The life and art of the overlooked Surrealist trailblazer Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) is explored in an ambitious new exhibition at Newlands House Gallery in Petworth, Sussex. The show brings to the fore lesser known aspects of the artist’s work, such as later sculpture pieces.

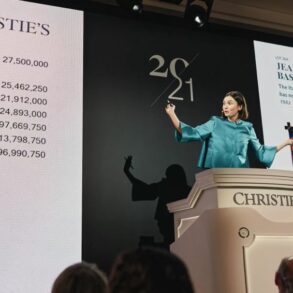

Rebel Visionary (until 26 October) capitalises on the $28.5m sale of Carrington’s work Les Distractions de Dagobert (1945), at Sotheby’s New York in May this year. The sale set the record for the most valuable British-born female at auction, leading the Wall Street Journal to ask if the art market is “ready to declare a new Frida Kahlo”.

The exhibition in Sussex is co-organised by Zurich-based Rossogranada, described as a “hybrid agency and art advisory”, and the Leonora Carrington Council. Rossogranada represents the Leonora Carrington Council in Switzerland, the UK and Europe.

The Leonora Carrington Council was founded in 2017 by Pablo Weisz Carrington, Carrington’s youngest son, and is overseen by Fermin Llamazares. Llamazares is the nephew of Edward James, the famed patron and friend of Carrington who founded the West Dean College in West Sussex. “The main purpose of the [council] is to collect, preserve, exhibit and disseminate the work of Leonora Carrington,” says an online statement.

“The exhibition includes some works that are commercially available, such as some of the sculptures, the jewellery and a selection of lithographs. The prices start from €8,200 for a 2011 lithograph, certified by both her sons, Pablo and Gabriel Weisz Carrington, going up to €180,000 for a lifecast sculpture (Butterfly Mantaray, edition of ten),” says Valeria Diaz Granada, the chief executive of rossogranada.

The show is curated by Joanna Moorhead, who went to Mexico City in search of the artist in 2006. Moorhead is a distant cousin of Carrington, and recalls that she was known in her family as Prim.

“She expected it would be a one-off visit to Mexico City to write an article for the Guardian,” an exhibition text says of Moorhead’s travels. “Instead, it became the first of many visits that would continue until Leonora’s death five years later.”

The show explores how Carrington ended up in Mexico following a tumultuous tryst with the prime Surrealist, Max Ernst. Moorhead writes: “Leonora rebelled against her parents’ ambitions in spectacular fashion when she fell in love with Max Ernst after meeting him at a dinner party [in 1937]. Ernst was 46 to her 20; German; divorced and remarried; the father of a teenage boy; and perhaps worst of all, a famous artist.”

In a photograph taken by Lee Miller in 1937, on loan from a private collection, Carrington’s breasts are cupped by Ernst’s hands. The pair relocated to the South of France in the late 1930s, but Ernst was eventually imprisoned; Carrington left for Spain, where she was subjected to degrading treatment in a psychiatric hospital. Always resourceful, she bumped into a Mexican poet in Madrid, Renato Leduc, who took her to Mexico City in 1942. She settled there until her death in 2011.

A number of the stage sets and masks, tapestries, jewellery and sculptures she created in her Mexican idyll take centre stage in the exhibition. These include the wool tapestry Beast with a Feline Head, loaned from a private collection, a set of three papier-mâché masks made for The Tempest (1958) and a wide range of later sculptures such as Feline (2010) and Carnivore (2010).

Moorhead demonstrates how Carrington tapped into contemporary issues that still preoccupy audiences today, such as her examination of how humans and animals interact, drawing on ecological concerns. The show also focuses on Carrington’s feminism, highlighting the artist’s correspondence with the New York academic Gloria Orenstein in the early 1970s.

The show features known aspects of the artist’s work, including sculpture pieces created towards the end of her life. Leonora Carrington, Bird, 2011. Bronze sculpture, 69 x 72 x 92 cm.ourtesy of the Leonora Carrington Council and rossogranad.

Moorhead says in a statement: “The themes that were important to her, as long ago as the 1940s, are the themes that are important to all of us today, especially the natural world, our place in it, and the interconnectedness of everyone and everything.”

Pablo Weisz Carrington, Leonora’s son, tells The Art Newspaper: “She believed in population control. We’re all on top of each other and fighting each other.” He adds: “I have the strong belief she is the most important British artist.”

The worst rupture came, he says, when Leonora left Europe for Mexico. “She always wanted to come back [to England], she always wanted to be back in Britain,” Weisz Carrington explains. The focus now though is on her market.

“People say she made 170 paintings or so, that is not true. She was very modest in her production,” he says. What about the record auction price achieved earlier this year for Les Distractions de Dagobert? “She would have loved to have that money.”

Drawing inspiration from the fantastical scenes depicted by Hieronymus Bosch, Carrington painted the record-breaking Les Distractions de Dagobert just three years after emigrating to Mexico–a move made by so many Surrealists fleeing the Second World War, including Remedios Varo and Alice Rahon. Two years later, the painting was included in her solo show at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York. The work was bought by the Argentine businessman Eduardo F. Costantini, the founder of the Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires, at the recent Sotheby’s auction.

Meanwhile in 2022, the curator Cecilia Alemani based the Venice Biennale around a children’s book by Carrington, The Milk of Dreams, which includes her fantastical writings and illustrations. This link to the world’s most prestigious exhibition has further boosted the artist’s critical and commercial standing.

Leonora Carrington: Rebel Visionary, Newlands House Gallery, until 26 October