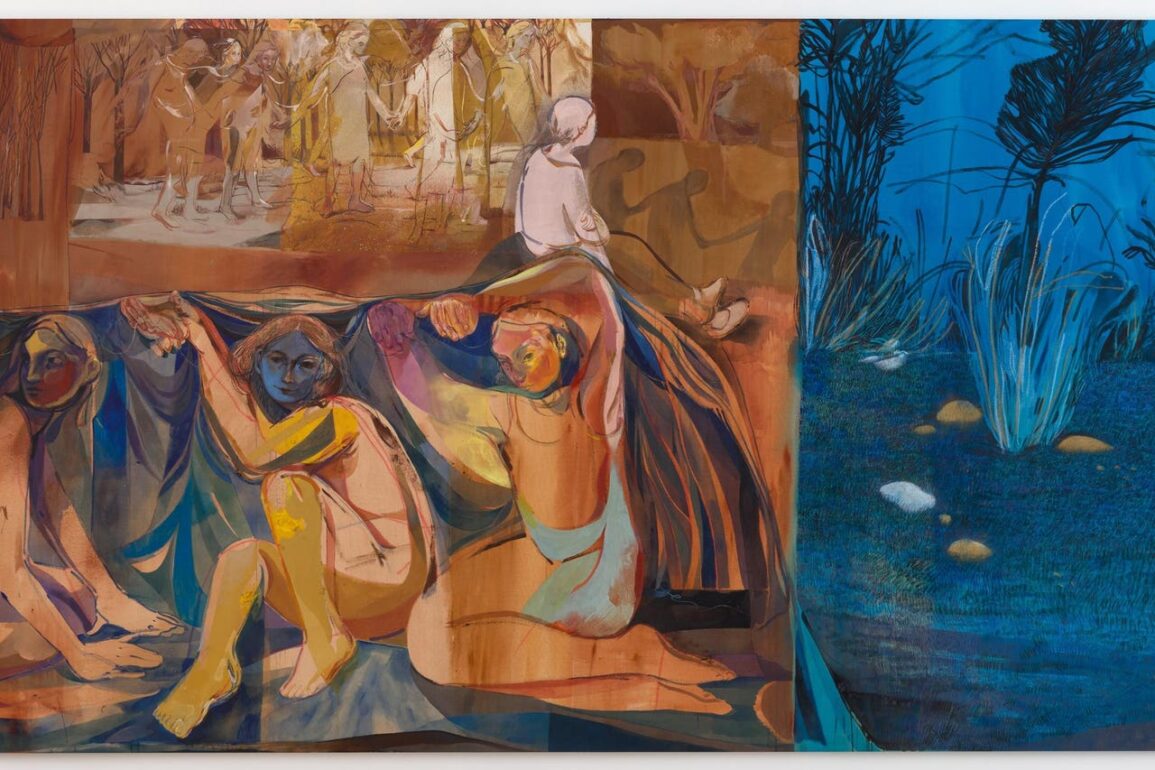

Our gaze oscillates between a lavish blue woodland scene, three children crouched under a mantle, and an adult figure above them peering into the woods, as we navigate a complex visual narrative. We stop to admire the heavy yellow brushstrokes slathered below the bent knee of the middle child, and the blue hues washed over that child’s face and within the trio’s protective cloak, drawing our eye back into the woods. The adult figures are obscured and sprinkled with glitter, creating an array of moods as we delve into their story.

Multiple geographies, influences, and techniques collide in Joana Galego’s Our Mother’s Cloak (2024), a more than 10.4-foot-wide-by-5.4-foot-high paint, glitter, glue, and soft pastel on canvas the artist created for I Was Carefree, Green and Golden, a three-woman exhibition at Isabel Sullivan Gallery in New York. The presentation, celebrating Galego (b. 1994, Portugal), Antonia Caicedo Holguín (b. 1997, Colombia), and Stephanie Monteith (b. 1973, Australia), which borrows its title from the Dylan Thomas poem Fern Hill, is on view through December 31.

The imagery for the smaller scene on the right, which compositionally creates the effect of a diptych on a single monumental canvas, first appeared to Galego in December 2021, when she was participating in an artist’s residency with the Royal Drawing School, Glasgow School of Art, and Dumfries House, a Palladian country house in Ayrshire, Scotland.

“In the cold months, it used to get dark very early, so I would take walks on the residency grounds, filled with bushes and trees, and take photographs with my phone’s flashlight. I’ve always been intrigued by the night in the woods, with its menacing yet attractive mystery. The simultaneous allure and intimidation of the unknown that lies in vast, unnamable shadows. So I started to do some watercolors based on those photographs, and eventually some paintings on found materials such as small pieces of wood,” explained Galego.

The top left portion of the canvas was inspired by Paris, Texas, a 1984 neo-Western drama road film directed by Wim Wenders. Galego participates in a drawing from a film club, where artists watch a film together, stop the screening when someone identifies a still shot, and they draw from that frame for six minutes.

“I couldn’t quite point out why I got these images together, the dark Scottish woods (which reminded me of my childhood when I used to camp with my parents in coastal and northern Portugal), and a single frame from Paris, Texas,” Galego recalled. “Probably a very simple association –- someone looking out into the unknown, introspectively, from within the safety of their home.”

To complete the narrative, Galego added three cloaked children – possibly hiding from parental supervision, playing a game, or protecting each other from the shadows outside – to juxtapose with the adult figure above staring at the blue woods.

Installation of “I Was Carefree, Green and Golden”, a three-woman exhibition at Isabel Sullivan … [+]

During a summer residency at Palazzo Monti in Brescia, Italy, Galego engaged in dialogue with Italian painters – particularly Early Renaissance master Piero della Francesca, best remembered for his serene humanism and use of geometric forms – who have influenced her since childhood, and especially since eight years ago, when she moved to London to study at the Royal Drawing School.

“I was already familiar with his (Polyptych of the Misericordia) and Madonna del Parto paintings, and this summer I dedicated more time to looking at depictions of the same themes by other artists,” said Galego. “It became clear to me that the cloak could be a symbol for protection, mercy and care.”

Stephanie Monteith Acer Silhouette 2024 Oil on linen 26 x 30 in (66.04 x 76.20 cm)

We shift our gaze to a cheerful outdoor scene, imagining what might have happened beneath the frayed striped towel draped over a pole that stands under a bare maple tree branch. We contemplate the season, with the naked tree and the verdant shrubbery growing wild rather than tamed or tormented by humans. The blue-green plant at the bottom left draws our eye back to the bright blue sky, evoking carefree joy and reminding us of the Thomas poem.

Maple trees are symbolic across cultures, with some believing they can protect people from evil spirits and danger. There is a universal sense of comfort and peculiar familiarity across Monteith’s work, where we imagine the location based on colors and natural and human made elements.

The lively colors of Monteith’s oil on linen Acer Silhouette (2024) capture a scene in her garden, embellished with imagination and creative expression.

“This acer is one of my favorite trees in my garden and it was actually covered in leaves at the time, but I decided just to focus on the textures of the bark and the way this played against the light sky at the top of the painting and a tangle of darker vegetation at the bottom,” Monteith explained. “There was also the playful addition of a beach towel and various messy dog toys hanging from the branches to add other colors to the composition.”

Antonia Caicedo Holguin My Friend Hannah Uzor – Portrait in the Studio 2024 Oil and oil pastels on … [+]

We abandon landscape to engage with Caicedo Holguin’s My Friend Hannah Uzor – Portrait in the Studio (2024), a vibrant oil and oil pastels on canvas depicting a fellow artist and her swaddled baby. We’re drawn in by the radiant red background, and the singular use of color evoking warmth and resilience. A painterly triumph of nuanced brushstrokes and shading builds depth and texture and stirs emotions. I’m reminded of what it was like to be a creative working mother when my son, now 14, was a baby, though the imagery, composition, movement, energy, and technical skill are the primary draw for a broader audience. We imagine what Uzor is thinking at the moment, balancing her emergent creative career and motherhood.

Caicedo Holguin met Uzor during their first year at the University College London (UCL) Slade School of Fine Art in 2021, where they shared a studio and “quickly became very good friends.” A year after graduation, Caicedo Holguin attended Uzor’s show at Niru Ratnam gallery in London.

“She made this show having a baby who was I think less than 1 year old. I admire her tenacity and also her strength as a woman. So I got my pastels out, and I made a pastel piece of her in her studio with her baby,” recalled Caicedo Holguin. “I loved this pastel so much that I decided to make it bigger using painting and that is the painting that is on show at Isabel Sullivan Gallery. … Originally I gave it the name Madonna, but then I realized that this painting was not about a mother and a baby, it was about a lot more.”

Installation view of “I Was Carefree, Green and Golden”, a three-woman exhibition at Isabel Sullivan … [+]

“The painting was not posed,” Caicedo Holguin continued. “Hannah just walked into her studio and sat down. I just painted what I saw. She was sitting down in her studio, her baby was wrapped around her in a fabric and you could barely see his face. Hannah looked very serene; she had her coffee mug in one hand.”

Three different women artists are in robust dialogue with each other, as Sullivan thoughtfully curated a presentation that celebrates the ferocity of women artists and their creative processes.

Explore more through these videos:

Installation view of “I Was Carefree, Green and Golden”, a three-woman exhibition at Isabel Sullivan … [+]

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content