At first glance, artists Ethel Carrick and Anne Dangar seem to have little in common, besides gender and career choice.

But a new exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) is inviting visitors to take a closer look.

The gallery’s head curator of Australian art, Dr Deborah Hart, said she thought Carrick and Dangar made a great double bill.

“They both had a strong connection with France; they both were innovators and groundbreaking artists,” Dr Hart said.

“In the case of Carrick, she brought post-impressionism to Australia [and] in the case of Dangar, she advocated for cubism.

“Carrick was a painter, Dangar was a ceramicist. So, I think for audiences, there’s a lot to see and enjoy.”

Ethel Carrick/Anne Dangar is a project five years in the making for Dr Hart and co-curator Dr Rebecca Edwards.

National Gallery of Australia’s Ethel Carrick/Anne Dangar exhibition took five years to organise. (ABC News: Emmy Groves)

“I hope what you’ll discover is two very different shows by significant women who made a great contribution to this country,” Dr Hart said.

The NGA’s Anne Dangar archives is a collection of more than 700 sketchbooks, drawings, photographs, letters, some of which feature in her half of the exhibition.

“She really is one of Australia’s most important but under-acknowledged modern artists,” Dr Edwards said.

“She formed part of a significant group of women artists in the early 20th century who were pioneering figures in modernism and household names today — like Margaret Preston, Thea Proctor, Grace Cossington- Smith, Dora Black, Grace Crowley.

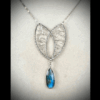

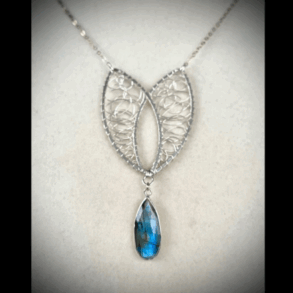

Exhibition co-curator Dr Rebecca Edwards says Dangar’s cubist pottery brings together rustic traditionalism and progressive modern art. (Supplied: National Gallery of Australia)

“[These are] figures we all know and love, but for various reasons, she’s really the last of this very pioneering group to be the subject of a major retrospective exhibition,” Dr Edwards said.

“She combined traditional regional French pottery with bold cubist designs, really bringing together kind of very rustic traditionalism with progressive modern art.

“She’s also among a very small group of Australian artists to ever form part of the European Avant Garde in the 20th century; the only to meaningfully contribute to cubism in France.”

Dr Edwards said Dangar was the first, in 1929, to teach cubist art; and arguably, to exhibit cubist art in Australia in 1937.

Dr Rebecca Edwards says Dangar is one of Australia’s most important but underacknowledged modern artists. (Supplied: National Gallery of Australia)

“Through her continued connection with artists in Australia, particularly Grace Crowley her very close friend and one time partner, [Dangar] directly influenced the development of abstraction in Sydney from the 1930s onwards,” Dr Edwards said.

Like Carrick — who Dr Hart described as known to an extent in art circles, but “very far from being a household name” — Dr Edwards said Dangar has been greatly celebrated by specialist art historians, curators, and some enthusiastic collectors.

“Through being a woman and working as a potter and being an expatriate, she’s always remained at the periphery of Australian Art History, rather than at the centre,” Dr Hart said.

“That’s certainly something we’re hoping to change with this exhibition.”

Dr Hart said the dual deep-dives means “there’s lots of [Dangar] archival material for people to enjoy, along with her works, and really tell her story in new ways” while the NGA exhibition is “by far the biggest exhibition of Ethel Carrick’s work to date” despite some primary research challenges.

Gouache (left) and Woman and Child are examples of Anne Dangar’s different artistic mediums. (Supplied: National Gallery of Australia)

“Carrick has been notoriously difficult to date [and] she gave many of her works very similar titles,” Dr Hart said.

“There was a lot of work that had to happen [and] going through resources which simply weren’t available to earlier researchers.”

Some 140 works from 65 lenders comprise the exhibition’s Carrick section, which spans the artist’s 50-year career.

It’s just her second retrospective, after the first in 1979.

“Like a lot of women, it wasn’t that she wasn’t known at the time, it’s just the way that history’s panned out that that her story deserves to be better known,” said Dr Hart.

“When Ethel Carrick went to Paris from London in 1905, it was as if windows had metaphorically flung open and she was involved in a world of new opportunity; new opportunities for women artists.

Flower market by post-impressionist painter Ethel Carrick depicts a setting in Nice, France. (Supplied: National Gallery of Australia)

“It was during this early period that she was able to discover her distinctive vision,” Dr Hart said.

“So, it was still quite rare and quite radical for women to set up outdoors [but] she really used places like the Luxembourg Gardens as an outdoor studio, and she would paint these very fresh, vibrant scenes in a post-impressionist manner.”

Dr Hart said Carrick’s painting style “might not look so radical to us today” but at the time the term post-impressionism was only just being coined, and Carrick had travelled with her husband of three years, Australian artist Emanuel Phillips Fox.

“This exhibition is an opportunity to look at [Carrick] in her own right. [She and Phillips Fox have] often been seen together, and what happens is you get this compare and contrast,” Dr Hart said.

Ethel Carrick exhibited her works, including Arab women washing clothes in a stream, under her maiden name. (Supplied: National Gallery of Australia)

“What we’re trying to do here is actually just take a very clear eyed view of what her contribution was through around 140 works. Carrick was quite independent-minded; although she signed a lot of her works ‘Carrick Fox’, she chose to exhibit under her maiden name, ‘Carrick’.

“If you go through her exhibition catalogs, the vast majority of them were ‘Ethel Carrick’, sometimes with ‘Mrs. Phillips Fox’ in brackets. So, it was a radical move.”

Dr Hart said when Carrick first visited Australia with her husband, she brought works that had been exhibited in the Royal Academy, The Salon, and other European exhibitions.

“She was one of the first post-impressionists to show and create post-impressionist works in this country, and they were seen as quite radical,” she said.

“On her second visit [to Australia], in 1913, she shows one of her famous works, Christmas Day on Manly Beach, and she really captures that sense of the light and colour of the beach in Australia. How different that would have seemed from her Christmases in the UK and in France!”

Dr Deborah Hart with The Market by Ethel Carrick, which sold for over $1 million. (ABC News: Emmy Groves)

Philips Fox died of cancer in 1915 and, for the next four years, Carrick struggled to paint.

“It’s only really in 1919 that she hits her stride again with an extraordinary painting called The Market, which sold for an extraordinary amount … over a million dollars.”

Carrick’s Balmoral Beach recently went under the hammer for $130,000 — almost 17 times what it was purchased for in 1991 — and she’s one of the few women to make the top 10 art sales of the year in Australia’s male-dominated art market.

Still, Dr Hart hopes the NGA exhibition sees Carrick appreciated and remembered for “her commitment to other women and also to social justice”, and as a “great travel artist”.

“She lived between Australia and France but travelled to France, North Africa, Spain, and Italy. Even in her 60s, she was really intrepid, and she trekked to the Himalayas in India, and she lived on a house boat in Kashmir,” she said.

“Right towards the end, she has this kind of — what her sister called ‘vim and vigour’ — this joy of life, which I think really comes through in her art.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content