Abstract

Surging numbers of older parents have migrated with adult children to developed urban areas under China’s internal family migration, experiencing several difficulties in social integration in local society. Social media has become an essential tool for older adults to gather information, socialize, and entertain. However, few studies have focused on the relationship between social media use and social integration among older migrants and the underlying psychological mechanisms. Drawing on the Media system dependency (MSD) theory and the Stress-buffering hypothesis, this study developed and tested a conceptual research model by conducting a cross-sectional online survey study (N = 1001). The results indicate that understanding and orientation, rather than entertainment, are two primary motivations for trailing parents to use social media. The activeness of social media engagement (exposure condition), rather than the intensity of social media use (selective exposure), can positively influence the social integration of older migrants. Psychological resilience cannot mediate the relationship between social media engagement and social integration, which is proved to be mainly achieved through perceived social support and the partial chain mediation of perceived social support and psychological resilience. These findings shed theoretical and practical light on the design of older migrant-friendly social media apps and the efforts of adult children and communities to enhance the social integration of older internal migrants through social media engagement.

Introduction

China’s four decades of economic boom since the 1980s have engendered an unparalleled phenomenon of extensive internal labor mobility from remote rural areas to densely populated urban areas, from impoverished inland regions to the eastern coastal cities. Until then, more than 900 million Chinese inhabited urban areas, accounting for 63.89% of the total population (China National Bureau of Statistics (CNBS), 2023), which is 14% higher than in 2010 (49.68%) (CNBS, 2011). Massive labor migration of the younger generation has weakened traditional family support systems. To bolster intergenerational mutual support within the framework of traditional filial piety, a growing cohort of parents, aged over 50 and hailing from rural areas, are relocating to urban centers to either care for their grandchildren or reunite with their adult children in retirement, all while retaining their Hukou in hometowns. China’s Hukou, or household registration system, is an institutional tool for controlling population mobility and preventing unplanned migration by mandating an individual to reside and work in only one location that is officially registered and permitted (Liu, 2005). These older parents are, in this sense, temporary migrants, officially known as the floating population. This phenomenon gives rise to a distinct group of internal migrants known as “older migrants following children” or “trailing parents” (Dou and Liu, 2017). The number of older floating populations in China consistently climbed from 2.766 million in 2005 to 17.784 million in 2018 and 20 million in 2022 (CNBS, 2023).

For trailing parents, many barriers exist to successful integration into the local society. The Hukou system differentiates the opportunities and entitlement structures between temporary migrants and local residents (Liu, 2005). The absence of local hukou restricts older migrants’ access to public social benefits comparable to those of local residents, such as equitable medical reimbursements, a primary obstacle to their integration into the host society (Jia et al., 2022). In addition, older adults’ capacity to effectively learn and utilize information technology, understand social environments and maintain physical functioning and mobility gradually diminishes as they age (Macedo, 2017), exacerbating the relocation process’s complexity and arduousness. Besides, shifting lifestyles and barriers of dialects and customs make it harder for them to adapt to new living environments (Dou and Liu, 2017). Furthermore, the break with original social support networks has immersed them in deep nostalgia, leading to their reluctance to establish new identities. Marginalized in power in their children’s homes but with demanding intergenerational care responsibilities, they usually feel alienated from the new surroundings due to minor conflicts with their children over educational beliefs (Lyu et al., 2023).

In such a predicament, information and communication technologies (ICT), particularly social media platforms, have been confirmed to be a crucial tool for enhancing the quality of life among older adults (Ihm and Hsieh, 2015) and the social integration of migrants (Brandhorst, 2023; Wei and Gao, 2017). Social media is defined as “the internet-based applications for human interactions and connectivity, as well as information aggregation by users” (Aichner et al., 2021, p. 220). In China, the ratio of older Internet users aged 50 and over has increased from 7.3% in 2014 (China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), 2014) to 30.8% in 2022 (CNNIC, 2023). Instant messaging and online short videos have emerged as the application categories with the highest penetration rates among China’s elderly Internet users. In specific, WeChat and Douyin (Chinese version of TikTok) have emerged as the two most popular social media apps among China’s “silver-haired” users, with penetration rates of 90.6% and 84.8%, respectively (CNNIC, 2023).

With social media effectively increasing older adults’ sense of social connectedness, a growing body of research has demonstrated that social media engagement provides a critical precursor to older immigrants’ social integration (Millard et al., 2018; Näre et al., 2017). Nevertheless, this well-established relationship between social media usage and social integration has rarely been validated among trailing parents under the prevailing urban migration trend. Influenced by traditional Confucianism, they are burdened with demanding household and grandchildren caregiving obligations. The moral imperative of intergenerational support makes it impractical for them to participate freely in local communities (Jia et al., 2022). Thus, focusing on this group is valuable due to the distinct socio-cultural background and relocation purposes. Furthermore, although prior literature has identified technological (Vaziri et al., 2020), psycho-social (Zhao, 2023), socio-demographic (Berner, 2014), and physical factors (Wilson et al., 2023) as determinants of social media use among older adults, there is a paucity of academic research to examine the predictors from an individual-media relationship perspective, especially in milieu of migration.

Additionally, while existing studies have explained the role of migrants’ social media use on their social integration through promoting social capital (Zhao et al., 2021a; Bucholtz, 2019), maintaining and expanding social connections (Forbush and Foucault-Welles, 2016; Lim and Pham, 2016), and media content consuming (Wilding et al., 2022; Wilding et al., 2020), the underlying psychological mechanism has rarely been explored. In particular, the importance of the internal protective force, attributed to individuals’ inherent personal traits/qualities that enable them to endure and even thrive in the face of adversity, has been neglected. Psychological resilience has proven to be a vital endogenous resource for immigrants to buffer against negative emotions for better psychological well-being (Jordan and Graham, 2012) and social integration (Huang et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2019). As such, it is reasonable to include the protective effect of the inner strength in the mechanism of the current study.

To fill the gaps mentioned above, this study aims to determine what types of utilitarian goals can motivate trailing parents to use social media platforms and explain how social media engagement promotes their social integration in host communities from a psychological perspective. Thus, this study examines the cross-sectional data by applying partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to unveil the relationships among the theoretically connected variables in the path model. We draw on the Media system dependency theory and Stress-buffering hypothesis, embarking on an in-depth analysis of the three media dependency relations determining social media engagement and the underlying psychological process encompassing internal (psychological resilience) and external protective (perceived social support) factors. The present study also seeks to examine the association between external and internal protective factors inside this mechanism.

Theoretical background

Media system dependency (MSD) theory

This study introduced the Media system dependency (MSD) theory to investigate the factors influencing older migrants’ social media use from the perspective of individual-media relationship. The notion of “dependency” represents the interdependent relationships among media, societal structures, and individuals. In a post-industrial era, when interpersonal networks no longer provide sufficient information for daily life, the mass media system has become a crucial information system as it controls society’s information resources. As such, MSD is originally proposed as “the relationship in which the capacity of individuals to attain their goals is contingent upon the information resources of the media system” (Ball-Rokeach, 1985, p. 493). One stream of prior scholarship has applied MSD relations to the analysis of offline mass media, such as newspapers (Loges and Ball-Rokeach, 1993), television (Grant et al., 1991), and radio (Loges, 1994). With the proliferation of digital information technologies, the power of mass media is waning. Instead, there is a striking shift toward a growing dependency on emerging digital media. A growing body of research has applied MSD theory to social media applications (Kim and Jung, 2017; Chiu et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2021), e-commerce (Patwardhan and Yang, 2003), mobile technology (Jiang and Li, 2018), and ubiquitous media system (Carillo et al., 2017; Gong et al., 2022).

However, thus far, the academic application of MSD on social media adoption has not adequately addressed the older population, let alone in the context of migration, a gap that this study will fill. According to Loges (1994), dramatic life changes can cause a sense of ambiguity and threat to the environment, which can motivate individuals to seek information through the mass media. Despite diminishing physical mobility and social cognitive ability, trailing parents separate from their original social networks and relocate to a new city in old age. Consequently, they face significant ambiguity regarding their relationship with their adult children and their adaptation to the local way of life (Dou and Liu, 2017). With the increasing penetration of the Internet among older groups, it has been confirmed that social media platforms offer older migrants a valuable and easy means of maintaining and cultivating social connections, accessing information and services, and relaxing (Kouvonen et al., 2021). As such, it is reasonable to suppose that the MSD model is applicable to the context of this study.

Kim and Jung (2017) proposed the concept of SNS (Social Networking Sites) dependency, defining it as “the degree of perceived helpfulness of an SNS for fulfilling a range of critical goals in everyday life” (p. 2). Delighted by Kim and Jung (2017), this research conceptualizes the term “social media dependency” as an individual’s perceived usefulness of social media usage in achieving a set of critical problem-solving goals. In addition, the original MSD model categorized media-dependent effects into three levels: selective exposure, exposure condition, and post-exposure communication (Ball-Rokeach, 1985). The first two effects pertain to behaviors related to media usage. Selective exposure refers to the selection of media forms or content, manifested in the time length or frequency of use. Exposure condition, on the other hand, relates to the degree of activeness of users in engaging in various types of media content or activities. As such, apart from investigating the intensity of social media use, the current study proposes the term “social media engagement” to examine the exposure condition of older migrants using social media.

Stress-buffering hypothesis

Perceived social support, a concept derived from the Stress-buffering hypothesis, was brought in to investigate the psychological factor associated with the external social environment. The Stress-buffering hypothesis posits that social support acts as a crucial buffer (moderator or mediator variable) to protect individuals’ physical and psychological health in stressful conditions (Wilcox, 1981). This support encompasses various forms of aid from social networks, such as emotional support, informational guidance, companionship, and material support (Cohen and Wills, 1985). In contrast to received social support, perceived social support has been widely proven to be a significantly more effective predictor of well-being (Eagle et al., 2019; Kaniasty and Norris, 2009), which is selected by this study.

Prior research has substantiated the notable impact of perceived social support in alleviating acculturative stress (Lim and Pham, 2016) and improving perceived integration (Ho et al., 2014) among migrants. In addition, the role of social media usage in improving perceived social support has been confirmed (Yue et al., 2023; Sitar-Taut et al., 2023). Older urban migrants are under multiple stressors, such as struggles in adjusting to new social environments and lifestyles, the burden of caring for grandchildren, and the shifting roles from family authority to redundant members (Lyu et al., 2023). Therefore, it is plausible to apply the concept of perceived social support to elucidate the psychological process of this group who engage in diverse social media activities as they progressively integrate into the local society.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Social media dependency and social media usage

Individual-media dependency relations can be categorized into three types: understanding, orientation, and play (Loges, 1994). Understanding refers to individuals’ purpose for understanding the world and living in it. Orientation represents effectively and appropriately engaging in personal behavioral decisions and interpersonal interactions. Play is attributed to the demand to relieve stress in life through entertainment activities or interaction with others (Loges, 1994). Each MSD relation can be subdivided into individual and interpersonal (social) dimensions. It has been well documented that three media dependency relations are likely to induce distinct effects on the exposure condition of social networking sites (Chiu and Huang, 2015; Jiang and Li, 2018; Zheng et al., 2021).

Social media platforms have evolved into a collection of diverse sources of information, encompassing traditional news media, online or social news sites, celebrities, families, and friends. They can provide a wealth of messages and discussion forums about current events and news (Kim et al., 2019). In addition, social media users can form and reinforce self-understanding and identity through interpersonal exchanges and acquiring information from mass media (Kim et al., 2019). In the context of our study, Millard et al. (2018) posits that a primary incentive for older migrants to use social media is to access information, such as healthcare information, online news, and discussion forums. Therefore, social media facilitates the process of clarifying uncertainty regarding their external surroundings and maintains their engagement with matters of interest.

In addition, social media can consolidate multiple information sources into a single platform, offering users valuable insights, firsthand experiences, and recommendations to aid in decision-making processes, such as online shopping (Yang et al., 2015), political engagement (Jun, 2020), and healthcare (Fu and Xie, 2021). Regarding interaction orientation, users can acquire social skills by passively browsing various content, such as observing or reading about others’ stories or experiences (Zheng et al., 2021). They can also gain experiences by actively engaging in online interpersonal interactions (Kim and Jung, 2017). In specific, social media has become indispensable for older migrants to avail themselves of services, such as online banking and shopping. As they experience a steady decline in physical mobility, these online services decrease their dependence on families and local friends for direction on behavior (Millard et al., 2018).

Moreover, the ubiquitous accessibility of social media allows users to easily escape from reality during their leisure time. They can peruse the status updates of others to indulge in captivating narratives, pictures, and videos (Kim and Jung, 2017). Moreover, individuals can watch interesting content on social media with others face-to-face, chat with others online, and share enjoyable content with online friends (Kim et al., 2019). Older migrants who are prone to feelings of loneliness and grief find solace and enjoyment in the engaging information on social media, which momentarily distracts them from the real world (Baldassar and Wilding, 2020).

Consequently, these needs-gratifying experiences create a feeling of intimacy with content providers (Chiu and Huang, 2015), leading to increased loyalty towards the creators and emotional attachment to the online platforms (Zheng et al., 2021). Based on this, the intention to continually use social media will increase (Chiu and Huang, 2015). Thus,

H1: Understanding dependency relation positively affects the social media engagement of trailing parents.

H2: Orientation dependency relation positively affects the social media engagement of trailing parents.

H3: Play dependency relation positively affects the social media engagement of trailing parents.

Intensity of social media use, social media engagement, and social integration

Social integration, within the context of migration, refers to the process of achieving social cohesion by incorporating individuals from diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds into the mainstream social structure. This process involves active participation in meaningful social and occupational activities, ultimately leading to the acquisition of citizenship and a new identity (Adachi, 2011). The study focuses on the subjective sense of belonging and emotional attachment to the host communities, which represents the final stage of social integration (Glasgow and Brown, 2006). Numerous studies have empirically confirmed the positive effects of social media adoption on the social integration of migrants (Croucher and Rahmani, 2015; Forbush and Foucault-Welles, 2016; Wei and Gao, 2017; Zhao, 2023; Zhao et al., 2021a; Zou and Deng, 2022). Information exchange and digital imagery on social media can create digital togetherness to maintain bonding social capital from distant family and friends. These engagements help migrants retain emotional stability and find solutions to everyday stressors (Brandhorst, 2023; Baldassar and Wilding, 2020). Migrants of the same origin can form an empowering online space through social media, where they can offer support to each other and cultivate online and offline friendships with similar others or locals. These new connections can promote more active engagement in local communities (Lim and Pham, 2016). Furthermore, migrants can use social media to cement functional relationships with locals already established offline, enhancing their adaptability and a sense of belonging (Bucholtz, 2019; Forbush and Foucault-Welles, 2016).

Even so, the general intensity of social media use (frequency or time spent) has been found to fail to enhance social integration (Wei and Gao, 2017; Zhao et al., 2021a; Zhao, 2023). The actual time or frequency of use provides unclear indications of different engagements (Phu and Gow, 2019). Besides, spending too much time playing games or passively scrolling through other’s latest updates negatively correlates with social integration (Zhao, 2023). In contrast, actual engagement in social media activities, especially positive and interactive ones, can improve social integration (Wei and Gao, 2017) and life satisfaction (Yoo and Jeong, 2017). Therefore,

H4: Older migrants’ intensity of social media use has a negative effect on their social integration.

H5: Older migrants’ social media engagement has a positive effect on their social integration.

Social media usage, perceived social support, and social integration

Within a semi-bounded system, individuals on social media can construct a public or semi-public profile. This feature allows them to preserve their existing social connections in the real world while expanding their supportive networks through the acquaintances they make on the platform. The heightened pervasive awareness of online networks leads to an improved perception of social support (Li and Peng, 2019). Older adults rely more on social media to maintain supportive connections with strong ties (families and friends), which serves as an essential emotional resource in isolated situations (Rosen et al., 2022). Thus, the relevance of social media engagement to immigrants’ perceived social support is subsequently validated by several empirical investigations (Lu and Hampton, 2017; Shensa et al., 2016; Taiminen and Taiminen, 2016; Sitar-Taut et al., 2023).

On the other hand, the previous migration literature identifies a positive connection between perceived social support and both the sense of belonging (Brunsting et al., 2021) and social engagement (Maluenda-Albornoz et al., 2022) in a new environment. The pleasant and favorable social relations and climate generate positive affections about the host communities, resulting in a higher sense of belonging and increased participation in social activities (Brunsting et al., 2021; Wise et al., 2018). Perceived support from close ties serves as a psychological bridge for migrants, boosting their confidence in solving relocation-related problems. This, in turn, fosters a positive outlook toward the future and a feeling of belonging to the local community (Ho et al., 2014). In addition, feelings of being supported can enhance self-esteem and diminish loneliness, facilitating new migrants to adjust to their new roles in the host society (Brunsting et al., 2021).

However, the Stress-buffering hypothesis remains untested to explain the social integration of older cohorts against the backdrop of migration and digital communication technologies. Notwithstanding, existing literature has established that perceived social support plays a mediating role in the positive association between social media usage and psychological well-being (Yue et al., 2023), quality of life (Nam, 2021), as well as the negative correlation with acculturative stress (Li and Peng, 2019) and older adults’ loneliness (Rosen et al., 2022). When it comes to migrants, ample evidence has shown that digitally mediated communication facilitates convenient channels for immigrants to stay in touch with distant family and friends, who lend emotional support as they actively engage with mainstream communities (Baldassar and Wilding, 2020; Croucher and Rahmani, 2015; Wilding et al., 2022). In addition, with the features of building online profiles and asynchronous impression management (e.g., liking, commenting, re-posting), social media applications might help migrants initiate latent ties with neighbors and peers in the host community. The preliminary exchanges online may establish a foundation for further in-person interactions. As such, social media apps serve as social lubricants, promoting mutual comprehension between immigrants and native inhabitants and diminishing uncertainty and ambiguity. This process might foster a sense of security and belonging for the new arrivals (Li and Peng, 2019). Thus:

H6: Social media engagement will positively influence older migrants’ perceived social support.

H7: The degree of older migrants’ perceived social support will positively influence their social integration.

H8: The relationship between social media engagement and social integration is mediated by perceived social support.

Social media usage, psychological resilience, and social integration

Psychological resilience is developed to explain why certain individuals are able to effectively manage and adapt to stressful situations, maintaining steady progress and even achieving personal growth in the process (Fletcher and Sarkar, 2013). It pertains to the individual characteristics that empower someone to flourish when confronted with challenges or difficulties (Connor and Davidson, 2003). Psychological resilience, within the context of migration, refers to the dynamic process through which migrants effectively and successfully navigate and overcome the stressors associated with adjusting to a new culture, integrating into a new community, and cultivating a sense of belonging across diverse cultures (Fu Keung Wong and Song, 2008).

In the resettlement process, the importance of social media usage to newcomers’ psychological resilience is subsequently validated by several studies (Ju et al., 2023; Merisalo and Jauhiainen, 2021; Postolea and Bodea, 2021; Jurgens and Helsloot, 2018). Social media connections are a digital resilience source of emotional support from their distant families and friends, enabling them to feel socially accompanied and access solutions to problems (Udwan et al., 2020). Scrolling interesting content can defuse negative emotions and allow them to maintain a balanced mindset under stressful situations (Ju et al., 2023). Furthermore, social media platforms can empower disadvantaged migrants by providing multiple updated information about remote families and friends, new events of the outside world, and local social services (Udwan et al., 2020). This is beneficial in minimizing cognitive disparities and helping them make sense of their circumstances in unfamiliar surroundings (Jurgens and Helsloot, 2018).

Besides, the significant relationship between psychological resilience and migrants’ social integration is well documented (Wang et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2022; Caqueo-Urizar et al., 2021; Wq and Lw, 2003). Disadvantaged migrants with resilient qualities, such as strong self-esteem, self-acceptance, and self-efficacy, can effectively accomplish their reciprocal adaptation between individual competence and the environment (Huang et al., 2022). An optimistic perspective on life is an internal power that enables newcomers to view challenges in a positive light and actively participate in social activities and interpersonal relationships in new environments (Wq and Lw, 2003; Kim et al., 2023). Therefore, this resilient nature is advantageous for cultivating solid connections in both familial and community settings, facilitating the development of a sense of belonging and a new identity(Caqueo-Urizar et al., 2021; Wq and Lw, 2003).

Although psychological resilience is extensively used in the migration field, it remains unclear whether and how intrinsic personal resources may explain the influence of social media engagement on older migrants’ social integration. Notwithstanding, the inclusion of this notion in the mechanism is consistent with the psychology literature that underscores the significant role psychological resilience plays between social media use and subjective well-being (Chen et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023). In specific, using social media can bridge the gap in offline social networks for socially or economically disadvantaged groups. The emotional support, novel information, and material assistance they receive through online activities can enable them to regain control over their lives. As a result, their level of self-efficacy and psychological resilience gradually rises over time, which is crucial to buffer against poor mental health (Wang et al., 2023). In addition, more resilient new settlers have been shown to acquire more access to social resources and a favorable social environment, which will foster their rapid acclimation and stronger affectional bonds with their new surroundings (Huang et al., 2022). Therefore:

H9: Social media engagement is positively related to psychological resilience.

H10: Psychological resilience is positively related to social integration.

H11: The relationship between social media engagement and social integration is mediated by psychological resilience.

The sequential mediation of perceived social support and psychological resilience

Considerable empirical studies have established the direct effect of perceived social support on the psychological resilience of older adults (Kong et al., 2021) and migrants (Liang et al., 2019). Individuals who perceive greater support from their social networks are more likely to possess higher levels of self-confidence and self-esteem. Consequently, they are more inclined to maintain a positive outlook in the face of adversity and employ efficient coping strategies, leading to a smoother transition through stressful situations (Wang et al., 2023). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that psychological resilience contributes to the adverse influence of perceived social support on depression among rural-to-urban migrants, as well as the beneficial effect on the health efficacy of elderly migrants (Liang et al., 2019). In addition, Huang et al. (2022) have validated the path of “social capital-resilience-social integration” among migrant children, suggesting the importance of drawing resources from reciprocal interactions with various social connections on the personal growth of migrants. As such, it is plausible that older migrants’ perceived social support through social media engagement buffers against poor social integration by boosting psychological resilience.

H12: Perceived social support is positively related to psychological resilience.

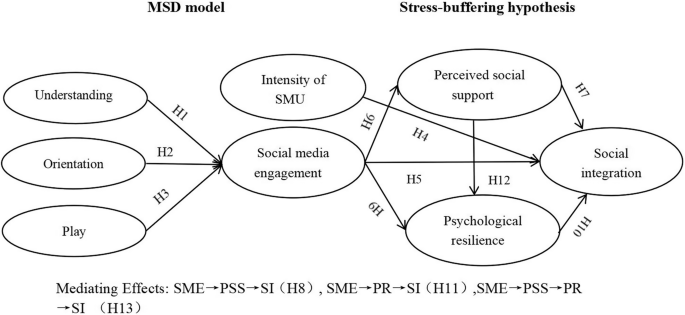

H13: Social integration may predict older migrants’ social integration through the sequential mediating effect of perceived social support and psychological resilience. Figure 1 shows the conceptual model.

A representation of the relationship between all the variables used (understanding, orientation, play, intensity of social media use, social media engagement, perceived social support, psychological resilience, and social integration). Here, the intensity of social media use is a single-item construct; understanding, orientation, play, psychological resilience, and social integration are lower-order constructs; and social media engagement and perceived social support are higher-order constructs.

Methodology

Data collection and samples

This study employed the quantitative research design with an online survey. The questionnaire consists of four sections: filtering questions, demographic information, frequency of use of various social media apps, and measurement scales of the constructs. The population of this study is “older migrants” in mainland China. They have relocated to urban areas for over six months to provide care for their grandkids or for retirement purposes. Additionally, they have been using social media applications in their daily lives for more than two months. The age range of this population is 55 years and above. This age range is set according to the Boston Consulting Center’s report titled “China’s Digital Generation 3.0: The Online Kingdom” (Michael et al., 2012), which defines older Internet users as those 55 and older. This setting of age for trailing parents was also adopted by several other relevant studies (Dou and Liu, 2017; Xu et al., 2021).

Eligible respondents in this study retain hukou in their original homelands, who are not permanent migrants but rather an invisible floating population traveling to and from two places. Thus, the official data only reveals the older floating population nationwide without breaking down the purposes of mobility. Given these practical considerations, this study adopted the non-probabilistic approach of online convenience sampling through the Tencent Questionnaire, one of the most popular online survey platforms in China, to gather a sample from this geographically scattered population economically and efficiently.

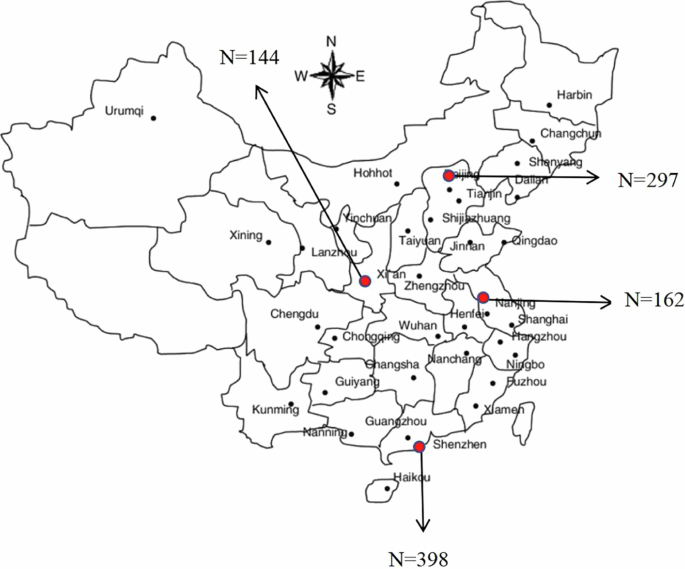

A cross-sectional online survey was conducted in four conveniently selected large Chinese cities from June 20 to July 15, 2023. These cities comprise Beijing in the north with a floating population of 8.2 million, Xi’an in the west with a floating population of 3.747 million, Nanjing in the east with a floating population of 4.41 million, and Shenzhen in the south with a floating population of 11.73 million (CNBS, 2023). Beijing is the capital of China, Shenzhen is the country’s leading special economic zone adjacent to Hong Kong; Xi’an and Nanjing are the capitals of their provinces. As major economic engines in their respective regions, they all have a sizeable floating population, which can provide sufficient and satisfactory samples for this study. After setting up each geographic location, the researcher selected “older group aged 55 and over” and “urban areas” on the sample setting page separately for each city.

Tencent Questionnaire then randomly sent a link to the questionnaire to the eligible social media users in its sample panel through popular social media platforms such as WeChat, QQ, or Douyin. Participants who were provided with information about the research objectives and willingly agreed to participate were required to respond to four screening questions, including (1) “Have you left your hometown where you have lived for many years for more than half a year?” (2)“Did you follow your adult children to live here?” (3)“Did you migrate to this new place to care for your grandchildren or retire with families?” and (4) “Do you use social media, such as WeChat, TikTok (Douyin in Chinese), Kuaishou, Tencent QQ, and so on, in your daily life for more than two months?”. Those who gave four answers of “yes” were able to proceed to the formal survey stage. To ensure that the respondents comprehend and thoroughly answer all the questions within an adequate timeframe, only those responses with a total answer duration exceeding one minute were included in the sample for this study.

Finally, 1001 usable questionnaires (37 deleted for data entry errors, 21 for outliers) were collected. Out of the 1001 valid responses, Beijing has a total of 297, Xi’an has 144, Shenzhen has 398, and Nanjing has 162. Data collected in each city exceeds the minimum sample size of 85 established by the G power analysis with 0.15 effect size at 80% power level and predictors number of 4. The geographic context of this study is shown in Fig. 2. In our sample shown in Table 1, the proportion of women (55.8%) is slightly higher than men (44.2%); the majority of participants are younger elderly aged 55–64 (81.8%); the vast majority of respondents, at 88.5%, are married. Overall, participants have a moderate level of education, with 60% completing middle to high school education. The vast majority of them are not new migrants, with close to 90% having migrated for more than a year and over 50% for more than three years. As for sources of income, 71.5% of respondents have a pension, which indicates that most are financially independent.

This figure shows a map of China with 35 major cities, highlighting the positions and sample sizes of the four cities selected for this research. Source: Li (2013).

Data analysis methods

SPSS 27 is applied to perform descriptive statistical analysis. Subsequently, the predictive power of the measurement model, as well as the associations between all the constructs, are examined by Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). SEM-PLS has been a popular statistical technique in the fields of urban migration (Gheitarani et al., 2020; MeiRun et al., 2018) and information technology adoption (Ilias et al., 2022; Yaseen and Al Omoush, 2020). We chose PLS-SEM due to its several advantages over CB-SEM. As a prediction-oriented method, PLS-SEM is more suitable for theory development, which is the purpose of this study (Afthanorhan et al., 2021). Additionally, it is the most suitable approach for developing and estimating the causal relationships of a complex structural model with higher-order and formative constructs (Hair et al., 2017). Besides, our data were distributed non-normally, which is more appropriate for analysis by PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 2017).

Measurement scales

The measurement tools and scales used in this study were derived from established literature to ensure the reliability and validity of the data analysis results. Instead of standardizing all scales to the same format, we followed the original formats in terms of the number of response categories (5- and 7-point scales). Korkut Altuna and Arslan (2016) proved that there are no statistically significant differences in the results (e.g., internal structure, mean, and standard deviation) obtained using 5- and 7-point versions of the scale of the same variable. However, Podsakoff et al. (2003) suggested that providing respondents with varied scale formats in the questionnaire can minimize method bias due to the consistency of scale properties. A uniform scale format can make it too easy for respondents to complete the questionnaire with a lack of cognitive and reflective processing. Thus, more response categories enable researchers to gather more reliable and valid data, resulting in more robust statistical outcomes (Alwin, 1997).

Social media dependencies

The measurement for three distinct social media dependencies is adapted from Carillo et al. (2017). Respondents are asked to rate three 5-point Likert sub-scales with 1 indicating strongly disagree and 5 indicating strongly agree on six items for understanding (M = 3.79, SD = 0.678, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.817), six for orientation (M = 3.73, SD = 0.65, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.805), and six for play (M = 3.85, SD = 0.647, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.805).

Intensity of social media use was assessed using Zhao et al. (2021b) measurement of Chinese trailing parents social media use. Participants are asked one single item: how often do you use social media applications such as WeChat, Douyin, or QQ in your daily life? (1 = Not at all, 2 = Less than once a week, 3 = About once each week, 4 = Several times each week, 5 = About once each day, 6 = several times a day, 7 = The whole time a day) (M = 5.48, SD = 1.468).

Social media engagement was treated as a reflective-reflective higher-order construct (HOC), the measurement of which was derived from Wei and Gao (2017). It was categorized into three dimensions: 4-item information production (M = 2.72, SD = 0.883, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.792), 4-item information retrieval (M = 3.3, SD = 0.799, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.700), and 5-item social activities (M = 2.71, SD = 0.812, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.739). Responses are recorded on a 5-point rating scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = occasionally, 4 = often, 5 = very frequently) (M = 2.91, SD = 0.709, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.759).

Perceived social support was regarded as a reflective-formative higher-order construct (HOC) and assessed using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) developed by Zimet et al. (1990). This scale comprises three 4-item sub-scales (i.e., significant other, family, friends) with good reliability and validity. Each item was rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from very strongly disagree (1) to very strongly agree (7). In addition, one global single item was created to estimate the convergent validity of this HOC. (Significant other: M = 4.87, SD = 1.221, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.895; family: M = 5.37, SD = 1.138, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.887; friends: M = 5.13, SD = 1.11, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.877)

Psychological resilience was measured employing the 10-item scale of resilience developed by Campbell-Sills and Stein (2007) to refine the 25-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) (Connor and Davidson, 2003). All items carry a 7-point range of responses from very strongly disagree to very strongly agree (M = 4.95, SD = 1.054, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.929).

Social integration was assessed by applying the 4-item scale developed by Wei and Gao (2017) to measure the social integration of Chinese urban migrants. Each item is assessed on a 5-point Likert-type scale with responses of strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) (M = 3.67, SD = 0.727, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.819).

The established scales were modified to be culturally adapted to the specific situations of elderly migrants in China. Since all these scales were drawn from the English literature, the researchers employed back-translation to guarantee that the translated versions grasped the content of the source items and were easily understood by older migrants. Before formally distributing the online questionnaire, we carried out a pre-test with six potential respondents to gather feedback and suggestions regarding the content, format, and design of the survey (Drennan, 2003). We then revised the questionnaire until all six participants were able to fully comprehend the purpose of each question and provide their answers without difficulty.

Data analysis

Common method bias

Before performing PLS analysis, it is necessary to test the extent of bias caused by common method variance (Richardson et al., 2009). Harman’s single factor test shows that the total variance extracted from a single factor is 30.74%, less than 50%. Besides, the full collinearity test relating a random manufactured variable to all variables in the structural model yields VIF values between 1.106 and 1.949, below 3.3 (Hair et al., 2017). Thus, there is no common method bias issue in our data.

Measurement model evaluation

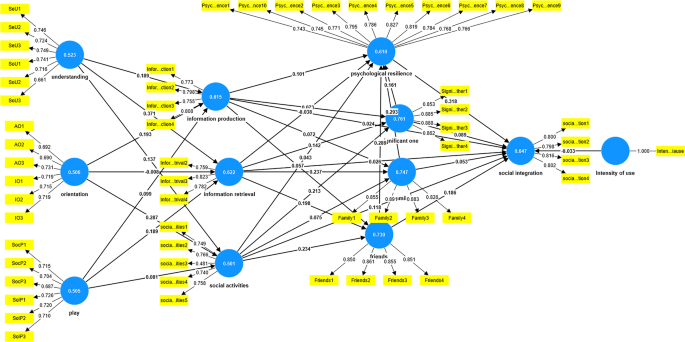

Assessing the measurement model, this study evaluated construct reliability using composite reliability (CR) and convergent validity. As demonstrated in Table 2, the CR for all constructs exceeded 0.8, higher than the threshold of 0.7 (Hair et al., 2017). Moreover, the outer loadings of the items and the average variance extracted for the constructs exceeded 0.7 and 0.5, respectively, proving qualified convergent validity. Most of the items and constructs in Table 2 showed satisfactory outer loadings and AVE values, except for SA3 and IR1, with outer loadings between 0.4 and 0.7; IR1 was deleted for its removal being able to raise Cronbach’s alpha of IR to 0.7.

Finally, Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) criterion was applied to assess the discriminant validity among the constructs. Table 3 shows that the HTMT scores for most of the constructs are below the threshold of 0. 85 or 0.9, suggesting acceptable discriminant validity. Figure 3 illustrates the results of the Smart PLS algorithm for the lower-order reflective measurement model.

Higher-order constructs (HOC)

In current research, social media engagement and perceived social support are reflective-reflective and reflective-formative HOC, respectively. HOC, or the hierarchical component model, refers to a framework where an abstract construct is developed with its corresponding concrete sub-dimensions (Sarstedt et al., 2019). Higher-order constructs are developed to reduce the number of relationships (hypotheses needed to be tested) in the structural model, resulting in a more concise and comprehensible PLS path model (Hair et al., 2017). Moreover, HOC enables the researcher to attain an equilibrium between the diversity and thoroughness of the information acquired from the path model assessment (Sarstedt et al., 2019).

The disjoint two-stage approach was employed to assess the reliability and validity of HOCs (Sarstedt et al., 2019). Evaluating the initial measurement model, the researcher directly connects lower-order components of higher-order constructs to the other constructs theoretically associated with the HOCs. In the second stage, the preserved latent scores of lower-order constructs are used to measure HOCs linked with all other constructs in the path model for further measurement model estimation. Resultantly, as shown in Table 4, the CR, convergent validity (outer loading and AVE), and HTMT scores in Table 5 of social media engagement are all above the acceptable values, proving satisfactory reliability and validity. For perceived social support demonstrated in Table 6, redundancy analysis was first conducted to assess its convergent validity, showing that the path coefficient for the HOC related to the global single item was 0.755, above the threshold value of 0.7. Next, multicollinearity was proved to be not present through VIF values below 3.3 (between 1.900 and 2.197). Lastly, the outer weights of all lower-order constructs are significant at less than 0.001, further validating the HOC of perceived social support.

Structural model assessment

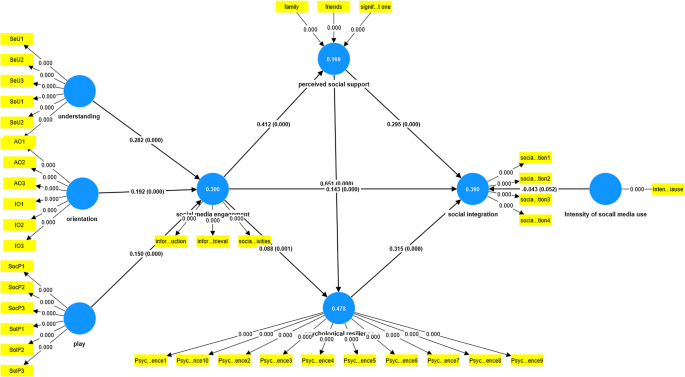

After validating the measurement model comes the evaluation of the structural model. Firstly, the inner VIF values for all the constructs are between 1 to 2.417, lower than the cut-off value of 3.3 (Hair et al., 2017), indicating no co-linearity issue in our data. Next, bootstrapping with 5000 sub-samples was applied to test the hypotheses of direct relationships (Table 7). The significant paths relating to understanding (β = 0.282, p < 0.001), orientation (β = 0.192, p < 0.001), and play (β = 0.150, p < 0.001) dependencies on social media engagement support H1, H2, and H3. The results showed that the path coefficients of social media engagement (β = 0.143, p < 0.001) and intensity of social media use (β = −0.043, p = 0.052) on social integration are significant and insignificant respectively, supporting H4 but not H5. The path coefficients pertaining to social media engagement on perceived social support (β = 0.412, p < 0.001) and psychological resilience (β = 0.088, p = 0.001) indicate a significant and positive relationship, proving empirical support for H6 and H9. The results also suggested that H7 and H10, which concern the effect of PSS (β = 0.295, p < 0.001) and PR (β = 0.315, p < 0.001) on SI are supported. Finally, the results confirm that PSS positively and significantly influences PR (β = 0.651, p < 0.001). Overall, as shown in Table 8, this structural model explains 30% of the variance in SME, 16.9% in PSS, 47.8% in PR, and 39% in SI, establishing sufficient explanatory power.

In terms of the effect size (f2) values (Table 7), the relationships of play with SME (0.015), SME with PR (0.012), and intensity of use with SI (0.003) where f2 is less than the threshold of 0.02, indicating none effect size. Understanding (0.061) and orientation (0.022) dependencies possess small yet significant effect sizes in generating R2 for SME. While SME (0.204) has a moderate effect on PSS (0.674), which shows a substantial effect on PR. SME, PSS, and PR possess small but significant effects in explaining SI. Lastly, the Q2 values for SME (0.198), PSS (0.123), PR (0.288), and SI (0.245) confirm the model’s predictive capability on endogenous variables (Table 8).

Mediating effects of perceived social support and psychological resilience

Three mediation effects were assessed to test H8, H11, and H13. The results in Table 9 show that the indirect effect of “SEM → PSS → SI” was 47% of the total effect, indicating a significant partially mediating effect and supporting H8. Although significant, the mediating effect of PR between SME and SI hypothesized in H11 only accounts for 17.4% of the total effect, lower than the 20% threshold (Hair et al., 2017), failing to be valid. Finally, the chain mediating effect of “SEM → PSS → PR → SI” hypothesized in H13 can explain 39% of the total effect, suggesting a significant partial mediation. Figure 4 illustrates the PLS-SEM results of the structural model.

Discussion

Discussion of findings

The focus of this research, trailing parents, arises due to the prevailing pattern of family migration and the escalating aging population in China. They are experiencing the dilemma of social integration into new communities. Given the rapid popularization of social media use among the elderly in China, this study investigated the impact of social media engagement of trailing parents on their social integration and its underlying psychological mechanism.

From an individual-media relationship perspective, our findings indicate that three social media dependencies all had significant effects on older migrants’ social media engagement. These results align with previous relevant literature (Chiu and Huang, 2015; Kim and Jung, 2017; Yang et al., 2015). Among the factors affecting older migrants, understanding has the greatest impact, followed by the need for orientation. The role of play, on the other hand, has a minor effect, as indicated by its extremely small effect size. As older migrants navigate drastic changes in their environments, they often struggle to adapt their existing life experiences and social capital to new urban settings. This difficulty can heighten their susceptibility to feelings of threat and uncertainty. As a result, they rely more on social media as indispensable platforms for gathering information, which allows them to gain insights into new living environments and personal circumstances. Additionally, social media provides them with behavioral and interactive guidance on how to adjust to new lifestyles and expand their social networks.

The current study validates that social media engagement can foster social integration among older migrants. Thus, this study adds new empirical evidence for the established association between social media use and migrants’ social integration (Wei and Gao, 2017; Zhao et al., 2021a; Zhao, 2023). However, the intensity of social media use does not impact their degree of integration into the local community. That is to say, in contrast to the exposure condition of social media, the extent of selective exposure cannot predict the social integration of older migrants. This result may be attributed to the fact that over-reliance on social media will deprive users of opportunities to participate in local communities and develop offline connections (Lim and Pham, 2016). The extensive social connections formed through social media platforms do not necessarily result in meaningful social interactions and, as a result, do not definitively foster social integration (Yoo and Jeong, 2017). As such, it is the quality of media exposure, manifested in active and attentional engagement in diversified online activities, that can enhance social integration among trailing parents.

Furthermore, this research validates that social media engagement is beneficial for improving older migrants’ perceived social support, with a moderate effect size. It confirms the work of Mikal et al. (2013), indicating that social media offers a means to strengthen existing connections and build new weak ones for those who are vulnerable in terms of support availability. Given the dialect diversity across regions of China, social media apps like WeChat, with their video and text messaging features, become invaluable for older migrants who lack fluency in Mandarin. These apps enable them to communicate more effectively with locals and broaden their social networks (Pang, 2018). Meanwhile, keeping in touch with distant families and friends through social media allows older migrants to feel emotionally nourished by digital kinning (Baldassar and Wilding, 2020). Furthermore, the present results underscore the significant effect of perceived social support to improve social integration for trailing parents, echoing the increasing advocacy for the relevance of strengthening social networks and social capital to social integration among older migrants (Zhao et al., 2021a; Zhao, 2023).

Moreover, the present study adds new empirical evidence for the mediating impact of perceived social support, lending support to the stress-buffering mechanism of social support. According to this hypothesis, the relevance of perceived social support for older migrants stems from its power to promote favorable cognitive appraisal of the integration difficulties (Cohen and Wills, 1985). In the context of digital-mediated communication, social media engagement addresses the constraints posed by limited physical mobility and dialect barriers, fostering a subjective belief about the availability of supportive resources from family, friends, and local acquaintances. The acquired social closeness and emotional strength, in turn, can boost their confidence in dealing with obstacles in unfamiliar surroundings and increase their willingness to engage in offline social activities (Ashida and Heaney, 2008). Moreover, the perceived supportive and pleasant social environment can contribute to their feeling of belonging to the host community.

On the other hand, the limited effect of social media engagement on psychological resilience, with a minimal effect size, runs counter to prior research that suggests the beneficial impact of digital communication technologies on migrants’ resilience (Ju et al., 2023; Udwan et al., 2020). This means that social media engagement has little practical relevance in increasing resilience among trailing parents. One possible explanation could be that online activities often fall short of replicating the benefits of offline face-to-face interactions. It can lead to social comparison and anxiety without addressing real-life problems, thereby hampering the cultivation of positive emotions and resilient behavior in the face of adversity (Boonlue et al., 2016). Thus, it is plausible that social media engagement hardly makes older migrants substantially more resilient. Additionally, our findings indicate that older migrants who possess greater psychological resilience are more likely to be socially integrated. This result offers support to the buffering role of internal resources against migrants’ maladjustment to new environments (Huang et al., 2022). To put it simply, trailing parents are confirmed to exhibit a pattern of “disadvantageous-resilience-good adaptation” as suggested by Zeng (2010).

However, the results fail to establish the mediating role of psychological resilience between social media engagement and social integration among older migrants. The main reason may derive from the fact that simple social media use to promote their psychological resilience is insufficient. Previous literature suggested that it is active social participation and content creation on social media that will effectively boost migrants’ psychological resilience (Ju et al., 2023). However, our results demonstrate that trailing parents use social media frequently in their daily lives, but they do not actively engage in actual interactive activities. Instead, they mostly passively consume information rather than actively socialize or create content. Thus, psychological resilience alone is insufficient to account for the positive impact of social media engagement on the social integration of older migrants in practical terms.

Notwithstanding, it is worth noting that this study validates the impact of perceived social support on psychological resilience among older migrants, with a substantial effect size. This chain effect offers support to the resilience framework established by Wang et al. (2023), which indicates that the inner strength of trailing parents is mainly activated by external stimuli, leading to a rapid rejuvenation and proactive approach to resolving the obstacles and complexities associated with integrating into unfamiliar surroundings. Furthermore, our results validate the partially sequential mediation of perceived social support and psychological resilience in the relationship between social media engagement on social integration among trailing parents. This finding can be explained under the lens of reciprocal human-environment interaction (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). The social environment of older migrants comprises distant families and friends, adult children, and local acquaintances. Social media platforms offer compensatory venues for older migrants to sustain and broaden diversified social networks, increasing access to emotional, informational, and material resources. During this process, these silver-haired settlers are energized with the awareness of a supportive social milieu that would evoke an inner strength to effectively deal with daily hassles and significant challenges related to migration in aging (Wang et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022). Social integration occurs when they successfully adjust their personal competence to the external social context.

Theoretical and practical implications

This study has several theoretical implications. It develops and validates a comprehensive model to provide a nuanced understanding of how older migrants who drift to distant and unfamiliar cities as they age utilize social media to foster their integration into host societies. The present study provides a fresh perspective to explain the drivers of trailing parents’ social media use by drawing on the Media system dependency theory to explore the relationship among older migrants, social media, and their external environment. Thus, this study extends the MSD model by testing the effects of three distinct media dependency relations on trailing parents’ social media engagement, providing additional empirical support for the application of this model in the context of migration. In addition, different from the past research that simply assessed social media use behavior in terms of duration or intensity of adoption (Zhao et al., 2021a; Zhao, 2023), this study presents greater measurement reliability by verifying the different effects of trailing parents’ selective exposure and exposure condition of social media on their social integration.

Another key contribution of this study is to provide some preliminary insights into the psychological mechanisms underlying the relationship between older migrants’ social media engagement and social integration, an under-researched area in the existing literature. Our study echoes the increasing advocacy for perceived social support as a critical external buffer against social integration stress among older migrants. Thus, this study offers empirical support for applying the Stress-buffer hypothesis in the intersectional context of digital communication and urban migration. More importantly, previous studies have failed to consider internal protective forces, and the present study addresses this gap by investigating psychological resilience as a critical indicator of psychological mechanisms. The direct effect of social media engagement on psychological resilience without practical significance diverges from prior research on the positive impact of SNSs on improving immigrants’ inner strength (Ju et al., 2023; Udwan et al., 2020). Based on this, our study reflects on the importance of the diversity and proactivity of social media use behaviors in improving older migrants’ resilience. Furthermore, our study establishes a sequential mediation of perceived social support and psychological resilience, developing a novel theoretical framework for explaining the influence of social media engagement on social integration from a psychological perspective.

Practically, the results demonstrate that social media engagement is advantageous for enhancing the social integration of trailing parents. Their main motivations for engaging in social media activities are primarily understanding, followed by orientation, and lastly, entertainment. Therefore, it is advisable for app developers to streamline the interaction and content generation features to make them more easily understood and accepted by older adults. This will enable them to transition from passive recipients of information to active participants. Meanwhile, social media apps like Douyin and WeChat should enhance the delivery of content relevant to older users, focusing on intellectual, practical, and social subjects. Additionally, it is vital to strengthen the monitoring of false information and rumors to prevent any misleading content. Besides, our findings suggest that social media engagement enables older migrants to perceive greater social support, leading to higher psychological resilience and, ultimately, a better sense of integration and belonging to the local society. Community workers should use social media platforms to organize floating seniors scattered in communities, enabling them to participate in various community activities and receive practical information related to local community life, thereby improving their local social support and sense of belonging to the local community. In addition, it is imperative for adult children to assist their parents in bridging the digital divide and seamlessly integrating into the realm of digital communication. Specifically, adult children should assist their parents in enhancing their proficiency in utilizing social media apps and expanding their variety of social media engagements.

Limitations and future research

There are some limitations of this study. First, the cross-sectional approach cannot examine causal relationships between the variables. As such, future research should test the causal direction using a longitudinal survey, such as collecting data on motivations in Stage 1, social media engagement in Stage 2, psychological mechanisms in Stage 3, and social integration in Stage 4. Second, online convenience sampling used in this study tends to yield homogenous data, making it difficult to generalize the results. Future studies should use probability sampling via face-to-face surveys to mitigate representative bias in the data. Thirdly, this study treated social media engagement and social integration as two generalized constructs, suggesting that future research should examine distinct social media activities and various dimensions of social integration (e.g., cultural-social, economic, and psychological) separately. Fourth, since three social media dependencies only generate a limited variance in social media engagement, hence, so future research should explore other drivers, such as psychological, familial relationships, and socio-environmental factors. Finally, this study validated the partially mediating role of perceived social support and its partially chained mediation with psychological resilience. Thus, future studies should explore other mediators to refine older migrants’ psychological processes from social media engagement to social integration.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study theoretically validate the applicability of the Media system dependency theory and the Stress-buffering hypothesis within the framework of the confluence between urban migration and digital communication technologies. In addition, our study broadens the horizon of understanding the social media effectiveness on older migrants’ social integration from the perspective of the transformation of psychological experiences. Moreover, the results of this study provide strategic guidance for app developers, community workers, and adult children. The main findings of this investigation can be succinctly laid out as follows.

Understanding and orientation are the key determinants driving older migrants’ social media engagement. Contrary to younger users who regard social media as digital spaces for entertainment, older migrants generally utilize social media as a means to get behavioral and social guidance to comprehend and adjust to unfamiliar cultural and social surroundings. In addition, the exposure condition of social media is beneficial in improving the social integration of older migrants, but the intensity of social media use is not equally effective. Thus, trailing parents are encouraged to promote the quality of their social media usage by engaging actively in diversified online activities to strengthen social and affectional bonds with the local community.

The primary psychological impact of engaging with social media for older migrants is the boost in self-assurance to access the essential social resources crucial for their integration into local communities. Online social networking helps trailing parents who lack offline social support overcome challenges by evoking positive cognitive adjustments. This, in turn, encourages them to adopt more proactive strategies of integration. However, the effect of social media engagement on improving psychological resilience is limited, which hinders the process of integrating older migrants into mainstream society by taking advantage of digital communication technologies. Therefore, this study suggests app developers streamline the layout and functionalities to enhance the user-friendliness of social media platforms for elderly migrants with poor digital proficiency. By improving their interaction and creativity on social media, disadvantageous trailing parents are likely to evolve with improved personal competence and mindfulness, thriving on integration dilemmas.

Furthermore, our study posits that in the context of the increasing prevalence of social media as the primary information system depended on by older users, the key psychological path toward social integration among older migrants can be summarized as “disadvantageous-perceived social support-resilience-desirable integration”. In other words, social media engagement reinforces the bidirectional interaction between older migrants and their social environments, lifting their confidence and hope by developing a pleasant social atmosphere. The external spiritual strength, in turn, serves as a catalyst for their personal growth, enabling them to become more resilient and equipped to integrate into the host environments in spite of various obstacles. Thus, community workers are suggested to gather and mobilize dispersed and hidden older migrants through social media to help them activate latent local ties. For adult children, it is imperative to encourage their parents to actively engage in various social media activities and offer them technical support.

Data availability

The data obtained in this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements with the participants but can be accessed by the corresponding author due to justifiable reasons.

References

-

Adachi S (2011) Social integration in post-multiculturalism: an analysis of social integration policy in post-war Britain: social integration in post-multiculturalism. Int J Jpn Sociol 20(1):107–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6781.2011.01155.x

-

Afthanorhan A, Ghazali PL, Rashid N (2021) Discriminant validity: a comparison of CBSEM and consistent PLS using Fornell & Larcker and HTMT approaches. J Phys Conf Ser 1874(1):012085. IOP Publishing

-

Aichner T, Grünfelder M, Maurer O, Jegeni D (2021) Twenty-five years of social media: a review of social media applications and definitions from 1994 to 2019. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 24(4):215–222. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0134

-

Alwin D F (1997) Feeling thermometers versus 7-point scales: Which are better? Sociol Methods Res 25(2):318–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124197025003003

-

Ashida S, Heaney CA (2008) Social networks and participation in social activities at a new senior center: reaching out to older adults who could benefit the most. Activ Adapt Aging 32(1):40–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924780802039261

-

Baldassar L, Wilding R (2020) Migration, aging, and digital kinning: the role of distant care support networks in experiences of aging well. Gerontologist 60(2):313–321. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz156

-

Ball-Rokeach SJ (1985) The origins of individual media-system dependency: a sociological framework. Commun Res 12(4):485–510. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365085012004003

-

Berner J (2014) Psychosocial, socio-demographic and health determinants in information communication technology use by older adults. Dissertation, Blekinge Institute of Technology

-

Boonlue T, Briggs P, Sillence E (2016) Self-compassion, psychological resilience and social media use in Thai students. Paper presented at Proceedings of the 30th International BCS Human Computer Interaction Conference. BCS Learning & Development. July 2016 https://doi.org/10.14236/ewic/HCI2016.4

-

Brandhorst R (2023) Older Vietnamese refugees’ transnational digital social capital and its impact on social inclusion. J Ethn Migr Stud 5(9):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2208738

-

Bronfenbrenner U (1979) The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press Google Schola 2. pp. 139–163

-

Brunsting NC, Zachry C, Liu J, Bryant R, Fang X, Wu S, Luo Z (2021) Sources of perceived social support, social-emotional experiences, and psychological well-being of international students. J Exp Educ 89(1):95–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2019.1639598

-

Bucholtz I (2019) Bridging bonds: Latvian migrants’ interpersonal ties on social networking sites. Media Cult Soc 41(1):104–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718764576

-

Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB (2007) Psychometric analysis and refinement of the connor–davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress 20(6):1019–1028. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20271

-

Caqueo-Urizar A, Urzua A, Escobar-Soler C, Flores J, Mena-Chamorro P, Villalonga-Olives E (2021) Effects of resilience and acculturation stress on integration and social competence of migrant children and adolescents in Northern Chile. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(4):2156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042156

-

Carillo K, Scornavacca E, Za S (2017) The role of media dependency in predicting continuance intention to use ubiquitous media systems. Inf Manag 54(3):317–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.09.002

-

Chen S, Li H, Pang L, Wen D (2023) The relationship between social media use and negative emotions among Chinese medical college students: the mediating role of fear of missing out and the moderating role of resilience. Psychol Res Behav Manag 12(31):2755–2766

-

China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC) (2014, July 21) The 34th Statistical Report on Internet Development in China. Retrieved from https://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2022/0401/c88-765.html

-

China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC) (2023, August 28) The 52th Statistical Report on Internet Development in China. Retrieved from https://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2023/0828/c88-10829.html

-

China National Bureau of Statistics (CNBS) (2011, May 15) Sixth National Population Census Bulletin. Retrieved from http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/indexch.htm

-

China National Bureau of Statistics (2023, February 15) China Population and Employment Statistics Yearbook-2021. Retrieved from http://www.stats.gov.cn/zs/tjwh/tjkw/tjzl/202302/t20230215_1908006.html?eqid=99898fa30003716a000000036489877e

-

Chiu C-M, Huang H-Y (2015) Examining the antecedents of user gratification and its effects on individuals’ social network services usage: The moderating role of habit. Eur J Inf Syst 24(4):411–430. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2014.9

-

Chiu C-M, Huang H-Y, Cheng H-L, Hsu JS-C (2019) Driving individuals’ citizenship behaviors in virtual communities through attachment. Internet Res 29(4):870–899. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-07-2017-0284

-

Cohen S, Wills TA (1985) Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 98(2):310

-

Connor KM, Davidson JRT (2003) Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression Anxiety 18(2):76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113

-

Croucher SM, Rahmani D (2015) A longitudinal test of the effects of facebook on cultural adaptation. J Int Intercult Commun 8(4):330–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2015.1087093

-

Dou X, Liu Y (2017) Elderly migration in China: types, patterns, and determinants. J Appl Gerontol 36(6):751–771. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464815587966

-

Drennan J (2003) Cognitive interviewing: verbal data in the design and pretesting of questionnaires. J Adv Nurs 42(1):57–63. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02579.x

-

Eagle DE, Hybels CF, Proeschold-Bell RJ (2019) Perceived social support, received social support, and depression among clergy. J Soc Personal Relatsh 36(7):2055–2073. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407518776134

-

Fletcher D, Sarkar M (2013) Psychological resilience: a review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur Psychol 18(1):12–23. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

-

Forbush E, Foucault-Welles B (2016) Social media use and adaptation among Chinese students beginning to study in the United States. Int J Intercult Relat 50:1–12

-

Fu Keung Wong D, Song HX (2008) The resilience of migrant workers in Shanghai China: the roles of migration stress and meaning of migration. Int J Soc Psychiatry 54(2):131–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764007083877

-

Fu L, Xie Y (2021) The effects of social media use on the health of older adults: an empirical analysis based on 2017 Chinese general social survey. Healthcare 9(9):1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9091143

-

Gheitarani N, El-Sayed S, Cloutier S, Budruk M, Gibbons L, Khanian M (2020) Investigating the mechanism of place and community impact on quality of life of rural-urban migrants. Int J Community Well-Being 3(1):21–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42413-019-00052-8

-

Glasgow N, Brown DL (2006) Social integration among older in-migrants in nonmetropolitan retirement destination counties: Establishing new ties. In: Population change and rural society. Vol. 16. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht. pp. 177–196

-

Gong J, Zanuddin H, Hou W, Xu J (2022) Media attention, dependency, self-efficacy, and prosocial behaviors during the outbreak of COVID-19: a constructive journalism perspective. Glob Media China 7(1):81–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/20594364211021331

-

Grant AE, Guthrie KK, Ball-Rokeach SJ (1991) Television shopping: a media system dependency perspective. Commun Res 18(6):773–798. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365091018006004

-

Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2017) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA

-

Ho WC, Nor LTY, Wu J (2014) Determinants of perceived integration among Chinese migrant mothers living in low-income communities of Hong Kong: implications for social service practitioners. Int Soc Work 57(6):661–675. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872812452175

-

Huang D, Lin W, Luo Y, Liu Y (2022) Social capital, resilience and social integration of Chinese migrant children. J Soc Serv Res 48(2):214–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2021.2005740

-

Ihm J, Hsieh YP (2015) The implications of information and communication technology use for the social well-being of older adults. Inf, Commun Soc 18(10):1123–1138. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1019912

-

Ilias ISHC, Ramli S, Wook M, Hasbullah NA (2022) Factors influencing users’ satisfaction towards image use in social media: A PLS-SEM analysis. Int J Interact Mob Technol 16(15):172–186

-

Jia Q, Li S, Kong F (2022) Association between intergenerational support, social integration, and subjective well-being among migrant elderly following children in Jinan, China. Front Public Health 10:870428. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.870428

-

Jiang Q, Li Y (2018) Factors affecting smartphone dependency among the young in China. Asian J Commun 28(5):508–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2018.1431296

-

Jordan LP, Graham E (2012) Resilience and well‐being among children of migrant parents in south‐east Asia. Child Dev 83(5):1672–1688. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01810.x

-

Ju B, Dai HM, Sandel TL (2023) Resilience and (dis)empowerment: use of social media among female mainland low-skilled workers in Macao during the COVID-19 pandemic. SAGE Open 13(1):215824402311604. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231160480

-

Jun TJ (2020) Social media political information dependency, political participation and the net generation. Dissertation, University of Malaya

-

Jurgens M, Helsloot I (2018) The effect of social media on the dynamics of (self) resilience during disasters: A literature review. J Contingencies Crisis Manag 26(1):79–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12212

-

Kaniasty K, Norris FH (2009) Distinctions that matter: received social support, perceived social support, and social embeddedness after disasters. Ment Health Disasters 2009:175–200

-

Kim J-R, Park S, Lee CD (2023) Relationship between resilience, community participation, and successful aging among older adults in South Korea: mediating role of community participation. J Appl Gerontol 42(11):2233–2241. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648231183772

-

Kim Y-C, Jung J-Y (2017) SNS dependency and interpersonal storytelling: an extension of media system dependency theory. N Media Soc 19(9):1458–1475. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816636611

-

Kim Y-C, Shin E, Cho A, Jung E, Shon K, Shim H (2019) SNS dependency and community engagement in urban neighborhoods: the moderating role of integrated connectedness to a community storytelling network. Commun Res 46(1):7–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215588786

-

Kong L-N, Zhu W-F, Hu P, Yao H-Y (2021) Perceived social support, resilience and health self-efficacy among migrant older adults: a moderated mediation analysis. Geriatr Nurs 42(6):1577–1582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.10.021

-

Korkut Altuna O, Arslan FM (2016) Impact of the number of scale points on data characteristics and respondents’ evaluations: an experimental design approach using 5-point and 7-point likert-type scales. İstanbul Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fak ültesi Derg 55:1–20. https://doi.org/10.17124/iusiyasal.320009

-

Kouvonen A, Kemppainen L, Ketonen E-L, Kemppainen T, Olakivi A, Wrede S (2021) Digital information technology use, self-rated health, and depression: population-based analysis of a survey study on older migrants. J Med Internet Res 23(6):e20988. https://doi.org/10.2196/20988

-

Li J (2013) What causes China’s property boom? Prop Manag 31(1):4–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/02637471311295388

-