Abstract

In the context of media studies, the theme of populism in its relation to digital media has gained a great prominence in the last decade. The emergence of new populist political actors that use direct communication to appeal to the people without intermediaries, as well as the consolidation of digital social networks, involve interfaces between media and political processes that we intend to observe, having as object the scenario of the Portuguese Legislative Elections of 2022. Indeed, in this article we address how the populist communication of André Ventura, leader of the Portuguese radical right party, Chega, is constructed during the election campaign period. To analyze the discursive mechanisms of populism in the digital realm, we conducted a study of the corpus derived from André Ventura’s posts on the social media platform X, previously known as Twitter, during the month of January 2022, coinciding with the electoral campaign period. We sought to describe the discursive strategies present in the construction of the representation of “people”, considering the polarization “us versus them”, and examine the meanings of the world mobilized by populist communication in opposition to out-groups identified as “enemies” of the pure or authentic people. The results of our content analysis, focusing on the 143 tweets constituting Ventura’s narrative during the election period, indicate parallels with the discursive tactics of radical right populism. These include a narrative emphasizing conflict between “us and them,” a spotlight on the dysfunctions within the democratic system, the glorification of integrity in the face of political corruption, nativist discourse, and a prevailing tendency towards negative communication.

Introduction

Populism has been defined in various ways, primarily in relation to political ideology, but in recent years, it has also been examined in terms of communication variables, particularly focusing on the style of populist leaders and the discursive dynamics that enable the construction of populist communication. The aim of this paper is to contribute to the identification of populist communication in the Portuguese context, profoundly influenced by the specific nature of social media. Indeed, the contemporary “populist zeitgeist” (Mudde, 2004: p 1) is largely attributed to protest politics and the increased use of digital social media in contemporary political communication. By providing a direct interaction with the citizenry, as compared to the mediated communication of traditional media, political actors are able to shape the public agenda through a process of “informational self-mediation” (Cammaerts, 2012), communicational aspects particularly exploited by populist leaders, as bibliography has sought to demonstrate (Krämer, 2017; Gerbaudo, 2018; Mazzoleni and Bracciale, 2018; Prior, 2021). Particularly in Europe, the radical right populist parties have increased their voter base, breaking into many parliaments.

As academic literature has duly pointed out (Laclau, 2005; Taggart, 2004; Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017), populism transcends the right-left axis, and is, therefore, not synonymous with far-right or right-wing radicalism seeking sovereignty. In Europe, we see left-wing parties like Syriza and Podemos sharing themes and rhetoric (such as anti-elitism) with parties at the other end of the political/populist spectrum, even though they start from a different ideological perspective (Mazzoleni and Bracciale, 2018). In Latin America, for example, populism has historically been associated with the left and an economic vision centered on income redistribution. Therefore, in this article, we aim to explore the populist communication of André Ventura, the leader of the Portuguese party Chega, a radical right party founded in 2019, highlighting elements of populist rhetoric employed in appeals to the people.

According to Jagers and Walgrave (2007), populism can be conceived as a political style that emphasizes proximity to the people while adopting an anti-system and anti-elite discourse, highlighting the homogeneity of the people and excluding specific population segments. In the specific case of radical right populist movements, these segments often include ethnic or religious minorities and immigrants (Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017; de Vreese et al. 2018). Thus, the focus is on the populist leader’s messages and the linguistic stratagems that help construct ideas or political projects that appeal to the people in defiance of the elites or the political establishment. Authors such as Jagers and Walgrave, when considering populism from a communication approach, identify levels or degrees of populism in the communication of political leaders, such as “complete populism”, “exclusive populism”, “anti-elitist populism” and “empty populism”.

“Complete populism” includes reference and appeals to the people, anti-elitism, and exclusion of out-groups. “Excluding populism” includes only references and appeals to the people and exclusion of out-groups, whereas “anti-elitist populism” includes reference and appeals to the people and anti-elitism. Finally, “empty populism” includes only reference and appeals to the people (Alberg et al. 2017; Jagers and Walgrave, 2007; de Vreese et al. 2018).

In Portugal, Chega party, led by André Ventura, went from seventh to third political force in the 2022 elections, obtaining about 400,000 votes, corresponding to 7.18 percent, a result that earned the party the election of 12 deputies to the Portuguese hemicycle. Chega party, founded by André Ventura, has emerged as a notable political force in Portugal in recent years. Established in 2019, this party quickly made its mark on the Portuguese political scene, promoting a platform of radical right politics with populist elements. André Ventura, the party’s leader, is a charismatic and controversial figure who played a significant role in the creation and rise of Chega. Before founding the party, Ventura was a member of the Social Democratic Party (PSD), the largest center-right party, and a city councilor in Loures. Prior to entering politics, André Ventura was a university professor and a sports commentator on CMTV, the largest cable television channel. His sports commentary on television earned him significant media visibility.

Chega party has often been labeled as a radical right populist party due to its policies and rhetoric. It advocates an anti-immigration stance, with a particular emphasis on reducing illegal immigration and strengthening border security. It is also critical of the European Union, calling for greater national sovereignty. André Ventura employs a rhetoric that directly appeals to the concerns and discontent of a portion of the Portuguese population, often using communication strategies that polarize public opinion. This populist and confrontational approach has garnered support, particularly among voters dissatisfied with the political and economic establishment. Similar to its European counterparts, Chega’s populism is rooted in a discursive strategy based on legalistic, security-focused, and anti-elite slogans. Through this discursive strategy, Chega aims to differentiate itself from other political actors, especially those on the right, capture constant media attention, and provide an easily understandable alternative to the diffuse sentiment of anti-politics (Marchi, 2020: p 215). Chega party belongs to the so-called ‘new’ radical right party family. Unlike the ‘old’ extreme-right parties these parties do not refer to the fascist tradition nor do they directly challenge democracy. New contemporary radicalism parties focus on immigrant and law and order themes in a populist and antipolitical discourse (Ignazi, 1992).

Radical right and populist communication strategies

In fact, “populism” has become one of the main terms in the political and media debate of the 21st century, exerting great attraction on politicians, journalists, and academics. Populism is a contested concept essentially because of two criticisms leveled at the phenomenon. First, that it is primarily a “fighting term” (Kampfbegriff) to disqualify political opponents. Second, that the term is vague and imprecise and therefore can apply to all political figures.

In media and political studies, the academic literature has situated populism as an ideology (Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017), logic/discourse (Laclau, 2005), and political strategy of mobilization (Jansen, 2011; Weyland, 2021). The different meanings prove, in a way, the malleability and porosity of populism, since it presents itself, in the field of ideas, as an authoritarian political vision adapted to a democratic context, in the field of discourse, as a rhetoric of polarization between the people and the dominant elites, and, in the field of strategy, as a capacity of mobilization and articulation of the voters most dissatisfied with the political establishment.

Many researchers have emphasized the discursive dimension of populism, focusing their analysis on the communication style of populist leaders and their linguistic strategies (Canovan, 1999; Bos, van der Brug and de Vreese, 2011; Krämer, 2014; 2017). This understanding of populism tends to highlight how ideas are conveyed and the discourse is performative through a certain stylistic repertoire that appeals to the friend-enemy polarization, the “us versus them” antagonism. Among the rhetorical strategies used, notable elements include the simplification of political conflicts, the use of moral appeals, discursive negativity, and the vulgarity and crudeness of rhetorical techniques employed. In a study on the 2018 Italian elections, Martella and Bracciale (2022) concluded that negative emotions are associated with populist leaders, especially on social media platforms. This is a strategy to gain visibility on social networks, as it triggers interactions and reactions from followers.

If we look at the most recent chapter in the history of populism, we see the emergence of a myriad of political parties and movements emerging on the more radical bangs of the right-wing spectrum. The “age of Trump,” as the former White House tenant referred to our time, attests to the global nature of right-wing populism. These are political figures who claim to want to put the native people “above everything else” and who make up a new right-wing extremist international that seeks to impose the “illiberal tradition” by democratic means.

Now, populism is a form of direct democracy sustained by a leader who, without the mediation of traditional institutions, seeks to homologate his political actions with the voice of the “people”. The fundamental premise of populism is therefore the idea of unifying the leader to the people (Finchelstein, 2020), an idea that starts from a democratic premise, but which has historically had authoritarian, illiberal, and anti-pluralist implications. Mudde and Kaltwasser (2017), Muller (2017), or Pappas (2017) are some of the authors who consider populism to be a threat to liberal democracy, precisely because it presents itself as the opposite of pluralism in politics. Successful populists manage to construct the concept of “people”, which they claim to embody, in moral opposition to elites and certain minority groups interpreted as a threat (out-groups).

Populist discourse thus polarizes society between “us and them,” the people and their enemies, whether political, economic, cultural elites, or minority groups that are blamed for problems in society, always in a logic of conflict between “good and evil,” “us versus them.” Consequently, populism discursively articulates an antagonistic view of politics, mobilizing the “people” against the established powers, emphasizing the authority of the vox populi against those in power who are invariably described as corrupt or traitors to the people’s trust, and stigmatizing minority social groups, often with a xenophobic, misogynistic, or homophobic discourse. In effect, populism is opposed to pluralism in politics, since the populist leader speaks on behalf of an imaginary majority, the people, denying, often in moral terms, all the demands he considers part of the minority. In their right-wing version, the enemies of the people invariably include ethnic and religious minorities, as does the independent press. Jean-Marie Le Pen, Marine Le Pen, Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro and other far-right leaders present themselves as the antithesis of the corrupt elites, conceiving their role in messianic terms. They underline their contrast with the elites and traditional politics, instigating anti-politics sentiments, that is, hatred for politics, the parties of the so-called establishment, and the very institutions of check and balances that characterize liberal democracy. In Europe, the slogan “Stop Immigration”, used by British National Front (NF) in the 1980s, an extreme right party with a fascist genesis, is part of the discursive repertoire of radical right parties such as Vox, AfD, or La Lega.

Indeed, for an author such as Cas Mudde (2016), today we are living a wave of institutionalization of right-wing populism, mainstreaming of the far right, that is, a moment in which far right and radical right parties have representation in national parliaments and the European Parliament and are even part of governing coalitions in several countries. Populist radical right can be defined as parties that are anti-establishment and hostile to some elements that shape liberal democracy, such as the tripartite division of powers, the safeguarding of minority rights, or freedom of the press. It is also useful to understand right-wing populisms is the distinction between right-wing extremism and right-wing radicalism theorized by German constitutional jurisprudence. That is, while the extreme right rejects the rules of democracy, such as popular sovereignty and majority power, and is in favor of killing the regime by violent or subversive means, the radical right accepts the rules of democracy, although it opposes some of its basic principles, such as human rights or respect for minorities. This distinction is relevant because it determines the legality of right-wing radicalism, which seeks substantial regime change through democratic means, respecting the rules of the game and elections, and the illegality of right-wing extremism, which seeks regime replacement through illegal and even violent means (Mudde, 2016; Marchi, 2020). In fact, the scientific debate about populism has been revitalized by the recent rise of extreme and radical right parties in Western Europe (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007). Faced with political and social changes in Europe driven by European integration and immigration-related issues, radical right populist parties have emerged in response to perceived frustrations. These parties, characterized by their amalgamation of populism, authoritarianism, and nativism, reflect concerns about social order and the preservation of national identity amidst perceived challenges.

For the populist radical right, the conflict between natives and non-natives is primarily viewed as a political matter, leading them to confront their opponents within the framework of democracy. These groups are characterized as illiberal democrats, as explained earlier. On the other hand, extreme right groups are those that outright reject the constitutional order and seek to undermine the democratic status quo. For them, the struggle between natives and non-natives is seen as a fundamental issue; they are willing to escalate the conflict beyond the political sphere and eliminate their adversaries. They enter the political arena with the aim of destruction and follow a radically different approach. Therefore, the extreme right is fundamentally opposed to democratic principles (Pirro, 2021: pp 105–106).

Observations on populism in the digital sphere

There is an assumption, widely accepted by the academic community and evident in several recent electoral processes, particularly since Barack Obama’s initial election in 2008, that digital social networks have served as influential and legitimized channels of political communication. They contribute to the imposition of cultural and historical narratives and the construction of signification regimes that influence social dynamics. These regimes are characterized by fluidity and permeability.

With digital media, political actors become autonomous in the production and dissemination of their messages, avoiding traditional media and their mediation and filtering. Citizens themselves are stripped of the passivity that used to define their role in the traditional political communication process. In effect, there is an “empowerment” of political and social actors in an ecosystem characterized by more fluid, fragmented and hybrid communication flows in which traditional and new media shape power relations.

Social networks have become an especially useful mechanism for political and social actors who challenge political and media elites, since the Internet offers communicative autonomy that allows them to produce and disseminate their messages without the mediation of traditional gatekeepers (Engesser et al. 2017). In this context, populist politicians, who challenge the elites and the establishment, have found in the digital environment a space that allows them to directly contact their followers, challenge the political system, and acquire informational potential, since through the Internet they increase the possibilities of giving visibility to their messages, taking advantage of the new discursive opportunity structures of the public sphere. Otherwise, populists also emphasize the democratizing potential of the Internet, invoking free speech to attack their opponents, stigmatize out-groups of the population that they consider a threat to the pure or native people, and instigate citizen outrage at a political system constantly described as “corrupt”, often through crude discourse that defies political correctness and serves to create an emotional bond with the average citizen.

The horizontality and ubiquity of social media allow a vast circulation of populist content with high potential impact. This phenomenon is further exacerbated by the homophily of the Internet, characterized by the presence of a “filter bubble” that selectively presents like-minded media content, as noted by Engesser et al. (2017). According to Mazzoleni and Bracciale, “in the specific case of socially mediated populist communication, the network media logic means that populist leaders’ linkage with their constituencies or sympathizers is entirely disintermediated: that is, the production of contents is free from being filtered by journalists or other types of gatekeepers” (Mazzoleni and Bracciale, 2018: p 3).

Under the pretext of direct democracy, they take advantage of the bidirectionality of the social networks to promote direct representation and assume themselves as an extension of the people in the defense of their interests against selfish elites, only interested in their own designs. In short, the possibility to appeal directly to the people without intermediaries, to criticize the establishment, and to spread information through alternative channels to the mainstream media, make social networks the ideal ecosystem for the production and circulation of populist leaders’ messages. Its repercussion in the political world is so evident, that around 92 percent of world leaders have a X (formerly Twitter) profile (Burson 2023), converting this communication tool into an important tool within election campaigns.

The disintermediation processes that characterize the hybrid media system (Chadwick, 2013) allows politicians and parties to spread their issues with favorable framings, as well as their programmatic proposals, in a communicative process of self-mediation, corresponding to the individual mass communication theorized by Castells (2009). It is also a social network used to publicize the official campaign channels, such as the web pages, share political statements and information about the candidates’ agenda, and mobilize the electorate by appealing to vote and donate economic resources (Van-Kessel and Castelein, 2016; Alonso Muñoz and Casero-Rippollés, 2018; Amaral, 2020).

Indeed, in the context of post-digital societies, political discourses operate in a model of communicability marked by new sociolinguistic conditions of production, circulation and absorption of discourses, new resources, new actors and new relations between actors, as Blommaert (2020) points out. Post-digital environments are new environments permeated by sociolinguistic conditions that affect contemporary discourses, such as the intermingling of online and offline, discursive circulation oriented to niche but highly capillary audiences, the hybridization of media systems, and the impact of high technology in an algorithm-driven ecosystem. This is the case with the social network Twitter, a network with microblogging characteristics, ideal for stimulating political personalization. The relationships between Twitter users are not reciprocal, that is, it is possible to read a person’s posts without being his follower, and they are relationships guided by technology and artificial intelligence in a model of mediation that is distinct from the old logics of political propaganda underlying the linear model of mass communication. In the old logic of political propaganda, the messages produced by political actors are transmitted and inculcated into the public by mass media, public or private, that share the same corporate interests as the powerful elites. In such models, the mass media function as catalysts for the interests of these groups, ensuring “propaganda effects” on public opinion (Blommaert, 2020).

A Twitter post produced by someone (for example, André Ventura of Chega party), is sent to a non-human receiver – an algorithm – through which artificial intelligence operations transmit it to numerous specific audiences, whose responses are transmitted, as data, to the algorithm and from there to the sender of the tweet in uninterrupted sequences of indirect, technology-mediated interaction. This audience can transmit the tweet or the interpretation of that message to secondary audiences, allowing a message to reach audiences that were not initially accessible. This means that audiences, often called digital bubbles, are built either by followers or by algorithms from users’ data on the web, data gathered through thematic keywords such as hashtags, interaction history, and digital footprints. In the case of accounts or profiles with high standards and engagement, this process tends to be intensified not only by voters, but also by bots – accounts that are programmed to behave like ordinary individuals and generate specific ways of responding to messages that exponentially increase their traffic volume.

On the other hand, in processes such as the massive distribution and replication of messages in online networks, there is a process of decontextualization/recontextualization of discourses that affect the modes of signification of texts that circulate in multiple and incessant trajectories. The notions of discourse mobility and textualization have been used to understand the process of online communication in social networks like Twitter, where each tweet and retweet instigates new interpretations and recontextualizations. The circulation of texts and signs in a polycentric and multidimensional trajectory associates historical, cultural, and political meanings and has, therefore, an important metalinguistic dimension for the understanding of political discourses in online signification practices (Silva, 2020).

In summary, aspects such as: (1) the individualized form of populist communication through social media, (2) its popularity-driven inclination, (3) its disintermediated nature, (4) its encouragement of like-minded communities should be regarded as significant indicators of a distinctive process of mediatization of political communication (Mazzoleni and Bracciale, 2018: p 3). In this sense, Gerbaudo uses the term “populism 2.0” to refer to an elective affinity between social media and populism (Gerbaudo, 2018). According to Gerbaudo, social media provides a suitable channel for the typical appeals of populism, especially through anti-system rhetoric, allowing dissatisfied individuals to express their discontent with the status quo. These individuals can, through the Internet, form online partisan groups that foster a libertarian narrative towards the traditional political system. It is what authors such as Ernst et al. (2018) refer to as “favorable opportunity structures” for populist communication.

Methodology and research design

One of the central objectives of this research is to understand the use that the leader of the main Portuguese populist party makes of X, formerly Twitter, as well as his thematic agenda and the main discursive strategies mobilized. More specifically, our aim with this research is:

O1) “to identify the thematic agenda of the leader of the main Portuguese populist party, André Ventura;”

O2) “to deconstruct the argumentative strategies present in the construction of the representation of ‘people’, considering the polarization ‘us versus them’, and, at the same time, problematize the meanings of the world mobilized by populist communication in opposition to out-groups identified as ‘enemies’ of the pure people, or ‘good Portuguese’.”

To understand the issues in dispute, we pose the following research questions:

RQ1. What topics are present in André Ventura’s agenda on his official Twitter account during the election campaign period?

RQ2. What elements of populist communication does the candidate mobilize during the analyzed period?

RQ3. What are the different degrees of populism in the rhetoric used by André Ventura on X social media?

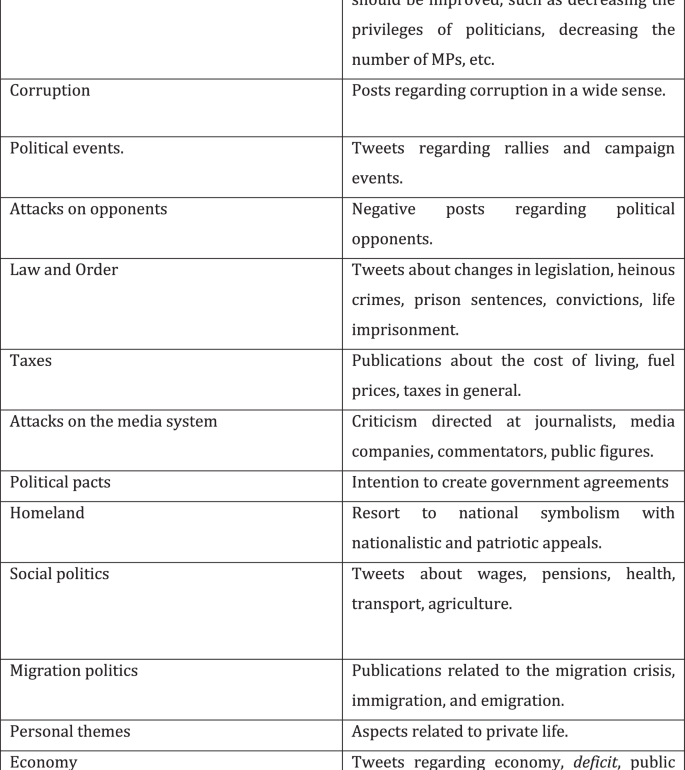

To answer the objectives and research questions, the content analysis technique is used, which allows capturing the structure and components that form the messages (Bardin, 2018), extracting, through a critical qualitative reading, some inferences about populist communication. Our sample consists of 143 messages posted on André Ventura’s Twitter profile between January 3 and 29, 2022, the month of the 2022 Legislative Elections. As an analysis protocol, thirteen exhaustive and unique categories were constructed for the study of the thematic agenda. Once the substantive points of the discourse have been identified and classified, we seek to uncover meanings that lie in the background. Figure 1 presents the analysis protocol set up.

Results‘ discussion

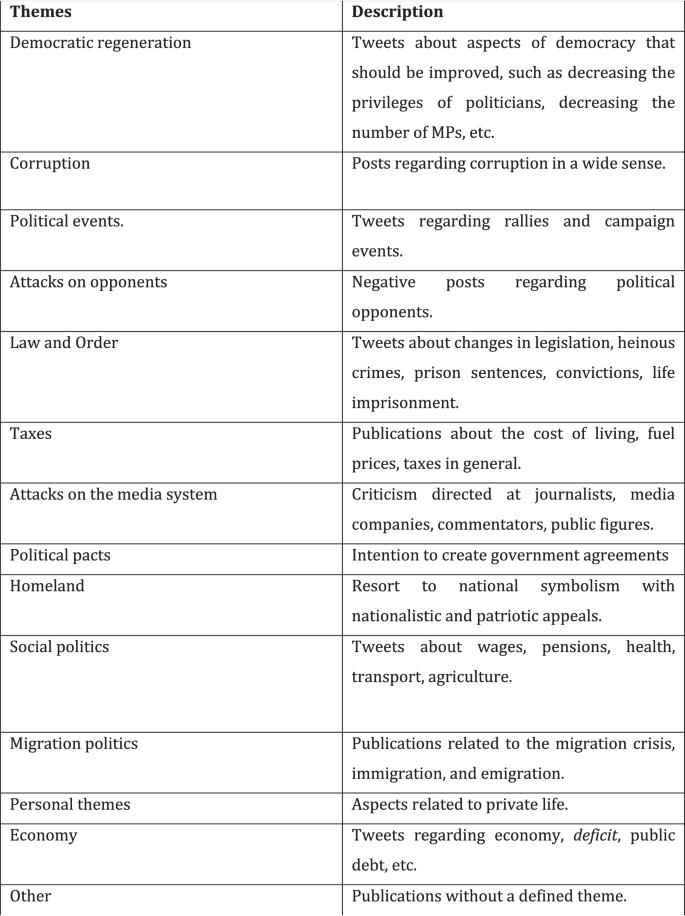

Given the relevance of the social network X, formerly known as Twitter, in election campaigns, it’s not surprising that André Ventura has a very active account. The leader of Chega’s page has over 144 thousand followers, much more than Luís Montenegro’s network, who at the time was the leader of the largest opposition party, the PSD, which has just a little over 16 thousand followers. However, both are far behind the number of followers of the now former Prime Minister, António Costa, who has 312,482 followers.Footnote 1 The analysis of the thematic agenda supported by populist leaders on Twitter allows us to identify several interesting empirical evidence. André Ventura has a very compact agenda, in which only two topics, “democratic regeneration” and “corruption”, account for 39.1% of his messages Fig. 2.

Democratic regeneration (21%) is André Ventura’s preferred theme. He advocates for regenerating democracy by implementing actions that eliminate privileges held by political elites. This rhetoric is especially common among the recent populist parties, which present themselves as “the new” against “old politics,” demanding a profound democratic regeneration to alleviate the negative effects of the crisis of representative democracy, and to eliminate the existing vices of the traditional party system. For André Ventura, Chega party bothers the establishment because it questions the status quo, described as “corrupt and corrupting”.

In fact, André Ventura focuses his communication strategy on criticizing corruption cases (18.1%), associating the government leader, António Costa, with the corruption scandal allegedly involving the former socialist prime minister, José Sócrates. The Socialist Party and its members are the primary targets of Ventura’s scrutiny, with the politician delving deeply into their actions. Ventura highlights the connection between José Sócrates, who is accused of corruption and tax fraud in the Marquês Operation, and the government leader. He associates the high taxes paid by the Portuguese people with “socialist corruption”.

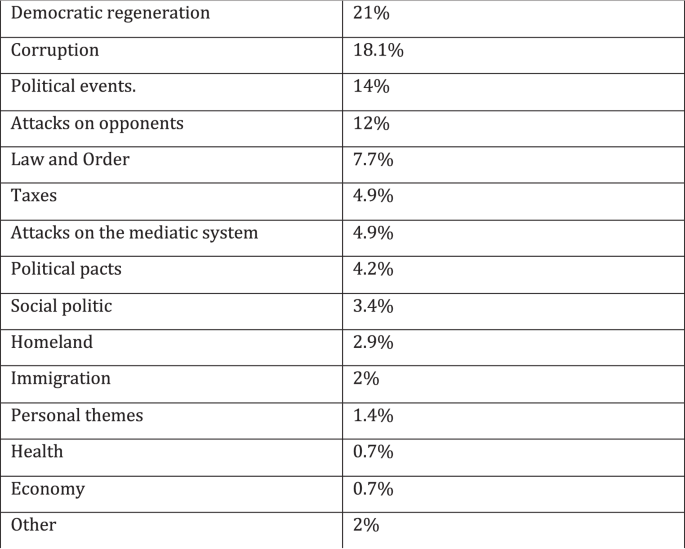

In his Twitter posts, the leader of Chega aims to present himself as the legitimate representative of the “common people,” the real people, against the corrupt elites who for decades have pursued partial interests to the detriment of the general interest. As Eatwell & Goodwin stress, “populists promise to defend simple, ordinary people, always presenting distant elites as enemies, but also attacking others, such as immigrants” (2019, p. 69). His speech explores anti-elitism, associating the traditional political system with the idea of corruption. It is about instigating his followers against the structures of power, speaking on behalf of the people, and seeking to build legitimacy in the name of the democratic sovereign. As highlighted by Jagers and Walgrave (2007), anti-elitist or anti-establishment discourse emphasizes the distance and division between the people and the elites Figs. 3–9.

Publication by André Ventura in which he associates the Prime Minister, António Costa, with José Sócrates, former prime minister involved in several corruption scandals. For André Ventura, voting for Chega party is voting against corruptionFootnote

“Discover the differences! And vote for Chega to end this once and for all.”

.

Post in which André Ventura states that his party represents the ‘common people,’ in line with the ideas and interests of the people, opposing ‘those who have been stealing from the country for decades. Example of the discourse built against the dominant political elitesFootnote

“Being a party of ordinary people is an immense source of pride for us because it means we have the right people by our side: those who work and not those who have been robbing the country for decades.”

.

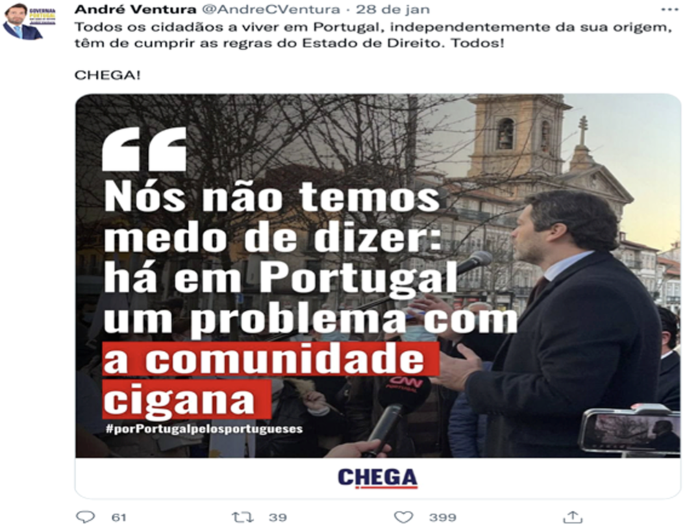

Since 2017, when he was a candidate for Loures City Council for the Social Democratic Party (PSD), André Ventura has made the Roma community the main “threat” of Portuguese society. This community is often accused by the politician of living on the margins of society and at the expense of state subsidiesFootnote

“All citizens living in Portugal, regardless of their origin, must abide by the rules of the rule of law. Everyone!”

.

André Ventura speaks near the Guimarães Castle, Portugal’s birthplace. The chosen location is far from coincidence, as radical right-wing populism explores aspects related to national identityFootnote

“Some prefer to continue granting subsidies to criminals and those who refuse to work! In the CHEGA, we prefer to dignify our security forces!”

.

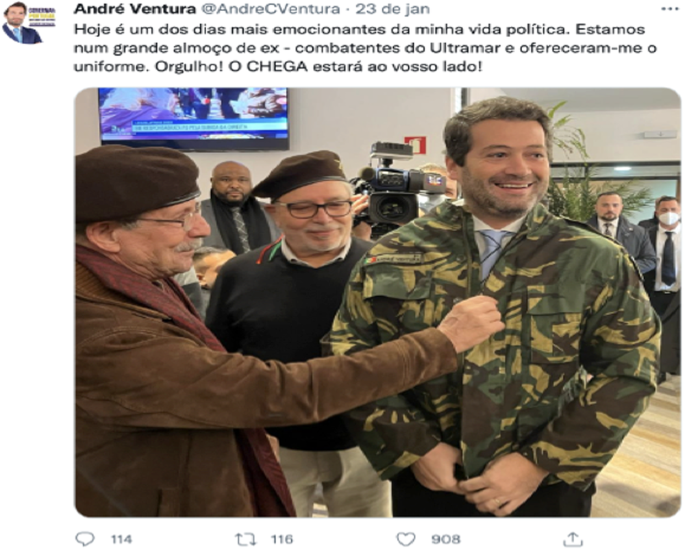

In the name of “tradition” and of the ex-combatants in the Overseas War, André Ventura wore the military camouflage and promised a monthly subsidy of at least 200 euros for those who defended the interests of the countryFootnote

“Today is one of the most exciting days of my political life. We are at a great lunch with former overseas combatants and they offered me the uniform. Pride! CHEGA will be by your side!”

.

Besides the anti-establishment discourse, characteristic of populist rhetoric, it is relevant to underline the emphasis given to issues that refer to the Portuguese population’s feeling of insecurity, with emphasis on crimes committed against the police, especially by minorities, such as the black population and the Roma community. The references regarding these questions serve a critical function. André Ventura advocates increased policing around universities, schools, and nightlife venues to protect the “good Portuguese” from the criminality and delinquency that, in his view, affects the country. Life imprisonment is one of the measures André Ventura insists on the most. These references, included in the “Law and Order” category, occupy 7.7% of the total publications and are very common in the new populist parties of the radical right. His discourse is based on an “inclusion-exclusion” dynamic regarding immigration and, above all, to the gypsy community, alluding to the fact that improvements are promoted for the “good Portuguese” and not for these groups, excluded from this category. André Ventura constructs the Roma community as the main out-group of his political rhetoric, claiming that it is a community that lives on the margins of the law and at the expense of political subsidies from the state. Marriage to and between persons under the age of 18 is one of the issues highlighted by the candidate. Gypsies are seen as the main internal enemy to fight.

In relation to immigration and terrorism, the criticism focuses particularly on the Muslim population that is accused of “not wanting to integrate into European society” and is associated with illegality and terrorism. The politician accuses immigrants, especially the Muslim community, of wanting to change the “way of life” of native Europeans. André Ventura also shares news of crimes involving immigrants, accentuating the feeling of insecurity caused by this community. As it turns out, the notion of exclusion activated by populist leaders refers not only to the “elite,” but also to other groups excluded from the “people,” usually for ethnic, religious, sexual, or economic reasons, such as immigrants or ethnic and/or religious minorities (Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017; Jagers and Walgrave, 2007). The exclusion of these groups has sustained a rhetoric based on an anti-immigration discourse and the rejection of minorities, especially among populist politicians on the radical right spectrum (Taggart, 2000).

André Ventura also insists on the idea that Chega is persecuted and ostracized by the mainstream media because of the policies he advocates. He devotes several publications to criticizing commentators, comedians, and journalists, including the media in the corrupt establishment. Ventura condemns the servility that some media maintain towards political and economic elites. Criticism of the media or media personalities occupies 4.9% of the messages posted by André Ventura on Twitter, confirming the difficulty of the relationship of populist leaders with the traditional media.

As Paul Taggart (2000) points out, populisms strive to demonstrate that society is in crisis, collapsing, or under threat. The aim is to simplify social and political reality to radicalize and polarize the debate as much as possible. The economic crisis has acted as a strong driver of recent populist phenomena, helping their consolidation and growth. The economic crisis has capitalized on the attention of these actors in recent years, placing the financial system, capitalism, and austerity generated by technocrats at the center of their criticism (Moffitt and Tormey, 2014). In their ongoing struggle against corrupt “elites,” they focus their discourse on economic issues and on the social, migratory and representational difficulties that our societies face. Themes that instigate the narrative of social and economic crisis are explored in André Ventura’s publications, which criticize the value of pensions and salaries, as well as the price of energy and fuel, always linking these problems to political corruption.

In this sense, populist messages tend to evoke discursive negativity, portraying a state of crisis of the institutions: “Crises are often related to disruption between citizens and their representatives, but may also be related to immigration, economic hardship, perceived injustice, military threat, social change, or other issues”(Moffitt and Tormey, 2014: p 392).

André Ventura also tries to exacerbate nationalist feelings by exalting symbolic elements of the nation and patriotic feelings, underlining a certain impressive and nostalgic past that should be recovered. The nationalistic framing of the messages refers to a populism that emphasizes national traditions, history, language, and culture. Nationalism is closely related to the idea of “heartland” or “motherland” as a central dimension of populism (Taggart, 2000). During the campaign, Ventura organized a series of events at historical monuments in Portugal, such as the Batalha Monastery, also known as the “homeland monument”, or the Guimarães Castle, Portugal’s birthplace.

During the election campaign, the leader of Chega also participated in meetings with former soldiers of the Overseas War, appealing to the patriotic and nationalistic feelings of the Portuguese people and promising not to abandon those who, in the past, defended the nation’s values. The candidate promised a monthly subsidy for war combatants in Africa, condemned by successive governments to “misery” and “oblivion.”

In defense of the values of the homeland and of the “good Portuguese”, Ventura presents himself as a messianic candidate, claiming that he has a divine mission to save the country. Ventura’s messianism is illustrated by a publication alongside the leader of the Spanish Vox party, Santiago Abascal, stressing that both “have the mission to save the Iberian Peninsula from socialism.” Messianic candidates are one of the essences of populism. The messianic discourse is used as an element of legitimization of the populist actor who presents himself as an identity representative of the people, an unpolluted being or a “divine blessing.” The idea of political messianism is linked to religious messianism and consists of the belief in the arrival of a great leader who will free the people from oppression and injustice. According to Zúquete (2013) political messianism or “Missionary Politics” is a political religion that has at its center charismatic leadership, a salvation narrative, ritualization, and the creation of a moral community invested with a collective mission to combat conspiratorial enemies and redeem the community from its purported crisis. Just as religions often have salvation narratives, political messianism also constructs a narrative that describes a state of crisis or societal decay. This narrative is used to convince people that a radical transformation is necessary to save the community or nation. It focuses on mobilizing followers around a messianic political vision and often involves a struggle against perceived enemies. André Ventura’s messianism aims to create an online community of followers who share moral principles used for populist political action, a radical transformation aimed at purifying the political system. The messianic dimension of Ventura’s discourse is highlighted by Dias, for whom “the strong religious dimension of Portuguese society, spanning from the ecclesiastical framework to popular Catholicism, allows for a political appropriation that reinforces the figure of the political messiah” (Dias, 2020: p 56), who will lead his people, “the good people,” towards a new nation free from corruption and the impious. In his study on political messianism, Dias demonstrated that the leader of Chega navigates the waters of Portuguese colonial memory with a narrative of a country devoid of racism and political messianism rooted in Sebastianism in the case of Portugal, representing a poetic-prophetic aspiration for the return of the political savior. To acquire a religious aura, Ventura employs elements of popular Portuguese religiosity, such as the Miracle of Fatima (Dias, 2022).

Conclusions

The results obtained and discussed here allow us to identify some contributions regarding the construction of the agenda on Twitter by the most prominent populist leader on the Portuguese scene. First, although social media, particularly the Twitter platform, encourage self-mediation processes, this is not reflected in a high fragmentation of the political agenda. André Ventura presents a very compact agenda concentrated around two issues, “democratic regeneration” and “corruption”. Secondly, one notes a preoccupation with issues related to immigration and security, issues common to European parties of the radical right. These themes are emphasized in terms of the “inclusion-exclusion” of social groups, fomenting polarization between “us and them”, “the good Portuguese” and the Roma and Muslim community, negatively qualified and accused of remaining on the margins of social norms and the rule of law. Immigrants are also explicitly connoted with the increase of terrorism and insecurity in the country, a strategy visible in the communication of conservative populist leaders (Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripollés, 2018: p 1199). Issues related to justice, particularly the tightening of legislation and penalties for heinous crimes, are also emphasized in the communication from the leader of Chega. Indeed, André Ventura’s communication is in line with the ideological characteristics of the European radical right, namely nativism, populism, and authoritarianism (Mendes, 2021).

Through the tweets posted on André Ventura’s official page, we conclude that this political actor promotes a populist communication with a strong emotional basis and an anti-system discourse. André Ventura’s publications confirm the populist trend, conveying an “aggressive” discourse against the dominant political system. According to Ostiguy, “expressive anger is one of the pillars of the populist communication style. Includes the dimensions of emotion and negativity. This violent discourse is used as a strategy, seeking to demonstrate that the status quo is not acceptable” (2017, p 7).

Criticism of the government and public figures is very frequent, following the strategy of negative personalization, with criticism of political opponents predominating in moralistic tones. Nationalism and nativism are exacerbated in the tweets that generate the most engagement from followers, which shows that these themes tap into emotion with their followers. Simplicity is also a common feature present in populist message. These dimensions are found in virtually all populist leaders who promote a familiar, colloquial, and sometimes vulgar discourse (Canovan, 1999).

One of the features of populist political rationality that is shown to be common in Ventura’s discourse concerns the mobilization of what Laclau (2005) has named “floating signifiers.” Words and images that, not possessing a stable or transparent content of signification, are systematically summoned without the need to delimit their meaning. The dispute over such signifiers is mobilized through media campaigns driven by hashtags and slogans, such as #porPortugal, #pelosportugueses. Signifiers whose meanings are in suspense, such as “justice,” “criminality,” “corruption,” are appropriated by populist discourse and placed at the center of the political project. They allow the “chain of equivalences” (Laclau, 2005) of groups involved in social justice, fighting crime, and defending “public morality” to be erected, linking the leader to the “people”.

Our results suggest that all three defining aspects of complete populism are present in the communication of André Ventura. This political actor appeals to the people and also attacks the establishment and excludes groups, particularly immigrants and the Roma community. The dimension which refers to the rhetorical construction of the ‘dangerous others’, is a typical element of the nationalist and xenophobic right-wing formations (Mazzoleni and Bracciale, 2018: p 8). The dimensions of anti-elitism and exclusionary populism are also present. André Ventura’s anti-elitism is evident in his criticism of political elites, particularly the two major governing political parties, the Socialist Party (PS) and the Social Democratic Party, but also cultural elites and the media system, framed within the corrupt establishment. Regarding exclusionary populism, it is visible in the construction of the “other” as an identity threat to the native people, presenting Muslim immigrants as the ideal out-group. In fact, Muslims have become the ideal out-group in the populist rhetoric of the radical right, making Islamophobic views so central in today’s radical right populist discourse that some scholars have started to use the term “Islamophobic populism” (Hafez 2017). This idea is in line with the perspective of Mudde and Kaltwasser (2017) when they state that, especially after September 11, Islamophobia has become the main populist paradigm of the far right and radical right family parties.

The concept of “complete populism” closely mirrors findings from Jagers and Walgrave (2007) regarding the communication of the Vlaams Blok, as well as insights from Mazzoleni and Bracciale (2018) regarding the Italian case, thus affirming its potential applicability across various national contexts, particularly in the Portuguese context.

The Portuguese case highlights the nuances of socially mediated populist communication, shedding light on its characteristics, degrees, and societal and political implications in contemporary discourse. In the 2024 Legislative Elections, Chega party capitalized on the prevailing environment of crisis, fragmentation, and instability that has characterized Portuguese politics in recent years, asserting itself as the third political force and putting an end to the so-called bipartisanship. The party led by André Ventura obtained over 18% of the votes, managing to elect 50 deputies to the Portuguese parliament. The emergence and consolidation of Chega party allow for the transposition of the discussion on radical right populism proposed by academic debate in recent decades to Portugal. The party led by André Ventura interprets politics as a confrontation between the people and elites, employing an anti-system rhetoric, qualifying foreigners as a threat to internal security through nativist rhetoric, and challenging principles of contemporary liberal democracy to the detriment of minorities and in favor of security-oriented law and order policies. Utilizing social media and alternative media as a privileged arena for direct communication, André Ventura presents himself as a messiah, the spokesperson for the betrayed native people by the elites of the political system.

Data availability

The data presented in the article were collected from the official Twitter account of André Ventura (https://twitter.com/AndreCVentura) during the month of January 2022. A manual extraction and qualitative analysis of each tweet were conducted after the construction of categories of analysis. The publications were categorized based on their themes, and a quantitative content analysis was conducted. Subsequently, the most relevant publications were analyzed qualitatively. The results are presented within the article itself.

Notes

-

The number of followers was registered on 31/01/2024.

-

“When a party disturbs the entire system and challenges all established interests, it’s because we are doing something right.”

-

“Discover the differences! And vote for Chega to end this once and for all.”

-

“Being a party of ordinary people is an immense source of pride for us because it means we have the right people by our side: those who work and not those who have been robbing the country for decades.”

-

“All citizens living in Portugal, regardless of their origin, must abide by the rules of the rule of law. Everyone!”

-

“Some prefer to continue granting subsidies to criminals and those who refuse to work! In the CHEGA, we prefer to dignify our security forces!”

-

“Today is one of the most exciting days of my political life. We are at a great lunch with former overseas combatants and they offered me the uniform. Pride! CHEGA will be by your side!”

-

“Two men, one destiny: to save the Iberian Peninsula from the socialism that has been impoverishing us daily!”

References

-

Aalberg, T, de Vreese, CH (2017) Introduction: Comprehending Populist Political Communication. In: Aalberg T, Esser F, Reineman C, Stromback J, de Vreese CH (eds) Populist Political Communication in Europe. Routledge Research In Communication Studies, Vol. 1, Routledge, pp 3–11

-

Alonso-Muñoz L, Casero-Ripollés A (2018) Communication of European populist leaders on Twitter: agenda setting and the ‘more is less’ effect. El profesional de. la Inf.ón 27(6):1193–1202

-

Amaral, ACDS (2020). A influência das redes sociais na comunicação política dos partidos de direita radical: o caso do Chega, Lisboa: Iscte, (Master’s thesis)

-

Bardin, L (2018) Análise de Conteúdo, Edições 70, Lisboa

-

Blommaert J (2020) O discurso político em sociedades pós-digitais. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada 59(1):390–403

-

Bos L, van der Brug W, de Vreese C (2011) How the media shape perceptions of right wing populist leaders. Political Commun. 28(2):182–206

-

Burson, M (2023) Twiplomacy Study 2017. Twiplomacy, Available via https://goo.gl/Fb32bJ, Accessed 20 March 2023

-

Cammaerts B (2012) Protest logic and the mediation opportunity structure. Eur. J. Commun. 27(2):117–134

-

Canovan M (1999) Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy. Political Stud. 47(1):2–16

-

Castells M (2009) Comunicación y Poder. Alianza Editorial, Madrid

-

Chadwick A (2013) The hybrid media system. Oxford University Press, Oxford

-

de Vreese CH, Esser F, Aalberg T, Reinemann C, Stanyer J (2018) Populism as an Expression of Political Communication Content and Style: A New Perspective. Int. J. Press/Politics 23(4):423–438

-

Dias JF (2020) The Messiah has come and will redeem the “good people” from the corrupt: political messianism and popular legitimacy, the cases of Bolsonaro and André Ventura. Polis 2(2):49–60

-

Dias JF (2022) Political Messianism in Portugal, the Case of André Ventura. Slovenská politologická Rev. 22(1):79–107

-

Eatwell, R, Goodwin, M (2019) Populismo. A revolta contra a democracia liberal, Porto Salvo: Desassossego, Porto Salvo

-

Engesser S, Ernst N, Esser F et al. (2017) Populism and social media: how politicians spread a fragmented ideology. Inf., Commun. Soc. 20(8):1109–1126

-

Ernst N, Esser F, Blassnig S, Engesser S (2018) Favorable Opportunity Structures for Populist Communication: Comparing Different Types of Politicians and Issues in Social Media, Television and the Press. Int. J. Press/Politics 24(2):165–188

-

Finchelstein, F (2020) Para una historia global del populismo: rupturas y continuidades. In: Pinto, AC; Gentile, F (Ed) Populismo: teorias e Casos, Edmeta Editora, Fortaleza, pp 20-31

-

Gerbaudo P (2018) Social Media and Populism: an elective affinity? Media Cult. Soc. 40(5):745–753

-

Hafez F (2017) Debating the 2015 Islam law in Austrian Parliament: Between legal recognition and Islamophobic populism. Discourse Soc. 28:392–412

-

Ignazi P (1992) The silent counter-revolution. Hypotheses on the emergence of extreme right-wing parties in Europe. Eur. J. Political Res. 22:3–34

-

Jagers J, Walgrave S (2007) Populism as political communication style: An empirical study of political parties’ discourse in Belgium. Eur. J. Political Res. 46(3):319–345

-

Jansen RS (2011) Populist Mobilization: a new theoretical approach to populism. Soc. Theory 29(2):75–96

-

Krämer B (2014) Media populism: a conceptual clarification and some theses on its effects. Commun.-tion Theory 24:42–60

-

Krämer B (2017) Populist online practices: the function of the Internet in right-wing populism. Inf. Commun. Soc. 20(9):1293–1309

-

Laclau, E (2005) La Razón Populista, Fondo de Cultura Económica de España, Madrid

-

Marchi, R (2020) O Novo Partido Chega no âmbito da direita portuguesa, In: Pinto, AC; Gentile, F (Ed) Populismo: teorias e Casos, Edmeta editora, Fortaleza, pp 201-219

-

Martella A, Bracciale R (2022) Populism and emotions: Italian political leaders’ communicative strategies to engage Facebook users, Innovation. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 35(1):65–85

-

Mazzoleni G, Bracciale R (2018) Socially mediated populism: the communicative strategies of political leaders on Facebook. Palgrave Commun. 4(50):1–10

-

Mendes MS (2021) ‘Enough’of What? An Analysis of Chega’s Populist Radical Right Agenda. South Eur. Soc. Politics 26(3):329–353

-

Moffitt B, Tormey S (2014) Rethinking Populism: Politics, Mediatisation and Political Style. Political Stud. 62(2):381–397

-

Mudde C, Kaltwasser CR (2017) Populismo: uma Brevíssima Introdução. Gradiva, Lisboa

-

Mudde C (2004) The populist zeitgeist. Gov. Oppos. 39(4):541–563

-

Mudde C (2016) Europe’s populist surge: A long time in the making. Foreign Aff. 95:25–30

-

Muller JW (2017) O que é o Populismo? Texto Editores, Lisboa

-

Pappas T (2017) Os Diferentes adversários da Democracia liberal. J. Democracy em Port.ês. 6(1):18–40

-

Pirro A (2021) Far right: The significance of and umbrella concept. Nations Nationalism 29:101–112

-

Prior H (2021) Digital Populism and disinformation in post-truth times. Commun. Soc. 34(4):49–64

-

Silva, D (2020) Embates semiótico-discursivos em redes digitais bolsonaristas: populismo, negacionismo, ditadura. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada, 59(2)

-

Taggart P (2000) Populism. Open University Press, London

-

Taggart P (2004) Populism and representative politics in contemporary Europe. J. Political Ideol. 9(3):269–288

-

Van-Kessel S, Castelein R (2016) Shifting theblame: Populist politicians’ use of Twitter as a tool of opposition. J. Contemp. Eur. Res. 12(2):594–614

-

Weyland K (2021) Populism as a Political Strategy: An Approach’s Enduring – and Increasing – Advantages. Political Studies 69(2):185–189

-

Zúquete JP (2013) Missionary Politics.A Contribution to the Study of Populism. Relig. Compass 7(7):263–271

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The state of the art on populism and social media, as well as the methodological design and the empirical study, are the sole responsibility of the author of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author(s) declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Prior, H. Social media and the rise of radical right populism in Portugal: the communicative strategies of André Ventura on X in the 2022 elections.

Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 761 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03224-w

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03224-w

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content