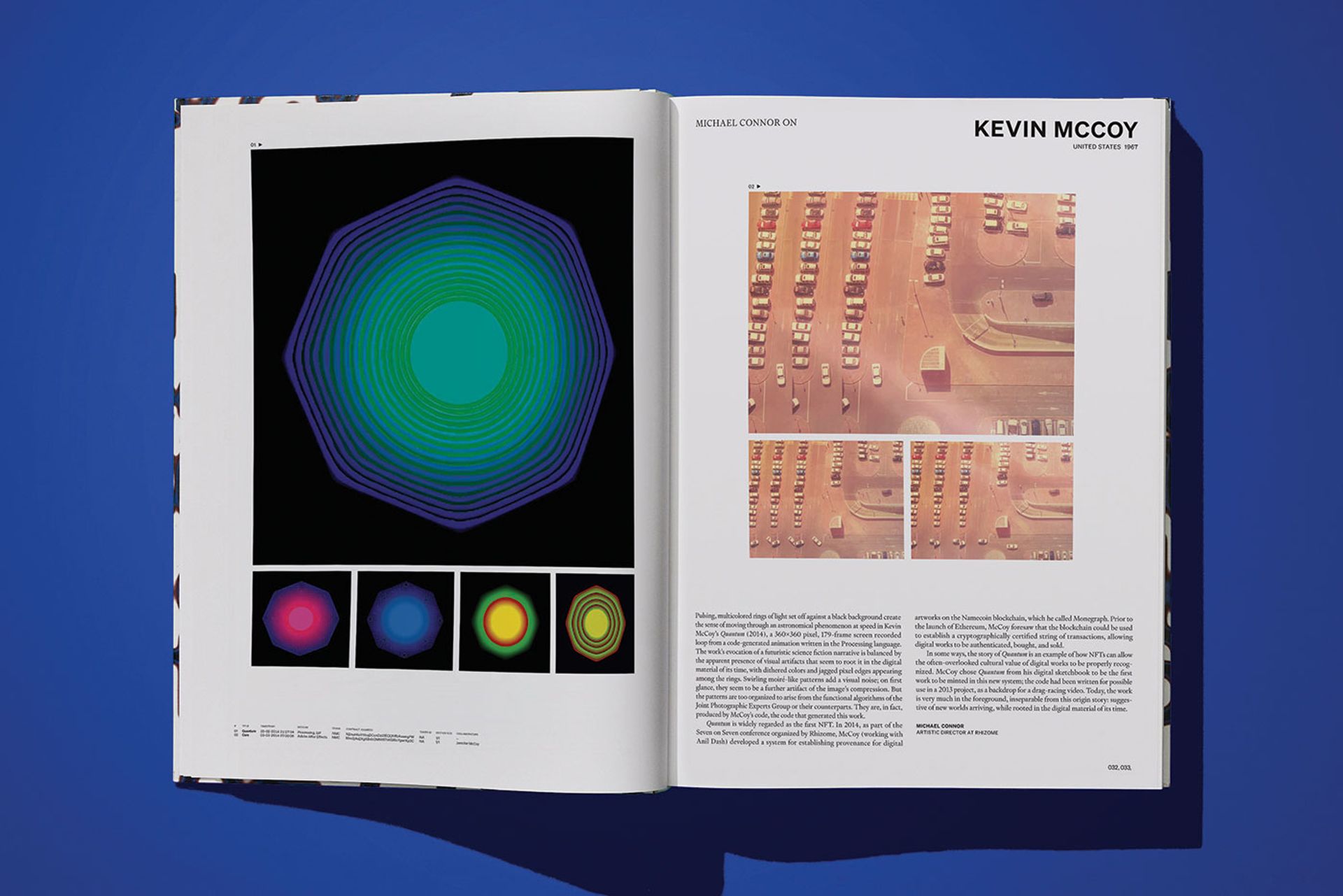

On NFTs is ordered as a series of just over 100 artist profiles interlaced with essays by Alice and other contributors on topics including Quantum, Kevin McCoy’s foundational 2014 NFT, crypto art, algorithmic (or generative) art, smart contracts, artist process and collecting.

The profiles of artists and other NFT stakeholders were commissioned in a most crypto community way in what Alice describes as “decentralised co-creation”. They started by asking 20 people that they and their collaborator Cosmo Lindsay—project manager and head of research, who Alice describes as “extraordinary” and credits in the “Editor’s thanks” section as the “nervous system of this book and its heartbeat”—found “there was a historical consensus about”. They asked this group of 20 each to suggest back three artists they admired and three they felt were overlooked. The process was then repeated, generating a long list of 900 names. If an artist was voted in four or five times, they went into the book. The result of this community recommendation model was that even to Alice, an expert in the field, many of the artists profiled in On NFTs were completely new.

On process

As part of Alice’s desire that On NFTs should serve as a bridge between the crypto world and the traditional art world and art history, the book places great emphasis on artistic process as a way of demystifying a sector populated with acronyms, specialist knowledge and technical terms. The chapter “On Process” is, Alice says, “really the soul of the book”.

With traditional art “it’s very easy to see how things are made and therefore appreciate their craft”, Alice says. “Whereas digital artwork can go through complex processes [before being] filtered into a bitmap raster, a pixel grid… And it’s very hard unless you’re deeply educated in the space to understand how things are made and the materiality of them from a digital point of view.”

They approached six artists—including Beeple and Refik Anadol—who use NFTs to certify on the blockchain work created with numerous techniques “from AI through to very complex on-chain work through to Erick Calderon’s Chromie Swiggle, which is very simple”. These artists were asked to open their studios or their computers and to demonstrate their processes. “The ‘On Process’ chapter dives into that,” Alice says, “it’s a way for people to really understand the craft-based approach to a lot of NFT practices, which is almost more technically advanced and complex, and requires a higher level of craftsmanship than even our greatest painters, because of the computer science aspect”.

Respect to the work: The opening pages of the profile in On NFTs of the artist Kevin McCoy and (left-hand page) his world-first NFT Quantum (2014) Artwork: Courtesy Kevin McCoy; Book: Courtesy Taschen

A catalogue raisonné

Alice sees the blockchain as the latest innovation in the arts of record-keeping and publishing, while the presence of NFTs on it as records of artistic provenance makes it so much more than an economic ledger. And they consider the cataloguing that went into On NFTs as central to its character.

Alice and Lindsay say they “made this decision very early on that … we wanted the book to [show] the same kind of respect to the work as you get through a catalogue raisonné … And of course the blockchain is the world’s ultimate catalogue raisonné [as a record of provenance] … the world’s first truly decentralised public library, where artworks are time-stamped now down to the very second. The days of ‘c. 1970s’ [in a catalogue entry] are gone. There is this perfect ordering of things, which is fundamentally new.”

Generative art for all

The real interest for Alice in the headline-making sale of Pak’s Merge sale, in the eyes of some the high-water mark of the 2021 NFT boom, lies not in the $91.8m price but the fact that Pak had gone online and sold nearly 29,000 artworks at a low price, through multiples of units worth $300 and upwards. It demonstrated a new mass distribution model for the art industry.

Looking forward from the SOURCE [On NFTs] sale at Christie’s, Alice sees the power of the “NFT space to open up a world where you can create generative artwork”. They add: Suddenly, it’s not just the titans of industry that are art collectors, but it’s everybody who can build an art collection and share it. And that is fundamentally powerful in terms of the future viability and democratisation of art and how far it can go.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content