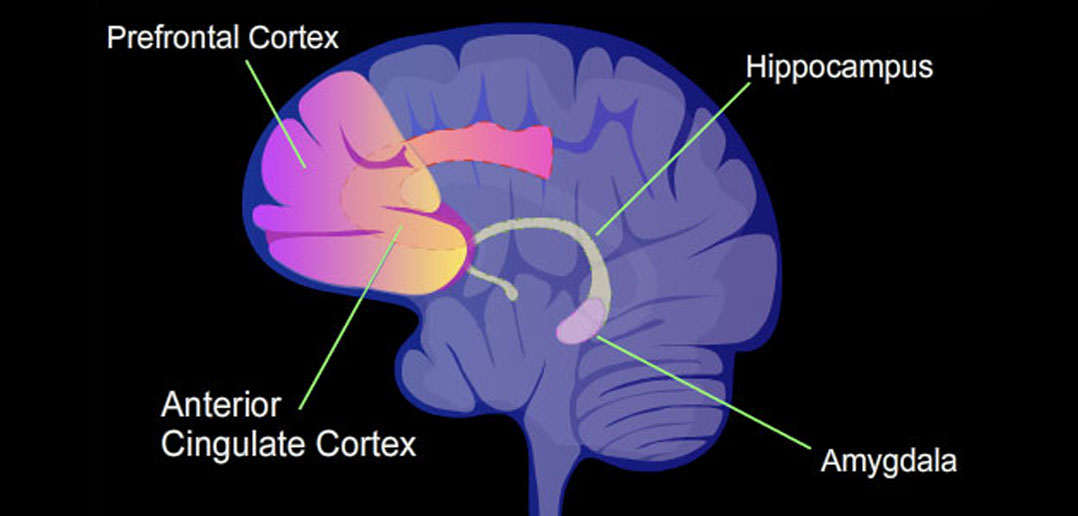

In a new study published in Science Advances, researchers at Northwestern Medicine discovered that the brain regions used for thinking about other people’s thoughts are linked with ancient, emotion-related structures deep within the brain—specifically, the amygdala. Their work shows that a network involved in social understanding is directly connected to parts of the brain that guide emotional learning and social behavior—a finding that may one day lead to improved treatments for conditions such as anxiety and depression.

The researchers were motivated by a desire to understand the neural basis of social cognition, which is a fundamental aspect of human intelligence and is impaired in several psychiatric disorders. Prior research had established that a network of brain regions, often referred to as the “social cognition network,” becomes active when people engage in tasks that require thinking about others’ mental states.

Earlier work by these researchers had demonstrated this network to be separate from a similar, adjacent brain network that is instead recruited during episodic projection and scene construction, i.e., thinking about the past or future. Separately, extensive animal research had identified the amygdala, particularly its medial nucleus, as a core structure responsible for controlling behaviors such as aggression, parenting, and mating.

The current study aimed to bridge these two lines of research, asking how, or if, the social cognitive network that enables humans to so expertly navigate social interactions connects to this evolutionarily older area in the amygdala that has been shown to be crucial for social behaviors.

“A major part of our mental lives is taken up thinking about other people: what is she thinking? How are they feeling? What did he mean? How is she going to react? and so on,” said study authors Rodrigo Braga, (an assistant professor at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine) and Donnisa Edmonds (a PhD candidate at the Northwestern Interdepartmental Neuroscience program).

“There is a large-scale network called the social cognition network that becomes active when we engage in this kind of thinking. On the other hand, the amygdala is a brain structure that is implicated in many different psychiatric conditions. Multiple studies have linked the amygdala, particularly a small part called the medial nucleus, to the control of social behaviors including parenting, aggression, mating, etc.”

“So, we were interested in understanding the link between these two, specifically which parts of the amygdala were connected to the social cognitive network and how specific these connections were,” the researchers explained. “Since the amygdala is a part of the brain that is typically difficult to study with fMRI, because of its small size and because of where it is positioned deep inside the brain, we reasoned that having high-resolution fMRI data might allow us to see connections between the amygdala and social cognitive network with greater specificity.”

Specifically, the researchers employed a high-powered brain imaging technique called 7 Tesla functional magnetic resonance imaging. This technology allowed them to acquire images with an exceptionally high resolution, enabling them to visualize brain activity in much finer detail than traditional fMRI. They used this technique to analyze brain activity in a small group of six participants. These participants had been extensively scanned as part of a larger project called the Natural Scenes Dataset. Each person underwent multiple scanning sessions, providing a large amount of data for each individual.

The researchers also used a second, independent sample of eight individuals, who were scanned using a more conventional 3 Tesla fMRI. The researchers focused primarily on “resting-state” brain activity, meaning the participants were not engaged in any specific task but were simply lying still in the scanner. This allowed the researchers to examine the intrinsic connections between brain regions, independent of any particular task demands.

In addition to the resting-state data, the second dataset of eight participants also included brain activity data recorded while they performed specific tasks designed to tap into social cognition. These tasks involved thinking about another person’s false belief (e.g., understanding that someone might believe something that isn’t true) or rating the emotional pain someone might experience in a given situation (e.g., after losing a pet).

These tasks allowed the researchers to compare the brain activity patterns observed during social cognition with the resting-state network connections. The participants in this second dataset also performed a task targeting episodic projection, which involved imagining and constructing scenes in their minds.

The fMRI data was analyzed using a technique called functional connectivity analysis. This method measures the degree to which the activity of different brain regions fluctuates together over time. Brain regions that show highly synchronized activity are considered to be functionally connected, suggesting that they work together as a network.

To identify brain networks, the researchers used a two-pronged approach: a “seed-based” method, where they started with a known brain region and mapped its connections, and a data-driven clustering method, which groups brain regions based on similar activity patterns. This dual approach, replicating previous findings, allowed them to reliably distinguish two distinct but closely intertwined brain networks: the social cognitive network and the episodic network, which supports processes such as recalling past events and mentally constructing scenes.

The researchers found that the social cognitive network is selectively connected to anterior portions of the medial temporal lobe, including regions within the amygdala. “There’s a group of brain regions, known as the social cognitive network, that work together when someone is thinking about other people’s thoughts and feelings,” Braga and Edmonds told PsyPost. “Our study shows that this network is connected to a number of structures within the amygdala, but in particular to the medial nucleus, which is a key structure that controls many social behaviors.”

In contrast, the network related to episodic memory was connected to more posterior portions of the medial temporal lobe. This separation suggests that even though the brain areas responsible for remembering past experiences and imagining future ones are adjacent to those involved in social thinking, they may serve different functions by linking with distinct deeper brain regions.

An especially interesting observation was that when the researchers placed seeds specifically in the amygdala regions identified as part of the social cognitive network, they reproduced the full distributed pattern of the network. In several cases, regions in the amygdala that were connected with the social network were bilateral. These areas appeared to be concentrated in parts of the amygdala known from studies in animals to be important for processing social signals.

“One surprising aspect was that the social cognitive network included multiple regions within the amygdala,” Braga and Edmonds said. “This is interesting because the amygdala comprises multiple nuclei with well-studied functions: some are input structures that take in information from many different brain regions, some are intermediate structures that help interpret this incoming information according to pre-learned behavioral relevance (e.g., linking a specific place to a negative past experience), and finally, there are output structures that control our physiological responses to that input information via the hypothalamus.”

“We saw that the social cognitive network potentially includes regions in each of these three levels: input, intermediate, and output. The output structure was really interesting because the main output nucleus of the amygdala is the central nucleus, however, we saw a connection between the social cognitive network and the other, less studied, output structure: the medial nucleus. This was surprising, and as we dove into the literature, we realized that there is a lot of past work linking the medial nucleus to the control of social behaviors. That really helped us make sense of the connections we were seeing: it makes a lot of sense that the regions we use to think about other people have this specific link to the medial nucleus that helps us navigate social interactions!”

To build further confidence in their results, the team compared findings across the two datasets—the one with many sessions per person and the other with several scanning sessions—and even looked at data from more than 4,000 participants in a separate large-scale study. In every case, the same pattern emerged: the brain network that helps us understand others is connected with deep, evolutionarily older regions of the brain, including parts of the amygdala and nearby areas that process emotions.

“The connection between the amygdala and the rest of the social cognitive network is important in the context of treatments for psychiatric conditions, as abnormal amygdala function is thought to underlie anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders,” the researchers told PsyPost. “Knowledge of this amygdala connection suggests that administering stimulation to the regions of the social cognitive network could indirectly modulate activity in the amygdala. This is worth investigating, especially as it is easier to target stimulation to the larger, social cognitive network than the amygdala which is small and deep within the brain.”

The study provides robust evidence for a link between the social cognition network and the amygdala, but there are some limitations to consider. The primary dataset used in the study, while providing high-quality, high-resolution data, included a relatively small number of participants (six). This is a common constraint in studies that require extensive scanning of each individual. The study was strengthened by the inclusion of a second dataset with eight participants, and further validated with an extremely large sample of thousands of participants.

Future research could explore the dynamics of this amygdala-network connection during different types of social tasks. It would also be valuable to investigate how this connection develops over time and how it might be altered in individuals with social cognitive impairments, such as those with autism or schizophrenia. Understanding these connections in greater detail could ultimately lead to new interventions and treatments for conditions that affect social functioning.

“One of our long-term goals is to look for connections between the amygdala and other brain networks outside of the social cognitive network,” Braga and Edmonds said. “In this paper, we report a connection between the social cognitive network and specific portions of the amygdala, but an open question is what other networks are connected to the amygdala, and what do the details of these connections tell us about the function of each network?”

The study, “The human social cognitive network contains multiple regions within the amygdala,” was authored by Donnisa Edmonds, Joseph J. Salvo, Nathan Anderson, Maya Lakshman, Qiaohan Yang, Kendrick Kay, Christina Zelano, and Rodrigo M. Braga.