Dubbed the “it” girl of the art world, the highly sought-after Chinese artist Sun Yitian is considered one of the most successful artists of her generation, walking the fine line between art and fashion with ease.

Born in Zhejiang, China, in 1991, Sun graduated from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in China. Her hyperrealist paintings of mass-produced consumer products have charmed collectors. In June of 2024, she achieved a new artist record with the sale of her 2021 painting Prologue, which sold for RMB 2.99 million (around $415,029), including fees, making it the top result for Asian artists born in the 1990s, according to The Asia Pivot analysis.

Last fall, the Beijing-based artist debuted a collaboration with French luxury giant Louis Vuitton. This month, she is the star of “Romantic Room,” a solo show of new work at Esther Schipper in Berlin, her third exhibition with the gallery. “The works on view in this exhibition interweave my personal experiences with the historical changes of Chinese society and culture through the visual vocabulary of China and the translation of Western culture into Chinese daily life,” the artist explained.

Coinciding with the exhibition, we caught up with the artist, who told us about her artistic practice, her approach to fame, and why she decided to pursue a PhD in literature in addition to painting.

Exhibition view: Sun Yitian, “Romantic Room,” Esther Schipper, Berlin (2025). Courtesy the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin/Paris/Seoul. Photo © Andrea Rossetti

You’ve been dubbed the new “it” girl in the art world. How do you feel about fame and success?

I looked up the history of “it girl” online. In 1927, British novelist Elinor Glyn used the term “it” to describe actress Clara Bow in a promotional campaign for a MGM film. Over time, “it girl” became a pop culture term describing young women who are trailblazers in fields such as fashion, society, and the entertainment industry, occupying the center of the media’s and public’s attention. If we go by this definition, it’s nice to be called an “it girl.”

However, I think I may have impostor syndrome. I have discussed this with my good friends, who are also successful women in their respective fields. But we still often feel that we are “impersonating” capable people and attributing everything we have achieved to luck. Such self-doubt might be more prevalent among women. I often find myself in a conflicting situation. On the one hand, fame and success are great, but I sometimes wish I could just hide. It’s like the self-portrait in my new exhibition at Esther Schipper, Berlin, where I put on the so-called “facekini” to shield myself from some of the stares.

Your hyperrealist paintings of toys and mass-produced objects have amassed a major following. Why do you think your work speaks to such a big audience, particularly the young generation and people around your age?

Most artists undoubtedly hope their work will be seen and recognized, and I am no exception. My paintings are visually striking, depicting cute objects that evoke a desire to touch and stroke them. What I aim to express, however, is a surface that is devoid of secrets or depth—it is the “skin” of objects stripped of social and historical context. As a result, people from different cultural backgrounds and with varying levels of aesthetic appreciation will reach different layers of meaning in the images.

A significant reason why my work resonates with many viewers is that I grew up in the same era—an era of rapid globalization—as them, sharing a similar visual language. We all watched Tom and Jerry, played with the same Barbie dolls, and tended to have similar aesthetic preferences. However, I don’t think I can speak for my generation or define what concerns us the most, as everyone is an individual, and it is difficult to distill a universal commonality.

A snapshot of Sun Yitian’s studio in Beijing. Courtesy of Sun Yitian Studio

You are studying your PhD in literature at the School of Humanities at Tsinghua University in Beijing. Why?

Indeed, I am pursuing my PhD in literature. In fact, my focus is more inclined toward philosophy. The theme of my dissertation is “objects” in Western painting history, incorporating theories about “objects” from various thinkers such as Immanuel Kant, Martin Heidegger, György Lukács, and Jean Baudrillard. I have approximately two years left until graduation, and I hope to complete my PhD within a total of five years. I feel that pursuing this degree has allowed me to experience the language and charm of various disciplines. This may leave subtle and gradual impact on my artistic practice. It certainly gives me different points of view on my works.

Last year, you had a collaboration with Louis Vuitton. There was a catwalk show of the clothing line featuring prints of your work, as well as handbags. There was also perfume. How did you find that experience?

I was excited about collaborating with Louis Vuitton, anticipating the transformation of my artworks into consumer products. It was not just a simple appropriation of images, but an extension of their conceptual framework. My practice originates from mass-produced objects labeled “Made in China”, which are manufactured in factories and circulated worldwide at extremely low prices. These “objects” become the protagonists in my canvases, transforming what once seemed ordinary or even cheap into valuable works of art.

Exhibition view: Sun Yitian, “Romantic Room,” Esther Schipper, Berlin (2025)

Courtesy the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin/Paris/Seoul. Photo © Andrea Rossetti

In this collaboration with Louis Vuitton, the images in my work were once again deconstructed, transforming these objects into real luxury goods. According to South Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han, concepts such as “original,” “primordial,” or “identity” from the pre-constructive dimension exist predominantly in Western philosophy, whereas East Asian thought begins with deconstruction—creation stems from deconstruction, and to create is itself to deconstruct.

The interaction between a painting and the viewer is relatively static and silent, a distant observation. However, when my work is reimagined as clothing, bags, or perfume, the distance between it and the viewer becomes closer, and this interaction is alive and uncontrollable. It is an equal, mutual relationship.

Whether or not to try as many different creative methods as possible depends on the individual artist. I don’t know if I will collaborate with a fashion brand again. The collaboration itself is secondary; what is important is whether it is relevant to my creative process.

Tell us about your studio. How does it compare to other studios you’ve owned before? Where is the studio, what kind of space is it, etc.?

I’ve moved several times, and this is my fifth studio. The biggest difference from the previous ones is that it has heating and air conditioning, so I no longer have to stand on an electric heated carpet to paint in the winter, and my hands don’t get numb. It’s located in a village on the outskirts of Beijing, where delivery workers, city cleaners, and many young creatives live. This space was built by a landlord who demolished his old house to create a studio specifically for artists. It’s not very big, but it’s enough for me.

Artist Sun Yitian looks at her dog while taking a short break from working on the fish shoe painting Jingpin (2024) in her studio in Beijing.

Tell us about a recent work of yours that you have put a lot of thought into.

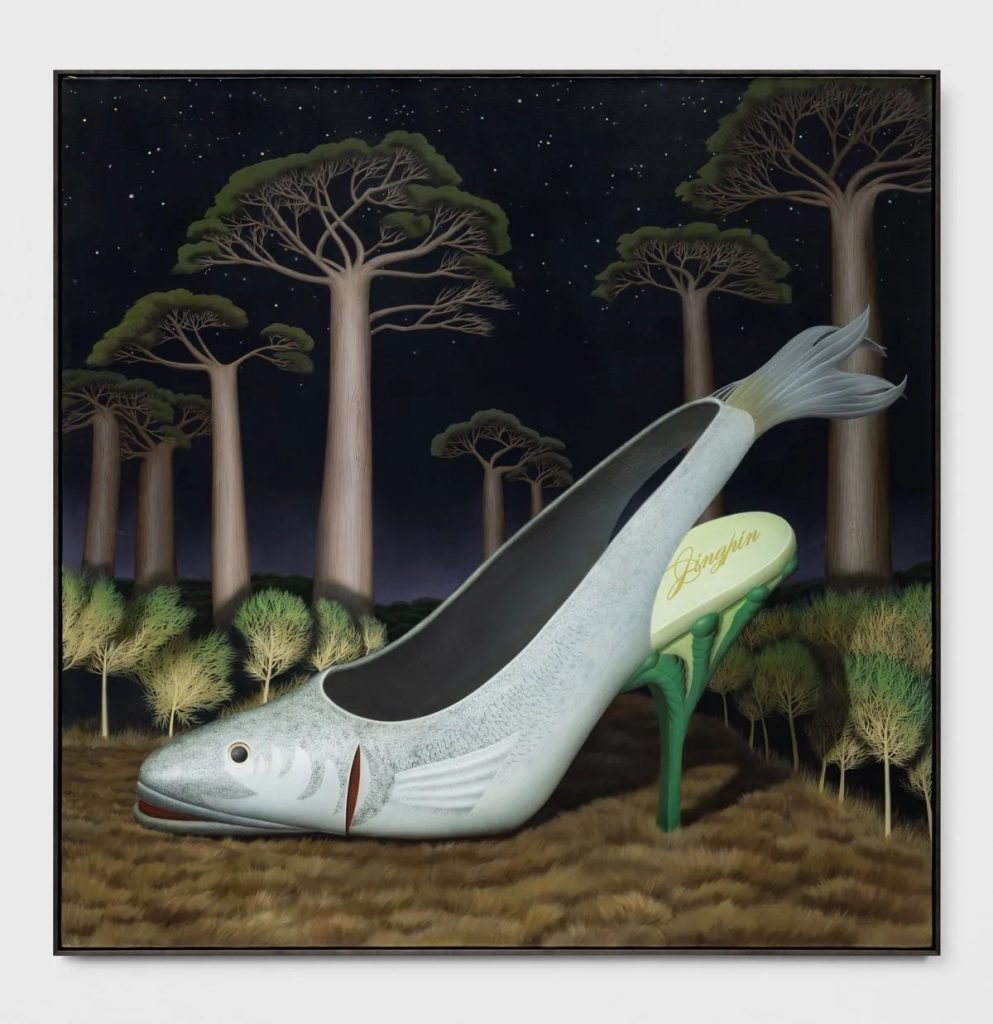

My painting, titled Jingpin, which I created last year and is featured in “Romantic Room” at Esther Schipper, reflects an important reference in my recent practice: the concept of “shanzhai,” which philosopher Han refers to as “Chinese deconstruction.” It is a form of re-creation through appropriation, distinct from the Western tradition of originality.

The image features a “fish shoe,” which features a slingback heel in the shape of a fish. The shoe in the painting was a 1950s design by Andre Perugia, a famous shoe designer born in France in 1893, in the 1950s. He was deeply influenced by the Cubist and Surrealist art movements. His designs caused a huge sensation in the fashion world at the time.

Sun Yitian, Jingpin, 2024. Photo Andrea Rossetti/Courtesy The Artist And Esther Schipper, Berlin/Paris/Seoul

The fish sits beneath an imagined starry sky, against a backdrop of uneven layers of trees, which was painted with the precision of gongbi [meticulous brush technique in Chinese ink painting]. Each stroke demanded courage because mistakes were not an option; a single error meant starting over from scratch. When I finally completed the piece, I let out a deep, heavy sigh of relief.

I was born in Wenzhou, a Chinese city also renowned for shoe manufacturing. But unlike Perugia, Wenzhou was famous in the 1980s for producing counterfeit shoes, or “shanzhai” shoes. I remember that the shoes made in Wenzhou were called “morning-and-evening shoes,” meaning they would break by evening. To cut costs and increase profits, most of these shoes had soles made of paper, resulting in extremely poor quality. However, it was precisely this large-scale industrial production and the development of foreign trade that allowed the southeastern coastal cities to accumulate significant wealth after the implementation of the economic reform and opening-up policies.

A snapshot of Sun Yitian’s studio in Beijing. Courtesy of Sun Yitian Studio.

In the painting, the fish shoe trademark has been replaced with the Chinese pinyin Jingpin, which means “premium quality.” In China, only counterfeit goods or products of poor quality are deliberately labeled with the word “Jingpin,” or are considered counterfeit if they bear this label. The background of this painting is an African breadfruit tree. China’s “Belt and Road Policy” after reform and opening-up also ushered in an era of transformation for Africa.

Over recent years, young Chinese artists have exhibited regularly throughout. Europe and America. How do you compare this attention to that paid to artists from earlier generations?

Compared to the early 2000s, Chinese artists actually receive much less attention internationally now. This is, of course, due to a variety of factors, including economic, political, and broader environmental factors. At that time, they were more often presented as a group, while today’s young artists are more likely to gain exposure as independent individuals. Every era will see the emergence of new young artists, who will continue to grow into mature artists, and then a new generation will follow. Attention will always be there; don’t expect it to stay on anyone for too long. As for myself, I don’t feel burdened by history.

What are your plans for the rest of 2025 and 2026?

I may participate in an Italian residency program in the fall of this year. My most important project right now is my doctoral thesis, which I hope to complete next year. At the same time, I’m looking forward to the school life.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content