In early spring in New York, I sat across from former Sotheby’s rainmaker Brooke Lampley, now a director at Gagosian, as she reflected on one of the most elusive skills in the trade.

“Pricing was one of the greatest educations of my life,” Lampley told me, describing it as a discipline you can only truly master through selling. With skin in the game, you learn fast how to read the room. Valuations based on price data alone lean on a scaffolding of precedent that tells you little about current demand.

A few weeks later, in the auction room Lampley once presided over, an Alberto Giacometti bust with an estimate of $70 million failed to attract a buyer. Experts blamed the flop on sticker shock. Others, noting that Giacomettis have exchanged hands for more than double that figure, saw a deeper signal: A crisis in market confidence.

Ahead of Art Basel 2025, pricing is under scrutiny like never before. Price inflation for living artists has been a bugbear for years and the failures of the spring sales have now rattled assumptions well beyond the primary market.

This isn’t just a matter of price correction, however. It’s a rupture in the logic that once upheld prices as proxies for prestige and demand. Now, $30,000 gets you a resume-light emerging artist, $300,000 a mid-career work no one can flip, and $30 million a lackluster late Picasso. The signals are scrambled. Speculators have vanished. Even seasoned buyers are pausing. The art market has lost its grip on price-setting—and dealers must recalibrate.

The ‘Why’ Behind Price Hikes

In theory, we all know the formula for how pricing is supposed to work—a mix of rational signals and psychological tools. An artist’s career stage, market comps, buzz, institutional recognition, and production costs all factor into the number on the PDF.

Then there are the trade tricks that dealers use to shape perception. “Anchoring” sets a high-price work to make others appear more reasonable by comparison. “Emotional pricing” taps into consumer psychology—round numbers feel transactional, but $3,800 feels thoughtfully calibrated. And a 10 percent discount is practically baked in to the deal, sometimes doubled for institutions.

Artwork by Nora Turato during Art Basel Hong Kong 2025. Photo: Keith Tsuji/Getty Images.

Of course, pricing wasn’t always so codified. Artnet founder Hans Neuendorf recalled that when he first started out as a gallerist, there was no centralized pricing information, everyone had to do their own homework. Dealers would ask around, jot down notes, and compare figures to get a sense of what artworks were actually worth.

“One of the reasons I founded Artnet was the lack of price transparency in the art market. It’s a prerequisite of every functioning market,” Neuendorf said. Artnet’s launch of the Price Database in 1989 changed everything. What was once opaque became measurable—and with that came momentum. Sellers nudged prices upward, buyers met them year after year, and a new normal took hold. “We ended up with a price spiral that went into the millions,” Neuendorf said. “A whole new class of buyers emerged, followed by yet another one: speculators. I didn’t foresee this and certainly didn’t wish for it.”

Total annual sales of fine art at auction increased from a little over $1 billion in the early 90s to more than $10 billion in 2024, according to the Artnet Price Database. While inflation, rising costs, and fair expenses played their role, these factors alone don’t fully account for the exponential price hikes. As the market grew, it got swept up in its own performance. Art became a lifestyle and pricing had to keep pace with the pageantry.

Confusion and Correction

These nosebleed prices, fractured from logic, broke the system for both new and established buyers. Where prices once reflected consensus—all of a sudden, they reflected confusion. In 2025, we are witnessing the consequences through a market correction. Last year, the auction market shrunk 27.3 percent, to $10.2 billion, according to the Artnet Intelligence Report.

Many collectors who bought works at inflated prices with hopes of a future upside are now struggling to make back what they invested. In spring, a painting by the 47-year-old contemporary artist Rashid Johnson sold for $292,100, marking a 72 percent loss for the collector who had paid $816,500 for it in 2022. Meanwhile, significant works by classic American artists like Andy Warhol, Robert Ryman, and even a surrealist titan like Magritte, were withdrawn or bought in.

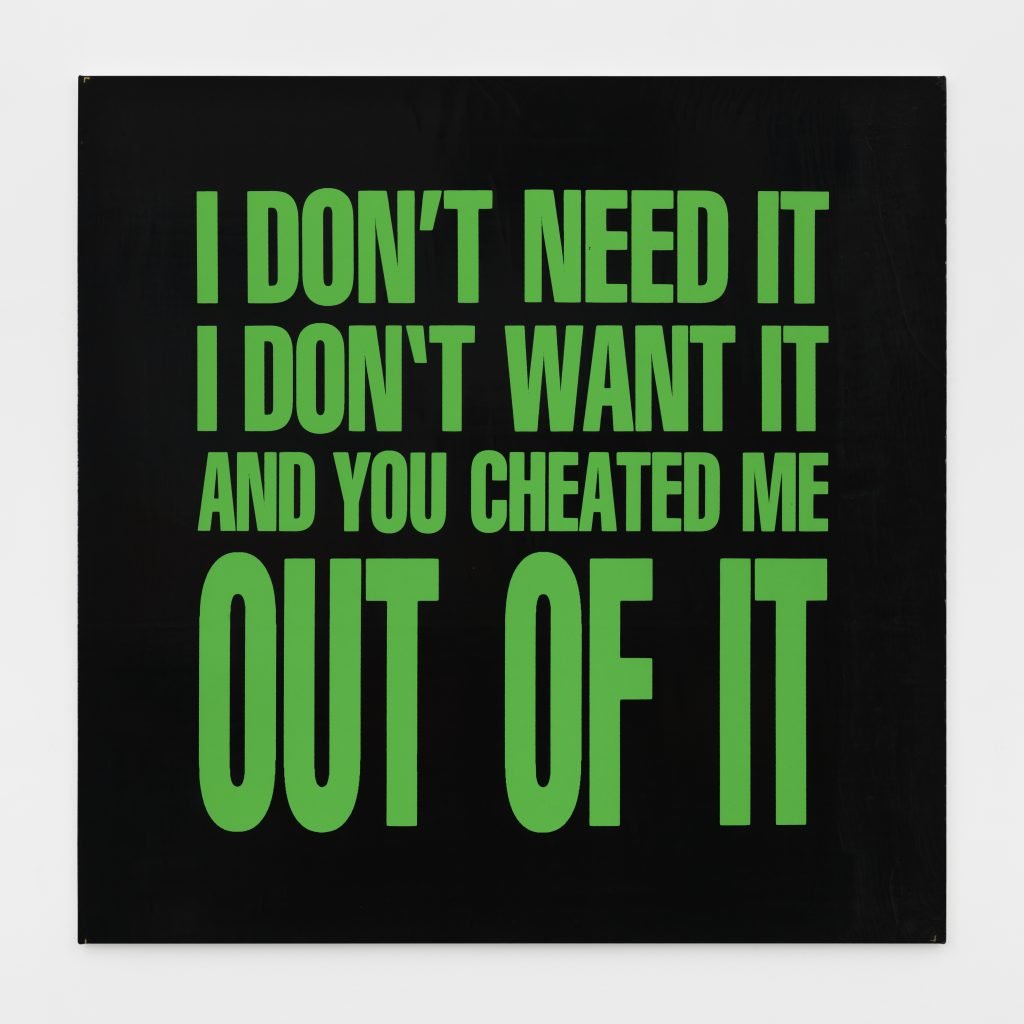

John Giorno, I DON’T NEED IT I DON’T WANT IT AND YOU CHEATED ME OUT OF IT (1989). Courtesy of Thomas Brambilla Gallery (Bergamo) and Giorno Poetry Systems (New York).

Higher prices deterred access for new buyers entering the market, galleries are turning over artists like never before, and all this has left young collectors, who were just getting their eye in, feeling disillusioned. Its borne out in the data: Auction sales saw a 13.8 percent dip in the $10,000 to $100,000 range last year, while sales of works under $10,000 declined 6.3 percent.

Oleg Guerrand, who started his collection in 2016, described to me his personal disenchantment. He said that rational pricing (and whether a gallerist has a reputation for price gouging) impacts his willingness to engage with a gallery’s program. He has scaled back his purchases to two or three works a year, become less impulsive, and has generally retreated from art world gatherings. And he has a strong message for dealers at Art Basel: “Show quality, have a strong, genuine care for the artist, and don’t take buyers for granted,” he said.

Advisor Sibylle Rochat is relieved that buyers are being more careful with their purchases. “A heated market is very hard to work in,” she said. “You don’t do good business and nothing is realistic. If you do good business, it is because you’ve been opportunistic in the market but, as I want a long shelf life in my job, I don’t do good business. How can I advise my client to buy that when I know it’s not worth that price, and will be worth nothing in two years?”

The Danger Zone

The worst offenders? The middle market, or works priced between $80,000 to $800,000. “It became so expensive in galleries for inventory you can find cheaper at auction,” Rochat said.

While this segment appeals to buyers because the artists are more established than emerging talents and the prices are still lower than blue-chip works, “it’s difficult to buy well in the mid-market right now,” she noted. “Anything over $100,000 feels risky.”

While some galleries have lowered prices in the crunch, others are holding the line, usually because they are established galleries, and they have the clientele for it, according to Rochat.

That won’t last forever, though. Laurent Asscher, a seasoned buyer whose collection includes works by Cy Twombly, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Brice Marden, is among those being more cautious with his purchases this year. The Belgian collector, who opened his own foundation in Venice in April, called the inflated middle market for contemporary art “the most dangerous” zone. Asscher warned that galleries (and artists) are alienating their collector base by raising prices too quickly. “At some stage you will need to find new collectors. Or you’ll find yourself in a dead zone with nowhere to go.”

Of course, for many galleries, making adjustments is a point of pride. To lower prices would be to admit that they were ever too high in the first place. But, Rochat said, these dealers may be more open to aggressive offers and hesitate to raise prices further over the next few years.

Some are feeling validated right now. Dealer Marianne Boesky, who is bringing works across her program of emerging to mid-career artists to Art Basel in prices ranging from $40,000 to $2 million, says she has been “very measured” when it comes to pricing her primary market artists.

Martin, ab in die Ecke und schäm dich (Martin, Into the Corner, You Should Be Ashamed of Yourself) by Martin Kippenberger and Untitled by Christopher Wool on display at Christie’s New York in 2021. Photo: Cindy Ord/Getty Images.

“For something as abstract as pricing, we do try to apply a logic to it and try to be sensible,” she said. Prices go up in line with the evolution of an artist’s career, measured by institutional underpinning thorough museum acquisitions, publications, and critical attention. Costs have risen dramatically since covid, but “our conclusion has been we can’t really modify prices based on that,” she said. Nor was she among the gallerists to take advantage of the market bullrun. “It is a long game,” Boesky said. “Some of those careers that get hyped quickly can die just as quickly.” Buzzy gallery artist Danielle McKinney’s paintings have sold for more than $340,000 at auction, but Boesky says her highest priced painting remains a measured $130,000. “We need to manage the pricing for the long term and make sure institutions can continue to afford to acquire the work, and that they go to safe hands so they don’t end up at auction and have a gyrating market.”

Opportunity Awaits

While prices remain inflated in the so-called danger zone, many buyers have simply retreated to galleries working in the lower price points, and as a result that part of the market is broadening. Online-only sales brought in more than $392.8 million last year, according to Artnet, and Art Basel and UBS’s latest report suggests that sales grew 17 percent for galleries with a turnover of less than $250,000.

“People are not willing to take so much risk,” Rochat said, adding: “They want to have fun.”

Asscher said he is always interested in the emerging, priced between $20,000 and $30,000. “At this range, you buy because you like the painting, you want to support the artist.”

Younger dealers who are concerned with longevity are eager not to repeat the mistakes of their antecedents. I spoke to Sonia Jakimczyk, cofounder of emerging gallery IMPORT EXPORT, which has been operating sustainably since 2022. She is showing a video game by Alice Bucknell at Basel Social Club, an unvarnished satellite event to Art Basel, which offers much more accessibly-priced works. “My philosophy is that money now is better than money tomorrow, so I don’t get greedy,” she said, adding that she prefers to take a more honest approach to pricing. “Why price with the intention of coming down by 30 percent? That’s a hustle and I don’t want to be a hustler.”

Still, there is opportunity in this market. “Things start to be safe from $1 million—if you buy well,” Rochat said, adding that she has been more active in the blue-chip range.

If you want a stock of classical pieces, according to the advisor, now is the moment to build it. Look for artists like Kenneth Noland, Robert Ryman, Morris Louis, or even Ed Ruscha; take note of names who didn’t perform well at auction this past season. “If you have deep pockets, make strong offers on these things,” she said, adding an important caveat that there is no guarantee the next generation will have the same taste as the preceding one, so make sure you like it, too.

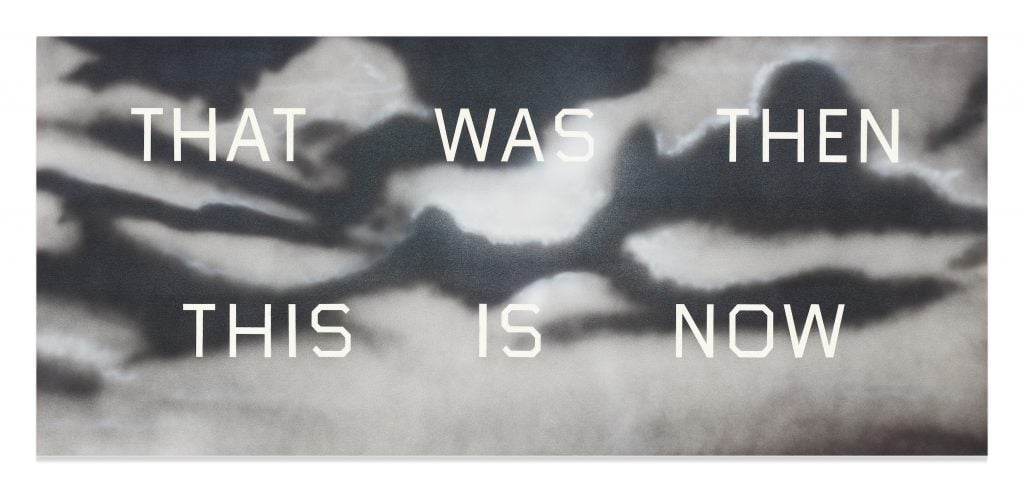

Ed Ruscha’s That Was Then This Is Now (1989). The work hammered at just below its low estimate of $7 million at Sotheby’s contemporary art evening sale on Thursday, selling for $7.8 million with fees.

“For once, I would advise my clients to behave like art dealers. Go to fairs and auctions, and buy only at a hard discount price.”

Asscher will also be on the hunt for the really “first league artists” for whom there is an established market, and will be willing to shell out $10 million or more for the right example. As we spoke, he was fresh from buying a painting by Christopher Wool. “It’s a very good time to buy Christopher Wool,” he affirmed. (Artnet’s Art Detective Katya Kazakina recently explored why Wool’s prices have dropped.)

Reading the Room

Market opportunity notwithstanding, there remains a key question underpinning Art Basel: Mood.

“Things have slowed down but I don’t think they’ve slowed down for us because of price points, it’s more about psychology,” gallerist Boesky said. “There’s a lot of anxiety in the world.”

Robert Landau, of Landau Fine Art, a renowned dealer of Impressionist and Modern art who has been in the business for 37 years, echoed this sentiment. He pointed to the chaos Donald Trump has sowed in the market and elsewhere, wars in Ukraine, Israel and Gaza, Sudan, and more. “It’s not the art market that’s the question mark today. It’s the world. The world is on edge,” Landau said.

“You cannot be satisfied that the art market is detached from all of what’s going on around us. It’s everywhere, it’s very disturbing, very upsetting. Then you want to turn around and figure out how much is a Rembrandt worth? Or how much is anything worth in today’s world—a condo in London or a shack in the Bahamas?”

The dealer uses the example of a masterpiece in his stock right now, which he says could be worth anywhere between $25 million and $100 million “depending on the mood of the buyer.”

At the very top end, price isn’t about data. “It’s the subject of what somebody is willing to pay, and what somebody is willing to accept for it,” Landau said, adding that the secret to longevity in the market, “is about knowing what to buy. Not at what price.”

The veteran dealer remarked on the dramatic changes to Art Basel during his tenure, including the explosion of “so-called art advisors,” doling out bad counsel. “When I first went there, it was about art. Today it’s about money,” he said. “People are greedy, and they don’t care about morals. At auction houses it’s worse; all these people who don’t tell you the truth.”

After modest results at TEFAF in New York, Landau is not expecting to do good business in Basel. Still, this has not deterred him from bringing “the best” he’s ever brought to the fair. The collection of 76 items includes what he described as one of Henry Moore’s most important lifetime carvings.

Restoring confidence in the market will take more than price adjustments, according to Landau. “If you could take those big issues—Trump, Palestine, Ukraine—and solve them, the world would heave a sigh of relief, including me,” he said. “And people would feel better about buying a painting. Whether that’s for $100 or for $100 million dollars.”

So What Happens Next?

What the market has lost isn’t just money—it’s meaning. Galleries have long pitched art as an investment. That narrative is fraying. Perhaps now is the moment to tell a different story: That art pays other kinds of dividends. Maybe value isn’t just what the next buyer will pay. Maybe it’s what the work gives you while you live with it.

That’s how seasoned collectors like Asscher have always seen it. “I am creating a collection, I’m not a dealer,” he said. He’s sanguine about the fact that some of the artists he has bought over the past few years have depreciated in value. Is he still buying from those dealers? “Yes,” he said. “They never forced me to buy.”

Even advisor Rochat, for all her cool-headed caution, admits: “Basel is the only fair where I fall in love at first sight.”

Landau also breaks from his curmudgeonly musings to give some good advice: never stop looking. “There’s still a new Lucien Freud out there somewhere who’s going to be the star of tomorrow.”

As we head into one of the biggest weeks in the trade, it’s true to say that business is tougher. But the art still moves—on feeling, not just figures.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content