I am suspicious of people who do not like art fairs. If you love art, how can you not get at least a little pleasure from seeing hundreds of artworks—and probably thousands of artworks—in one convenient location? It’s a miracle! Of course, I get it. Fairs are often overcrowded, with both humans and art, and the quality of that art varies wildly. Only particular kinds of work tend to be on view at them. Fairs “are about what money likes,” as the critic Peter Schjeldahl once put it. As for fair venues, they range from inoffensive to unpleasant.

At their best, though, fairs are atlases to the state of play in art, tools for learning about far-flung galleries, wormholes into other universes. When one offers a fresh approach, we should cheer, and as I look back on my art highlights of the past year, I keep returning to Art Collaboration Kyoto, which I attended last month to take part in its public programming. ACK is a young endeavor—this was its fourth edition (my colleague Vivienne Chow has a full report from the ground)—and it is glorious, a model that should inspire other fairs, big and small, to up their games, to take some chances. Let’s run down its pleasures.

Drawings by Kazimir Malevich and ceramics by Raku Jikinyū XV in a booth shared by the galleries Annely Juda Fine Art and Mitochu Koeki. Courtesy of ACK, photo by Moriya Yuki

1. Size. ACK had 69 exhibitors, a very manageable number. Earlier this month, Art Basel Miami Beach had about four times as many, 283, which means that if you spent one minute in each booth, you would need more than 4 hours to see it all. (No one sees it all.) There were only about 40 booths at ACK, due to its sui generis conceit: The majority paired a Japanese gallery and a gallery from abroad. Another 13 stands had solo displays “with distinct connections to Kyoto,” as the fair put it.

An aside: As a general rule, bigger is typically better when it comes to art fairs, I think. The critic Dave Hickey said that “98 percent of what we see is bad art,” but that “when it really comes down to it, a lot of what we learn about art, we learn from bad art.” At fairs, it’s probably more like 99 percent bad art, but since it’s going to be rough going anyway, we may as well have more of it. Strolling the aisles becomes a kind of treasure hunt.

But ACK’s succinct approach was refreshing. It made it possible to see the whole fair at a leisurely pace, and dealers were in fine form, uniting unusual, intriguing artworks. Since about half of them hailed from Japan, a foreigner got to see a bounty of less-familiar material (instead of a bunch more Ugo Rondinone paintings).

Annely Juda Fine Art, of London, brought small, precise, but almost casual pencil drawings from the 1910s by Kazimir Malevich to present alongside rugged and elegant new ceramic tea bowls by Raku Jikinyū XV (the 15th head of the ceramics-making Raku family), from Mitochu Koeki, of Tokyo. (The intimate Raku Museum in Kyoto is filled with the family’s creations; no photos are permitted, otherwise I’d plaster them here.)

A solo display of paintings by Andreas Eriksson at ACK, presented by Neugerriemschneider. Photo: Moriya Yuki, courtesy of ACK.

Los Angeles’s Chris Sharp Gallery had bewitching Glenn Goldberg paintings of birds and flowers in a pointillist, faux-textile style that paired fruitfully with photographs of flowing water by Shibata Toshio, brought by Osaka’s Yoshiaki Inoue Gallery. There was also a virtuoso effort by Taro Nasu (Tokyo) and Matthew Marks Gallery (New York and Los Angeles), with radiant spools of lightbulbs by Sturtevant (doing Félix González-Torres) spilling down to the ground and forming a ring, near a classic plastic wall piece by Marcel Broodthaers. And in the solo section (“Kyoto Meetings,” it’s called), Berlin’s Neugerriemschneider had an array of lucid abstract paintings that the Swedish artist Andreas Eriksson painted in Japan.

Sizes and prices of artworks tended toward the modest—no one was getting rich at ACK, but they also were not spending much. A certain ebullience filled the air. “I feel like I’m on a side quest,” one dealer told me, referring to a video game plot that breaks off from the main narrative, involving tasks that are wholly optional and that carry their own rewards. We could use more side quests.

2. Price. Adult tickets to the fair went for ¥3,000, which is about $19.50, a fairly humane price, and high school and university students had to pay half that. In contrast, Frieze New York charges a whopping $76 for a general-admission ticket, and Miami Basel an astonishing $85. Sure, you get to see a lot more art at those fairs, but those are still tough numbers for most to swallow. I know, I know, these are trade fairs charging what the market will bear, and they have no real obligation to the general public, but I feel some sadness for anyone shelling out that kind of cash. (As a member of the press, I never pay to visit an art fair, and the idea of doing so frankly disturbs me.)

Lee Kit, Laundry (2024), part of an exhibition accompanying Art Collaboration Kyoto at the Kyoto International Conference Center. Photo: Andrew Russeth.

3. Venue. ACK takes place at the Kyoto International Conference Center, a grand, intricate, and angular venue designed by the Metabolist architect Sachio Otani, filled with all sorts of surprising details—a tranquil sea of stones here, some geometric wall paintings there. It opened in 1966, has been renovated a few times, and is in immaculate condition. (This is Japan.) You could imagine the good guys in a sci-fi epic using it as their command center for a vast intergalactic war.

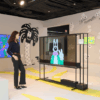

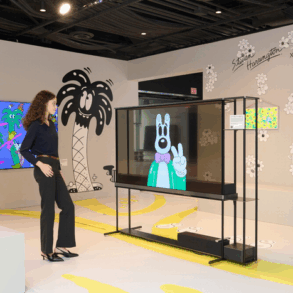

The fair design was handled by the local architect Takashi Suo (whose projects have included a house for the artist Danh Vo, a discerning figure). Suo conceived of a kind of dispersed or deconstructed marketplace, banishing a gridded layout (in most areas) so that you wandered as if moving through the alleys of historical Kyoto. Suo also left the exterior walls and beams of booths unpainted and exposed, and some exhibitors hung paintings on them. Marks tucked a hairy cheese sculpture by Robert Gober on a humble shelf in one of these areas: nice.

Installation view of Lucas Arruda’s solo show at the Daitoku-ji Ohbai-in temple in Kyoto. Courtesy of the artist and Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo, Brussels, Paris, New York. Photo: Nobutada Omote.

4. Extracurricular Activities. When you’re visiting a 1,300-year-old city with more aesthetic and spiritual delights than one could experience in a lifetime, you don’t want to spend too much time in a convention center (even a nice one). ACK facilitated sterling off-site projects in historical venues, and dealers organized still more.

The Chinese artist He Xiangyu arrayed a variety of sculptures around the Manshu-in temple, which has been in its present location since the 1650s, and stood a metal sculpture of a boy in its rock garden (a sort of alarming sight).

A few of Lucas Arruda’s hazy, almost-ghostly paintings hung in rooms at the Daitoku-ji Ohbai-in temple, a project organized by Mendes Wood DM, which participated in the fair. Arruda’s paintings have always felt a little too precious for me, but here, they had a quiet dignity. They made sense.

A painting by Eriksson at the Murin-an garden in Kyoto. Photo: Andrew Russeth.

But the aforementioned Eriksson won the week, staging an exhibition in a building at Murin-an, a traditional garden at a 19th-century villa. One of his large paintings—a field of craggy slices of color—filled a room with tatami mats, its door open to the elements. It was drizzling outside, and his picture felt alive, as organic and ever-changing as the surrounding plants. “I can’t believe I’m here,” another dealer marveled to me on the street later in the day. I understood what he was saying.

5. Childcare. ACK offered on-site childcare for kids up to age 7 “in order to make it possible for all people with small children to be involved in the arts,” as it says on its website. As a parent of a small child, I was moved. The daycare was staffed by Rakuwakai Otowa Hospital employees, and parents had to sign up in advance, answering questions about their child’s favorite toys, sleeping habits, and so forth.

An egg sandwich at Sonoba’s stand at ACK. Photo: Andrew Russeth.

6. Food. We do not need to rehearse the culinary horrors of so many art fairs here. ACK kept it simple, inviting a handful of esteemed local proprietors to offer one or two coveted items apiece. Loose Kyoto sold hearty but not-too-sweet donuts, while the esteemed soba maker Sonoba hawked transcendent, melt-in-your mouth egg sandwiches on white bread. I would like one of them as part of my last meal.

Can Art Collaboration Kyoto keep its magic alive? The dealers on hand in November, an eclectic and smart bunch, certainly seemed happy. The fair’s leaders will probably be able to attract more of them. The modest scale of the event, and the fact that galleries must be invited to apply, means they can control for quality.

Many powerful interests are betting on ACK. The fair’s organizers included Kyoto Prefecture, the Kyoto Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and the Contemporary Art Dealers Association Nippon (sort of the Japanese equivalent of the Art Dealers Association of America), and among its supporters were the Japanese government and the Japan Tourism Agency.

On ACK’s opening day, I met up with Hayashi Yasuta, the indefatigable director of Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs. He’s been working to build his country’s art industry by trying to ease burdensome tax regulations and encouraging investment. Art sales in Japan account for just 1 percent of the global market right now, according to one recent study. The country does rank second in Asia, but with only 5 percent of the total market to China’s 80 percent.

Last year, Hayashi helped launch a National Center for Art Research, which “will support museums, act as a connector between Japanese museums, and also as a window to the international art world,” he said through an interpreter. In Japan, “the museums themselves are a little bit still stuck in the past,” he said. He is not wrong. Most do not have global reputations equal to the quality of their collections and their programming. There are too few partnerships with peers abroad. Websites are often charmingly outdated.

Museum directors and curators from elsewhere in the world should stop by ACK next year, take some meetings, and perhaps buy some art. High pleasures await them, at the fair and beyond it. Hop in a car from the Kyoto International Conference Center, and in 10 minutes you can be at the Shugakuin Imperial Villa, which the retired Emperor Go-Mizunoo built in the mid-1600s. Climbing its sylvan paths, you ascend from one perfect, rustic retreat to another. The wind is blowing, and the air is fresh. Birds are singing.

The Shugakuin Imperial Villa in the eastern hills of Kyoto, a car ride from Art Collaboration Kyoto. Photo: Andrew Russeth.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content