Moka Lee’s portraits and still-lifes have an unsettling, voyeuristic feel to them. The reason, in part, is because of the subject matter: her images are plucked from the social media accounts of strangers. “As a painter, I always look for images I would like to paint,” Lee says. “Social media has naturally been the most approachable, convenient and intuitive source for acquiring these images—at least for me.” There is an interesting dichotomy in her work, combining the meticulous, classical tradition of painting with today’s fast-paced, image-obsessed culture of oversharing.

The Gen Z (born in 1996), Korean artist has been receiving a lot of market attention in the past year. Her works were on show at Art Basel, Frieze Seoul and Frieze London in 2024; her auction debut at Phillips in Hong Kong in November saw her work I’m Not Like Me (2020) quadruple its estimate, selling for HK$1.65m (£170,000); and she was chosen for the Artsy Vanguard 2025, which lists “ten exceptional talents poised to become the next great leaders of contemporary art”. You can find Lee’s work in two London exhibitions this month: at Carlos/Ishikawa where she is having her first UK solo show, titled FACE ID (until 15 February), which includes 13 new works and is part of the collaborative gallery event Condo London 2025 (see p31); and in Jason Haam’s group show Karma II at Frieze No.9 Cork Street (until 15 February).

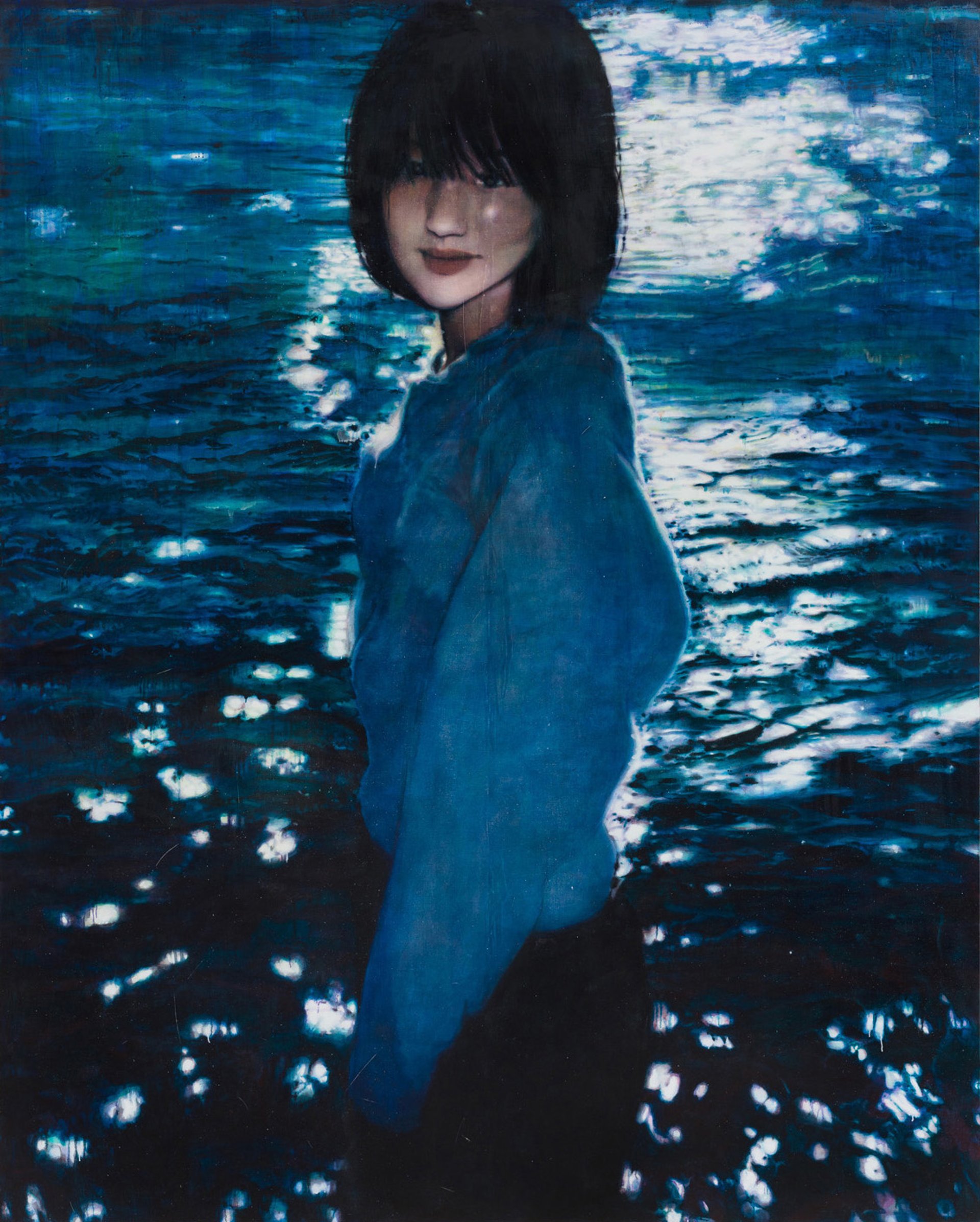

Moka Lee’s Dark Ray 02 (2023) © OnArt studio; courtesy Moka Lee and Jason Haam Gallery

As suggested by her FACE ID show, Lee is particularly drawn to portraits. “I usually have something to say or an emotion I would like to convey with a painting, and then I try to find images that could be effective in delivering this idea. So it is usually very clear when I find the right image,” Lee explains. She always gets people’s permission to use their photos and pays them a small fee. “The finished paintings almost always look very different from the original photograph, so I try to let people know about this in advance,” Lee adds. She distorts the crisp, contemporary, digital image through her painting process, her close cropping and her distinct, muted colour palette that gives her works a far-off, aged feel, like a vintage photograph.

It is not just the ease of sourcing images that makes social media—predominantly Instagram, Lee says—appealing. The artist is fascinated by the semiotics of images posted online. “The message people convey within social media is usually constructed through the various symbolisms within an image, and the written language [in captions] plays a supportive role in creating an impression,” she says. “In other words, people post their pictures with the intention of making others think or feel a certain way, and this phenomenon is seen across borders and generations. I thought this was very interesting because this kind of approach is very similar to the classic discipline of painting, where every little detail within a painting is filled with implications designed to serve the intention of the artist. I wanted to explore this intersection.”

While Lee relies on social media for inspiration, and credits it for helping artists to communicate with global audiences, she also recognises the darker side of the apps. “I think people, because of the algorithms within these platforms, congregate into groups of like-minded individuals. So their thoughts tend to become similar and simpler,” she says. “I find this both intriguing and terrifying.”

• Moka Lee: Face ID, Carlos/Ishikawa, until 15 February

• Jason Haam: Karma II, Frieze No.9 Cork Street, until 15 February

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content