“I come from a period where women artists had no importance,” says the Turkish artist Nil Yalter, who was born in 1938 in Cairo.

“We are more than half of the population of the earth. We have been ignored for millennia. We were just good to make children. We were cooking all the time. There were some heights for women – perhaps, from the 12th to 14th centuries – but with industrialisation, it got worse.”

For the past five decades, Yalter has fought against the exclusion of women from the art world – as she has fought for political and economic equality for nomadic communities and the poor and marginalised. Her work, steeped in politics but also in music, ritual, and history, seeks out consonances and collaborations, much as she herself does in her partnerships with poets and musicians.

This connection between sound and art is now explored by a jewel of an exhibition, The Story Behind Each Word Must Be Told, at London’s Ab-Anbar gallery. Although small, the show surveys key areas of her work with precision. It quietly highlights Yalter’s commitment to women and migrants and the sheer breadth of her influences.

“I’m humbled and honoured to curate this exhibition,” says the show’s curator, Ovul Durmusoglu, in a walk-through with the artist. “We are all feeding the core energy of this magical work that inspired me as a creator, as a human, and as a woman who grew up in Turkey.”

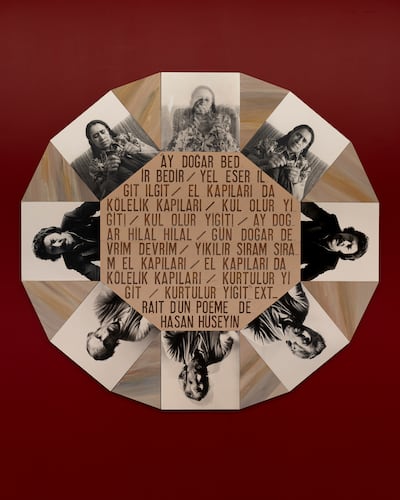

The show opens with Estranged Doors (Exile Is a Hard Job), from 1983, a wall piece that reverentially frames the titular poem, Estranged Doors, with faces of Turkish migrant workers living in Paris – many of whom were undocumented or socially invisible when Yalter made the piece. Once read aloud, the incantatory feel of the poem makes the work almost talismanic, as if it is offering protection for the people who live under precarious circumstances.

Talismans, trances, and deities are not mere metaphors here. In one of Yalter’s best-known performances, she takes on the role of a shaman, exploring the power of communication and transcendence. Ritual is also a workaday subject, attached to those who practice it. Her installation D’Apres Stimmung, which is based on Karlheinz Stockhausen’s recitation of names of polytheistic deities, shows images of these gods upon the wall – underlining the fact that these are not just abstract terms but living emblems of the world’s different belief systems.

Other works display Yalter’s famous use of symmetry, such as the video Lord Byron Meets the Shaman Woman (2009), projected on to the floor, which records her making an assured, abstract painting that Durmusoglu hung on the wall opposite. Yalter doubled the projection around a central axis, so that it looks as if two women are working, each in concert with other.

“In Islamic art and architecture, tiles, ornamentations, and walls of mosques use mirror repetition of the pattern,” she says. “But I am also inspired by immigrant workers’ carpets – those made in the villages, which is one of the main occupations for nomadic women.”

Yalter has long been inspired by the nomadic communities in East Turkey, who have pushed westward, bringing with them their living practices that are in danger of being forgotten.

“Anatolian storytelling has been a core interest in Nil’s work,” explains Durmusoglu. “Nomadic communities came from Central Asia to Anatolia. Once they had to leave Anatolia, these people moved into shantytowns in Istanbul, and then further on as immigrant workers in Germany, France, Belgium. Despite the fact that it is always said that the settlements make humanity, for me, it’s the refugees and migration that made the human societies we have.”

Durmusoglu and Yalter organised a performance during London Gallery Weekend of asik troubadour singing, which pairs Anatolian oral traditions with socialist and political sentiments. Held at a Turkish and Kurdish community centre in East London, the event welcomed 300 people – an art-world audience as well as members of the local Turkish and Kurdish communities.

Yalter recently won the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, one of the most prestigious prizes in the art world. She was honoured due to her participation in Foreigners Everywhere, the main exhibition of the Venice Biennale, where she showed two works from the 1970s: a tent installation inspired by Anatolian nomadic communities and a video of a belly dancer – that abiding cliché of Middle Eastern women.

Six decades on in her work, she says that women remain the core of her practice. She credits her mother for allowing her this focus.

“I had a very enlightened, very brilliant scholar mother,” she recalls. “When I was 15 she said to me: look, my girl. Marriage is not the most important thing for women in life. Don’t forget that. Making children is not absolutely necessary, especially for you because you have a talent. You should take your independence. I thought that it was a brilliant idea. And I adopted this philosophy.”

Updated: June 10, 2024, 3:05 AM

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content