As art season continues to unfold, the spotlight on pioneering women in the art industry has never been brighter and stronger. Now front and center, their contriburtions celebrate and champion diversity, the female experience and also amplify underrerpresented voices.

Now, ELLE UK catches up with trailblazers to hear about the importance of it all.

FIND OUT MORE ON ELLE COLLECTIVE

Hannah Watson

Gallery director and Publisher

Hannah Watson’s TJ Boulting is a sanctuary for women artists, thanks to her clear-eyed vision and progressive planning. Nestled in the heart of Fitzrovia – a hub of creativity in London – the gallery occupies two floors of an exemplary art nouveau building, once home to a furnishing ironmonger who now lends his name to the space. Inside, there’s a green-velvet sofa and shelves packed with volumes (independent art-book publisher Trolley Books is also based here). Downstairs is the gallery space: two rooms that are periodically transformed by featured artists. Juno Calypso turned it into an underground garden, and Maisie Cousins once had a gold floor installed. Daisy Collingridge covered the walls with soft, sculpted-jersey versions of viscera and internal organs. For the current group exhibition ‘Un Oeuf is un Oeuf’ (on view until 16 November), the director Hannah Watson invited Sarah Lucas to restage her participatory painting One Thousand Eggs for Women, for which a thousand women came and threw an egg at the wall. (Pullet eggs – laid by young hens and usually rejected by supermarkets – were used to keep it more eco-friendly.)

Outside of exhibitions, the space hosts a plethora of events, including kids’ workshops, daytime raves, pasta-and-movie nights, Lebanese lunches and talks enjoyed from the comfort of beanbags. ‘That’s what I get a kick out of: every show is different,’ Watson says. She founded the gallery in 2012 with the late photographer Gigi Giannuzzi. ‘I love making exhibitions, I love people coming here.’

The director has created a safe space for women creatives in a scene still dominated by men, giving many award-winning artists – Poulomi Basu, Siân Davey, Haley Morris-Cafiero – crucial early-career shows. Katy Hessel curated her first major exhibition here in 2018. Watson has also presented offbeat shows about established figures, such as photographer Lee Miller – the subject of the recent biopic starring Kate Winslet. At the moment, she’s working with musician Viv Albertine, formerly of the Slits.

This year, the gallery is participating in Frieze Sculpture for the first time, with work by Juliana Cerqueira Leite, whom Watson has worked with since she graduated from the Slade in 2006 (Leite’s first solo show was at TJ Boulting). ‘Seeing artists get recognition and being picked up by big galleries, it’s affirming,’ Watson says. ‘It’s hard having to survive by selling work, but you’ve got to keep doing it. Artists need money – everyone needs money! That’s the nature of directing a gallery: you have to balance what you find interesting and exciting with the financial pressure to make it work.’ Certainly, there’s no sense of compromise at the expense of art here. What defines a TJ Boulting artist ‘Intelligent, original, strong voices,’ Watson says. Visit the gallery, and you have to agree.

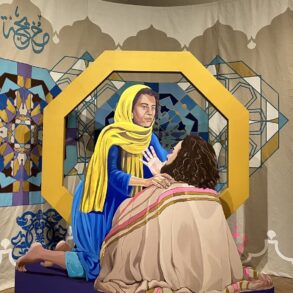

Claudette Johnson

Artist

At a glitzy award ceremony at Tate Britain in December, the winner of one of the best-known prizes in visual arts will be announced, and Claudette Johnson is one of four artists in the running. When she received the Turner Prize nomination – for her solo exhibition ‘Presence’ at the Courtauld Gallery – Johnson said, humbly: ‘I was really surprised but delighted. I had not expected that to happen! It’s a special kind of acknowledgement, and it’s exciting to know the show had an impact, so I’m very happy.’ This year, Johnson was also elected to the Royal Academy of Arts, one of Britain’s most historic and prestigious institutions.

Johnson’s humility belies the magnitude and force of her work, though recognition for those contributions has been more recent. In 1983, while still a student at the University of Wolverhampton, Johnson became a founding member of the Blk Art Group, an

association of Black British artists that included Lubaina Himid, Wenda Leslie and Marlene Smith. Galvanised by anti-racist discourse and feminist critique of the time, the group tackled the representation of Black artists, rewriting their history and importance in Britain. ‘It was such a difficult time, we had to work hard to get together to form a support network that became crucial to our development as artists,’ she says.

Johnson’s figurative paintings and drawings almost exclusively feature Black women, and she captures them with sinewy, silky lines in ink, gouache, pastel and charcoal that soar with emotion. There’s always a feeling of space around her figures, which allows them room for possibilities, the potential to expand out of the image, for the viewer to invent. Many of Johnson’s works take up large amounts of space, too. ‘I have always had some attraction to a certain type of monumentalism in Black figuration – because we have been minor figures, obscured and invisible,’ Johnson says.

Sometimes the most ordinary moments are the most poignant. A giant gouache painting titled Reclining Figure, stretching to more than two metres wide, portrays a woman simply lying down a depiction of tender quiet made massive. It subtly questions who is allowed to rest, and how that rest is perceived.

Johnson’s sitters don’t always have an easy time, not least because the artist sometimes demands difficult poses that give the final portraits their dynamic tension. ‘It takes a lot of trust and almost faith for the sitter to allow me to really see them – to spend that time looking and getting to know their features,’ she says. ‘It’s not an easy experience, meeting who they are, and who I want them to be for the moment.’

Imme Dattenberg-Doyle & Sofia Carreira-Wham

Gallery owners

Imme Dattenberg-Doyle and Sofia Carreira-Wham would meet every Saturday at Victoria station as teenagers, taking the Tube to Green Park for a gallery crawl around Mayfair’s commercial spaces. ‘We didn’t have the money to go to the museum shows, but we were amazed and impressed at what was on offer for free,’ they say. When they left school, the friends knew they wanted to work in culture, but the idea of one day founding their own gallery called Doyle Wham was a private joke. After a few ‘brutal, horrible’ years working for ‘some divas’ in the gallery sector, they decided the only way to fulfil their pipe dream was to go out on a limb and give it a try. In October 2020, Doyle Wham became a reality.

‘Nothing can prepare you for it – you do every single job, and we’re a two-person team,’ the pair say. Four years on and Doyle Wham, housed in a cosy space in Shoreditch, is going from strength to strength. It’s the UK’s first and only gallery dedicated to contemporary African photography, exhibiting a broad range of voices and visions from across the continent: contemporary fashion photography, fine art, documentary and traditional practices, as well as more experimental approaches.

Until 14 December, Doyle Wham is showing the work of groundbreaking, all-female, South Africa-based collective Umseme Uyakhuluma, and coming up in January is British Ghanaian artist and actor Heather Agyepong’s ‘Ego Death’. The team are also working on an Afrobeat exhibition. But, when you show up to the gallery, you are just as likely to find other activities going on: crochet workshops, poetry readings, performances and brunch (with Dattenberg-Doyle’s homemade pastries). ‘We don’t feel welcome in the art market or the art scene – there are galleries we still go to and they never offer you anything, there’s no interaction and it can be alienating,’ they say. ‘We always welcome everyone to our exhibitions. If people who have never been to an exhibition have the opportunity to come and they have a good experience, that’s really meaningful to us. It shouldn’t be radical to talk to the people who come to your gallery!’

Eva Langret

Artistic Director, Frieze

You may remember that achingly chic family who appear briefly in the opening gallery-set scene of rom-com Rye Lane: a cameo by Eva Langret, Frieze’s artistic director, her husband and their young son. Langret is married to director Raine Allen-Miller’s father, Mark Miller. So, are more cameos imminent? ‘I’m hoping for a lead role at some point – but Raine’s not putting that on the table!’ Langret says, laughing. At home in south-east London, Langret is surrounded by some of the artwork she has collected over more than two decades of working with artists. She is gearing up for her busiest week of the year – when Frieze London takes over Regent’s Park with a dazzling array of international art, from 9-13 October. There’s a big reveal for this year: a brand-new layout design for the fair. ‘It’s light and bright, with lots of windows – I can’t wait for people to come and enjoy it,’ she says.

Paris-born Langret joined the leading global art fair five years ago, but she’s an abi- ding aficionado of the art scene in the UK. ‘I think London has always been the global capital of the art world. It’s the place lots of people, including myself, have come from other places, and found communities. It makes for a really exciting art scene, and one that’s geared towards making space for new voices. That’s what I cherish.’

Among the many things Langret has achieved at Frieze London is making the fair more representative of a new generation – who face a particularly challenging time with exorbitant costs and funding cuts across the arts.

‘It’s important for me to think about who is coming up,’ she says. ‘Who may not be part of the Frieze family, and who we can include.’ The fair’s Focus section for emerging galleries is one example, where booths are available to 35 galleries at a lower price. ‘We have done quite a lot of work thinking about the processes and how to access the fair, outside of the usual ways galleries are selected,’ Langret says. Also worth a visit is the ‘Artist-to-Artist’ area, where established voices invite newcomers to present work.

Though she shrugs off the compliment, Langret is admired in the art world for her style – what will she be wearing to the fair this year? ‘I don’t know yet, but now I’m feeling the pressure!’ she says. ‘I’m going through a minimalist phase, as I don’t have much time to think about it in the morning.’ She names Jil Sander, Lemaire, Studio Nicholson, Rejina Pyo, Roksanda and Erdem as her go-to brands: ‘They all come to the fair, and I love having them around.’ Langret seamlessly creates a sense of community, bringing people from across the creative fields together in a way that feels celebratory. And London’s art scene feels richer, and all the more inclusive, for it.

Chantal Joffe

Artist

‘It’s a gift to have people sit here and try to understand who they are,’ says painter Chantal Joffe. At her fabled north London studio, housed within a Victorian warehouse overlooking the canal, she has been painting the art critic Hettie Judah, who poses in her underwear on a hot summer’s day. ‘The painting is melting off the canvas,’ Joffe says. ‘I keep saying to her, your face has gone!’ Fêted for her huge, gutsy paintings of women and children, Joffe has devoted her brush to telling complex stories for over 30 years. Her muses include her daughter, sisters and late mother Daryll; friends and acquaintances; writers and artists; and herself. In 2018, she painted a self-portrait nearly every day.

Joffe has captured so many icons and made icons of many – but shyly admits to wanting to paint Annie Ernaux and Simone Biles. In any gallery or room, Joffe’s works have an ineluctable presence; they draw you in, whispering intimacies and bristling with enigmatic energy. ‘People want to tell their story – everybody wants to talk about real stuff,’ she says. In the refuge of the studio, it’s the private, often searingly personal conversations she has with other women that shape her portraits. With another sitter, ‘life, sexuality and how we had been shaped by our parents’ divorces’ were the topics of discussion. ‘It was gripping and great; somehow the painting was amazing,’ she says. ‘I loved it. It had this intensity.’

When Joffe was still a student at Camberwell, she recalls getting red oil paint in her brown hair: ‘It took a year to wash out, but it felt like the truest thing, to become one with the paint. Like being initiated into a cult.’ Even today, when she walks into her studio, she reflects on this. ‘I love the smell of linseed oil as I’m approaching the studio door, I love how it makes me feel,’ she says.

Her unique way of seeing women – an empowered and empowering gaze on their bodies and lives, that is both fiercely honest and softly compassionate – has helped to bolster positive momentum and change. Joffe talks about the difficulties of surviving and starting out as a young woman artist in the 1990s: ‘I grew up without much, and I was used to having little. I didn’t have any big expectations. Any success was a bit of a shock!’ Now, she feels, ‘it’s the best moment it’s ever been to be a woman artist’.

Lisa Anderson

Managing Director, Black Cultural Archives

‘There is no such thing as a typical day at Black Cultural Archives,’ Lisa

Anderson says. She is managing director of the centre – ‘an extraordinary treasure trove’ of information in Brixton – whose mission is to ‘collect, preserve and celebrate the history of African and Caribbean people, to give strength and inspiration to individuals, communities and society’.

Black Cultural Archives was founded out of a commitment to reparative justice. ‘We address the pernicious effects of the falsehoods and omissions in our historical knowledge about the contributions of people of African descent in the making of Britain, let alone the wider world we live in,’ Anderson says. ‘It’s a justice issue. People’s misconceptions breed racism, which, as the race riots this August painfully demonstrated, is as present as it ever was.’

Another important part of her job is creating a space for safety, joy, freedom, empowerment and disruption. ‘We make space for new culture and knowledge, and champion academics and creatives who activate the archives,’ Anderson says. She’s especially excited about the rise of singular, home-bred talents, such as the young painters Joy Labinjo and Rachel Jones. ‘I’m also hugely inspired by emerging artists – Temitope Adebowale, Kudii, Myles Igwe, Amida Deen – and artists who throw their hands at many different things – Heather Agyepong, Harris Elliott, Ffion Campbell-Davies. We’re really spoiled for talent in the UK,’ she says.

‘God has blessed me with an amazing family and friends, as well as the instinct to never veer too far away from my passions,’ Anderson reflects, when asked how she got to where she is today. ‘I can’t imagine not being involved in the arts and culture in some way – it’s always been a through line. Even though my parents, who came to the UK as Commonwealth migrants from Jamaica, had never been to university, or heard of the subjects I chose to study, they gave me the space and means to experiment – to find my own path. And when I doubted my instincts, I was brave enough to dig into the unknown and figure out why. ’

ELLE Collective is a new community of fashion, beauty and culture lovers. For access to exclusive content, events, inspiring advice from our Editors and industry experts, as well the opportunity to meet designers, thought-leaders and stylists, become a member today HERE.