AFTER HER FIRST son was born in 2018, the painter, sculptor and conceptual artist Camille Henrot returned to the studio, eager to make work about anything other than birth. But to her surprise, sheets of blank white paper had become unbearable, and she soon found herself painting them a deep red, a color she’d never been drawn to before. “The whole studio looked like a blood factory,” she said, laughing. One day she went out to walk her dog, and a stranger asked if she was OK. She realized that her clothing was smeared with red paint — she looked as if she had just been through some violent event. “Am I OK?” she wondered. Maybe the aversion to white came from memories of being in the hospital, she thought. Or maybe it was about understanding “the dark side of the worship of purity and minimalism.” Whatever the reason, she started making many red paintings, some of which depicted women pumping milk.

She had stumbled into a gap in art history. While there’s no shortage of representations of mothers with their children, Henrot could find few of mothers on their own. The mother is “never dissociated from the gaze that turns her into an object or attribute of the child,” she writes in a 2023 essay called “Pump and Dump.” She thought of the pervasive image of the Pietà, but “that is a very disagreeable archetype because it’s an archetype of extreme suffering,” she told me recently. How, she’d wondered, could she portray a mother in a more neutral situation, as a subject in her own right?

Henrot scoured books and the internet for images of breast pumping — a technology that had been in use for millenniums but had almost never been depicted in painting. It’s a task that represents so many of the contradictory demands of motherhood — sitting still amid what can feel like nonstop motion, performing labor that isn’t compensated or particularly valued yet can also be a source of pleasure and pride. For Henrot, the hours she spent pumping were a nice break. The swooshing of the breast pump was soothing. It reminded her of summers in her youth when she milked goats at a farmhouse that her family rented in Chamonix, France.

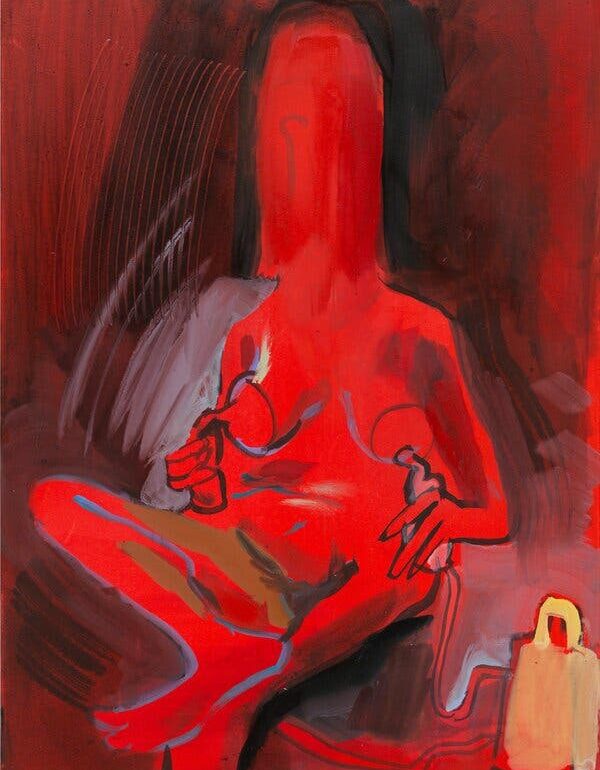

The drawings and paintings that emerged from her pumping research became part of a series she titled “Wet Job” (2018-20). Like many of Henrot’s works, they are elegant yet childlike, with a tint of menace. In one, a brilliant red figure sits naked, with one leg folded across her knee, a pump attached to each breast, their cords snaking back to a compact yellow case. Her posture is relaxed, her big toe flicked upward, perhaps keeping time to the pump’s rhythmic underwater sounds. Her head is elongated, as if in a medieval helmet or a shroud. Milk seems to leak out of the pump onto her right breast and pool on her stomach. The image is ambiguous: inviting and sensuous and also a little gross, which is exactly what pumping is like, and the intersection where Henrot likes to place her work.

MOTHERHOOD HAS LONG been put in tension with serious art making. The feminist pioneer Judy Chicago, 85, lamented in 1985 that “as soon as one gives birth to a child, one is no longer free,” writing sympathetically of “a highly gifted artist whose conflicts between self-fulfillment and her child’s needs tear her apart with guilt.” Two decades later, Tracey Emin, now 61, whose most famous artworks include a catalog of the people she’s slept with and an installation of her own disheveled bed, said, “There are good artists who have children. … They are called men.” (Chicago and Emin never had children.) The conceptual artist Mary Kelly, 83, described being a woman artist as a “double negative.” Her own piece “Post Partum Document” (1973-79) is a rare example in contemporary art of a mother making serious work from her experience. In “Document,” Kelly investigated her son’s development — printing diagrams drawn from Lacanian psychoanalysis alongside her son’s stained diaper liners, making casts of his tiny hands and indexing minute shifts in his behavior.